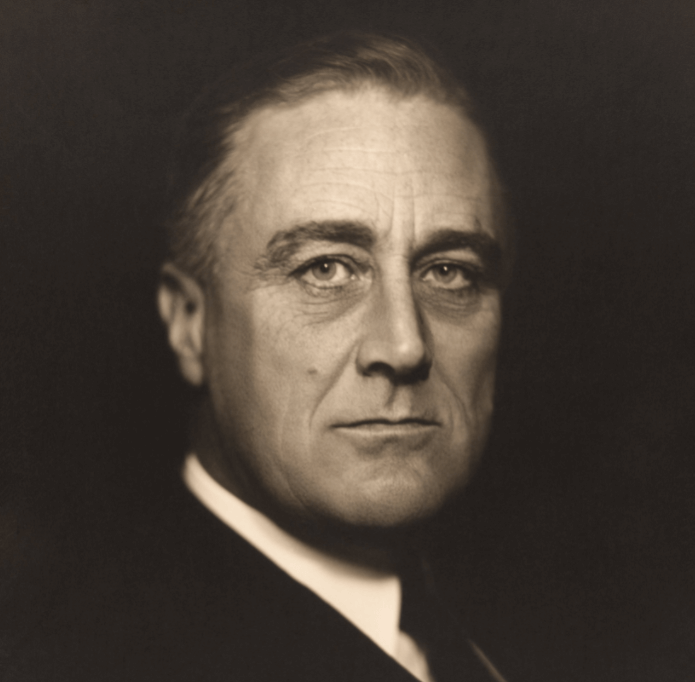

What is the detailed life story, biography of Franklin Delano Roosevelt? Information on Franklin Delano Roosevelt youth, career, presidency and death.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt; (1882-1945), 32nd president of the United States. Roosevelt became president in March 1933 at the depth of the Great Depression, was reelected for an unprecedented three more terms, and died in office in April 1945, less than a month before the surrender of Germany in World War II. Despite an attack of poliomyelitis, which paralyzed his legs in 1921, he was a charismatic optimist whose confidence helped sustain the American people during the strains of economic crisis and world war.

He was one of America’s most controversial leaders. Conservatives claimed that he undermined states’ rights and individual liberty. Leftists found him timid and conventional in attacking the Depression, Others thought him devious and inconsistent and uninformed about economics. Some of these claims were well founded. Though Roosevelt labored hard to end the Depression, he had limited success. It was not until 1939 and 1940, with the onset of heavy defense spending before World War II, that prosperity returned. Roosevelt also displayed limitations in his handling of foreign policy. In the 1930’s he was slow to warn against the menace of fascism, and during the war he relied too heavily on his charm and personality in the conduct of diplomacy.

Still, Roosevelt’s historical reputation is deservedly high. In attacking the Great Depression he did much to develop a partial welfare state in the United States and to make the federal government an agent of social and economic reform. His administration indirectly encouraged the rise of organized labor and greatly invigorated the Democratic party. His foreign policies, while occasionally devious, were shrewd enough to sustain domestic unity and the allied coalition in World War II. Roosevelt was a president of stature.

YOUTH AND EARLY CAREER

The future president was born on Jan. 30, 1882, at the family estate in Hyde Park, N. Y. His father, James (1828-1900), was descended from Nicholas Roosevelt, whose father had emigrated from Holland to New Amsterdam in the 1640’s. One of Nicholas’ two sons, Johannes, fathered the line that ultimately produced President Theodore Roosevelt. The other son, Jacobus, was Tames’ great-great-grandfather.

James graduated from Union College (1847) and Harvard Law School, married, had a son, and took over his family’s extensive holdings in coal and transportation. Despite substantial losses in speculative ventures, he remained wealthy enough to journey by private railroad car, to live graciously on his Hudson River estate at Hyde Park, and to travel extensively.

Four years after his first wife died in 1876, James met and married Sara Delano, a sixth cousin. She, too, was a member of the Hudson River aristocracy. Her father, one of James’ business associates, had made and lost fortunes in the China trade before settling with his wife and 11 children on the west bank of the Hudson. Sara had sailed to China as a girl, attended school abroad, and moved in high social circles in London and Paris. Though only half her husband’s age of 52 at the time of her marriage in 1880, she settled in happily at Hyde Park. Their marriage was serene until broken by James’ death in 1900.

Young Franklin had a secure and idyllic childhood. His half-brother was an adult when Franklin was born, and Franklin faced no rivals for the love of his parents, who kept him in dresses and long curls until he was five, and in kilts and Little Lord Fauntleroy suits for several years thereafter. Summers he went with his parents to Europe, to the seaside in New England, or to Campobello Island off the coast of New Brunswick, where he developed a love for sailing. Until he was 14 he received his schooling from governesses and private tutors.

