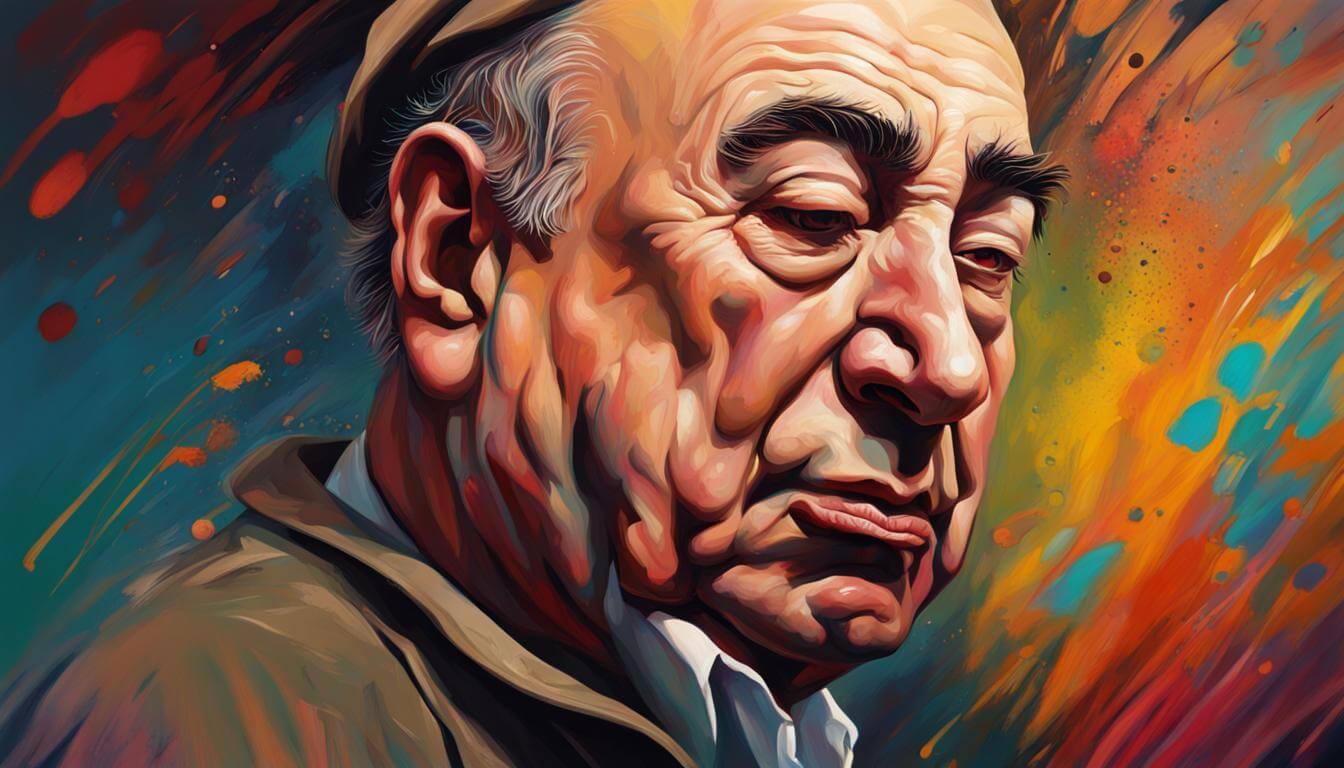

Explore the life, love poetry, and political journey of Pablo Neruda, the iconic Chilean poet. From his early years to Nobel recognition, discover the enduring impact of his diverse works, including love verses and politically charged epics. Uncover the controversies surrounding his final days and delve into the intricate legacy of this 20th-century literary giant.

Pablo Neruda, born on July 12, 1904, in Parral, Chile, and passing away on September 23, 1973, in Santiago, was a prominent Chilean poet, diplomat, and politician, honored with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971. Widely regarded as the most significant Latin American poet of the 20th century, Neruda’s literary journey began in his early years.

Early life and love poetry

Born to José del Carmen Reyes and Rosa Basoalto, Neruda’s mother passed away shortly after his birth. Raised in Temuco, Chile, by his father and stepmother, he exhibited an early aptitude for poetry, starting to write at the age of 10. Facing parental disapproval, Neruda adopted the pseudonym Pablo Neruda, a name he formally adopted in 1946. His education at the Temuco Boys’ School, where he finished in 1920, was complemented by the influence of Gabriela Mistral, a renowned poet and his school principal.

