What does theology study? Information about the sources, formative factors, history and development of theology.

THEOLOGY is an intellectual discipline that aims at setting forth in an orderly manner the content of a religious faith. This definition already indicates some of the peculiarities of the subject. Calling theology an intellectual discipline involves the claim that theology has its legitimate place in the spectrum of human knowledge and the claim that it can make true statements. Therefore it can also point to defensible intellectual procedures in support of these claims. Theology has in fact often been called a science. The very formation of the word “theology” suggests a kinship with a whole range of varied scientific enterprises designated by similarly formed words —geology, psychology, topology, and the like. However, the fact that there are also pseudo sciences like astrology with similarly formed names may give us pause. Indeed, when the definition of theology goes on to say that the subject deals with the content of a religious faith, a sharp distinction seems to be made between theology and the recognized secular sciences.

It has rarely been claimed that a religious faith is itself rationally demonstrable. Religious faith is a total human attitude, including such elements of feeling and emotion as trust and awe, and of willing, such as striving and obedience, as well as of belief. Can even a reflective attempt to give expression to the content of such a faith claim to be a science, or a genuine intellectual discipline at all? Does not the acceptance of such a faith as its starting point rule out the openness and integrity that are essential to all intellectual disciplines worthy to be counted among the branches of human knowledge? Certainly, it must at once be acknowledged that in spite of the similarity of names, theology is quite a different kind of enterprise from geology. If we substitute English roots for Greek ones, geology becomes “earth-science” and theology “God-science.” This draws attention to one fundamental difference between them. Whereas the earth’s crust is something visible, tangible, and accessible to the senses in general, God, however we may think of him, has none of these characteristics.

From this difference in subject matter, there immediately follows another in method. Geology can and does apply such well-tried scientific methods as measurement, chemical analysis, observation, experiment, and so on. None of these methods is open to the theologian. It would seem that he must fall back on investigating the experiences that people describe with the aid of language about God. However, we must notice that the theologian does not simply describe and analyze such experiences as an outside observer, in the way that a psychologist or even a philosopher of religion might do. Because he is interested in the claims of faith to truth, the theologian cannot rest with an empirical description of the phenomenon of faith. He must raise the question of the validity of the experience and offer an interpretation of its inner springs. This he can scarcely do without himself being a participant in the experience. Thus theology differs from the natural sciences in being a form of knowledge by participation rather than knowledge by observation.

Source : pixabay.com

At least since the time of the German philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911), it has been recognized that there are some intellectual disciplines—the so-called “human sciences,” for example, history—whose subject matter can be known only from the inside, by participation. Clearly, theology has more affinity to these human sciences than it has to the natural sciences. Yet even in relation to these disciplines there is difference as well as similarity, for theology claims, finally, to be in some sense not just a human science; it also purports to be a divine science.

As St. Thomas Aquinas recognized when he discussed whether theology is a science, there are many kinds of sciences and intellectual disciplines —a fact that has also been increasingly recognized as a result of modern logical analysis. There are also many kinds of investigative procedures adapted to different kinds of subject matter. There is no single model to be laid down in advance and to which every discipline must conform. Rather, each discipline must be questioned about the sources and credibility of its data, the methods that it employs in investigating and interpreting these data, and the claims to truth that it makes for its conclusions. The definition of theology given above and the claims implicit in it cannot be judged by the fact that this discipline has peculiarities differentiating it from other disciplines. They can be judged only by a fuller discussion of the sources and procedures of theology.

SOURCES AND FORMATIVE FACTORS

Prior to theology is faith, an orientation of the whole person, or even of the whole community that shares a particular faith. Theology is fides quaerens intellectum—iaith seeking an understanding of itself, both its content and its ground. But what creates a faith? In traditional language, faith is itself the response to revelation.

Revelation.

The word “revelation” is, unfortunately, often misunderstood. A revelation is not a body of ready-made truths that are somehow made known to the recipient and placed at his disposal, as if this were some easy way to truth, in contrast with the hard-won discoveries of natural science. A revelation is rather a profound experience in which there comes about a whole new way of perceiving the world and understanding the place of human life in it. Things are perceived in new relationships and new depth, and the horizons of self-understanding are expanded. New values take the place of old ones and there is a new orientation of the self in the world. Furthermore, this new perception has a giftlike character. It is called “revelation” because it seems to come about not as a result primarily of human search but as the self-revealing of a reality to man. It must be repeated, however, that this is not to be understood as the making known of complete, ready-made propositional truths. On the contrary, any revelation places on its recipients the task of exploring, interpreting, appropriating, and applying the new perceptions that have been attained.

