What is Marxism? What are the features of Marxism? Development of Marxist Theory, Information on Marx’s social theory, economic theory.

MARXISM is a political and social doctrine developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and officially maintained by the Communist parties.

Essential Features:

Marxism is a theory of the nature of history and politics as well as a prescription for revolutionary action to bring the industrial working class to power and create a classless society. The basic propositions of Marxism are that the economic forces of production determine the basic form of the class structure, the state, and the religious and intellectual superstructure of society; that society has been dominated by a ruling class of property owners who exploit the lower class; and that according to the laws of the “dialectic,” each social system generates the forces that will destroy it and create a new system, with political revolution and the emergence of a new ruling class mark ing each transition.

Karl Marx

According to Marxism, mankind has experienced five types of society—primitive communism, Asiatic society, ancient slave-holding society, feudalism, and capitalism; The expected breakdown of capitalism will set the stage for a proletarian revolution and the establishment of a classless communist society with the “withering-away” of the state.

Different schools of Marxism—revisionist (moderate), orthodox, and revolutionary (Bolshevik, Communist)—have differed mainly over questions of methods : democratic or violent, gradual or abrupt. Wherever Communist parties have come to power, Marxism has been made the official philosophy, but its interpretation has been controlled by each Communist government to justify its own policies. The Marxist prophecies of the classless society and the withering-away of the state have not come true ; instead, the characteristic pattern of the officially Marxist societies is a bureaucratic dictatorship.

Development of Marxist Theory:

The theory of Marxism was worked out by Marx and Engels over an extended period of time in the 19th century, and the different stages of their thought show different emphases and even contradictions. By 1845, when he was 27, Marx had assimilated the three main intellectual sources of his theory—German philosophy (Hegel), French Utopian socialism, and British classical economic theory. In his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, Marx concluded that man was alienated from his own true nature by the class system and the exploitation of the lower class by “the upper. In 1845, in The German Ideology, he formulated his materialist conception of history, and in 1847, in The Poverty of philosophy, he produced his first systematic statement of the dialectical breakdown of capitalism and the predicted triumph of the proletarian révolution.

Beginning with the publication of their fiery summation, the Communist Manifesto, in January 1848, Marx and Engels devoted the next five years to revolutionary political agitation and to journalistic comments on Europe’s unsuccessful revolutions of 1848-1849. From 1852 until the mid-1860’s, Marx concentrated on the scholarly elaboration of his economic theory of capitalism, publishing his Critique of Political Economy in 1859 and the first volume of Das Kapital (Capital) in 1867. In 1864, with the organization of the International Workingmen’s Association, Marx renewed his interest in practical political activity. Much of his writing from that time, until illness (and possibly self-doubt) sapped his powers in the mid-1870’s, was devoted to discussing programs, especially in The Civil War in France (1871), on the meaning of the Paris Commune, and The Critique of the Gotha Program (1875), on the future communist society.

After 1875 most of the development of Marxism was the work of Engels, who extended it with writings on philosophy (Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science, or “Anti-Dühring,” in 1878, and The Dialectics of Nature, not published until 1925) ; on sociology (The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, 1884) ; and on the theory of history (mainly in letters).

Karl Marx and Lenin

Marx’s Social Theory:

Marx’s theory of society, termed by Engels “historical materialism,” attributes fundamental importance to the economic aspect of life. According to Marx, the technological conditions of producing and exchanging goods (the “forces of production”), together with the system of property ownership (the “relations of production”), determine the basic division of society into two classes and the fundamental nature of government, religion, and culture in any given society. Marxism is thus a form of economic determinism, in which the economic circumstances are regarded as the “base” of the social system, and the political, legal, and religious institutions are the “superstructure,” whose nature is substantially governed by the form of the base.

Together with its superstructure each society develops an “ideology,” a set of official beliefs or religious doctrines justifying the power of the ruling class. Marx once defined ideology as “false consciousness,” in other words a view of the world distorted by the class interests of the exploiters and upheld in order to justify those interests.

Historically, after the hypothetical epoch of primitive communism, all societies, according to Marxism, have been based on a division into two classes, the property-owning exploiters and the propertyless class of exploited workers. Social change from one system to another comes about primarily from changes in the economic base, giving rise to a new ruling class that takes political power through revolution and causes its new ideology to prevail.

The identity of each ruling class and its respective lower class depends on the state of development of the economic base. Ancient slave-holding society, based on crude agriculture, was divided into the slaves who toiled and the owners who exploited them ; the superstructure was the city-state or the ancient empire, and the ideology “was the pantheon of Greco-Roman religion. The concept of Asiatic society was not clearly developed by Marx and Engels, but it was intended to recognize an alternative to the slave-owning society, where the exploiters were the class of government officials who extracted taxes from the peasants. Presumably more progressive was the society of feudalism, although it is hard to find a significantly different economic base for it. In feudal society the ruling class was the nobility, which exploited the serfs ; the superstructure was the monarchy ; and the ideology was the Christian religion.

Tn elaborating his philosophy of history Marx devoted most of his attention to the transition from feudalism to capitalism (especially in England) and the rise of a new ruling class, the bourgeoisie, deriving its power from the accumulation of monetary capital and the modern technology of industrial production. He analyzed the commercial development of the 17th century and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th as the stage of the “primary accumulation of capital” and attributed the English Revolution of 1642 and the French Revolution of 1789 to the drive of the rising bourgeoisie to achieve political power. “Laissez-faire” liberalism, with parliamentary government that denied the vote to the workers and kept hands off business, represented to Marx the ideology and the superstructure characteristic of the capitalist society.

