Who Is Pablo Picasso? The life story of Pablo Picasso. Information on Pablo Picasso biography, works, art and paintings.

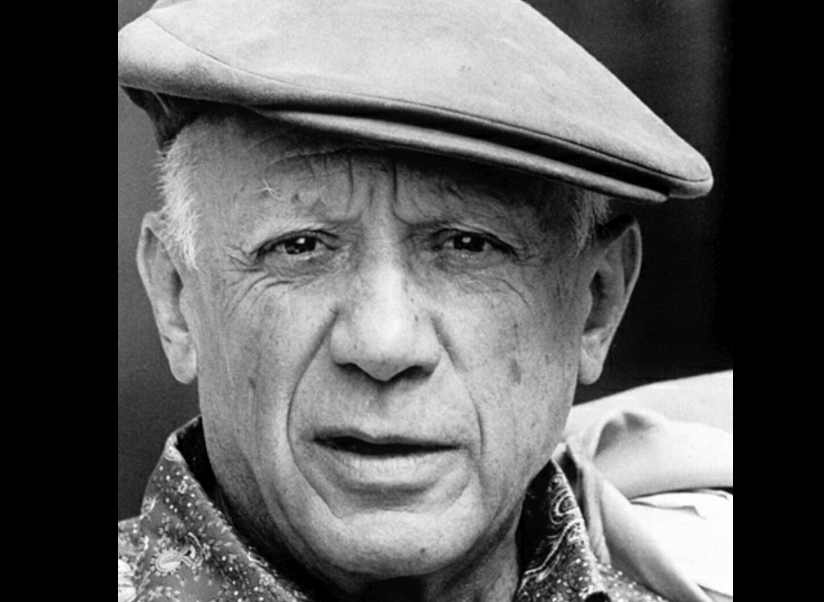

Pablo Picasso; (1881-1973), Spanish-born painter, sculptor, and printmaker, who is considered the greatest artist of his time. His name is inseparable from 20th century art, a period he filled out through a production of more than seven decades in a variety of media. In each of them he probed formal possibilities, invented images, and reflected underlying realities of the age. In so doing, he, no less than the finest thinkers, explorers, and scientists, helped to shape the 20th century world.

Early Years (1881-1904).

Picasso was born on Oct. 25, 1881, in Málaga, on the south coast of Spain, to José Ruiz Blasco and his wife, Maria Picasso López. From 1901, Pablo used only the more glamorous, faintly exotic maternal name “Picasso” as his signature.

Don José, an art teacher, moved his family first to the Atlantic port of La Coruña and then, in 1895, to Barcelona, capital of Catalonia, where he was a professor at the School of Fine Arts. In 1895 his son passed the school entrance examinations in record time, enrolling at age 14. Two years later he went to Madrid to study at the Royal Academy. But he soon returned to the lively Catalonian capital and the intellectual stimulation at Els Quatre Gats, the inn where poets, artists, and critics met to exchange ideas drawn from the big world outside Spain.

Source : wikipedia.org

Although Picasso formed valuable, long lasting friendships in Barcelona and Madrid, neither city could satisfy for long his eager curiosity. In 1904, after four difficult years divided among Paris, Barcelona, and Madrid, Picasso left Spain to settle permanently in Paris.

Imitative Styles.

Picasso drew and painted from childhood on. In his early teens he worked under his father’s influence in the conventional tradition of Spanish realism. As his subject matter broadened, Picasso’s youthful imitative modes included the dotted style of impressionism and the sinuous idiom of art nouveau, which was probably known to him through the work of the Swiss poster maker T. A. Steinlen and the French postim-pressionist Toulouse-Lautrec, but more directly through Isidre Nonell, his gifted, older painter friend from Barcelona.

Probably the first important Parisian painting by Picasso, then 19, is Le Moulin de la Galette (1900; Guggenheim Museum, New York). It depicts a dim, gaslit café, where men in top hats dance with women of the demimonde, as others stand or sit in postures of seductive intimacy.

Blue Period.

