Dive into the life, works, and novels of James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), the influential American author best known for his Leatherstocking Tales, including ‘The Last of the Mohicans.’ From his early life and frontier experiences to the creation of iconic characters like Natty Bumppo, uncover the significant literary and social contributions of this groundbreaking writer in American history.

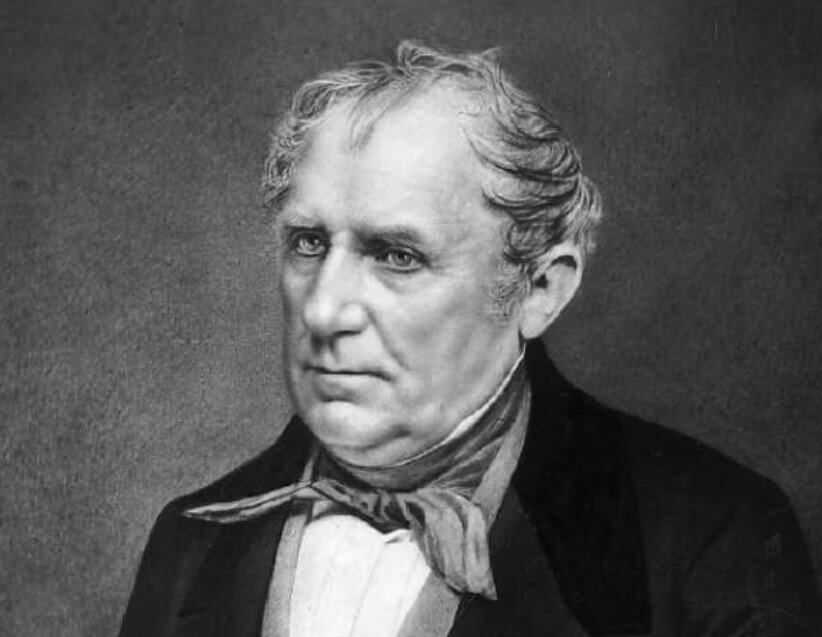

James Fenimore Cooper; (1789-1851), American novelist, historian, and social critic, who was the first great professional author in the New World. He is most famous for the Leatherstocking Tales about the American frontier, of which the best known is The Last of the Mohicans (1826). As both interpreter of and contributor to the developing national culture, Cooper occupied—as his contemporaries at home and abroad sporadically recognized—a unique and central position. He implicated himself personally, intellectually, and creatively in the American civilization he saw evolving, and committed himself fervently to a magnificent 18th century vision of its possibilities.

Early Life:

Cooper was born at Burlington, N. J., on Sept. 15, 1789, the son of Quakers, Judge William Cooper and Elizabeth Fenimore Cooper. A representative to the 4th and 6th Congresses, Judge Cooper was a prominent Federalist who attained great wealth by developing large tracts of virgin land. The Coopers moved, when James was about a year old, to the thriving frontier village of Cooperstown, N. Y., which Judge Cooper had founded a few years before. James (“Fenimore” was added later, in deference to his mother) indulged himself—almost too deeply —in the freedom conferred by both wealth and wilderness. He was an undisciplined student and was expelled from Yale in his junior year for frivolity. He was then sent to Europe as a common seaman to prepare for a naval career.

In 1808, on his return to the United States, Cooper received a warrant as a midshipman in the Navy. Three years later he married Susan Augusta De Lancey, who came from a powerful New York Tory family, and shortly thereafter, with his wife’s urging, and on the strength of a large inheritance from his father, who had died in 1809, he left the Navy. Cooper took up the comfortable life of a gentleman farmer, first in Westchester county, New York, and then on a fine farm in Cooperstown, overlooking Lake Otsego. However, serious reverses connected with his father’s estate destroyed this idyll, and Cooper returned to Westchester in 1817, living modestly on his wife’s land.

At the age of 30, inspired by a school of best-selling novels and a need for cash, he wrote his first novel, Precaution (1820). Though the work was a failure, Cooper had found his métier, and his next novel, The Spy (1821), in which he created Harvey Birch, a humble spy for the American revolutionaries, was widely acclaimed.

