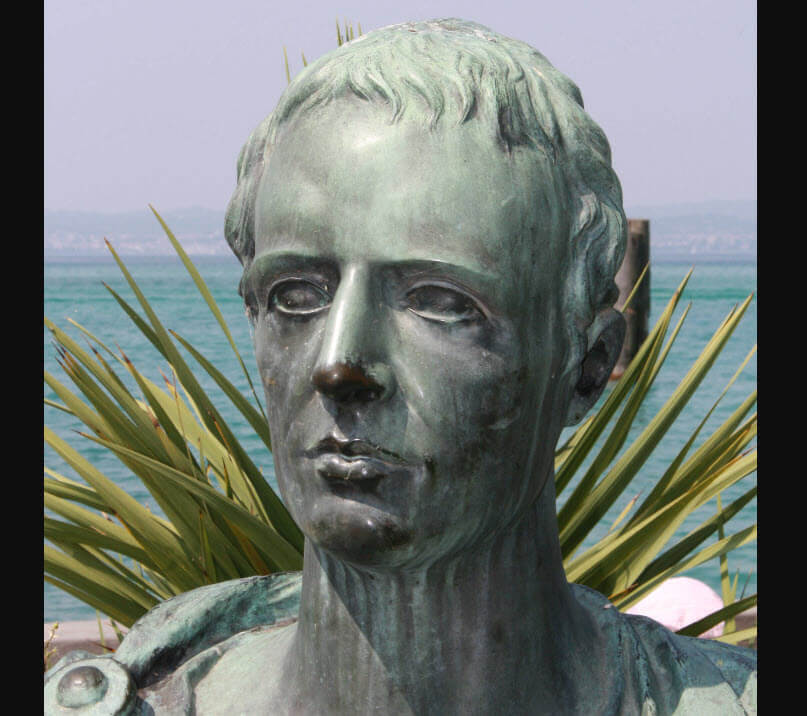

Who was Gaius Valerius Catullus? Information on Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus biography, life story, works and poems.

Source: wikipedia.org

Gaius Valerius Catullus; (c.84-c. 54 b.c.), Roman poet, whose love lyrics served as models for later European poets. There is little certain knowledge of his life. According to ancient sources, he was born in 87 b.c. and died at the age of 30; one datum or the other must be in error, since there are clear references in his poems to events after 57 b.c. However, since his 116 extant poems—most of them short, a few of them fragmentary—tend to be self-revealing to an extent unusual in world literature, a fairly plausible biography can be constructed mainly on their evidence.

First Poems.

A native of Verona, Catullus went to Rome, apparently in his early 20’s. During his first years there he shared the more or less Bohemian life of a group known as the “New Poets,” who were attempting to introduce into Latin the meters and poetical techniques of the Greek lyric and short epic, especially those characteristic of the Alexandrian age. To this period may belong such poems as the Hymn to Diana (No. 34) and the marriage songs, or epithalamia (Nos. 61 and 62). Catullus’ success in the adopted forms probably contributed to his being called doctus, which means not only “learned” but also “skillful, technically adept.”

Love Poems.

In the late 60’s b. c., Catullus fell passionately in love with an older woman. Called “Lesbia” in his poems, she is almost universally identified as Clodia Pulchra, wife of the consul Metellus Celer and sister of Clodius Pulcher, one of Cicero’s bitterest political enemies. Clodia’s family was aristocratic, ruthless, and dissolute, and Catullus’ relationship with her was probably brief and undoubtedly disastrous. The first poem he wrote to her, “He who sits near you seems the equal of a god” (No. 51), is a translation from Sappho of Lesbos and may have suggested the pseudonym Lesbia. At its most passionate the affair produced such pieces as “Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love” (No. 5), “How many kisses are enough?” (No. 7), and the songs on his lady’s pet sparrow and its death (Nos. 2 and 3).

