What is the detailed life story, biography of Dwight David Eisenhower? Information on Dwight David Eisenhower youth, career, presidency and death.

Dwight David Eisenhower; (1890-1969), American general and 34th president of the United States. He was the principal architect of the successful Allied invasion of Europe during World War II and of the subsequent defeat of Nazi Germany. As president, Eisenhower ended the Korean War, but his two terms (1953-1961) produced few legislative landmarks or dramatic initiatives in foreign policy. His presidency is remembered as a period of relative calm in the United States.

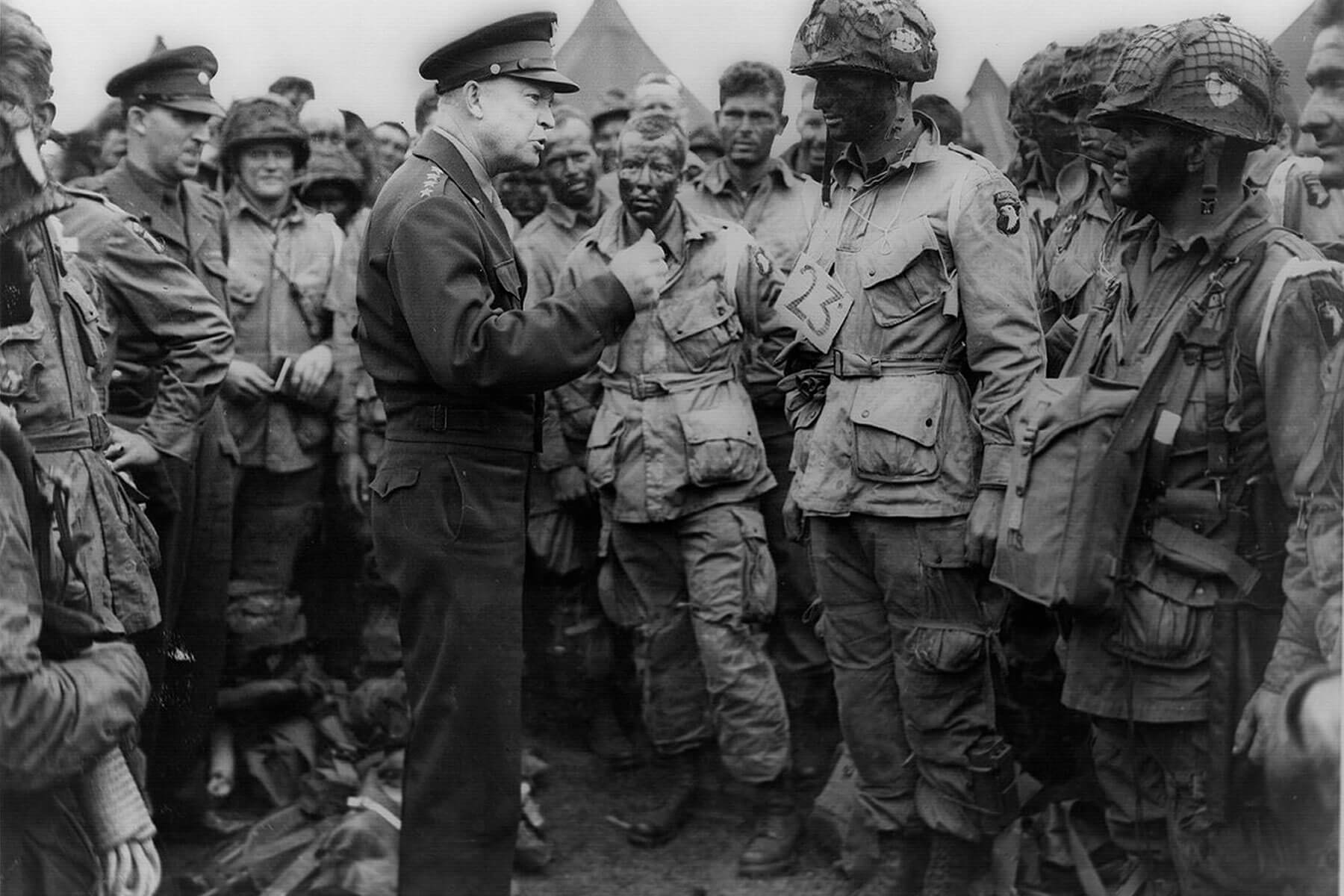

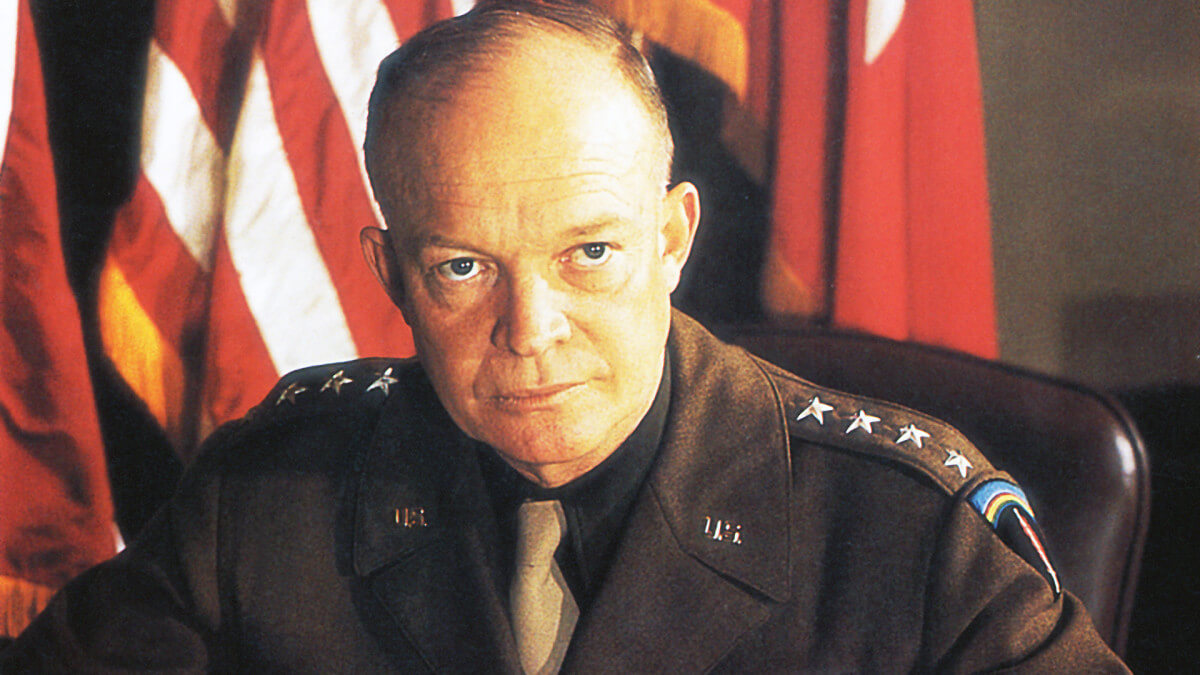

Eisenhower spent his first 50 years in almost total obscurity. A professional soldier, he was not even particularly well known within the U. S. Army. His rise to fame during World War II was meteoric: a lieutenant colonel in 1941, he was a five-star general in 1945. As supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, he commanded the most powerful force ever assembled under one man. He is one of the few generals ever to command major naval forces; he directed the world’s greatest air force; he is the only man ever to command successfully an integrated, multinational alliance of ground, sea, and air forces. He led the assault on the French coast at Normandy, on June 6, 1944, and held together the Allied units through the European campaign that followed, concentrating everyone’s attention on a single objective: the defeat of Nazi Germany, completed on May 8, 1945.

In 1950, President Harry Truman appointed Eisenhower the supreme commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization forces, thus making Eisenhower the first man to command a large, peacetime multinational force. His genips lay in getting people of diverse background to work together toward a common objective, but he was equally skillful as a strategist and administrator.

He displayed the same talents as president, but they did not produce the same spectacular results. The discipline characteristic of military organizations was unknown to American politics, and rebellion against his leadership occurred frequently—the more so because his Republican party controlled Congress during only two of Eisenhower’s eight years in office. His dislike of politics was also a handicap. He calmed fears about Communist infiltration of the national government. He provided partial relief from the divisiveness engendered by his predecessor’s approach to issues, yet Eisenhower’s achievements seem less impressive in retrospect because he minimized the importance of racial tensions and of socioeconomic antagonisms that erupted so explosively in the 1960’s.