Neruda’s literary career initiated with contributions to local newspapers and later to Santiago-based magazines. Moving to Santiago in 1921 to pursue French studies and become a teacher, he faced adversity, leading to a bohemian lifestyle. His first poetry collection, “Crepusculario,” was published in 1923, marked by subtlety and elegance in the tradition of Symbolist poetry. “Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada” (1924), inspired by a tumultuous love affair, became a sensation, showcasing his poignant and original expressions of youthful passion.

Despite early success, financial instability led Neruda to pursue diplomatic appointments. He served as an honorary consul in Rangoon, Colombo, and Batavia, experiencing poverty and loneliness. During his Asian sojourn, he penned “Residencia en la tierra, 1925–1931” (1933), moving away from conventional lyricism to a personalized technique marked by surrealistic elements. These cryptic and unsettling poems depicted a descent into chaos and decay, reflecting personal and collective anguish.

Returning to Chile in 1932, Neruda struggled to sustain himself through poetry. His appointment as Chilean consul in Buenos Aires in 1933 brought him into contact with the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, forging a lasting friendship and mutual admiration. Neruda’s diplomatic career and poetic endeavors remained intertwined, contributing to his multifaceted legacy in literature and international affairs.

Communism and poetry

In 1934, Pablo Neruda assumed the role of consul in Barcelona, Spain, and subsequently transferred to the consulate in Madrid. His rapid ascent in Spanish diplomatic circles was facilitated by the introduction of Federico García Lorca, an esteemed Spanish poet. Immersed in a circle of politically engaged individuals, including Rafael Alberti and Miguel Hernández, who were affiliated with radical politics and the Communist Party, Neruda’s ideological alignment gradually shifted towards communism. Concurrently, his marital relationship underwent strain, leading to separation from his first wife in 1936. This period marked the commencement of Neruda’s association with Delia del Carril, an Argentine woman, who would later become his second wife until their divorce in the early 1950s.

The Residencia poems, initially published in 1933 and later expanded in a second edition titled “Residencia en la tierra, 1925–35” in 1935, reflected Neruda’s evolving poetic trajectory. Departing from the intensely personal and at times hermetic nature of the initial Residencia volume, this edition signaled a shift towards a more extroverted perspective and a clearer, accessible style aimed at articulating his emerging social concerns.

However, the eruption of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 abruptly interrupted this trajectory. While García Lorca met a tragic end at the hands of the Nationalists, Alberti and Hernández actively participated in the conflict. Neruda, on the other hand, engaged in efforts to raise funds and garner support for the Republicans, resulting in the publication of “España en el corazón” (1937; Spain in My Heart). This compilation of poems conveyed his profound solidarity with the Republican cause and was printed under challenging circumstances by Republican troops near the front lines.

Following his return to Chile in 1937, Neruda immersed himself in the country’s political milieu, delivering lectures, reciting poetry, and endorsing both Republican Spain and Chile’s newly formed center-left government. Appointed special consul in Paris in 1939, he facilitated the relocation of defeated Spanish Republicans who sought refuge in France. Subsequently, in 1940, Neruda assumed the role of Chile’s consul general in Mexico, concurrently embarking on the creation of his seminal work, “Canto general” (1950). This extensive poem, resonating with historical and epic dimensions, emerged as a pivotal composition within his oeuvre.

Neruda’s political trajectory within Chile took a sharp turn when, having been elected as a senator in 1945 and joining the Communist Party, he found himself at odds with the shifting political landscape. The leftist candidate he championed, Gabriel González Videla, veered towards conservatism, prompting Neruda’s disillusionment. His open criticism of President Videla resulted in expulsion from the Senate, compelling him to go into hiding in 1948. Departing Chile clandestinely, Neruda crossed the Andes Mountains with the manuscript of “Canto general” in tow.

During his exile, Neruda traversed the Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary, and Mexico. In Mexico, he reconnected with Matilde Urrutia, a Chilean woman whom he had initially encountered in 1946. Their ensuing marriage endured until Neruda’s demise and inspired some of the most fervent Spanish love poems of the 20th century. The third volume of the Residencia cycle, “Tercera residencia, 1935–45” (1947; Third Residence), marked the culmination of Neruda’s departure from egocentric existential concerns and his unreserved embrace of left-wing ideological principles. “Canto general” epitomized this ideological commitment, celebrating Latin America’s natural richness, historical struggles for liberation from Spanish colonization, and ongoing quests for freedom and social justice. Simultaneously, the epic poem lauded Joseph Stalin, the then-Soviet dictator, thereby encapsulating Neruda’s complex political stance during this period.