These poems were followed by a long series of lyrics containing scabrous attacks on the poet’s more favored rivals in love and voicing his own doubt and torment. Typical of these are “Miserable Catullus, stop playing the fool” (No. 8); “I hate and love. If you ask me why,/ I have no answer, but I feel it to be so and I am in agony” (No. 85); and the meditative, prayerful “O gods, if it be yours to pity, deliver me from this love, this plague, this ruin, this foul disease” (No. 76). Revulsion fills what is presumably one of Catullus’ last comments on his grand passion: “O Caelius, our Lesbia, that Lesbia,/ That Lesbia, she whom Catullus only/ Loved, more than he loved self or any other,/ Now in the gutters and the darkened byways/ Rolls with the random sons of Father Remus” (No. 58). Similarly, disgust is voiced in his message of farewell, in which the poet wishes Clodia good luck with her lovers, “three hundred of whom she clasps in one embrace, loving none sincerely, but draining them all over and over” (No. 11).

Later Poems.

About 57 b. c., perhaps to escape from the scene of so much personal suffering, Catullus went to the Roman province of Bithynia in Asia Minor as a member of the governor’s staff. His stay in Bithynia, while disappointing financially, was poetically productive. Visiting»his brother’s grave near the site of Troy, he composed the famous Ave atque vale (Hail and Farewell!, No. 101). He also became acquainted with the orgiastic cult of the Asiatic Great Mother and composed Attis (No. 63), a long poem in hectic rhythm telling how a Greek youth, carried away by divine frenzy, castrates himself in the goddess’ honor and disappears forever into the forest.

Catullus must have returned to Rome in time for the trial, early in 56 b. c., of his friend and rival in love, Marcus Caelius Rufus (doubtless the “Caelius” mentioned in No. 58). Caelius, accused by Clodia of trying to poison her, was defended by Cicero. Cicero‘s defense speech, still extant, apparently resulted in Caelius’ acquittal and the total ruin of Clodia’s reputation. It may have been on this occasion that Catullus expressed his approval of Cicero in the poem beginning “Most eloquent of Romulus’ grandsons” (No. 49).

Probably during the very last years of Catullus’ life he wrote a series of epigrammatic poems attacking Julius Caesar and his political henchmen. At some point, however, Catullus apologized and was invited to dinner by Caesar. Also from this period are the rather stilted translation of Callimachus’ lost poem, Berenices Hair (No.66), and the longest of Catullus’ extant poems, The Marriage of Peleus and Thetis. This epyllion, or small-scale epic is chiefly notable for the extensive description of Theseus’ desertion of Ariadne, a scene that forms part of the decoration of Peleus and Thetis’ marriage bed. Lastly, there are a number of vehement attacks on miscellaneous individuals. These poems contain much obscenity and scatology; their interest lies not in their content but in the skill with which the poet poured unpromising material into a delicate poetic mold.

Style and Influence.

Catullus used various metrical forms, and his extant poems are arranged according to meter. His characteristic meter, however, is the hendecasyllabic, or 11-syllable, line. (An example of this meter in English is Tennyson’s “Here I come to the test, a tiny poem/ All composed in the meter of Catullus.”) He also was fond of the elegiac couplet and had much influence on such later elegists as Ovid and Propertius.

Catullus’ reputation in later antiquity was minor but secure. During the Middle Ages, however, even in the period of courtly love poetry, when Ovid was the “master of the art of loving,” Catullus was almost completely ignored. His poetry was preserved in only one late medieval copy, except for which his work would probably have been lost forever.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the revival of learning saw a revival of interest in Catullus. He became a model for love poets writing both in Renaissance Latin and in the vernacular languages. His epithalamia (which had been the forerunners of others written in Latin) were the models for the marriage songs of the English poets Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, and Robert Herrick.

Interest in Gatullus intensified in the 19th century, when some critics ranked him among the few greatest lyricists of all time because of his emotional vehemence, sincerity, and lack of restraint. It should be noted, however, that his occasional touches of self-mockery, his concern with form and erudition, and his predilection for the less pleasant aspects of life are far removed from 19th century romantic idealism.

mavi