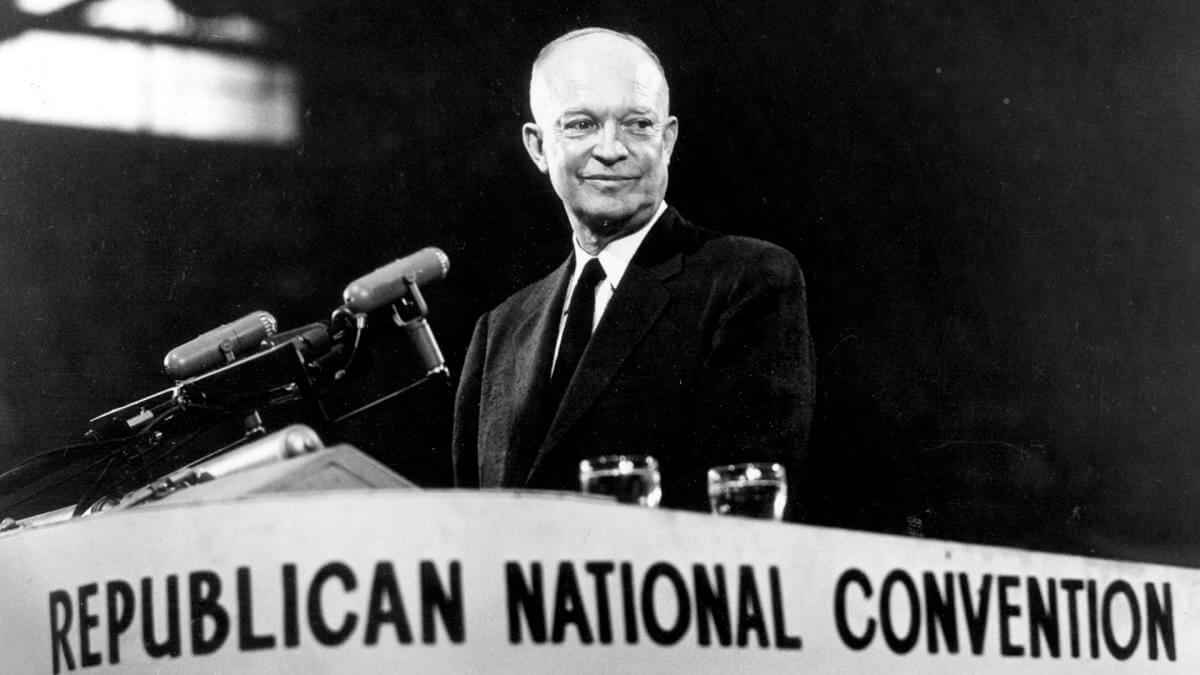

Although only a little above average in height and weight, Eisenhower dominated any gathering of which he was a member. His bald pate, prominent forehead, and broad mouth made his head seem larger than it was. He had a wonderfully expressive face, and it was impossible for him to conceal his feelings.

He had a sharp, orderly mind. No one thought of him as an intellectual giant, and outside his professional field he was not well read. He was not likely to come up with brilliant insights. But he could look at a problem, analyze it, see what alternatives were available, and choose from among them. His beliefs were those of Main Street; his personality that of the outgoing, aifable American writ large.

Almost everyone liked him. His easy manners, his obvious concern with the welfare of others, his ability to listen patiently—all contributed to his popularity. Most important was his trustworthy nature. His grin, his mannerisms, and his generosity and kindness all exuded sincerity.

Childhood.

Eisenhower’s parents, David and Ida Stover Eisenhower, both belonged to the River Brethren, a fundamentalist Christian sect. David and Ida met as students at Lane University, operated by the United Brethren Church in Lecompton, Kans. They married in 1885. David’s father, a prosperous farmer, gave him $2,000 and a 160-acre farm as wedding gifts. However, David hated the drudgery of farming and sold out, investing in a general store in Hope, Kans. Within three years the business failed, and David was broke. He fled to Denison, Texas, leaving behind a son and a pregnant wife. He worked as a laborer on a railroad for $40 a month and in 1889 sent for his family to join him in Texas. There Dwight was born on Oct. 14, 1890. When Dwight was less than a year old, David took a job at the Belle Springs Creamery in Abilene, Kans., and the family moved into a small house in Abilene. There David and Ida raised six healthy boys—a seventh son died in infancy—on a salary that never exceeded $100 a month. Each of the six surviving sons achieved success.

Ida ran a tightly organized household. The Eisenhowers raised almost all their own food, selling the surplus for cash. The boys worked to earn their spending money. David led weekly Bible reading sessions. He and Ida moved steadily toward a more primitive Christianity, eventually joining the Jehovah’s Witnesses. None of their sons became notably devout—Dwight never joined a church and rarely attended a church service in his adult life—but none staged a dramatic rebellion against religion either. At the core of his parent’s religion was an ingrained respect for the individual as a creature of God who had free will. They insisted that their boys be fully exposed to Christianity, but beyond that they did not impose their beliefs. The Eisenhowers also encouraged their children to be independent and self-reliant.

Although Dwight attracted little attention in the classroom, he stood out in athletic competition through grade school and high school. After graduating from Abilene High School in 1909, Dwight went to work in the creamery, partly to support an older brother in college. He took a competitive examination for an appointment to the U. S. Naval Academy, both because a free education was too good to pass up and because of the opportunity to play football. He passed the examination, then found that he was too old to go to Annapolis and instead in 1911 went to the Military Academy at West Point.

MILITARY CAREER

Sports were his all-consuming interest. At the academy he was average in everything else. During his second year Eisenhower played halfback on the Army team, and sportswriters began to predict All-American honors for him, but a twisted knee during the season ruined his football career. The blow to his emotions was worse. His roommate described Eisenhower as a man who had lost interest in life. Eisenhower graduated in 1915, 61st in a class of 164.

Marriage.

Two weeks after reporting for duty as a 2d lieutenant of Infantry at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, he met Mamie Geneva Doud. He immediately embarked on a courtship. Miss Doud came from a wealthy Denver family and was accustomed to a life of ease and luxury, which a young Army officer could hardly offer. She tried to discourage her suitor, but he persisted, and on July 1, 1916, they were married in Denver. The union was an eminently happy one. They had two sons. One died as a child. The other, John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower, graduated from the Military Academy on the day Dwight Eisenhower launched the invasion of Europe. John Eisenhower eventually became U. S. ambassador to Belgium.

Early Promotions.