Franklin’s most lasting educational experience was at Groton School in Massachusetts, which he attended between 1896 and 1900. Groton’s headmaster, the Rev. Endicott Peabody, was an autocratic yet inspiring leader who instilled Christian ethics and the virtues of public service into his students, most of whom were of the privileged classes. Franklin’s academic record at Groton was undistinguished, and he did not excel at sports. Some of his classmates, finding him priggish and superficial, called him the “feather-duster.” But for a boy who had been so resolutely sheltered by his parents, he was popular enough. At Groton, Franklin revealed that he could adapt himself readily to different circumstances. The Groton years also left him with a belief, more manifest later, that children of the upper classes had a duty to society.

Source : pixabay.com

His record at Harvard, which he attended between 1900 and 1904, was only slightly more impressive. Thanks to his excellent preparation at Groton, he was able to complete his course of study for his B. A. in 1903, in only three years. During his fourth year he served as editor of the Crimson, the college newspaper. However, he was not accepted for Porcellian, Harvard’s most prestigious social club, and he did not receive much stimulation in the classroom. As at Groton, his grades were mediocre, and he showed rio excitement about his studies.

Personal Life.

While at Harvard, Franklin fell in love with Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, his fifth cousin once removed. Eleanor had had a trying childhood. Her mother, a beautiful socialite who gave her little affection, died when Eleanor was eight. Her father, Theodore Roosevelt’s brother, was spirited and charming. But he was unstable and alcoholic, and he died when Eleanor was ten. Orphaned, she lived with her maternal grandmother and entered her teens feeling rejected, ugly, and ill at ease in society. When Franklin, a dashing Harvard man two years her senior, paid her attention, she was flattered and receptive. On March 17, 1905, the two Roosevelts were married. Her uncle Theodore, president of the United States, gave her away.

The marriage was successful enough on the surface. Within the next 11 years Eleanor delivered five children (a sixth died in infancy): Anna (1906), James (1907), Elliott (1910), Franklin D., Jr. (1914), and John (1916). Having been born into wealth, the Roosevelts never lacked for money, and Eleanor and Franklin moved easily among the upper classes in New York and Campobello. Eleanor, however, was often unhappy. For much of her married life she had to live near Franklin’s widowed and domineering mother. Family duties kept her at home, while Franklin played poker with friends or enjoyed the good life. Later, during World War I, she was staggered to discover that Franklin was having an affair with her social secretary, a pretty young Virginian named Lucy Mercer.

Despite these tensions, Eleanor remained a helpful mate throughout the 40 years of her marriage to Franklin. When he contracted polio in 1921, she labored hard to restore his emotional health and to encourage his political ambitions. Thereafter, with Franklin confined to braces and wheelchairs, she served as his eyes and ears. Because she possessed deep sympathy for the underprivileged, she goaded his social conscience.

For the first five years of their marriage the young Roosevelts lived in stately houses in New York City. Franklin attended law school at Columbia until the spring of 1907, when he quit, foregoing the degree, after passing the New York state bar examination. He then took a job with the Wall Street law firm of Carter, Ledyard, and Milburn. Much of the firm’s practice was in corporate law. Roosevelt found the work tedious, and chafed under the routine. By 1910 he was 28, restless, and unfulfilled.

State Senator.

At this point politics gave him a sense of purpose. The Democratic organization in Dutchess county, the area around Hyde Park, needed a candidate for the New York state Senate in 1910. Party leaders recognized that although Roosevelt had no political experience he had assets as a candidate: the wealth to finance a campaign, and the best-known political name in the United States. And though Franklin had voted for “TR,” a Republican, his father had been a Democrat. Franklin, who admired TR, knew that politics could be exciting and worthwhile. Anxious to escape the humdrum of law practice, he told the organization he would run.

Roosevelt worked as never before during the campaign. Acquiring a car, he crisscrossed the county in his quest for support. He showed skill at making himself agreeable to voters and a willingness to listen to the advice of political veterans. As at Groton and Harvard, during his political career he proved open and adaptable. Perhaps his greatest asset in the campaign was the national trend away from the Republican party, which was badly split in 1910. For all these reasons Roosevelt won impressively in the usually Republican district.

Roosevelt made an immediate impact in the legislative session of 1911. At that time U. S. senators from New York were elected by the legislature, not by popular vote. The Democrats, with majorities in both houses, prepared to select William F. Sheehan, a transportation and utilities magnate who was the choice of Tammany Hall, New York City’s powerful political machine. A few Democrats balked at the choice. Roosevelt joined them and became their leader.

