What are the phases of French Revolution? Information on the religious reforms, fall of monarchy and the summary of French Revolution.

PHASES OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION, 1789-1814

Once under way, the Revolution became a search for a political order that would reconcile the conflicting needs of the individual, the nation, and the state. As such, it passed through four phases. The first (1789-1792) was identified with constitutional monarchy, and the second (1792-1795) with militant democratic republicanism. The third (1795-1799) witnessed an effort to retreat to moderate republicanism. The fourth (1799-1814) produced a dictatorship, disguised first as a democracy and later as an imperial state that in theory was sanctioned by the people. Unfortunately for the liberal and democratic tradition, it was the last regime, the Consulate and the Empire, that seems to have given the most satisfaction to the average Frenchman.

Constitutional Monarchy.

In the first phase of the Revolution, the French state was profoundly and comprehensively reorganized. The rationale for the period is found in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, which affirms the liberty of the individual, the separation of powers, the sovereignty of the people, and civil equality. The political institutions of the regime were prescribed in constitutional decrees passed during the next several months. The decrees were combined into a constitution adopted in the summer of 1791.

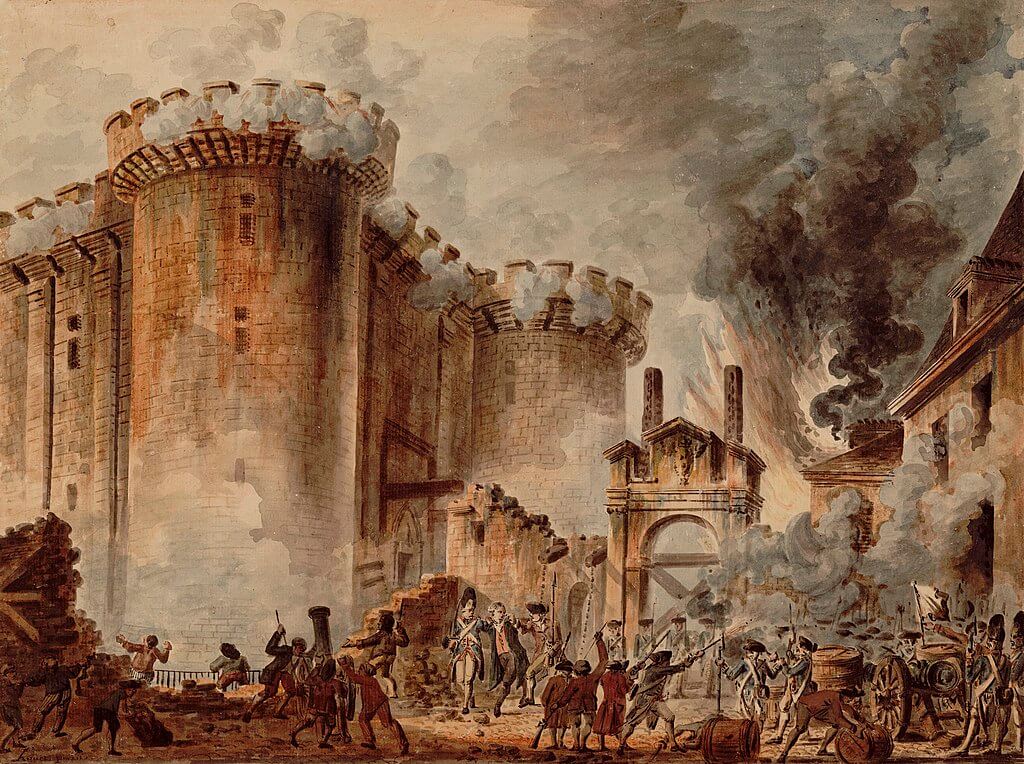

Source : wikipedi.org

Broadly speaking, the Constitution of 1791 established an elected legislature meeting annually, an executive branch headed by the king but almost powerless in the face of the legislature, an elected judiciary, and elected organs of local government that replaced the old centralized bureaucracy responsible to the king alone. Although only two thirds of the adult males qualified to vote for electors and although only 46% were eligible to be chosen electors and, as such, to vote for deputies to the Legislative Assembly, the constitution—judged by the standards of the day—may be called democratic as well as liberal.

