What is the review, content, historical context and purpose of Book of Daniel? Information on the summary of Book of Daniel.

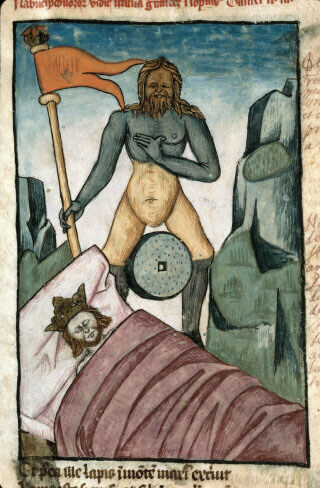

Nebuchadnezzar’s dream: the composite statue (France, 15th century) (Soyurce : wikipedia.org)

Book Of Daniel; one of the books of the Old Testament, listed among the “Writings” in the Jewish Scriptures. Christians have traditionally grouped it with the Prophets. It recounts the story of a Jew who, during the national exile in the 6th century b. c., served as a scribe in the courts of Babylon and Persia.

Dating.

Numerous features of the story indicate that it does not date back to the Babylonian or Persian periods. For one thing, the collection of Hebrew Prophets was complete about the end of the 3d century b. c., but it does not include Daniel, which is found only among the later collection, the Writings. The catalog of famous Hebrew ancients published in the Wisdom of Sirach (near the start of the 2d century b. c. ) does not mention Daniel, yet a century later I Maccabees alludes to the book. A long portion of the book is in Aramaic—not in the dialect of Mesopotamia, but in that of Palestine.

Many historical details of the earlier periods have been badly garbled, in contrast with the meticulous accuracy of Ezra. Darius the Mede is confused with Cyrus the Persian. Xerxes, Darius, and Cyrus are listed as reigning in that order, when the reverse is correct. However, the author displays considerable acquaintance with events of the Greek period. He also presents many religious concepts, such as belief in resurrection and angels, that developed in about the 2d century b. c. All this has led scholars to agree that Daniel was published in Palestine about 165 b. c., during the persecution of the Syrian king Anti-ochus IV Epiphanes.

Historical Context and Purpose.

Palestine came under Greek rule when all Persian provinces were annexed by Alexander. After his death in 323 the empire was divided among his generals, and two dynasties, the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria, contended for control of the tiny buffer state. In 167,””Antiochus, anxious to reinforce Syrian rule in Judah, decreed that all subjects must abandon the Jewish faith and conform to the Greek state religion. His harsh repression of nonconformists provoked a rebellion that combined nationalism with piety. The book of Daniel was an underground publication designed to encourage Jews within the resistance movement. Drawing on old legends about a Jewish sage named Daniel (see Ezekiel 14 and 28), who had been warmly remembered from exile days, the author tells a tale of a great Jew who had defiantly observed the law of God under harrowing persecution.

Content.

The first six chapters present six separate narratives. In die first chapter, Daniel and three other Jewish youths in the royal scribal school at Babylon excel all the sages of the country because they are secretly abiding by the kosher dietary laws of their people. Chapter 2 finds Daniel interpreting King Nebuchadnezzar’s dream. A great statue with a golden head, silver arms and chest, bronze belly and thighs, iron calves, and feet of iron and clay alloy is struck by a stone on the feet, topples over, and disintegrates. The image, Daniel explains, stands for the succession of foreign empires that would occupy and rule Judah: Babylon, Media (which is one of the book’s anachronisms), Persia, Greece, and Egypt-Syria. The Jews will vanquish this last power, and end an era of subjection. “And in the days of those kings the God of heaven will set up a kingdom which shall never be destroyed, nor shall its sovereignty be left to another people. It shall break in pieces all these kingdoms and bring them to an end, and it shall stand for ever” (2:44). The author has thrown back into the past a prediction of the Jewish revolt he senses is about to begin.

In the next story, Daniel, appointed First Scribe of the realm, joins his three Jewish colleagues in refusing to join the national worship of the King’s image. When Daniel’s friends Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego survive the fiery furnace, the King gives credit to their God’s ability to rescue his believers. The fourth episode portrays Daniel interpreting another royal dream: the King is to endure seven years of madness for his pride. After his recovery he praises the God of the Jews who can humiliate the greatest of rulers. Chapter 5 is the tale of Belshazzar’s feast, in the course of which Daniel predicts the overthrow of the empire of the Babylonians because they have profaned the temple in Jerusalem. In the last narrative, Daniel ignores the King’s injunction that for one month none but he must be worshiped. He survives the lion’s den and brings Darius to acknowledge the Lord of the Hebrews.

Thus, by his fictional narratives about a faithful Jew some 400 years in the past, the writer of Daniel is encouraging his compatriots to stand fast by their faith and its unusual practices: kings greater than Antiochus have been brought to their knees before Yahweh, God of the Hebrews.

The remaining six chapters shift into an entirely different literary style, that of apocalypse. Daniel recounts a series of four allegorical visions that contain extraordinary imagery. The point is always the same: Judah will soon be avenged by the Lord, who will found His own kingdom and bring the struggles of history to a close by ruling all men Himself. In the first vision (7:1-28), four rapacious beasts are seen (the empires), the last sprouting a particularly vicious horn (Antiochus). The Lord, pictured as an ancient king, sits in judgment and has the last beast destroyed. The saints of the Most High (faithful Jews) are given world rule: “And behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man [Judah], and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him; his dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and his kingdom one that shall not be destroyed” (7:13-14).

The second vision (8:1-27) pictorializes the clash of empires in a fight between a ram and a goat—ending in the symbolic destruction of them all. In the next dream (9:1-27) Jeremiah’s prophecy that Jerusalem’s desolation will last 70 years (he was guessing how long the Babylonian exile would endure) is extended to 70 weeks of years, the author’s rough reckoning of the total time Judah has spent deprived of independence. The time, Daniel is told, is almost up. The final vision (10 to 12) is an elaborate and symbolic history of recent political struggles, ending in the Lord’s dispatch of Michael, his captain, to eliminate Antiochus. The resurrection of the dead is first taught in Hebrew literature in this final vision: Jews who have lost their lives for their faith will rise to glory, and their persecutors to perpetual contempt.

mavi