In 1917, shortly after the U. S. entered World War I, Eisenhower was promoted to captain. He wanted desperately to go to France to lead men in battle, but he was such an outstanding instructor and trainer of men that the Army kept him in the United States. In March 1918 he took command of Camp Colt, a tank training center at Gettysburg, Pa. There he spent the rest of the war, learning a great deal about armored warfare and about turning civilians into soldiers, earning a Distinguished Service Medal for his services, but getting no promotions or combat experience. He was promoted to major in 1920 and in the next year graduated from the Tank School at Camp Meade, Md. But outward signs of progress hid inner drift. He had little interest in his profession, spent most of his time coaching football teams on Army posts, and could not see much of a future for himself.

Then, in 1922, he was transferred to the Panama Canal Zone as executive officer for the 20th Infantry Brigade. There he met Gen. Fox Conner, who stimulated Eisenhower’s interest in the profession of arms. Conner gave Eisenhower what amounted to a graduate course in military history. They spent hours talking about military and international problems. Conner told Eisenhower that a certain Col. George C. Marshall would lead the American forces in the next war—which he was certain would come—and urged Eisenhower to try for an assignment under Marshall. Conner also impressed on Eisenhower the idea that the next war would be worldwide and those who directed it would have to think in terms of world rather than single-front strategy. Even after he was a retired president, Eisenhower would say, “Fox Conner was the ablest man I ever knew.”

Staff Assignments.

In 1925, thanks to Conner’s help, Eisenhower went to the Command and General Staff School in Leavenworth, Kans. He worked hard, graduating first in a class of 275. In 1927 he prepared a guidebook on European battlefields of World War I. In 1928 he graduated from the Army War College in Washington, D. C. By this time his reputation in the Army was that of an outstanding staff officer, uncommonly good at preparing reports.

From 1929 to 1933, Eisenhower served in the office of the assistant secretary of war. He produced a long report on industrial mobilization in the event of war. In 1933 he became assistant to the chief of staff, Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Although MacArthur was too flamboyant for Eisenhower’s taste, MacArthur appreciated and depended on Eisenhower’s administrative and writing abilities. When MacArthur went to the Philippines in 1935 as military adviser to the Commonwealth, he asked the War Department to detail Major Eisenhower to him as senior assistant. Eisenhower spent the next four years in the Philippines helping MacArthur build up the defenses of the islands. He made no secret of the fact that he disliked the duty and wanted command of troops.

In early 1940, Eisenhower, now a lieutenant colonel, became executive officer of the 15th Infantry Begiment at Fort Ord, Calif., but the Army quickly sent him back to staff work. In March 1940 he became chief of staff of the 3d Division at Fort Lewis, Wash., and in 1941 rose to colonel and chief of staff for Gen. Walter Krueger, commander of the 3d Army at Fort Sam Houston. In the summer of 1941 he made the plans for Krueger’s 3d Army in the Louisiana maneuvers, the largest ever held in peacetime in the United States. Eisenhower did so well that for the first time he attracted some notice outside the Army. He was also promoted to brigadier general.

On Dec. 14, 1941, George Marshall, now Army chief of staff, called Eisenhower to Washington and put him in the War Plans Division with special responsibility for the Far East. Eisenhower was stuck behind a desk again, working 14 hours a day, 7 days a week. Marshall, who was trying to cut the deadwood out of the Army’s general officer ranks and was looking for vigorous younger men to lead the war effort, was impressed. In March 1942, he made Eisenhower a major general and head of the Operations Division. In June he added another star and sent Eisenhower to London to take command of the U. S. forces in the European Theater of Operations.

African and Italian Campaigns.

Eisenhower spent his first weeks in London participating in one of the war’s great strategic debates. Following Marshall’s lead, he urged the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS, composed of the heads of services of Britain and the United States) to plan for an invasion of France in 1943, with a possible suicide invasion in 1942 if it appeared that the Soviet Union was about to leave the war. The British insisted on an invasion of North Africa, an easier task though less likely to produce significant results. It was one of many disagreements between the British and American commands on war strategy. President Franklin D. Roosevelt sided with the British. The CCS selected Eisenhower to command Operation Torch, giving him control of all British and U. S. ground, sea, and air forces involved. It was a unique command. Eisenhower’s directive gave him far more power than Marshal Foch had exercised in 1918 in the only previous attempt to create a large allied command.

On Nov. 8, 1942, the African invasion began. Eisenhower’s forces landed near Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers. The Vichy French forces resisted. Eisenhower made a deal with their commander, Adm. Jean Darlan, giving Darlan civil control of North Africa in return for French cooperation in the war against Germany. Because Darlan was anti-Semitic and a collaborator with the Nazis and because Eisenhower was giving him vast powers, the arrangement brought a stonn of protest on Eisenhower’s head. By emphasizing the temporary, military nature of the deal, Eisenhower survived the storm.