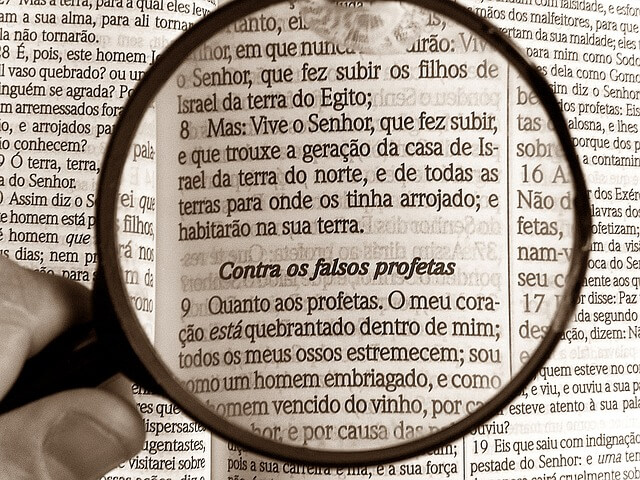

Revelations have been received in many forms. Mystical experiences are one such form. Although the term “revelation” belongs to Western rather than to Eastern categories of religious thought, it would be applicable to such Eastern experiences as the enlightenment of the Buddha— an experience of perceiving the world and human life in a profoundly new way. However, in this case there was lacking any sense of personal encounter such as has been characteristic of Judeo-Christian concepts of revelation. A theophany, or vision of a divine Being, either directly or under some visible symbolic form, has been another type of revelatory experience. Examples of theophanies are Moses’ encounter with God in the burning bush or Arjuna’s vision of the divine Krishna, as related in the Bhagavad Gïtà. In the Jewish and Christian traditions, however, historical events or clusters of events have been taken as revelations, and this is perhaps what is most characteristic of these faiths and has earned for them the description “historical religions.”

In the Jewish tradition, the Exodus of the Hebrew people from Egypt, their deliverance from slavery, and their call to be a free nation is the heart of the historical revelation. It reveals a liberating power at work in history, and this is taken to be the power of God. The historical experience of the Exodus is made interpretative for other historical situations, and it gives an identity and orientation to the community of faith that founds itself on this revelation. In the Christian tradition, the history of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, interpreted as the coming of God among men in order to bring atonement and new life, is the heart of revelation. It becomes the foundation for an entire attitude to life among those who put their faith in the revelation.

Each of the revelations mentioned has given birth to a community of faith, and so have many other revelations that have not been mentioned. In each community there has arisen a theology-Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, Islamic, Christian—that has taken that revelation as its primary datum, has reflected upon its meaning, and has sought to discover its implications for the life of the community. Does the fact that the theologian accepts the revelation accorded to a particular community as his primary datum imply that he begins with an assumption that is incompatible with a truly scientific or intellectually sound inquiry? That does not follow. Every investigation has its presuppositions. They cannot be avoided if the investigation is to get off the ground. What is important is that they should be recognized as presuppositions so that their plausibility or implausibility may be examined.

The theologian acknowledges revelation as his presupposition. Some theologians are prepared to leave the matter there, but others seek to develop a theory of revelation that may make the occurrence of revelatory experiences more readily credible. Some Jewish and Christian theologians and philosophers of religion have used the model of an encounter between persons to illuminate the nature of a revelatory experience. Again, the model of aesthetic experience—that is, of being grasped by a work of art as a whole—offers a parallel that helps to elucidate some forms of revelation. This is especially the case with those reported in mystical and Eastern religions.

The very use of the word “faith” indicates that accepting any revelation involves a risk, but the risk need not be taken uncritically. The fact that revelatory experiences with a broadly similar structure have been reported from so many human communities over such a long period of time is a presumption in favor of the prima facie validity of such experiences. To be sure, the diversity of revelations is great, and so the question of their compatibility also arises. Some theologians acknowledge only the revelations accepted in their own communities. Others, while not embracing any facile syncretism, stress what is common to the religions and believe that there are deep affinities among the many revelations.

Source : pixabay.com

Scripture and Tradition.

The great classic revelations on which the major faiths of mankind have been founded now lie in the past and are not directly accessible. Thus, although revelation is the primary datum for theology, revelation has to be mediated in various ways. It is through these mediated forms that it enters into theology. In most communities of faith, revelation is mediated by scriptures and by tradition. Scripture itself begins as oral tradition. Even at that stage the form may be rigidly fixed, and once the words have been committed to writing the verbal form tends to remain unchanged over long periods. Scripture is not itself revelation, but it is a witness to the revelatory experience. Scripture serves as the memory of the community. Through the scriptural witness, the original classic revelation continues to come alive and to shape the life of the community.