His motives were idealistic. Reflecting TR’s faith in progressivism and in honest government, he distrusted the “bossism” of Tammany Hall. After a bitter struggle lasting almost three months, Tammany won a qualified victory by securing the insurgents’ acquiescence in the selection of Judge James A. O’Gorman, a former Tammany Grand Sachem, to the Senate. But Roosevelt and his allies took some consolation in having forced the withdrawal of Sheehan and in attracting nationwide attention. It was an auspicious start to a career in politics.

The young legislator’s demeanor during the struggle evoked mixed reactions. Progressive reformers liked his devotion to principle, his political courage, and his willingness to work hard. They welcomed his support of other contemporary reforms: soil conservation, state development of electric power, the direct primary, popular election of senators, and, by 1912, women’s suffrage, workmen’s compensation, and legislation setting a maximum workweek of 54 hours for boys 16 to 21 years old.

Nevertheless, party regulars like Alfred E. Smith, a majority leader in the Assembly, and Robert F. Wagner, Democratic leader in the Senate, considered Roosevelt something of a lightweight and headline-seeker. Other legislators disliked his manner. Still the patrician from Groton and Harvard, he had a habit of tossing up his head and looking down his nose at people. He later confessed, “You know, I was an awful mean cuss when I first went into politics.”

In 1912, Roosevelt defied Tammany again, this time by supporting Gov. Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey for the Democratic presidential nomination. After Wilson won the nomination, Roosevelt ran for reelection to the state Senate. Though he contracted typhoid fever during the campaign, he was helped to victory by Louis Howe, a bent, asthmatic newsman, who was to become his most loyal aide.

Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

Josephus Daniels, Wilson’s new secretary of the navy, then offered the successful young legislator a more attractive job, as assistant secretary. This was the post that TR had held 15 years earlier. It meant that FDR could deal with matters close to his heart: ships and the sea. Accepting Daniels’ offer, Roosevelt moved to Washington in 1913.

As assistant secretary (1913-1920), Franklin Roosevelt reminded many people of TR. He advocated a big Navy, preparedness, a strong presidency, and an active foreign policy. In 1917 he enthusiastically supported war against Germany, and in 1918 he took pleasure in visiting the front in Europe. Sometimes he clashed wi^h Daniels, a progressive with pacifist leanings. But Daniels was tolerant of his subordinate. The secretary appreciated Roosevelt’s dexterous handling of admirals, departmental employees, and labor unions, which were active in naval yards, and his opposition to the collusive bidding and price-fixing practiced by defense contractors. FDR’s years of service as assistant secretary gave him administrative experience and a host of contacts in Washington and the Democratic party.

During this period Roosevelt learned the wisdom of political compromise. His lesson came from harsh experience. In 1914 he challenged Tammany again by seeking the nomination for U. S. senator. Tammany responded by endorsing James Gerard, America’s ambassador to Germany. Gerard won overwhelmingly in the primary, 211,000 to 77,000, only to lose to a Republican in November. Thereafter Roosevelt refrained from battling Tammany, which gradually forgave and forgot. He also worked hard at making himself personally agreeable. By 1920, at 38, he had lost some of his earlier haughtiness. Handsome, exuberant, gregarious, he projected vitality and charm.

Vice-Presidential Nominee.

These qualities made him a popular choice for the Democratic vice-presidential nomination in 1920. Running with the governor of Ohio, James M. Cox, he supported progressive ideals and American participation in the League of Nations. He proved an energetic and well-received campaigner, slipping badly only once—when he bragged clumsily about writing the constitution of Haiti while in the Navy Department. His mistake made no difference in the outcome, which was foreordained amid the disillusion with President Wilson’s leadership in 1920. Cox and Roosevelt were beaten decisively by the Republican candidates, Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, in November.

Return to Private Life.

With the Republicans ascendant, Roosevelt had little choice but to return to private life. He formed a law firm in New York City and became vice president of Fidelity and Deposit Company of Maryland, a surety bonding firm.

Stricken with polio in August 1921, Roosevelt fought back under the care of Eleanor and Louis Howe. In 1924 he discovered the medicinal waters of Warm Springs in western Georgia. He hoped that they would relieve his paralysis, and he formed the Warm Springs Foundation for other polio victims and spent several months a year there for the rest of the decade. In 1924 he became president of the American Construction Council, a trade association that attempted vainly to bring order into the building business.