On the ground, meanwhile, Eisenhower tried to rush his troops eastward into Tunisia before the Germans could establish themselves there. He failed. A long, dreary campaign followed, punctuated by the Battle of Kasserine Pass, in February 1943, in which the U. S. troops were caught by surprise but recovered and held their ground. In May the Germans surrendered. Eisenhower, now a full four-star general, added the British Eighth Army, under Montgomery, to his command and in July launched the invasion of Sicily. The island fell at the end of August, though most of the German defenders escaped. Eisenhower, meanwhile, had also been directing the secret negotiations for the Italian surrender.

On Sept. 8, 1943, Eisenhower’s forces invaded Italy at Salerno. The Germans, who had occupied the country and were well prepared, fought a tough defensive campaign in the mountains, and progress was slow. Eisenhower was delighted when in December the CCS ordered him to leave Italy and go to London to take command of the forces gathering in England for the invasion of France.

Invasion of France.

When Eisenhower took over Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), he found himself in command of the largest single undertaking ever attempted by man. The entire course of the war would likely turn on the success or failure of Operation Overlord. More than 156,000 men would hit the Normandy beaches on the first day, with 6,000 ships behind them and thousands of airplanes of every type overhead. To organize and direct this vast force, Eisenhower had a staff of 16,312 officers and enlisted men. He counted most of all, however, on two men. Marshall had backed him throughout the Mediterranean campaign and was giving him unlimited support in Washington. His own chief of staff, Walter Bedell Smith, was another source of strength. In the field his chief U. S. commanders were Gen. Omar Bradley, a West Point classmate and close friend, and Gen. George Patton. Eisenhower did not get along well with Montgomery, the British commander, but respected his ability.

The invasion was scheduled for June 4, 1944, but a great storm over the English Channel forced postponement. That evening the weatherman predicted that the storm would abate by the morning of June 6, providing satisfactory landing conditions. Eisenhower had total confidence in his meteorologist, based on a month of checking on his predictions every day. After consulting with his field commanders and staff, Eisenhower tentatively decided to launch the attack. On June 5 he held a predawn conference. He could still order the ships to turn back. Outside, the wind howled and the rain seemed to come down in horizontal streaks. The weatherman stuck by his prediction. Most of Eisenhower’s advisers wanted to go ahead. If he called off the invasion, it could not be launched for at least two weeks. Also, the secret of the landing site would almost certainly become known to the Germans because 160,000 men had been briefed. If the storm did not subside, however, the invasion landing craft would be tossed on the beaches and Overlord would fail. Only Eisenhower could decide. He thought for a moment, then said quietly but clearly, “O.K., let’s go.”

The weather cleared and the troops got ashore. For the next month and a half Eisenhower built up his forces in Normandy, meanwhile urging Montgomery to take more aggressive action in the vicinity of Caen so that the SHAEF forces could move on to Paris by the most direct route. Montgomery, however, insisted that his chief task was to tie down heavy German forces so that the Americans on his right could break out of the beachhead.

In late July the Americans did force a breakthrough, and the drive through France began. Almost immediately Eisenhower was locked in another controversy with Montgomery. The British general urged the supreme commander to give the British troops on the left all available supplies so that he could lead a drive into northern Germany. Eisenhower insisted on advancing along a broad front, with Bradley’s American troops on the right staying about even with Montgomery’s troops. Montgomery charged that Eisenhower’s caution prolonged the war. Eisenhower believed that if he gave all the drastically limited supplies—SHAEF’s major problem was the absence of deepwater ports—to Montgomery and allowed him to drive into Germany, the troops involved in the single thrust would be isolated and destroyed by the enemy. In addition, Eisenhower thought it politically impossible to halt the Americans—especially Patton—in the Paris region while Montgomery drove for Berlin and glory. He insisted on the broad front in the face of the strongest protests from Montgomery, the British chiefs of staff, and Prime Minister Churchill. He had his way, partly because of Marshall’s support, mainly because of his own growing self-confidence.

By late autumn the SHAEF forces had outrun their supplies. Although they had driven the enemy from France, they had been unable to penetrate Germany. In December 1944 the Germans began a massive counterattack in the Ardennes region. In the resulting Battle of the Bulge, Eisenhower, his staff, and most of all the troops recovered quickly and soon plugged the breach in the Allied lines. Eisenhower, now wearing five stars, approached the Rhine along a broad front, destroying the bulk of the German forces in a brilliant campaign.

Berlin Controversy.

The question now concerned the direction the advancing forces should take. Churchill wanted Eisenhower to capture Berlin and hold it until the Russians made concessions on Poland and other political questions relating to the fate of postwar eastern Europe. Eisenhower insisted that prior agreements between the Allied governments—agreements that had divided Germany into occupation zones and Berlin into sectors within the Russian zone—made the nationality of the troops who took Berlin meaningless. If the Americans took the city, he felt, they would suffer up to 100,000 casualties and would then have to give up most of Berlin, and all the surrounding area, to the Russians anyway. Besides, he argued, there was no possibility of getting large Allied forces into Berlin before the Russians took the city. Once again, the alliance was greatly strained, but Eisenhower held it together even while insisting on his own views. He sent his forces into southern Germany. His decision remains the subject of hot dispute.

