What is the importance of frogs? Why are the frogs important to ecosystem, to environment? The types of frogs and their features.

Importance of frogs; Frogs consume enormous numbers of insects. This makes them valuable to many agricultural industries, where they destroy pests and save millions of dollars each year. Frogs also provide food for many other animals, including man. The legs of some large frogs are regarded as delicacies.

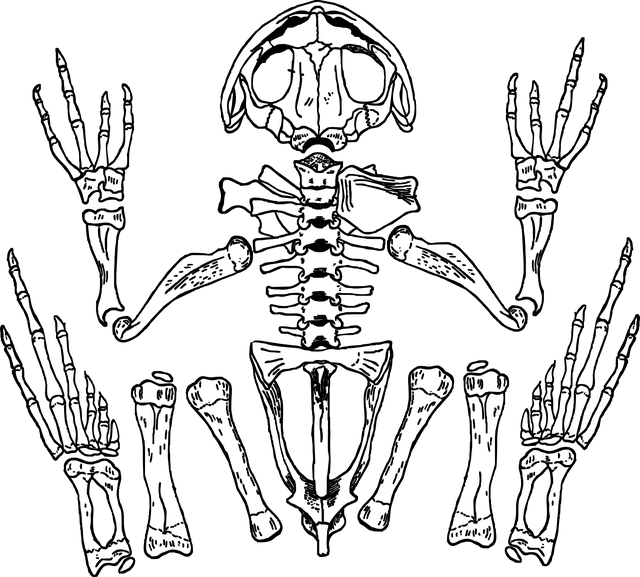

Frogs and toads also are important laboratory animals. Frog eggs are frequently used to study the details of embryonic development. Adult frogs are used to study vertebrate anatomy and physiology. Tadpoles are used to study the phenomenon of regeneration. Frogs may also be used to test for pregnancy. The urine of a pregnant woman injected into a mature female frog causes it to ovulate within a few hours.

Source: pixabay.com

TYPES OF FROGS

The order Anura—frogs and toads—is divided into 14 families. Members of one family of frogs—the family Leiopelmidae, or Ascaphidae— are in effect “living fossils.” There are now only three species in New Zealand and one in North America representing what was once a cosmopolitan group that first appeared in the fossil record some 150 million years ago. The four living species retain the tail-wagging muscles, even though tiiey, like other frogs, have no tails to wag. A somewhat similar archaic group is the family Discoglossidae, which is widely dispersed in Eurasia, with one species in the Philippines. Included in this family are the aquatic fire-bellied toads.

Another very ancient group is the aquatic family Pipidae. This includes the bizarre Surinam toad of South America (Pipa) and a number of water frogs in Africa, such as the South African clawed toad (Xenopus laevis), once used for pregnancy tests and now a donor of eggs for the study of embryonic development. Probably closely related is the Central American family, Rhinophrynidae, which includes only one species, a terrestrial burrower.

The family Pelobatidae is almost worldwide and includes many digging and burrowing forms adapted to life in arid regions. Some of these have horny projections on the sides of their feet that serve as digging spades. This family is also very ancient, appearing in the fossil record about 120 million years ago.

The family Hylidae includes the most common tree frogs of all regions of the world except Africa and tropical Asia. Most of them have expanded finger and toe tips, a useful adaptation for climbing. They can even negotiate vertical glass surfaces.

Source: pixabay.com

The Bufonidae are the “toads.” One, the giant marine toad (Bufo marinus), has been introduced by man in most tropical countries in order to feed on insects injurious to crops such as sugarcane. Closely related are the Leptodactylidae, a large and varied family with almost worldwide distribution. Also closely related are the tiny, sluggish, brilliantly colored, emaciated-looking Atelopodi-dae of Latin America, which have skin glands that secrete a powerful poison. A somewhat similar family of brightly colored frogs is tire Dendro-batidae, or arrow poison frogs, of Central and South America.

The family Ranidae includes the common spotted or green frogs, along with a number of less familiar tropical forms, and is found on all continents except Australia. A European frog, Rana temporaria, and the leopard frog (Rana pipiens) of North America continue to be important sources of eggs for embryonic studies. The latter is used for one kind of pregnancy test. The North American bullfrog, Rana catesbiana, is widely used as a laboratory subject in introductory anatomy courses and is also raised for food.