His primary interest remained politics. In 1924 he favorably impressed delegates to the Democratic national convention by making an eloquent (though futile) speech nominating for the presidency Alfred Smith, the “happy warrior” who had become governor of New York. Throughout the decade he widened his circle of contacts by stopping off in Washington on his way to and from Warm Springs, and by writing letters appealing for unity within his party, which was badly split along geographical and urban-rural lines. The Democratic party, he said, should stand for “progressivism with a brake on,” not “conservatism with a move on.”

Governor of New York.

In 1928, Roosevelt vaulted suddenly to national prominence. After helping Smith get the presidential nomination, he set off for Warm Springs, where he looked forward to weeks of therapy. But Smith urgently needed a strong gubernatorial candidate on the Democratic ticket in New York, and he pressured Roosevelt into running. Smith lost the election to Herbert Hoover, the Republican presidential candidate, who carried New York by 100,000 votes. Roosevelt, more popular upstate than Smith, successfully bridged the urban-rural gap in the Democratic party and beat his opponent, state Attorney General Albert Ottinger, by 25,000 votes. It was a striking triumph in an otherwise Republican year.

During his two terms, Governor Roosevelt battled a Republican legislature for many progressive measures. These included reforestation, state-supported old-age pensions and unemployment insurance, legislation regulating working hours for women and children, and public development of electric power. He named skilled people to important positions, including James Farley, a New York City contractor, as chairman of the state Democratic Committee; Frances Perkins, a social worker, as state industrial commissioner; and Samuel Rosenman, an able young lawyer, as his speech writer and counsel. All became important aides during Roosevelt’s presidency.

In 1931, when the Depression was serious, Roosevelt became the first governor to set up an effective state relief administration. Harry Hopkins, a social worker who later served as his closest adviser in Washington, directed it. In a series of “fireside chats” Governor Roosevelt also proved a persuasive speaker over the new medium of radio. He was reelected in 1930 by 750,000 votes, the largest margin in state history.

THE PRESIDENCY

While Roosevelt was governor of New York, the Great Depression tightened its grip on the country. Roosevelt, seeking new ideas, enlisted a “brains trust” of Columbia University professors to help him devise prografns against hard times. These professors included Rexford Tugwell, Raymond Moley, and Adolf Berle, Jr. All became leading figures in the national administration in 1933. Acting on their suggestions, Roosevelt stressed the need to assist the “forgotten man.” He added that “the country demands bold, persistent experimentation.” Meanwhile, Farley and other supporters were lining up delegates for Roosevelt throughout the country. By the time the Democratic national convention opened in Chicago in June 1932, Roosevelt stood out as the most dynamic and imaginative contender for the presidential nomination.

Despite these assets, FDR faced formidable opposition at the convention, from House Speaker John Nance Garner of Texas; former Secretary of War Newton D. Baker of Ohio, a potential compromise choice; and former Governor Smith, who still cherished ambitions of his own. For three ballots Roosevelt held a large lead, but lacked the two-thirds margin necessary for victory. Farley then promised Garner the vice-presidential nomination. The move succeeded. Garner reluctantly accepted the vice presidency, and FDR took the presidential nomination on the fourth ballot.

Most party leaders applauded the Roosevelt-Garner ticket, which closed the heretofore fatal gulf between the urban-Eastern and rural-Southern-Western wings of the party. They responded especially to Roosevelt, who broke with precedent to fly to the convention and to tell the delegates, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.”

Source : wikipedia.org

The 1932 Campaign.

During the fall campaign against President Hoover, Roosevelt suggested a few parts of this “new deal.” He supported spending for relief and public works. He favored some plan, undefined, to curb the agricultural overproduction that was depressing farm prices. He spoke for conservation, public power, old-age pensions and unemployment insurance, repeal of prohibition, and regulation of the stock exchange.

Otherwise, he was vague. He said little about his plans for industrial recovery or about labor legislation, and he was fuzzy about foreign policy and the tariff. On some occasions he promised to support increased expenditures for relief; on others he denounced the Hoover administration for extravagance.

FDR’s equivocations on these issues alienated some intellectuals and reformers, who turned to the Communist or Socialist party on election day. But for most Americans, including the majority of progressives, Roosevelt seemed the only viable alternative to Hoover, who many people blamed unfairly for the Depression. On election day Roosevelt captured 22,821,857 votes to Hoover’s 15,761,841, and took the Electoral College 472 to 59. The voters sent large Democratic majorities to both houses of Congress.

The New Deal.

By March 4, 1933, when Roosevelt was inaugurated at the age of 51, the economic situation was desperate. Between 13 and 15 million Americans were unemployed. Of these, between 1 and 2 million persons were wandering about the country looking for jobs. Hundreds of thousands squatted in tents or ramshackle dwellings in “Hoovervilles,” makeshift villages on the outskirts of cities. Panic-stricken people hoping to rescue their deposits had forced 38 states to close their banks.