Mood and pathos expressed through figures of beggars, cripples, harlots, and other outcasts mark Picasso’s earliest Parisian style from the end of 1901 through 1904. Blue is the prevalent color of such works as The Blue Room (1901; Phillips Collection, Washington) and Old Guitarist (1903; Art Institute of Chicago)—a reflection, perhaps, both of a personal state of mind and a pessimistic, fin-de-siècle sentiment. Despite some early support from such venturesome dealers as Berthe Weill and Ambroise Vollard and the encouraging friendship of the writer Max Jacob, Picasso at that time suffered extreme poverty, hunger, and cold. It was, therefore, an act of real courage when, undeterred by this inhospitable reception, he determined to settle in Paris, the art capital of the world.

Years Before World War I (1904-1914).

The period beginning with Picasso’s permanent residence in Paris and ending with the outbreak of World War I encompasses the artist’s most significant contributions to art. The early masterpieces of the Rose Period and the creation of cubism both fall within this heroic decade of his life.

In 1904, Picasso took up residence in the Bateau Lavoir, a rickety building in Montmartre named for the laundry barges on the Seine. There he lived for the next five years in material poverty and spiritual elation. Besides Max Jacob, he made friends with the Americans Gertrude and Leo Stein, the poet-critic Guillaume Apollinaire, and his neighbor Fernande Olivier, the first among many famous mistresses whose features animated Picasso’s work. Most important was Picasso’s friendship with Georges Braque, with whom a few years later he initiated the cubist style, thereby launching the most radical departure in 20th century art.

Rose Period.

Toward the end of 1904, the moody and sometimes sentimental melancholy of the Blue Period gave way to predominantly earthen, brown, and pink hues, as Picasso’s figurative subjects moved from the city’s cafés and bistros into the roads and the countryside. Picasso now came to see his beggars, circus folk, and street singers with a measure of detachment, rendering these subjects less self-consciously and more objectively.

The most impressive summary of this new, lightly colored style is The Family of Saltimbanques (1905; National Gallery, Washington), in which the members of a circus clan seem to look past one another. Clad in circus dress and rags, carrying accessories of their trade, they are placed in a sparse landscape that emphasizes their loneliness. In such paintings as Self Portrait (1906; Philadelphia Museum of Art) and Two Nudes (1906; Museum of Modern Art, New York) the sense of detachment increases together with three-dimensional, sculptural attributes that accommodate themselves in a shallow picture space.

Toward Cubism.

Picasso’s development toward cubism reached its climax with the monumental, justly celebrated Demoiselles d’Avignon ( 1906-1907; Museum of Modern Art). This painting, named for a brothel in Barcelona’s Avignon Street, depicts, in highly stylized form, five angular nude or partially draped women grouped around an arrangement of fruit. This final, condensed version, developed through many preparatory works, was attained by gradual simplifications and eliminations of an originally conspicuous, allegorical subject matter.

Picasso’s manifold visual inheritance, including El Greco and Iberian and probably African sculpture, as well as the rich legacy of Cézanne, is contained and absorbed within this grand recapitulation of all his previous strivings. At the same time, the painting may be seen as a point of departure for the subsequent cubist reformation. The formal innovations of Les Demoiselles contain the basic vocabulary of cubism.

Painting, the medium Picasso explored for more than 70 years, provides the only means of continuously tracing his style. Sculpture, occurring more sporadically, offers an occasional parallel to painting. His style was also revealed in his book illustrations and other graphics, especially from the 1930’s on.

Source : wikipedia.org

Cubism.

By 1909, Picasso had established himself as a painter of exceptional talent in Paris and abroad. Leaving behind the picturesque poverty of the Bateau Lavoir, he moved to more comfortable quarters in the Boulevard de Clichy. He took summer vacations in Spain and Provence, and he replaced Fernande in his affections with her friend Marcelle Humbert, whom he called Eva.