The early Revolution was remarkable not only for what it established but for what it swept away. The decrees of Aug. 4, 1789, passed in response to the formidable peasant disturbances called the Great Fear, suppressed many aristocratic features of the ancien régime. These included such features of “feudalism” as seignorial dues and obligations and seignorial courts, as well as the compulsory church tithe, purchase or inheritance of office, status qualifications for office, and legal and fiscal inequality. By abolishing parlements, provincial estates, municipal corporations, and guilds, the revolutionaries broke up the organized vested interests and the regional and local oligarchies of old France and smashed the system of privilege and power associated with birth. In other words, they destroyed aristocracy as a political system. In June 1790 they abolished the institution of nobility. It was a revolution of equality. But the meaning of equality can best be perceived in the light of what was demolished.

Religious Reforms.

The first French Revolution was heavily concerned with religion. Although the revolutionaries continued to recognize the Roman Catholic Church as an established church, they reformed it and granted toleration for other faiths. In order to liberate France from the enormous debt that had brought about the political crisis of 1787—1788, they expropriated the property of the church and put it up for sale, providing at the same time that the state would pay clerical salaries and other costs. Since the church had received its wealth from the people and would henceforth be state-supported, the sponsors of these reforms argued that it needed no property endowments and that its wealth could be appropriated for national needs.

Source : wikipedi.org

Other measures affecting Catholicism followed the expropriation. In February 1790, monasticism was suppressed. In July the Assembly enacted the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which provided that persons chosen to be electors of the districts and departments should elect the priests and bishops; it also virtually broke all connections between the French Catholic Church and Rome. These changes aroused strong and even violent feelings against the Revolution, and these animosities were intensified in the spring of 1791, when Pope Pius VI publicly condemned the Revolution and forbade the French clergy to swear loyalty to the constitution. The effect of all this was to alienate large sectors of the common people and to create much more opposition than the revolutionaries had foreseen. In effect, the religious reforms of 1790 democratized the counterrevolution, since the indignation of the peasants and working people was added to that of the formerly privileged orders.

Fall of the Monarchy.

The reforms of 1789-1791 generated tensions that led to the insurrection of Aug. 10, 1792, and destroyed the first revolutionary settlement. Among the factors that seemed to endanger the Revolution and its partisans were the resentment of nobles and officials over their lost status; the formation of a small army in the Rhineland by army officers who had emigrated; Roman Catholic indignation at the religious reforms; outbreaks, even if unsuccessful, of counterrevolutionary resistance; and a growing external threat to the Revolution, led chiefly by the Habsburg and Prussian monarchies. Among the revolutionists, there arose increasingly militant leaders and factions, who feared that moderation would imperil all that had been won and who associated moderation with counterrevolution. A republican movement emerged after the King’s abortive attempt in June 1791 to escape and to lead the northeastern garrisons back to the capital to seize power and to “royalize” the constitution.

On April 20, 1792, the Legislative Assembly, which was the first to be elected under the new constitution, unwisely declared war on the Habsburg monarchy. The first two weeks of the war showed that the army was helpless and that France was open to invasion. The King’s behavior convinced extremists of the Commune of Paris that he was collaborating with the enemy, and on August 10, several thousand insurrectionists, organized by Commune leaders, attacked the royal palace and forced the Legislative Assembly to suspend the monarchy and to call for a new constitutional convention that would establish a republic. This insurrection of August 10, which the historian Albert Mathiez called the Second French Revolution, opened a new phase, which was to be republican and democratic in name but totalitarian in fact.

Source : wikipedi.org

The National Convention.

The Second phase of the Revolution opened with the election of the National Convention, which was to govern France until October 1795. About 85% of the eligible voters—indifferent, hostile, frightened, or intimidated—abstained from voting. The Convention, therefore, had the sanction of only a small minority. Yet it believed itself vested with the authority of the people and undertook to govern in their name and collective interest, which it saw as the defense of the Revolution and everything for which it stood. Unfortunately, internal and external opposition made it impossible for the Convention to defend the Revolution in ways consistent with liberalism and democracy, and, beginning in 1793, it was forced to govern révolutionnairement (“in a revolutionary manner”), using devices and practices that the 20th century would consider totalitarian.

