Who was Kazimir Malevich? Explore the life, nationality debate, and artistic legacy of Kazimir Malevich, the Russian painter known for introducing suprematism. Discover his impact on the art world, from groundbreaking exhibitions to his influence on postwar artists and his presence in popular culture.

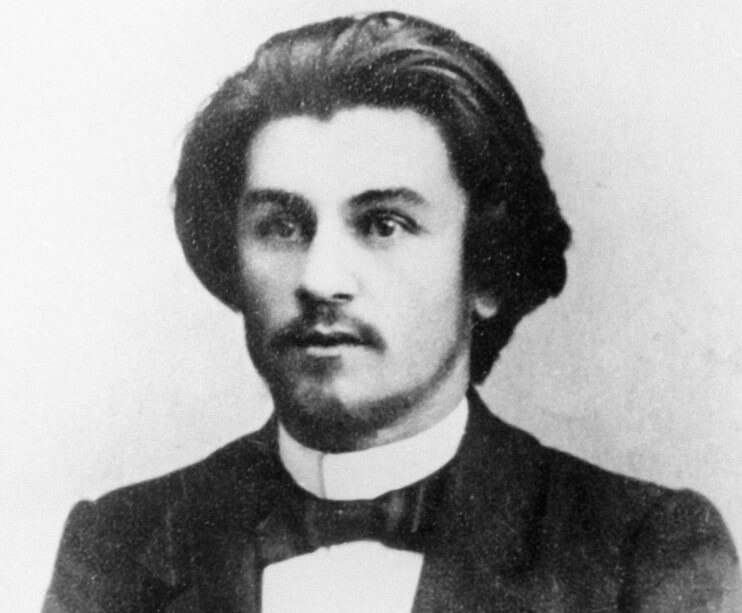

Kazimir Malevich; (1878-1935), Russian painter, who introduced a style of geometric abstractionism called “suprematism.” He was born in Kiev on Feb. 11, 1878. While studying in Moscow, he became familiar with French postimpressionist works and about 1908 began to paint in a postimpressionist manner. Soon afterward he exhibited cubist pictures with the Jack of Diamonds group, founded in 1910 by the Russian painter M. K. Larionov. By 1911, Malevich was painting in a manner strongly resembling the somewhat later machine cubism of Fernand Léger.

Malevich continued to explore aspects of abstraction in an attempt, as he said, “to free art from the burden of the object.” In 1913 he exhibited a picture entitled Basic Suprematist Element (Leningrad, State Russian Museum). This pencil drawing of a black square on a white ground carried abstraction to an ultimate geometric simplification. It was the first example of the style to which he gave the name suprematism. In a manifesto published in 1915, he explained that the main elements of this style were the square, circle, and rectangle and that the “pure emotion” produced by the combination of geometrical shapes was for him the “supreme essence” of painting. He produced a number of suprematist compositions with variations of these shapes in clear colors on white backgrounds. About 1918 he reached an extreme of nonobjectivity when he painted Suprematist Composition: White on White (New York City, Museum of Modern Art)—a tilted white square within the canvas square of a different value of white. He died in Leningrad in 1935.

Nationality and Ethnicity

Kazimir Malevich, the renowned artist associated with the Russian avant-garde, has had his nationality and ethnicity debated by scholars and cultural institutions. Born to ethnic Polish parents within the Russian Empire, Malevich had connections to both Polish and Russian cultures, reflected in his use of both languages and his signature in Polish. Despite this, his nationality remains contentious, with claims of Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian affiliations.

In 1926, Malevich himself claimed Polish nationality in a visa application, but later documents suggest he may have identified as Ukrainian, perhaps to avoid anti-Polish discrimination under Soviet rule. This complexity has led to ongoing discussions among scholars and institutions, especially amidst political and cultural pressures, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Recent actions by museums, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Stedelijk Museum, to label Malevich as Ukrainian have sparked controversy, with Russia objecting to the change. However, the consensus among art historians, including those of Ukrainian origin, is that the question of Malevich’s identity remains unresolved, emphasizing the need for further dialogue and examination of his background and affiliations, particularly in the context of Russian colonialism.

Legacy

Malevich’s artistic legacy spans continents and generations, leaving an indelible mark on the art world. His influence reached its pinnacle with the inclusion of his works in Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s groundbreaking exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1936. This exhibition, followed by the establishment of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in 1939 by Solomon R. Guggenheim, a fervent collector of the Russian avant-garde, solidified Malevich’s position as a central figure in the realm of abstract art.

The first U.S. retrospective of Malevich’s work in 1973 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum sparked widespread interest, further amplifying his influence on postwar American and European artists. However, access to Malevich’s oeuvre and the broader story of the Russian avant-garde remained limited until the era of Glasnost. In 1989, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam hosted the first large-scale Malevich retrospective in the West, showcasing paintings from their collection and pieces from the collection of Russian art critic Nikolai Khardzhiev.

Malevich’s artworks are now housed in prestigious art museums worldwide, including the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, which boasts the largest collection of Malevich paintings outside of Russia. Notably, the State Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki also holds a significant collection of his works.

Malevich’s impact extends beyond the realm of art museums, reaching the art market with remarkable sales of his iconic pieces. The discovery of the fourth version of his renowned “Black Square” in 1993 in Samara, subsequently acquired by the State Hermitage Museum, marked a significant event in the art world. Notably, in 2008, the Stedelijk Museum restituted five works to Malevich’s heirs, setting a world record for the sale of any Russian work of art in 2008 with the auction of “Suprematist Composition from 1916” at Sotheby’s in New York.

In popular culture, Malevich’s life and works serve as inspiration for various artistic endeavors and literary works. References to Malevich abound in literature, with novels such as Martin Cruz Smith’s “Red Square” and Noah Charney’s “The Art Thief” exploring themes of art theft and the significance of Malevich’s compositions. Additionally, British artist Keith Coventry and filmmaker Lars von Trier incorporate Malevich’s art into their respective works, using it as a commentary on modernism and as visual motifs in cinematic productions like “Melancholia” and cultural events such as the Closing Ceremony of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, where Malevich’s themes were projected, showcasing his enduring influence on 20th-century Russian modern art.