In 1910, Picasso’s cubist style reached full maturity. In Portrait of Kahnweiler (1910; Art Institute of Chicago), a painting of his dealer and friend Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Picasso reduces the subject to vestigial remnants that appear in danger of disintegrating into a formal scaffolding. Meaning in such works, whether paintings, drawings, prints, or sculptures, must be sought in the conjugation of forms—until 1911 through analytical dissection and, thereafter, through synthetic reconstructions.

In the earlier analytical phase, to which the Kahnweiler portrait belongs, figurative imagery and color are reduced in favor of structure. In the later synthetic phase, modified formal developments are employed with the addition of color and an expansion of iconography. Synthetic cubism grows out of paper pasting, or “collage,” in which common, commercial materials, such as wallpaper, cloth, or newspaper, simultaneously enrich and adulterate the pure cubist form. Still Life with Chair Caning (1911-1912; Picasso Collection), combining oil paint and printed oilcloth, exemplifies Picasso’s delight in making reality and illusion confront each other in their ever elusive relationship.

Picasso also explored cubism in sculpture. Besides examples of analytical cubism, he created such masterpieces as the synthetic construction Guitar (1912; Museum of Modern Art). The severe beauty of such constructions was superseded by colorful and intimate “rococo” variants of cubism, such as the gemlike sculpture Glass of Absinthe (1914; Museum of Modern Art).

War Years and Interim (1914-1944).

The outbreak of World War I tore the fabric of Picasso’s Parisian world. Braque joined the army in 1914, and their eminently fruitful friendship was never renewed. Apollinaire, likewise a soldier, died in an influenza epidemic. Also, Eva died in 1915. Picasso, having previously moved from Mont-martre to Montparnasse, took a small house in Montrouge in 1916.

Realism.

Despite these upheavals, the war years were productive for Picasso and brought important stylistic changes, especially an apparent return to realism, as seen in a pencil drawing of 1915, Portrait of Vollard (Metropolitan, New York). The likeness of Ambroise Vollard, Picasso’s early dealer, is rendered with a precision meticulous enough to match Ingres’ 19th century draftsmanship. This small work, more than any other, foretells Picasso’s renewed interest in descriptive rendition, which for some time ran parallel with cubism. Influenced by Greco-Roman sources, Picasso worked in mannerist and neoclassical styles. This development kept abreast of his synthetic cubist phase that achieved such masterpieces as the two versions of the Three Musicians (1921; Philadelphia Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art).

Picasso’s realist development was reinforced by stage design commissions resulting from an encounter during wartime with Serge Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes. With the help of assistants, Picasso painted a neoclassical fantasy of circus figures on a large curtain for the spectacular ballet Parade (1917).

Parade and other Diaghilev productions also led to new friendships with writers, musicians, and artists linked with Dada and the subsequent surrealist movement. Besides the Dadaist leader Tristan Tzara and the surrealist spokesman André Breton, Picasso met the poets Jean Cocteau, Paul Éluard, and Louis Aragon; the composers Erik Satie and Igor Stravinsky; and many artists, including Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Joan Miré, and Man Ray. Paul Rosenberg became his dealer, and in 1918, Picassp married a young Russian dancer, Olga Koklova. Much travel, an increasingly social life-style, and the establishment of the Picassos in a large apartment in the Rue de la Boétie characterized these years.

Source : wikipedia.org

Surrealism.

During the 1920’s a growing sense of unease is reflected in Picasso’s work. There was a change in emphasis from constructed to expressive form and from a style predominantly cubist to one closer to surrealism, although Picasso never formally joined the movement. The clearest revelation of such changes is Three Dancers (1925; Tate Gallery, London), depicting three attenuated female figures engaged in a frenetic dance. The underlying cubist structure is used toward expressive ends, and the work thus becomes a forerunner of a convulsive imagery that later reached its dramatic climax in 1937, in the tortured Guernica.