Threatened by invasion, insurrection, and economic crisis, the Convention had to set aside the constitution of 1793 before it could be implemented. The constitution was a model of democracy that would have legitimized opposition and would have made it possible for enemies of the militant republic to take power. Step by step, the Convention established a monopoly of control and acted the way revolutionary elites are obliged to act when governing an indifferent or hostile majority. Local governing bodies were purged by the Convention’s representatives-on-mission and directed by its committees, particularly the Committee of Public Safety and the Committee of General Security. Deputies-on-mission were assigned to the armed forces, where they purged or punished officers who were untrustworthy or unfit. They also supervised campaigns.

The Terror.

In dealing with the badly disordered economy, the Convention fixed prices and wages and reallocated labor and commodities to help meet the threat posed by the invasion of France by members of the First Coalition. Jacobin clubs, established in all towns, seconded the Convention’s acts and policies, supervised public and cultural life, watched the conduct of officials, and pursued a program of propaganda and indoctrination. The press conformed. Suspects were arrested and held without trial. Revolutionary courts, ignoring the procedural safeguards of civil and criminal justice, tried those accused of sedition and other political crimes. Although this program of extraordinary repression, called the Reign of Terror, lacked the scope and ferocity of modern totalitarian purges (only 1 in 700 of the population perished because of it), its processes were much the same. The Convention, while not exterminating opposition, neutralized it and kept it from acting with effect. It repelled invasions and organized a victorious offensive against the First Coalition in the spring and summer of 1794. By suspending liberty and democracy, the Convention in effect defeated the counterrevolution and won the war against the European supporters of monarchism, and in so doing the Convention justified to itself its leadership and policies.

Thermidorean Reaction.

The second phase of the French Revolution ended with the Thermidorean Reaction, which took place during the second half of 1794 and the first half of 1795. On July 27 (9 Thermidor), 1794, the Convention forestalled a purge of its ranks by having Maximilien Robespierre and four other deputies arrested. The execution of Robespierre shocked Jacobins all over France. For the minority that supported the Convention, he embodied the patriotism, wisdom, vigilance, and probity of the republic. In order to justify proscribing him, however, his colleagues accused him of aspiring to become a dictator and of perverting the Terror. In destroying the image of the virtuous Robespierre, they damaged the confidence of Jacobins in the revolutionary government, cast doubt on the rationale of the Terror, and wrecked the morale of the militant minority, whose support they needed. Consequently, they tried to win the acceptance of moderate adherents of the Revolution and, as a means of doing this, dismantled the Terror. The dismantling of the Terror in the fall and winter of 1794-1795 is called the Thermidorean Reaction. It was an unplanned consequence of the proscription of Robespierre.

Source : wikipedi.org

As an experiment in reconciliation, the Thermidorean Reaction was a failure. None of the suspects who were released, no one who had lost property or profits, none whose friends or kinsmen had perished in the Terror or in unsuccessful rebellions were ready to forgive what the Convention had done in the name of defending the revolution and the nation. Steadfast Catholics, nobles, and partisans of the ancien régime remained unreconciled, and the Convention unintentionally strengthened the opposition by tolerating a revival of religious worship, which became in many pulpits a means of rallying the discontented against the republic. Trials of onetime terrorists like Jean Baptiste Carrier, who as repre-sentative-on-mission at Nantes had presided over the liquidation of some three thousand persons, further discredited the Terror and its sponsors.

In a final bid for solidarity, the Convention, in May 1795, adopted the Constitution of the Year III, which was meaijt to end the Revolution by reestablishing representative government and by providing guarantees under which individuals, including the deputies, could find shelter from political retaliation and persecution. The constitution’s implementation in October 1795 marked the beginning of die third phase of the Revolution, that of the Directory.

The Directory.

As a government, the Directory lasted barely more than four years. Although the constitution failed in practice, the period is remarkable for the expansion of French control into the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Italy; the establishment of satellite republics on the frontiers; and the emergence of the French Army as the decisive element in French politics.

The designers of the constitution of 1795 wanted to block, through separation of powers, the reappearance of the type of state created by the Convention. Legislation was entrusted to a bicameral parliament, and executive functions were vested in a board of five directors, none of whom could sit in the legislative chambers or could succeed himself immediately in office. Safeguards were established against the power of individuals or of committees. In order to promote stability, youth was excluded from office: members of the Council of Five hundred had to be at least 30; directors and the 250 members of the Council of Ancients had to be at least 40. In order to assure their control of the new government during its first two years, the members of the Convention required that at least 500 of the first 750 legislators be chosen from the Convention.