From the beginning, Roosevelt tried to restore popular confidence. “The only thing we have to fear,” he said in his inaugural address, “is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror.” He added that he would not stand by and watch the Depression deepen. If necessary, he would “ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis—broad executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.” He then closed the rest of the banks—declaring a “bank holiday”—and called Congress into special session.

His first legislative requests were conservative. He began by securing passage of an emergency banking bill. Instead of nationalizing the banks—as a few reformers wished—it offered aid to private bankers. A few days later the president forced through an Economy Act that cut $400 million from government payments to veterans and $100 million from the salaries of federal employees. This deflationary measure hurt purchasing power. FDR concluded his early program by securing legalization of beer of 3.2% alcoholic content by weight. By the end of 1933, ratification of the 21st Amendment to the U. S. Constitution had ended prohibition altogether.

Relief Legislation.

His relief program was more far-reaching. A series of measures took the nation off the gold standard, thereby offering some assistance to debtors and exporters. He also got Congress to appropriate $500 million in federal relief grants to states and local agencies. Harry Hopkins, who headed the newly created Federal Emergency Relief Administration, quickly spent the money. By early 1935 he had supervised the outlay of $1.5 billion more in direct grants, and in work relief under the Civil Works Administration (CWA) of 1933-1934.

In 1933, Congress also approved funding for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), and the Public Works Administration (PWA). The CCC eventually employed more than 2.5 million young men on valuable conservation work. The HOLC offered desperately needed assistance to mortgagors and homeowners. The PWA, while slow to act, ultimately pumped billions into construction of large-scale projects. Though left-wing critics demanded higher appropriations, most Americans were grateful for these measures. The relief programs of the New Deal gave hope to the have-nots—blacks and the unemployed—and did much to restore confidence in the government.

Reform Measures.

The early New Deal also sponsored reform measures. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) came primarily from congressional initiative. By insuring deposits, it helped to prevent ruinous runs on banks. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), created in 1934, made a cautious beginning toward regulation of the stock exchanges.

The most important reform was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), instituted in 1933. This public corporation built multipurpose dams to control floods and generate cheap hydroelectric power. It manufactured fertilizer, fostered soil conservation, and cooperated with local agencies in social experiments. The TVA reflected Roosevelt’s commitment to resource development and his longstanding mistrust of private utilities.

The NRA and the AAA.

FDR placed his hopes for economic recovery in two agencies created in the productive “100 Days” of the 1933 special session of Congress. These were the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). The NRA encouraged management and labor to establish codes of fair competition within each industry. These codes outlined acceptable pricing ana production policies and guaranteed labor the rights of collective bargaining, minimum wages, and maximum hours. The AAA focused on raising farm prices, a goal to be achieved through the setting of production quotas approved by farmers in referenda. Once the quotas limiting production were established, farmers who cooperated would receive subsidies.

After a promising start the NRA lost its effectiveness. Union spokesmen grumbled that the courts undercut the labor guarantees. Progressives complained that the NRA exempted monopolies from antitrust prosecution. Small businessmen protested that the codes favored large corporations. Some employers were slow to sign the codes, and others evaded them. If the PWA and other spending agencies had moved more quickly to promote purchasing power, these liabilities might not have been serious. As it was, the PWA was slow to spend its funds, hard times persisted, and evasion spread. Well before the Supreme Court declared the agency unconstitutional in May 1935, the NRA had failed in its aims of sponsoring government-business cooperation and promoting recovery.

The AAA was a little more successful. Agricultural income increased by 50% in Roosevelt’s first term. Some of this increase, however, was attributable to terrible droughts. These, ruining thousands of farmers in the Great Plains, caused cuts in supply and contributed to higher prices for crops produced elsewhere. AAA acreage quotas also led some landlords to evict tenants from their lands. Moreover, as the AAA improved farm prices, it forced consumers, millions of whom lacked adequate food and decent clothing, to pay more for the necessities of life. Roosevelt, it seemed, was fighting scarcity with more scarcity.

Assessing the Early New Deal.

These early measures displayed Roosevelt’s strengths and weaknesses as an economic thinker. On the one hand, he showed that he was flexible, that he would act, and that he would use all his executive powers to seciire congressional cooperation. Frequent press conferences, speeches, and fireside chats— and the extraordinary charisma that he displayed on all occasions—instilled a measure of confidence in the people and halted the terrifying slide of 1932 and 1933. These were important achievements that brought him and his party the gratitude of millions of Americans.