Later Years

In 1952, a favorable political climate in Chile enabled Pablo Neruda to return to his homeland. By this juncture, his literary contributions had gained global recognition through translations into numerous languages. Enjoying both affluence and renown, Neruda constructed a residence on Isla Negra, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, in addition to maintaining properties in Santiago and Valparaíso. His international travels, spanning Europe, Cuba, and China, marked a prolific period of ceaseless literary output and fervent creativity.

During this phase, Neruda produced one of his seminal works, “Odas elementales” (Elemental Odes), published in 1954. Distinguished by a novel poetic style characterized by simplicity, directness, precision, and humor, this collection featured odes dedicated to commonplace objects, situations, and beings, exemplified by pieces such as “Ode to the Onion” and “Ode to the Cat.” Several poems from “Odas elementales” attained widespread inclusion in anthologies. The poet’s prolificacy during these years was propelled by his international acclaim and personal contentment, resulting in the publication of 20 books between 1958 and his demise in 1973, with an additional 8 posthumously released volumes. Neruda’s reflective memoir, “Confieso que he vivido” (1974; Memoirs), provided a summative account of his life through recollections, observations, and anecdotes.

In 1969, Neruda actively supported the leftist presidential candidate Salvador Allende, who, upon election, appointed Neruda as the ambassador to France. While grappling with prostate cancer during his tenure in France, Neruda received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971. After attending the award ceremony in Stockholm, he returned to Chile in an ailing state. Tragically, Neruda outlived his close friend Allende by a brief period, with Allende succumbing to suicide on September 11 amidst a right-wing military coup.

Controversy shrouds the circumstances of Neruda’s demise, and various studies of his remains have not definitively resolved the cause of death. Despite substantial skepticism concerning the initially cited cause (cancer-related wasting), assertions persist that Neruda may have been poisoned due to his opposition to Augusto Pinochet, the military leader who wrested power from Allende’s government.

Legacy

Pablo Neruda’s literary legacy, characterized by its vast and diverse poetic corpus, resists facile classification or succinct encapsulation. Nevertheless, discernible trajectories within his oeuvre manifest along four primary thematic directions. Firstly, his love poetry, exemplified by the youthful “Twenty Love Poems” and the more mature “Los versos del Capitán” (1952; The Captain’s Verses), is imbued with tenderness, melancholy, sensuality, and ardent passion. Secondly, in what may be termed “material” poetry, as evidenced in “Residencia en la tierra,” Neruda delves into themes of loneliness and depression, immersing himself in a subterranean realm populated by dark, demonic forces. Thirdly, his epic poetry finds its apotheosis in “Canto general,” a Whitmanesque endeavor to reinterpret the historical and contemporary narrative of Latin America, particularly the struggles of its oppressed masses seeking emancipation. Lastly, Neruda’s poetic exploration of commonplace, everyday elements — objects, animals, and plants — as seen in “Odas elementales,” constitutes the fourth facet of his creative expression.

These thematic strands seamlessly align with distinct facets of Neruda’s personality: his fervent love life, the psychological turbulence experienced during his consular service in Asia, his unwavering commitment to political causes, and an enduring attentiveness to the minutiae of daily existence, manifesting as an appreciation for artifacts crafted or cultivated by human hands. Works like “Libro de las preguntas” (1974; The Book of Questions) further reveal Neruda’s contemplative engagement with philosophical and whimsical inquiries regarding humanity’s present and future.

Pablo Neruda, a profoundly original and prolific 20th-century Spanish-language poet, produced an extensive body of work, showcasing thematic diversity. Despite the eclectic nature of his output, each individual book maintains a cohesive unity in style and purpose. The comprehensive collection of Neruda’s work is compiled in “Obras completas” (1973; 4th ed., expanded, 3 vol.). Various English translations render the majority of his oeuvre accessible, with notable translations including “Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair,” translated by W.S. Merwin (1969, reissued 1993); “Residence on Earth, and Other Poems,” translated by Angel Flores (1946, reprinted 1976); “Canto general,” translated by Jack Schmitt (1991); and “Elementary Odes of Pablo Neruda,” translated by Carlos Lozano (1961). “All the Odes” (2013) presents Neruda’s odes in both the original Spanish and English translation. Additionally, “Then Come Back: The Lost Neruda” (2016) features a collection, in Spanish and English, of 21 previously unpublished poems discovered in his archives.