Closely related to the Ranidae are the Rhacophoridae, a family of tree frogs found in Africa and tropical Asia. They have adhesive disks at the tips of their fingers and toes.

The narrow-mouthed toads of the family Mi-crohylidae, or Brevicipitidae, are distributed worldwide- with the exception of Australia. They are inconspicuous rotund little frogs that are mostly nocturnal and capable of digging into loose soil. Some are entirely terrestrial. The tadpole has a unique construction. The Phrynomeridae are a small group of African frogs apparently related to the Microhylidae.

ECOLOGY

Frogs are an important part of the ecology of any region they inhabit. Most have two distinct roles in the economy of nature—one as tadpoles and one as adults. Adults occupy a number of different ecological niches to which they have become specifically adapted.

Place in the Food Web.

Most tadpoles are primary consumers—that is, herbivorous, feeding on plants—and are themselves an important source of food for aquatic secondary consumers—predators and carnivores, primarily fishes and certain aquatic insects.

Adult frogs, on the other hand, are secondary and tertiary consumers, feeding on a variety of invertebrates. They are not at all fussy about what they eat. It seems that a frog will try to eat any small moving thing that comes near it. Some frogs feed on other frogs, and others (genus Xenopus) even regularly eat some of their own tadpoles.

The primary importance of frogs to man lies in the vast numbers of insects they devour each year. This is especially important in the tropics. Adult frogs are themselves important sources of food for many other tertiary consumers, including some birds (such as herons), mammals, and reptiles, particularly snakes.

Major Adaptive Types of Frogs.

There is no terrestrial environment in which frogs are not important members of the ecological community, and they are dominant members of many tropical ecosystems. Even deserts and boreal regions have at least a few species of frogs. Only the most remote oceanic islands have not been colonized by some frog species. For purposes of description, adult frogs may be grouped in four major adaptive types, occupying four major adaptive zones.

Source : pixabay.com

Aquatic Frogs.

Aquatic frogs are most common in the tropics but are also found in temperate regions in the Southern Hemisphere. They are an ancient type of frog, appearing very early in the fossil record. Fully aquatic frogs that evolved very early include pipids and some discoglossids. Other families have produced fully aquatic frogs as secondary adaptations—for example, the ranids and leptodactylids.

Terrestrial Frogs.

Another major adaptive type is the terrestrial frog. Some terrestrial frogs are semiaquatic. These are the most successful of all frogs, being found from latitudes around Alaska and Sweden to the southern tips of the continents of the Southern Hemisphere. In this group are included typical riparian and grass frogs, wood frogs, toads, and toadlets.

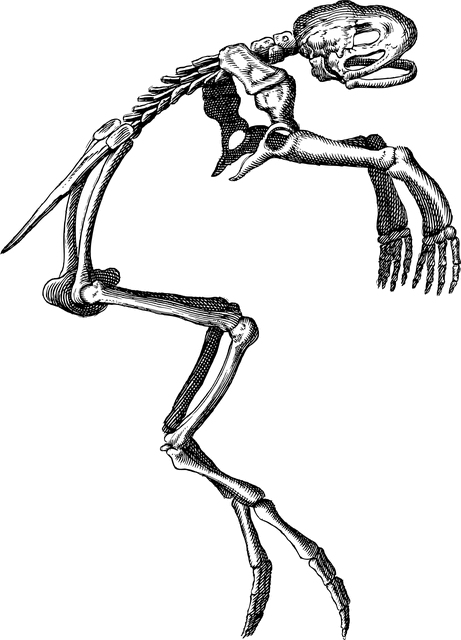

Of all frogs, terrestrial frogs are the most active and alert. Many of them are extremely agile jumpers but others are relatively slow and walk rather than jump. Terrestrial frogs frequently produce noxious skin secretions. All are important insect eaters.

Arboreal.

A third major adaptive type is the arboreal (tree) frog. Tree frogs are most common in tropical regions, decreasing in numbers rapidly in colder climates.