At the same time his policies were so flexible as to seem inconsistent, opportunist, and ill-considered. They showed him also to be a very cautious political leader. Neither then nor later in his administrations did he support civil rights legislation, which would have alienated the important Southern Democrats in Congress. Political considerations prompted his generous handling of potent interest groups, such as large corporations and commercial farmers. Far from imposing federal blueprints on the nation, he favored decentralization and voluntarism—these gave well-organized groups wide latitude and power. FDR also refrained from large-scale deficit spending or from tax policies that would have ‘ redistributed income. Purchasing power, essential to rapid recovery, therefore failed to increase substantially. Roosevelt, a practical political leader and a moderate in economics, helped preserve capitalism without significantly correcting its abuses or ending the Depression.

The New Deal from 1935.

In 1935, Roosevelt turned slightly to the left. He sponsored bills aimed at abolishing public-utility holding companies, at raising taxes on the wealthy, and at shifting control of monetary policy from Wall Street bankers to Washington. When Congress balked, Roosevelt compromised. The bills revealed Roosevelt’s loss of faith in government-business cooperation. They helped undercut demagogues like Sen. Huey Long (D-La.), who was agitating for tougher laws against the rich. But they did not signify a commitment to radical, antibusiness policies.

While these struggles were taking place, Roosevelt worked successfully for three significant acts passed in 1935. One, a relief appropriation, led to creation of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA disbursed some $11 billion in work relief to as many as 3.2 million Americans a month between 1935 and 1942.

The second measure, the Wagner Act, set up the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which effectively guaranteed labor the right to bargain collectively on equal terms with management. In part because of the Wagner Act, in part because of overdue militance by spokesmen for industrial unionism, the labor movement swelled in the 1930’s and 1940’s.

The third reform was social security. The law provided for federal payment of old-age pensions and for federal-state cooperation in support of unemployment compensation and relief of the needy blind, of the disabled, and of dependent children. The act, though faulty in many ways, became the foundation of a partial welfare stat^ with which later administrations dared not tamper.

These accomplishments helped Roosevelt win a smashing victory in 1936 over his Republican opponent, Gov. Alfred M. Landon of Kansas. Roosevelt received 27,751,841 popular votes and carried 46 states with 523 electoral votes. Landon received 16,679,491 votes and carried only two states with eight electoral votes. Although the result of the election reflected overwhelming confidence in FDR’s leadership, he still felt obliged to observe, in his 1937 inaugural address, “I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished.”

Controversy disrupted the president’s second term. His troubles began in February 1937, when he called for a “court reform” plan that would have permitted him to add up to six judges to the probusiness U.S. Supreme Court. The court’s conservative majority had angered FDR by declaring some New Deal legislation, including the NRA and AAA, unconstitutional. Congress, reflecting widespread reverence for the court, refused to do his bidding.

At the same time, militant workers staged “sit-down” strikes in factories. Though Roosevelt opposed the sit-downs, conservatives were quick to blame him for the growing activism of organized labor. In the fall of 1937 a sharp recession, caused in large part by cuts in federal spending earlier in the year, staggered the country. Taken aback, Roosevelt waited until the spring of 1938 before calling for increased federal spending to recharge purchasing power. His procrastination revealed again his reluctance to resort to deficit spending.

These developments in 1937 and 1938 severely damaged his standing in Congress, which had grown restive under his strong leadership as early as 1935. In FDR’s second term, therefore, the lawmakers proved cooperative only long enough to approve measures calling for public housing, fair labor standards, and aid to tenant farmers. None of these acts, however, was generously funded or far-reaching. Meanwhile, Congress cut back presidential requests for relief spending and public works. After Republican gains in the 1938 elections, a predominantly rural conservative coalition in Congress proved still more hostile. Henceforth it rejected most of the urban and welfare measures of Roosevelt’s administrations.

Foreign Affairs.

Cordell Hull of Tennessee served as secretary of state from 1933 to 1944, but Roosevelt’s desire to engage in personal diplomacy left Hull in a reduced role. In 1933 the president’s “bombshell message” to the London Economic Conference, saying that the United States would not participate in international currency stabilization, ended any immediate hope of achieving that objective. In the same year he extended diplomatic recognition to the USSR, still a relative outcast in world diplomacy.

Roosevelt and Hull worked smoothly in behalf of reciprocal trade agreements and in making the United States the “good neighbor” of the Latin American countries.

Prelude to War.

