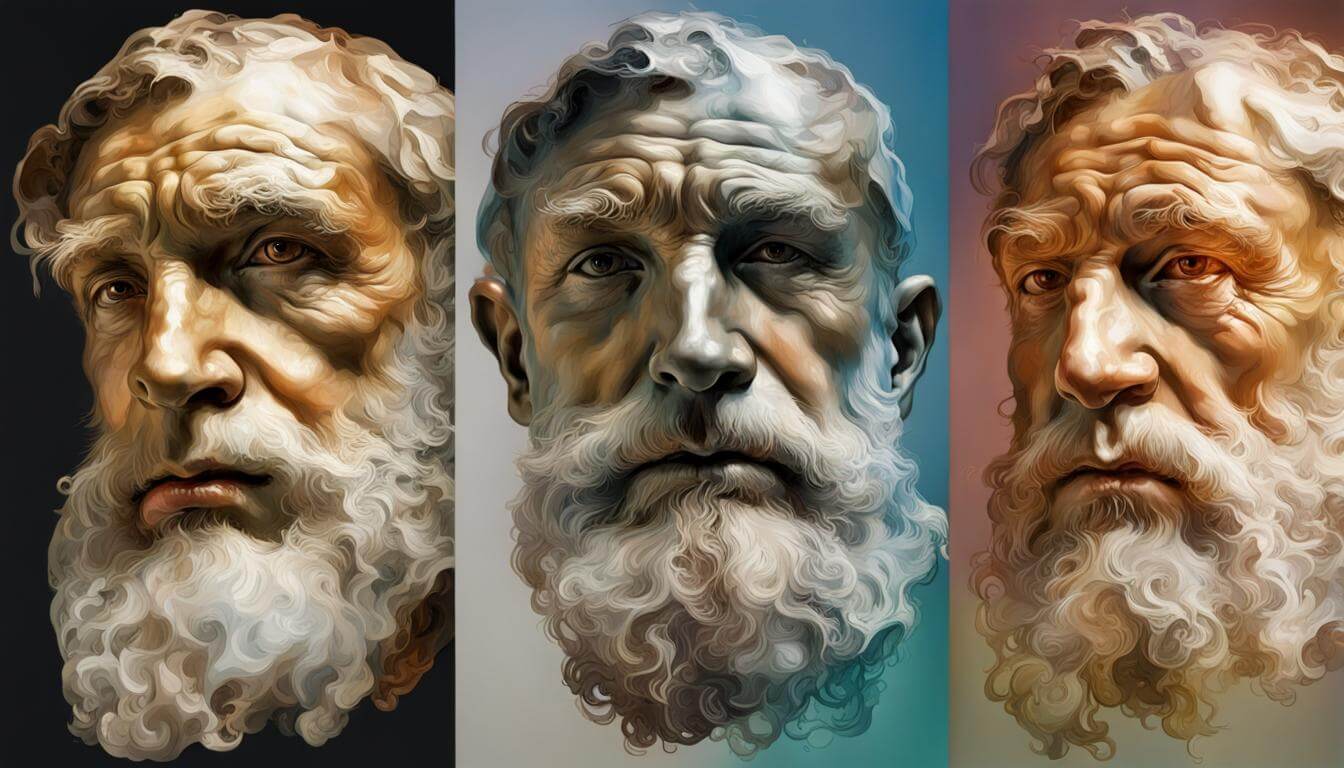

Explore the life and legacy of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), the renowned French sculptor who revolutionized art by breaking free from academic classicism. Rodin’s journey from a self-taught sculptor to a global icon was marked by his pursuit of truth and beauty, capturing the essence of human experience.

Auguste Rodin; (1840-1917), French figure and portrait sculptor, who, at his death, was perhaps the most famous contemporary artist in the world and who remains France’s most distinguished sculptor. His importance rests on the role he played in releasing artistic expression from the strictures of academic classicism, which required that sculpture provide an ideal image of man. In seeking new solutions to the problem of what constitutes truth and beauty in sculpture, he transformed the conditions of reproducing the human figure in order to realize faithfully his own experience and thereby bring art closer to life. He was criticized for showing people more than they wanted to see of suffering and sex and, in terms of his partial figures, less than they expected to see artistically.

Early Career

François Auguste René Rodin was born in Paris on Nov. 12, 1840. His father was a minor police functionary. His mother encouraged his artistic bent. From 1854 to 1857 he attended the École Nationale de Dessin to be trained in drawing and sculpture for work as an artisan. One of his teachers was Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, whose ideas of sketching from memory provided the basis for the continuous drawing method—that is, observing models in motion and drawing them without looking at the paper—that Rodin evolved in the 1890’s.