The Germans signed the unconditional surrender document on May 8, 1945. Eisenhower headed the occupation forces for six months, then went to Washington to succeed Marshall as chief of staff. He presided over the demobilization of the American Army, made speeches urging national defense, and wrote an account of his war career. Although pressed by both major parties to accept a presidential nomination, he insisted that he had no interest in politics and instead in 1949 accepted the presidency of Columbia University. In 1950 he left Columbia to become supreme commander of the newly formed North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces.

PRESIDENCY

Prominent Democrats had tried unsuccessfully to draft Eisenhower for the presidency in 1948. After he became NATO commander, representatives of both parties continued to query him about his availability for 1952. Their interest was due to his widespread popularity and aloofness from partisan strife. Eisenhower was reluctant to enter politics unless he was drafted. The Democrats could have met his conditions and given him a virtually uncontested nomination. Yet he chose to declare that he was a Republican because he believed that Democratic policies were promoting centralized government at the expense of individual liberty. However, Sen. Robert A. Taft of Ohio cherished the same conviction and believed that he had a better claim on the Republican presidential nomination. Taft headed a Midwestern faction strongly represented in Congress. It opposed lavish welfare programs at home. It was generally for retrenchment of American commitments abroad and critical of the Truman administration for aiding Europe at the expense of Asia. Although strongly nationalistic, the Taft faction preferred to fight communism by weeding out American subversives than by containment overseas. So it supported the demagogic investigations of Joseph R. Mc-Carthy of Wisconsin, a Republican. In short, it wanted to make an all-out fight on President Truman’s Fair Deal and believed that the Republicans had lost the last three presidential elections by soft-pedaling major issues.

1952 Nomination and Election.

Eisenhower preferred not to become a factional candidate, but the moderate Eastern wing of the party headed by Gov. Thomas E. Dewey of New York and Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., of Massachusetts persuaded him to announce his availability for the nomination. It soon became apparent that the Taft forces were strong enough to prevent a draft. So Eisenhower resigned as supreme commander and returned to tire United States on June 1, 1952, to wage a hectic five-week pre-convention campaign. The Taft and Eisenhower forces were so evenly matched that the outcome depended on the decision of some 300 delegates pledged to favorite-son candidates. In the end, they coalesced behind Eisenhower, and helped unseat contested Taft delegates from three Southern states. Eisenhower was nominated by a narrow margin on the first ballot. A number of delegates who voted for him would have preferred Taft but did not think the latter could win in November. The same reasoning led them to support a moderate platform.

Many Taft supporters were bitter over the outcome, but they eventually rallied to Eisenhower. His selection of Sen. Richard M. Nixon of California as his running mate helped to restore harmony because Nixon was conspicuously identified with congressional investigations of Communists. Using the new medium of television effectively, Eisenhower turned the ensuing campaign into a triumphal procession. Large, enthusiastic crowds greeted him everywhere and applauded his appeals for patriotism and clean government. Neither his jerky delivery nor his failure to deal with controversial issues checked the Eisenhower tide. He easily defeated his Democratic opponent, Gov. Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois, piling up a margin of 442 votes to 89 in the electoral college. In the popular vote, Eisenhower led Stevenson 33,937,252 to 27,314,-992. The Republicans captured both Houses of Congress by narrow margins and made inroads in the hitherto Democratic South because of its opposition to Truman’s civil “rights program.

Eisenhower brought to the presidency both the assets and limitations of a military background: a talent for administrative efficiency qualified by a deficient background in national problems outside the sphere of foreign relations. He established a chain of command, delegated broad responsibility to subordinates, and freed himself to grapple with the larger issues. He also attempted to learn about race relations, economic questions, and the intricacies of partisan politics. Although his knowledge grew steadily in all three areas, it seldom prompted him to vigorous action. He sought consensus above all else, and shunned bold, controversial programs. This tendency was reinforced by his belief that many problems would be better solved at the local level than through initiatives from Washington. Recause he admired businessmen and relied heavily on them in staffing his administration, Eisenhower was exposed to little dissent from his advisers.

Domestic Issues, First Term.

The initial domestic objectives of the new administration were to balance the budget, reduce the agricultural surplus by lowering price supports for farm products, and institute a loyalty program that would discourage the investigations of Senator McCarthy. Apart from Eisenhower’s inexperience, other obstacles impeded his efforts. Groups accustomed to receiving financial aid from the federal government opposed the reduction of government expenditures, and Congress was reluctant to offend them. Farmers wanted to grow as much as they pleased while retaining high price supports. Worse still, factional differences paralyzed the small Republican majorities in both Houses of Congress. Control rested with the Taft faction. Taft had tried to cooperate with Eisenhower, but he soon died. Thereafter, congressional leadership was more obstructive.

As a result, it took Eisenhower three years to balance the budget, and his victory was illusory because mounting expenditures for foreign aid and defense soon produced a new deficit. He also secured a token cut in support prices for agriculture. At first his cautious efforts to outflank McCarthy were fruitless, but McCarthy overreached himself in 1954, was censured by the Senate, and lost his influence. Meanwhile, a mild economic recession had begun, and many people blamed the monetary policies of George M. Humphrey, the conservative secretary of the treasury.