Almost all communities of faith beyond the primitive level have developed their bodies of scripture, but different communities value them in different ways. In Eastern religions there is not the same regard for the precise literal words of scripture as there is in the Middle Eastern and Western religions of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. It is true that several centuries of Biblical criticism have eroded the authority of the Bible in the West. Few contemporary theologians would adopt the style of theology common in the Protestant churches in the years after the Reformation, when theology was little more than a commentary on the Bible and when every doctrine had to be supported by the quotation of “proof” texts.

Yet even the more liberal attitude to the Bible prevailing in the late 20th century does not take away its normative significance for Jewish and Christian theology. It remains the authentic witness to the revelatory history on which these communities of faith have been founded. Modern theologians in the Judeo-Christian tradition handle the Bible with much more freedom than did their predecessors, but Biblical teaching still remains a foundation of their thinking. They could not relinquish it and still validly claim to represent theology within their particular communities of faith.

Alongside scripture there is tradition. As well as the written record, there is the continuing life of the community. This, too, has its origin in the classic revelation and helps to mediate it. Scripture and tradition are not to be considered rivals, though they have sometimes been so considered in disputes between the Catholic and Protestant forms of Christianity. The latter stress the exclusive authority of scripture, and the former admit tradition alongside scripture. But even the most extreme Protestant groups have not been able to exclude the influence of tradition. In Christianity some traditional interpretations of the revelation, such as the trinitarian doctrine of God and the doctrine of the two natures of Christ, have come to be accepted as having a high degree of authority. They are, of course, compatible with scripture, but they go beyond the explicit formulations of scripture and rule out some other possible interpretations.

Just as contemporary theologians may not feel themselves so closely bound by scripture as did the theologians of an earlier time, so they may also feel themselves less tied by traditional interpretations. Nevertheless, since it is the faith of a community to which the theologian tries to give expression, he will not recklessly set up his individual judgment against the collective wisdom of his coreligionists. To that extent his theology continues to be guided by tradition. Yet he will always be seeking new interpretations of the traditions and striving to let his theology express the tension between the continuity of the past and the novelty of the future.

Experience.

In addition to revelation, as mediated through scripture and tradition, a second main source for theology is experience. It would be hard to believe in the revelations made long ago unless there were some present experiences of the divine analogous to them. Thus the theologian’s own experience of participation in the life and worship of a community of faith become data for his theology. William James has given a classic description of the almost endless varieties of religious experience. This variety of individual experience contributes in turn to the variety of theology.

Not only so-called “religious” but secular experiences as well are sources of relevant data for theology. Present experience, secular and religious alike, is brought into confrontation with the revelation and interpreted in the light of it. In this process, the understanding of the revelation is enlarged and deepened or, in some instances, put in question. Conversely, the understanding of present experience is likewise deepened. No theology could be persuasive that had not been exposed to the test of experience, received some confirmation in experience, and incorporated something of the wisdom and actuality of experience.

Culture.

To speak of present experience is to acknowledge still another factor that enters into the construction of a theology, namely the cultural environment in which the theologian works. Some theologians have tried hard to present a theology of revelation alone, and to exclude all cultural influences. They have represented a vain hope. All human statements, including theological statements, are to some extent historically conditioned. They employ the language and thought-categories of a given period and belong to a particular moment in time.

Because of the importance of tradition in religious faith, theological formulations tend to become absolutized. They are taken to be timeless truths and persist long after the thought-categories in which they were expressed have become obsolete. This has been a major source of trouble in the history of theology. It has not been understood that theology, as much as any other science or intellectual discipline, is a dynamic study. It must continually seek new formulations and address itself to new cultural situations. This is not simply a question of translating its dogmas from one cultural idiom to another. It implies a development and deepening of the dogmas themselves as they come to be seen within new and broader cultural horizons. The progress of theology takes place as its traditional wisdom seeks to find expression in new experiential and cultural situations.

Reason and Conscience.

Related to the factors just discussed are the contributions made to theology by the reason and conscience of the theologian himself. That reason has a place in theology follows from its very definition as an intellectual discipline aiming at an ordered

body of knowledge. However, the function of theology is not merely to elucidate the content of faith but to criticize it. Likewise the theologian, though spokesman for a community of faith, has a critical function in the community.

In giving the content of faith a coherent expression, theology seeks to remove inconsistencies and obscurities within the affirmations of faith itself. It also seeks to reconcile the affirmations of faith with the other beliefs—scientific, historical, philosophical, and the like—that people hold. The strict exercise of this critical function by theology, even if it sometimes leads to clashes with ecclesiastical authority, is of the highest importance if the intellectual integrity of religious faith is to be maintained.

The point about conscience is similar. Beliefs once widely held may have to be criticized by theology as ethically objectionable, sometimes in the light of cultural developments, and sometimes in the light of a better understanding of the original revelation itself.

mavi