Leatherstocking Novels:

Cooper’s next work, The Pioneers (1823), extended his reputation, both at home and abroad, and marked the start of his Leatherstocking series. These novels, which have become classics of American literature, tell the adventures of the American forester-frontiersman Natty Bumppo (also called Leatherstocking, Hawkeye, and other names) and his Indian companion Chingachgook. The novels were not written in the chronological order of their narrative; their story starts with what was actually the last-published work in the series—The Deerslayer (1841), which depicts Bumppo in his youth in the Lake Otsego region. The Last of the Mohicans follows Natty s exploits against the Huron Indians in the Lake Champlain region; The Pathfinder (1840) tells of Bumppo’s adventures in the French and Indian War, and portrays him in love; The Pioneers shows Natty and Chingachgook as old men in the Lake Otsego region; and The Prairie (1827) depicts Bumppo’s last days, as a trapper on the Great Plains, where he was driven by the destruction of the forests in the East.

Sea Novels:

Having created the genre of the frontier tale, Cooper invented, with The Pilot (1824), the genre of the sea romance, filled, like the forest tales, with rapid action and strongly contrasted characters. His other novels with sea settings include The Red Rover (1827), The Wing-and-Wing (1842), The Two Admirals (1842), Afloat and Ashore (1844), and its sequel Miles Wallingford (1844), and The Sea Lions (1849).

Social Criticism:

Cooper’s long conflict with his critics began to erode his popularity in the early 1830’s, during the latter part of his residence in Europe (1826-1833). There he continued to write romances but turned increasingly to types of writing in which he could embody his maturing philosophy of political, economic, and social behavior. Cooper’s readers had been satisfied with his earlier work, historical romances with recognizable American scenes, characters, and manners. But when he turned his energies to educating his countrymen on their cultural deficiencies, he met with scorn and severe opposition. Deeply persuaded of the necessary coexistence of order and individuality in human affairs, he sought to redress the balance, to suggest the advantages of order to a society impatient of restraints. He was, that is, a constitutionalist in the broad as well as in the narrow sense, an individualist who understood the need for setting bounds to individualism.

Acute though his observations were and faithful though he sought to be to the Founding Fathers’ notion of American democracy, Cooper’s program proved to be too strenuous, too much at odds with the moving forces of his time. The first of these critical works, Notions of the Americans (1828), which was intended to refute what Cooper considered to be false accounts of America by European travelers, was reviewed with hostility in Europe and ridiculed by American journalists. Three new romances with European settings, The Bravo (1831), The Heidenmauer (1832), and The Headsman (1833), also containing social commentary, received harsh treatment in the American press.

Returning to the United States in 1833, first to New York City and later to Cooperstown, Cooper chronicled his ill-treatment by American journalists in A Letter to His Countrymen (1834). This was followed by The Monikins (1835), a political allegory; five European travel books; The American Democrat (1838), which set forth more systematically his views of government and society; and two novels reflecting his bitter disappointment with America, Homeward Bound (1838) and Home As Found (1838)—all of which were badly received, as was his monumental History of the Navy of the United States of America (1839). Cooper challenged his critics, mostly prominent Whig editors, in numerous libel suits designed to expose the tyranny of the press, and won most of his cases.

Later Years:

Remaining the disappointed, uneasy American, Cooper nevertheless regained some popularity with later publications, among them the final Leatherstocking novels, The Pathfinder and The Deerslayer. Other late works were Satanstoe (1845), The Chainbearer (1845), and The Red-skins (1846), a trilogy that chronicled the history of the Antirent troubles in New York state; Ways of the Hour (1850), a murder mystery with much social commentary; and Upside Down (1850), a play ridiculing socialist ideas. Cooper died at Otsego Hall, his home in Coopers-town, on Sept. 14, 1851.

Significance:

Cooper’s permanent value to social and intellectual historians as a sensitive, encyclopedic barometer of his time seems assured. Though his commentary is widely scattered throughout his writings, and some of it is cranky, precipitate, and biased by class associations, his powers of observation were as comprehensive as Tocqueville’s, and quite as suggestive.

Literary criticism has yet to give full credit to the richness and complexity of Cooper’s art. Critical judgment has too often ended with Cooper’s literary faults, especially his carelessness and turgidity, qualities ridiculed in Mark Twain’s famous essay, Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses (1895). Modern critics are beginning to discover the complex internal designs that made Cooper’s work admired by such writers as Goethe, Balzac, and Conrad. The full recognition that Cooper was a serious artist will come with the further recognition that, beyond his inventiveness and his pioneering use of American materials, his fiction, at its best, conveys a profound understanding of the human condition.