The Supreme Court confronted Eisenhower with another problem in May 1954 by declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. It set no time schedule for compliance. Most Northern Negroes customarily voted Democratic, and Eisenhower might have converted some by pressing energetically for implementation of the court order. But he temporized, partly because he was fearful of arresting the movement of Southern Democrats into the Republican party.

The Republicans lost both houses in the off-year congressional elections of 1954, but by such slim margins that the outcome could not be interpreted as a rebuke to the President. The sequel was a period of dead-center government in which the Democratic leadership subjected Eisenhower to pinpricks. Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson and House Speaker Sam Rayburn seldom challenged the President personally, but these skilled legislative leaders frequently outmaneuvered Eisenhower. On some issues, however, the Democrats supported Eisenhower in greater numbers than conservative Republicans. However, Eisenhower’s mild proposals for a commission to study racial discrimination and for federal aid to education were killed by Southern Democrats. Because neither Eisenhower nor the bulk of the voters seemed interested in innovation, the deadlock caused little visible indignation.

Foreign Affairs, First Term.

Eisenhower launched his administration with high hopes of ending the Cold War. Fulfilling a campaign pledge, the President-elect went to Korea in December 1952 to examine the military and diplomatic stalemate. After his inauguration, he quickly halted the fighting in Korea, but the negotiation of a cease-fire was the prelude to an uneasy truce rather than a genuine peace. He was more successful in securing the termination of the four-power occupation of Austria and the restoration of Austrian sovereignty in 1955. More comprehensive efforts to ease tension between the United States and the Soviet Union were less productive. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who favored a firm stand against communism, strongly influenced the President.

The administration promised to assume the diplomatic offensive and thereby free oppressed peoples behind the “iron curtain.” The “new look” in foreign policy involved an intensification of ideological activity. There was more rhetoric than action, notably in the case of Hungary’s abortive revolt against its Communist leaders.

Fresh hope for a détente revived in 1955 .when the Russians agreed to a Big Four meeting at Geneva in July. Eisenhower, meeting with the leaders of the Soviet Union, Britain, and France, created the most excitement with an offer to permit aerial inspection of the United States by Russian planes if the Soviet Union would reciprocate. The Soviet delegates treated this and other proposals with respect, but at a subsequent meeting of foreign ministers in October 1955 it became apparent that the two sides were as far apart as ever on substantive issues.

Shortly thereafter the USSR began to arm Egypt, which was engaged in an undeclared war with Israel. The next year, after the United States had declined to finance a huge dam at Aswan on the Nile River, Egypt accepted a Soviet offer to do so. Egypt soon nationalized the Suez Canal, and on Oct. 29, 1956, England, France, and Israel attacked Egypt. With the Eisenhower administration refusing to support its own Allies and the Soviet Union championing the Egyptians, the invasion was quickly called off. The subsequent effort of the President to serve as an honest broker led to the restoration of a shaky peace, but the episode was the prelude to further Soviet penetration of the Middle East.

Reelection in 1956.

The expectation that Eisenhower would run for a second term was shaken when he suffered a heart attack in September 1955 while vacationing in Colorado. He recovered slowly, but by February 1956 felt well enough to announce his candidacy. Although an operation for ileitis in June 1956 raised fresh doubts about his political future, Eisenhower was again in good health by convention time. ( He would also suffer a mild stroke in 1957, but it impaired his strength only briefly.) Yet uncertainty about his ability to survive a second term generated a movement to drop Vice President Nixon from the ticket in 1956 on the ground that he was an abrasive personality and would offend independent voters. Eisenhower did not encourage the dissidents, and Nixon was easily renominated.

The Democrats again selected Adlai Stevenson as their standard-bearer. The campaign was unusually free of issues. Eisenhower retained his image as a selfless public servant and confined his activities to nonpartisan appeals for support. The Democrats were afraid to attack him personally or to express direct doubts about his health. So they pictured the President as an amiable, naïve front man for Nixon and other “Red baiters.” Voters were supposed to conclude that McCarthyism would be revived if the President died in office. These tactics failed. Eisenhower won 41 states and 457 electoral votes, while Stevenson won only 7 states and 73 electoral votes. In the popular vote, Eisenhower led Stevenson 35,589,477 to 26,035,504. Unfortunately for the Republicans, Eisenhower was far more popular than his party, which was unable to regain control of either house of Congress.

Domestic Issues, Second Term.

Presidents seldom look as good in their second term as in their first, and Eisenhower was no exception to the rule. He struggled to maintain friendly personal relations with the Democratic leaders in Congress and largely succeeded. But his cordiality did not prevent them from ignoring some presidential recommendations and amending others. Mindful of his impending retirement and his decreasing ability to retaliate effectively, many Republican congressmen also became obstructive. This unstable coalition spearheaded a drive to increase the scope of welfare programs. Recognizing that he was unable to reduce governmental activities, Eisenhower fought to prevent them from getting larger. He was also embarrassed by congressional investigations of executive departments. The major casualty was Sherman Adams, his chief assistant and an influential adviser, who was forced to resign because he had accepted gifts from a textile manufacturer and lobbyist.