Tree frogs are usually smallish, although body lengths of 4 to 5 inches (10-12.5 cm) are known. They are comparatively sluggish and crawl about slowly, often showing no fear while being handled. They seem to rely mostly on cryptic coloration for protection and so have lost the fear reactions so apparent in terrestrial and aquatic frogs. Some, like terrestrial frogs, produce noxious skin secretions.

Tree frogs cling tenaciously to whatever they come in contact with, even a hand. If a tree frog falls out of a tree or misses its landing in a jump from one limb to another, it will spread its limbs rigidly, thus increasing its surface area and thereby tending to break its fall. Similar adaptive behavior is also found in tree-living lizards and mammals. In contrast, a terrestrial frog dropped from a high place wiggles and squirms in panic and consequently falls like a rock.

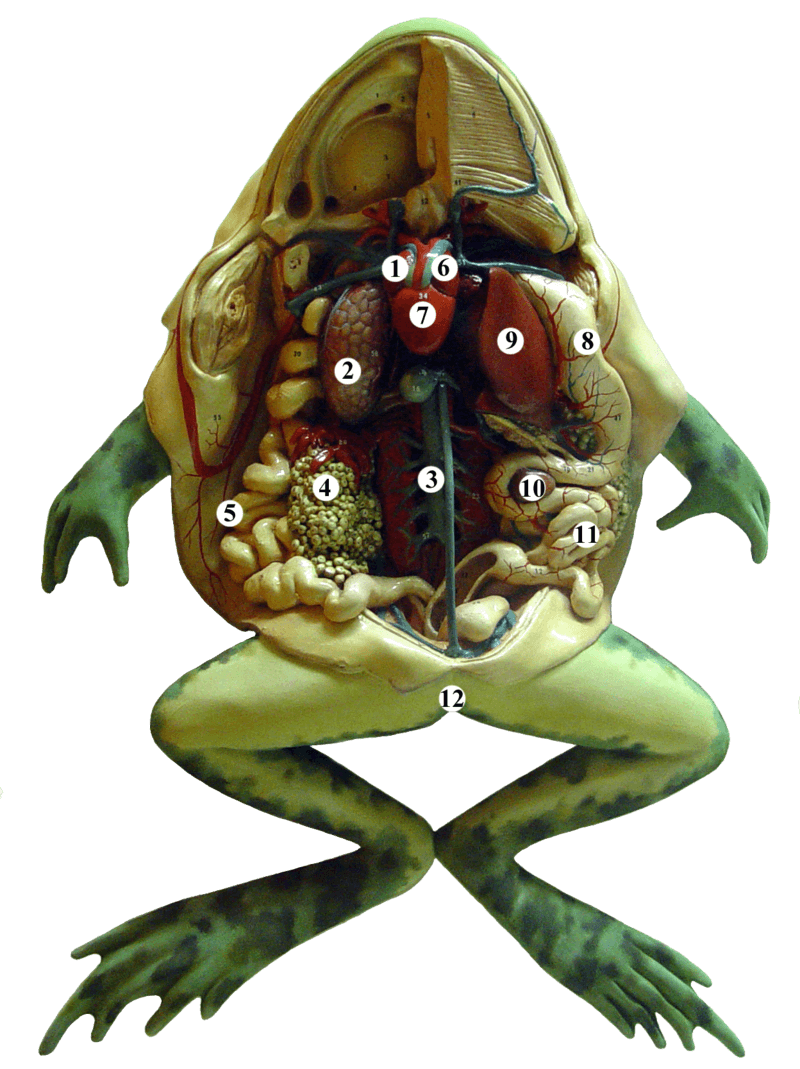

Anatomical model of a dissected frog: 1 Right atrium, 2 Lungs, 3 Aorta, 4 Egg mass, 5 Colon, 6 Left atrium, 7 Ventricle, 8 Stomach, 9 Liver, 10 Gallbladder, 11 Small intestine, 12 Cloaca (Source : wikipedia.org)

Burrowing.

The fourth major adaptive type of frog is the fossorial (burrowing) frog. Many of these frogs have a digging tool composed of hardened skin, forming a metatarsal tubercle on a side of the foot—the “spade” of spadefoot toads. Using this spade, burrowing frogs dig into the ground backward. Some do not burrow very deeply but form shallow shelters from .which they emerge at night or on damp days. Some may burrow rather deeply during dry seasons in arid and semiarid regions.