Following the same pattern, Marx predicted revolution by the class of industrial workers who were exploited by the capitalists. He prophesied that the workers would overthrow and expropriate the owners of capital and establish a classless society of socialism or communism (Marx used the terms almost interchangeably).

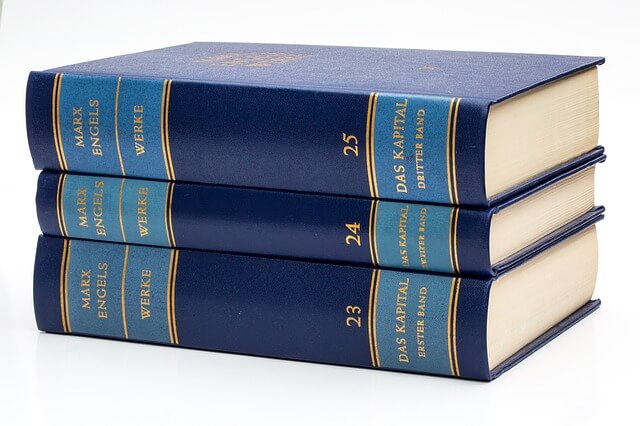

Das Kapital

In some of his historical writings, Marx qualified his economic determinism and conceded the role of force and political action in history. Engels in his late letters made a general acknowledgment of the possible reverse influence of the political and ideological superstructure of society on the economic base. In the “last analysis,” however, economic developments were the decisive factor both in generating change and in limiting human aspirations at any stage.

Marxian Philosophy—The “Dialectic.”

Marx’s philosophy as a whole has been termed “dialectical materialism” by his followers. It is “dialectical” because it takes Hegel’s philosophy of the “dialectic” (from the Greek, meaning an argument) as its model of the process of change both in society and in the world of nature; there, a given situation (the “thesis”) generates opposing forces (the “antithesis”) that ultimately break up the original situation and produce a new one (the “synthesis”). The synthesis then becomes the “thesis” for the next stage of development.

The Marxian theory of society follows the dialectical model closely. Social change is prompted by the development of “contradictions” between the class system and the political superstructure on the one hand and new developments in the economic base on the other. (Where such innovation originates is never clearly explained.) Quantitative social changes are suddenly transformed into qualitative changes when the tension between “thesis” and “antithesis” erupts in revolution. In the dialectical view, social change is usually abrupt and violent, and revolution is therefore the norm.

The Marxian dialectic is “materialist” because, contrary to Hegel, it deals not with the world of ideas as the primary reality, but with the material world. Marxism is materialist in two senses: first, in rejecting any religious or metaphysically “idealist” view of the universe and, second, in asserting the primacy of material (economic) factors rather than ideas in human history. Marxism does not hold that individuals are guided only by economic self-interest, nor does it extend to the ethical materialism of extolling such motives. In fact, Marxism represents an impassioned moral protest against the rule of self-interest in human affairs. The ethical appeal of Marxism as a creed of equality and fraternity has been a major factor in its political success.

Marx had no particular scientific reason for carrying over his philosophic dialectic into his description of society; it was merely his crude way of trying to represent social problems in a dynamic developmental manner. Some Marxists, following Engels, have attempted to apply the dialectic to the physical and biological worlds. There is even less scientific merit in that.

Marx’s Economic Theory:

The Marxian theory of economics is primarily an analysis of capitalism, with England in Marx’s own time as the model. Marx made a combined moral and economic attack on capitalism with his theory of exploitation and surplus value, and he argued, in the pattern of the dialectic, that the inherent contradictions in capitalism would ultimately destroy it.

Capitalism, according to Marx, is based on the exploitation of the working class (proletariat) by the owners of capital (factories, machinery, and working capital), whose profits come from the difference between the wages of labor and the value of the product. Marx borrowed most of his argument from the British classical economists Adam Smith, Thomas Mal-thus, and David Ricardo, although they wrote in defense of capitalism. He followed them on the labor theory of value, the iron law of wages, and the concept of surplus value. According to the labor theory of value (which neglects the modern attention to utility or demand), the value of a commodity is determined by the labor necessary to produce it. Wages, however, according to the iron law, are pushed down to the subsistence level by increasing population and held there by the “reserve army” of the unemployed. The difference between the wage level and the value of the product is “surplus value,” which is appropriated by the capitalist as profit.

Karl Marx

Besides his moral condemnation of surplus value of exploitation, Marx added three propositions about the development of capitalism: the law of accumulation, by which, he argued, competition forced capitalists to reinvest their profits in order to cut labor costs and increase production ; the law of concentration of capital, by which big capitalist grew bigger by forcing the smaller ones out of business and into the working class; and the law of increasing misery of the proletariat, by which labor-saving machinery increased the ranks of the unemployed and thereby depressed wages.

In the later volumes of Capital, unpublished until his death, Marx tried to argue that the rate of profit on capital must necessarily fall as industry expands, thus contributing to the business cycle and the ultimate crisis of capitalism. Ultimately, Marx believed, capitalism would be paralyzed by the contradiction between the social nature of industry and the system of evermore concentrated private property. Capitalism would exhaust its possibilities of development and give way in the next stage of the dialectic to the proletarian revolution and socialism.