During his second term, Eisenhower also faced increasing repercussions from the 1954 school desegregation decision of the Supreme Court. Inclined to take the legally defensible but morally dubious position of acquiescing in delaying tactics, Eisenhower was obliged to act when a Southern mob obstructed token integration of a high school in Little Rock, Ark., in 1957. His initial efforts to get state authorities to enforce a federal court order were fruitless. So he dispatched military units to Little Rock and secured compliance with bayonets. The sullen attitude of local whites discouraged Eisenhower from further efforts at integration either by coercion or any other method. The adverse effect of his indecisiveness on Negroes was compounded by the tactics of Republican senators, many of whom voted with Southern Democrats to retain the rules permitting filibusters against civil rights legislation. Civil rights acts passed in 1957 and 1960 dealt rather ineffectively with voting rights.

Neither the Negroes nor any other discontented group were inclined to support the Republicans when Eisenhower’s magical name did not head the ticket. The GOP, also handicapped by a recession, suffered a disastrous defeat in the 1958 congressional elections as the Democrats sharply increased majorities in both the Senate and the House.

Foreign Affairs, Second Term.

Eisenhower also encountered increasing frustration after 1957 in his attempts to moderate the Cold War. After a left-wing revolution in Iraq, Eisenhower airlifted a marine detachment to Lebanon in 1958 to forestall a similar uprising there. The immediate crisis soon subsided, and the troops were withdrawn, but the American position in the Middle East continued to deteriorate. In the same year, Vice President Nixon was almost killed by a hostile mob in Caracas, Venezuela, during a goodwill tour. Anti-American feeling erupted still closer to home when the radical Fidel Castro seized power in Cuba. Eisenhower outwardly ignored Castro’s increasingly strident attacks on the United States but was criticized for both provoking and tolerating them.

Ill-fortune likewise dogged Eisenhower’s final bid for an accommodation with the Russians. Premier Nikita Khrushchev boycotted a projected summit conference at Paris in May 1960. Krushchev’s excuse was the shooting down of an American U-2 plane that had been photographing installations in the USSR. Democrats criticized Eisenhower for jeopardizing peace with spy missions. They also charged that the administration was falling behind the Soviet Union in the development of missiles and other weapons of the space age. The secrecy that shrouded military planning precludes an objective judgment about Eisenhower’s stewardship in that area. He did voicc concern about the growing power of the Pentagon and of the “military-industrial complex.” In any case, the combination of setbacks and partisan complaints about the administration’s foreign policy were politically damaging on the eve of the 1960 election.

The 1960 Election.

Long before the Republican convention, Eisenhower had groomed Nixon as his successor, giving the Vice President special assignments designed to command favorable publicity. The delegates enthusiastically ratified the choice. The Democrats nominated John F. Kennedy, the youthful Catholic senator from Massachusetts, who combined an appealing personal style with an eloquent updating of New Deal doctrines. Fearful that Eisenhower would unintentionally divert the spotlight from his protégé, Nixon’s managers limited presidential participation in the campaign to the final weeks. Eisenhower’s impact on Republican prospects was favorable but might have been greater had he been encouraged to intervene earlier. Kennedy reunited a large enough percentage of each group in the old New Deal coalition to win the election. ‘ Eisenhower transferred enough of his Democratic and independent support to Nixon to produce a close contest. Like the popular Whig generals of the 1840’s, Eisenhower could win elections, but he could not convert personal loyalty into durable support for his party.

RETIREMENT

During the initial years of his retirement, Eisenhower was healthy, active, and the recipient of many honors. Congress restored his rank as a five-star general, colleges conferred honorary degrees on him, and private organizations showered him with awards. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson treated him as an elder statesman, frequently soliciting his advice on international problems. These friendly relations survived Eisenhower’s occasional attacks on Democratic policies and his efforts to rebuild the Republican party. He also established a repository for his papers at Abilene, Kans., and worked on his memoirs. When not traveling, he resided either on his farm at Gettysburg, Pa., or in the vicinity of Palm Springs, Calif. His recreational activities

were concentrated on golf, hunting, fishing, and painting.

Eisenhower did not endorse any candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in 1964, but encouraged a number whom he regarded as qualified to enter the race. He was disappointed when the delegates selected Sen. Barry M. Goldwater of Arizona because he thought the candidate was identified with an intemperate brand of conservatism. Eisenhower eventually endorsed Goldwater without becoming an active supporter.

A serious heart attack in August 1965 ended Eisenhower’s active participation in public affairs. He was hospitalized frequently with a variety of complaints during the next three years and was an invalid after still another heart attack in the summer of 1968. Nevertheless, he endorsed Nixon for president and was gratified by his subsequent victory. His popularity never waned, and he topped the list of most admired Americans in a Gallup poll released in December 1968. Eisenhower died in Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, D. C., on March 28, 1969, and was buried at Abilene, Kans.

mavi