By the mid-1930’s dictatorial regimes in Germany, Japan, and Italy were casting their shadows across the blank pages of the future. In 1936, in his speech accepting renomination as president, Roosevelt had said, “This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.” By 1938, Roosevelt was spending increasing amounts of time on international affairs. Until then he had acquiesced in congressional “neutrality” acts designed to keep the United States out of another world war. Roosevelt did not share the isolationist sentiments that lay behind such legislation. But he hoped very much to avoid war, and he dared not risk his domestic program by challenging Congress over foreign policy. For these reasons he was slow to warn the people about the dangers of German fascism.

Germany’s aggressiveness in 1939 forced Roosevelt to take a tougher stance. Early in the year he tried unsuccessfully to secure revision of a neutrality act calling for an embargo on armaments to all belligerents, whether attacked or attacker. When Hitler overran Poland in September and triggered the formal beginning of World War II, Roosevelt tried again for repeal of the embargo, and succeeded. In 1940 he negotiated an unneutral deal with Britain whereby the British leased their bases in the Western Hemisphere to the United States in return for 50 overaged American destroyers. Roosevelt also secured vastly increased defense expenditures, which brought about domestic economic recovery at last. But he still hoped to keep out of the war and to appease the anti-interventionists in Congress. Thus he remained cautious.

Campaigning for reelection in 1940 against Wendell Willkie, a relatively progressive Republican who agreed with some of his policies, Roosevelt said misleadingly that he would not send American boys to fight in foreign wars. Many persons, including some leaders of the Democratic party, were not in favor of giving the president an unprecedented third term, and his margin fell sharply from his previous reelection. Nevertheless, he still defeated Willkie handily by margins of 27,243,466 to 22,334,413 in the popular vote and 449 to 82 in the electoral vote.

Safely reelected, Roosevelt called for “lend-lease” aid to the anti-German allies. This aid, approved by Congress, greatly increased the flow of supplies to Britain. After Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, lend-lease went to the Russians as well.

To protect the supplies against German submarines, U. S. destroyers began escorting convoys of Allied ships part way across the Atlantic. In the process the destroyers helped pinpoint the location of submarines, which Allied warships duly attacked. Roosevelt did not tell the people about America’s unneutral actions on the high seas. When a German submarine fired a torpedo at the American destroyer Greer in September 1941, he feigned surprise and outrage and ordered U. S. warships to shoot on sight at hostile German ships. By December the United States and Germany were engaged in an undeclared war on the Atlantic.

Most historians agree that Hitler was a menace to Western civilization, that American intervention was necessary to stop him, and that domestic isolationism hampered the president’s freedom of response. But they regret that Roosevelt, in seeking his ends, chose to deceive the people and to abuse his powers.

Historians also debate Roosevelt’s policies toward Japan, whose leaders were bent on expansion in the 1930’s. Hoping to contain this expansion, the president gradually tightened an embargo of vital goods to Japan. He also demanded that Japan halt its aggressive activities in China and Indochina. Instead of backing down, the militarists who controlled Japan decided to fight, by attacking Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941, and by assaulting the East Indies. These moves left no doubt about Japan’s aggressive intentions. In asking for a declaration of war, the president called December 7 “a date which will live in infamy.” He brought a united America into World War II. By December 11, the United States was at war with Germany and Italy.

Some historians argue, however, that Roosevelt should not have been so unbudging regarding the integrity of China and Indochina, which lay outside America’s national interest—or power to protect. If Roosevelt had adopted a more flexible policy toward Japan, he might have postponed a conflict in Asia at a time when war with Hitler was about to erupt.

World War II at Home.

In running the war effort Roosevelt encountered almost endless difficulties on the domestic front. Congress dismantled New Deal agencies such as the WPA and blocked such liberal proposals as aid to education and health insurance. Blacks, angry at continuing racial injustice, threatened to march on Washington in 1941. Fearful of racial disorder, Roosevelt responded by signing an executive order setting up a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to prevent discrimination in defense-related employment. Though the order was his most important action on behalf of civil rights, the FEPC did not have much power, and racial tension mounted throughout the war.

Industrial controversies proved equally troublesome for the president. In order to encourage cooperation from corporate interests, Roosevelt brought business leaders into policy-making positions, offered corporations generous contracts and tax breaks, and downgraded progressive domestic reforms. Furious liberals protested against this growing power of big business. Other critics complained that Roosevelt refused to delegate authority over mobilization to a “czar” who would have power to establish priorities for production. The lack of centralized authority caused confusion, bureaucratic conflict; and delays in output.