Other paintings of the late 1920’s and early 1930’s include increasingly distorted, surrealist figures, such as Woman in an Armchair ( 1929; Picasso Collection), Seated Bather (1930; Museum of Modern Art), and still lifes. Sculpture of this period includes metamorphic bronze figures ( and related drawings ), geometric constructions of iron rods and sheet metal influenced by the sculptor Julio Gonzales, large plaster figures of man and beast, and ingenious assemblages of man-made objects with surrealist overtones. His prolific graphic works include series of etchings illustrating Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1931), Aristophanes’ Lysistrata ( 1934 ), and the theme of the sculptor’s studio ( 1933 ).

The strained attenuations in many of Picasso’s works of this period may, in part, be read as a reflection of personal crisis. His domestic life reached an impasse, which in the mid-1930’s led to a drastic reduction of his painting activities. The failure of his marriage and subsequent separation from the conventional Olga in 1935 was bracketed by liaisons with the sensual blond model Marie Thérèse Walter in the early 1930’s and later with the aloof aristocratic photographer Dora Maar. Their features inhabit much of Picasso’s work, such as Girl Before a Mirror (1932; Museum of Modern Art) and Woman Weeping ( 1937; Sir Roland Penrose Collection, London).

Expression of Historical Crisis.

In the 1930s, Picasso’s surrealist images became more overtly symbolic, and his private allegories simultaneously bespoke not only his personal emotional turmoil but also the tragic political events of the time. The Spanish Civil War of 1936 generated a patriotism and a humanitarian outrage expressed in the series of etchings The Dream and the Lie of Franco ( 1937 ) and in Guernica, the mural allegory portraying the Spanish town bombed by Franco’s forces, which became a byword of victimization through senseless destruction.

In both the Franco series and Guernica, Picasso falls back upon the bullfight imagery that had captivated him intermittently throughout his life ana that he had employed with fresh conviction in his masterful etching Minotauromachy ( 1935 ). The protagonists of the latter—the bull of brute strength, the horse in death agony, the woman as fallen matador, and the girl holding a light—reappear transformed in Guernica and in its extensive cycle of fragments, sketches, and versions in various media. An unsurpassable expression of violence, Guernica may well be the most intense plastic creation of its time. On loan to the Museum of Modern Art, it was directed by Picasso to be taken to Spain when that country should become a republic.

Two years after Guernica was completed, all Europe was engulfed in war. Picasso was enclosed in his studio in the Rue des Grandes Augustines in Paris, to which he had moved after hiding his work near Bordeaux.

Postwar Years (1944-1973).

The liberation of Paris in 1944 found Picasso well and hard at work, casting that year Man with a Lamb, a powerful bronze evoking Archaic Greek sculpture. His effective passive resistance against the Germans, combined with his now universal fame, greatly enhanced his public stature. In a gesture of naive idealism, he joined the Communist party in 1944. His lithograph of a dove, used on a poster, became a symbol of leftist peace movements.

Gradually, however, Picasso withdrew both from public activity and from Paris, spending ever more time in the south of France. In the company of the young painter Françoise Gilot, he moved first to Antibes in 1946 and then in 1948 to the pottery town Vallauris. There he undertook large-scale production of painted pottery and modeled figures and executed the murals War and Peace ( 1952 ) in a deconsecrated 12th century chapel. Paintings of this period include the lighthearted Joie de Vivre ( 1946; Musée Grimal-di, Antibes), as well as many portraits of Françoise.

In 1953, Françoise left Picasso, and that year Jacqueline Roque, cousin of a Vallauris potter, became the last of the women who inspired the artist. They moved from villa to villa, in Cannes and in the vicinity of Aix-en-Provence. Olga, who had never divorced Picasso, had died in 1955, and in 1961 he married Jacqueline. They finally settled in Mougins, in the mountains north of Cannes.

The ever-robust, energetic Picasso continued an undiminished working life. But in these later years the radical innovations of his youth and middle age gave way to detached, self-mocking images, in such recurring themes as the aging artist and young model. Drawing upon reserves stocked up in a lifetime of formal search, Picasso increasingly turned toward the past, to interpret Delacroix, Velazquez, and Manet in his own terms. When, close to 92, he died in Mougins on April 8, 1973, the world, almost forgetful of his radicalism, acknowledged and mourned him as the last of the great masters.