Three times, in 1857-1858, Rodin failed the sculpture entrance examination for the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts and, as a result of his lack of formal training, had to develop his own way of working as a sculptor. In 1860, from an artisan, Constant Simon, he learned to model subjects in depth by seeing them in foreshortening.

Briefly, after the death of his beloved sister Maria in 1862, Rodin studied for the priesthood, but the next year he gave up the religious life to become an artist. For more than two decades, to support himself, he worked for other artists, including Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, doing decorative pieces that were signed by his employers. In the meantime he was busy observing sculpture in the Louvre, where he came into contact with the works of Michelangelo. Michelangelo, whom he studied more extensively during a trip to Italy in 1875, taught Rodin the potential drama of the human figure and gave him a taste for heroic bodies.

What made Rodin a revolutionary in art was his confrontation with life, working directly from unprofessional models in all their profiles rather than from a few fixed views and accepted poses. His first effort in this method—and his first masterpiece—was the masklike The Man with the Broken Nose, which was rejected for exhibition by the Salon of 1864.

Middle Career

In the Salon of 1877, Rodin exhibited his first statue under his own name—a plaster cast of The Age of Bronze (originally titled The Vanquished). The work won some praise, but, because of its extreme realism, provoked charges that Rodin had cast it directly from the human figure. The Age of Bronze, intended as a patriotic image of France’s disillusioned youth after defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, was an expression of Rodin’s effort to phrase monumental subjects in a personal, humanized language. This tendency was to result in unfavorable criticism that plagued Rodin throughout his life. For example, two projected monuments, The Defense (1878) and Balzac ( 1897 ), were rejected, and The Burghers of Calais (1884-1886) aroused bitter controversy because it showed the pathos, not the stoic heroism, of a group of medieval political martyrs.

Despite severe criticism, Rodin won supporters, and in 1880 he received a commission from the French government to design a pair of doors for a projected museum of decorative arts in Paris. This enormous project, known as The Gates of Hell, was to absorb Rodin for the rest of his life and remain unfinished when he died. Begun to illustrate Dante’s Inferno, The Gates of Hell evolved into Rodin’s personal epic of man’s spiritual confrontation with modern life. This brilliant, pessimistic monument to human suffering and despair was the source of many of Rodin’s major works, including The Thinker, The Kiss, The Shades, The Prodigal Son, The Crouching Woman, The Head of Sorrow, and Meditation.

Later Career

Beginning in the mid-1880’s, Rodin achieved unqualified critical and commercial success as a portrait sculptor. In his portraits, among the most important of which are those of Victor Hugo (1883), Georges Clemenceau (1911), and Pope Benedict XV (1915) and the anonymous Head of Iris (1890-1891), he attempted to present not just a likeness of his subject but to capture, almost psychoanalytically, inner conflicts and emotions. He further believed that the entire figure could be as expressive as the mouth, and, therefore, his nudes as well as his heads show us not only what people looked like but what they felt.

By the time of his exhibition in 1889 with the painter Claude Monet at the Georges Petit Gallery in Paris, Rodin had achieved national recognition, and his financial situation improved so that in 1900 he could have an extensive one-man show in Paris, which won him worldwide commissions. As many as 40 carvers worked for him in meeting the demand for his marble sculptures. From 1890, Rodin won honors, had international exhibitions, and played an important role in helping younger artists by his influence with the National Society of Fine Arts that sponsored annual sculpture exhibitions.

By 1900, Rodin was convinced that a complete work of sculpture need not suppose the entire human figure: the part could stand for the whole. The partial figure—expressive torsos and hands that gave a new terseness and formal emphasis to art—was his most influential contribution to modern sculpture. An example is his headless, armless Walking Man (1905), enlarged from an earlier torso and legs used as a study for John the Baptist (1878). He also emphasized the self-reflexive aspects of sculpture by calling attention to the accidents and marks of its making. In effect, he proposed the alternative of “completeness”—that is, stopping work when an idea or certain effect has been realized—to the academic concept of scrupulous finish. Rodin thought of himself as a “worker” but was, in fact, an unintentional revolutionary. He bridged traditional figural art and 20th century sculpture and became a forceful presence against whom every venturesome young sculptor had to take a stand in order to find his own individuality.

Rodin died on Nov. 17, 1917, at his estate at Meudon, near Paris. The year before his death he gave his art to the French government, and in his honor the Musee Rodin was built in Paris.