Frustrated, some of Roosevelt’s own appointees concluded that he was a sloppy administrator. In one sense their complaint was just, for Roosevelt welcomed rivalries among his subordinates. One bitter public quarrel pitted Vice President Henry Wallace, who had replaced Garner on the Democratic ticket in 1940, against Secretary of Commerce Jesse Jones. FDR had assigned both Wallace, a liberal, and Jones, a conservative Texas banker, important responsibilities in procuring urgently needed war supplies. Wallace was eager to spend money aggressively in underdeveloped countries and to introduce social reforms in the process. As other members of the administration chose sides, Roosevelt had to relieve both officials of their special assignments.

Despite such incidents, the president thought that competition bred new ideas. And, in fact, Roosevelt’s untidy administrative methods did no serious harm. By 1943 he had created a number of boards and agencies to control prices, develop manpower policy, and supervise the allocation of scarce materials. Fired by zeal to win the war, workers and employers ordinarily cooperated with the government to create production miracles.

Military Policies.

Roosevelt’s military policies also provoked controversy. In 1941 critics blamed him for leaving Pearl Harbor unprepared. Extremists even claimed that he invited the Japanese attack in order to have a pretext for war. In 1942 liberals complained when he cooperated with Jean Darlan, the Vichy French admiral who until then had been collaborating with the Axis, in planning the Allied invasion of North Africa. In 1943, FDR’s opponents grumbled that his policy of unconditional surrender for the enemy discouraged the anti-Hitler resistance within Germany. Other critics complained that he relied too heavily on strategic bombing. His own generals were angry because he postponed the “second front” against Hitler until June 1944. Such delay, critics added later, infuriated the Soviet Union, which had to carry the brunt of the fighting against Hitler between 1941 and 1944, and sowed the seeds of the Cold War.

Some of these criticisms were partly justified. Poor communications between Washington and Hawaii helped the Japanese achieve surprise at Pearl Harbor. Dealing with Darlan was probably not necessary to ensure success in North Africa. Strategic bombing killed millions of civilians and was not nearly so effective as its advocates claimed. The delay in the second front greatly intensified Soviet suspicions of the West.

But it is easy to second-guess and to exaggerate Roosevelt’s failings as a military leader. The president neither invited nor welcomed the Pearl Harbor attack, which was a brilliantly planned maneuver by Japan. He worked with Darlan in the hope of preventing unnecessary loss of Allied lives. Unconditional surrender, given American anger at the enemy, was a politically logical policy. It also proved reassuring to the Soviet Union, which had feared a separate German-American peace. Establishing the second front required control of the air and large supplies of landing craft, and these were not assured until 1944. In many of these decisions Roosevelt acted in characteristically pragmatic fashion—to win the war as effectively as possible and to keep the wartime alliance together. In these aims he was successful.

Wartime Diplomacy.

Similar practical considerations dictated some of Roosevelt’s diplomatic policies during the war. Cautious of provoking the British, he refrained from acting effectively against colonialism. Embarrassed by the delay in the second front—and anxious to secure Russian assistance against Japan—he acquiesced at the Teheran (1943) and Yalta (1945) summit conferences in some of Russia’s aims in Asia and eastern Europe. In his dealings with Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Britain and Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union, Roosevelt also showed an exaggerated faith in the power of his personal charm. The joviality and exuberance that had soothed ruffled congressmen and bureaucrats during the early New Deal days were not so well suited for international politics.

In the larger sense Roosevelt’s diplomacy, like his military policies, was statesmanlike. Despite occasional strains, the awkward wartime coalition among Russia, Britain, and the United States held together. Roosevelt was also wise in recognizing the futility of trying to stop Russian penetration of eastern Europe, which Soviet armies had overrun by early 1944. Accordingly, he sought to avoid unnecessary bickering with Stalin. Had FDR lived into the postwar era, he could not have prevented divisions from developing between Russia and the United States. But he might have worked harder than did his successors in compromising them.

Reelection in 1944.

In 1944, with the war still in progress, the tired but willing commander in chief stood for reelection for a fourth term. His doctors knew that he was suffering from hypertension, hypertensive heart disease, and cardiac failure. Some of the president’s advisers suspected as much, and they feared that he might not live through another term. So they persuaded him to drop Vice President Wallace, whom they regarded as too liberal and as emotionally un-suited to be president, and to accept Sen. Harry Truman ( Mo. ) for the vice presidency. In the 1944 general election, Roosevelt defeated his fourth Republican opponent, Gov. Thomas Dewey (N. Y.), by 25,612,474 popular votes to 22,017,570, and by 432-99 in electoral votes.

Death.

By 1945, Roosevelt was 63 years old. The events early in that year added to the strains on his heart, and on April 12, 1945, he died suddenly at Warm Springs, Ga. Three days later he was buried at Hyde Park. Despite his limitations, he had been a strong, decent, and highly popular president for more than 12 years.

mavi