It is unlikely that any genuinely representative form of government could have succeeded in France after 1795, because the animosities created by the Revolution had made men unwilling to accept constitutional limits on political action. Both the royalists, reinforced by returning émigrés, and the survivors of extreme revolutionary factions conspired against the new regime.

Threatened from right and left, the sponsors of the Directory suspended liberties, arrested priests and other suspects, deported many of its opponents, muzzled the press, and excluded duly elected deputies from the chambers. The economy remained inflationary and unstable. The presence of large numbers of deserters and fugitives from conscription combined with the collapse of old values to generate an alarming crime rate. The socialist Conspiracy of Equals in 1796, though small and impotent, frightened the governing circles and the well- to-do.

Source : wikipedi.org

War and the Army.

The war against the Second Coalition, which opened in 1798, brought military and naval reverses. On Aug. 1, 1798, the Mediterranean fleet was almost totally destroyed at Abukir Bay, isolating Gen. Bonaparte’s army in Egypt. Early in 1799, Austrian troops drove the French out of Germany, and Austrian and Russian forces swept them out of Italy and invaded Switzerland, while an Anglo-Russian army invaded the Dutch Netherlands. In the summer of 1799, Abbé Sieyès, a director who was also a veteran of both the Estates General and the Convention, began to plan a military coup d’etat to establish a new government that would combine stability with respect for individual rights. As his principal collaborator he enlisted, with some misgivings, the popular hero Bonaparte, who had returned from Egypt in October. Originally a partner in the plot, Bonaparte swiftly took charge, representing, as he did, the power of the army.

The army of revolutionary France differed vastly from that of the ancien régime. Men were commissioned without regard to birth and were promoted on merit. Beginning with the residue of the old army, reinforced with new recruits, seasoned in combat, united by the experience of hard campaigns and notable victories, and infused with enthusiasm for its young hero-generals, the army developed a self-consciousness and sense of community. It became a distinct social formation, with its own interests, values, and aspirations. During the Directory the revolutionary élan of earlier years gave way to a general distrust of the civilian government in Paris. In 1795 and 1797 the Paris garrison took part in suppressing royalist insurrections; and in 1797, Bonaparte conducted the peace negotiations with Austria with a cynical indifference to the Directory’s instructions. The coup d’etat of 18-19 Brumaire ( Nov. 9-10, 1799 ) marked the ascendancy of the army, personified in Bonaparte, over the civilian government.

Consulate and Empire.

The coup of Brumaire opened the fourth and final phase of the French Revolution. Although the Constitution of the Year VIII was drawn up on outlines provided by Sieyès, Bonaparte insisted on modifications that in effect put the whole governmental apparatus under his control. All the essential principles of the Revolution—universal manhood suffrage, separation of powers, civil equality, sovereignty of the people, and individual rights—were affirmed in this document. The Constitution was deceptive. In practice it established a dictatorship directed by Bonaparte, who began as First Consul (1799), then had himself made Consul for Life (1802), and finally elevated himself to Emperor of the French (1804), making appropriate constitutional changes as he did so. Bona-partist government is rightly described, diere-fore, as dictatorship disguised as democracy. It had much in common with 20di century fascism.

On balance, however, the Bonapartist state, as directed by its founder, seems to have satisfied the French better than any government the Revolution provided. As chief of state Bonaparte pacified the country, stabilized the monetary and credit system, maintained order, reestablished Catholicism, restored relations with Rome, codified the laws, improved public works, and set up a bureaucracy that, though occasionally corrupt, was incomparably efficient. Although the press was regimented and the opposition was watched and controlled by police-state methods, Bonapartist despotism was benign and never required a reign of terror. Levies on occupied territories and satellite states solved financial problems and made excessive taxation in France unnecessary. Until 1810 the economy was prosperous.

Except for military conscription and the high war casualties, the French complained little and seemed happy to accept prosperity and the glory of dominating Europe in place of the goals of the early Revolution. Until 1812, conspiracies against the new order were small, infrequent, and easily controlled. It was outside France, particularly in Spain and Germany, that Bonapartism encountered serious popular resistance. The French repudiated the Napoleonic system only in 1814, when the armies of the last coalition had all but conquered the country.

mavi