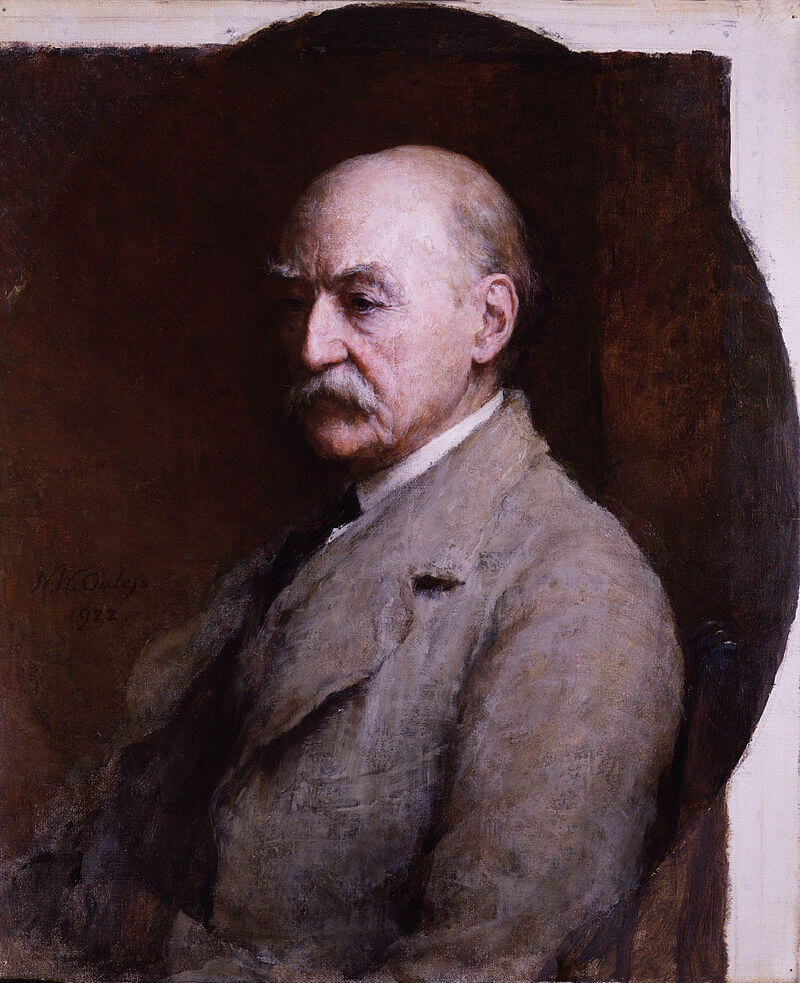

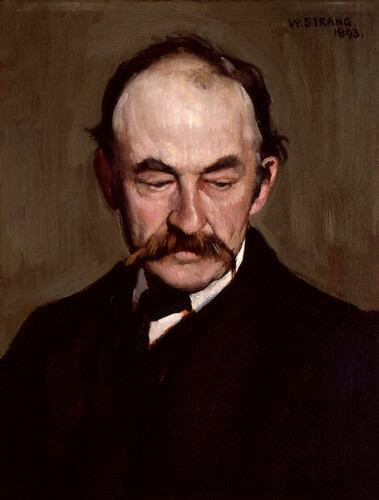

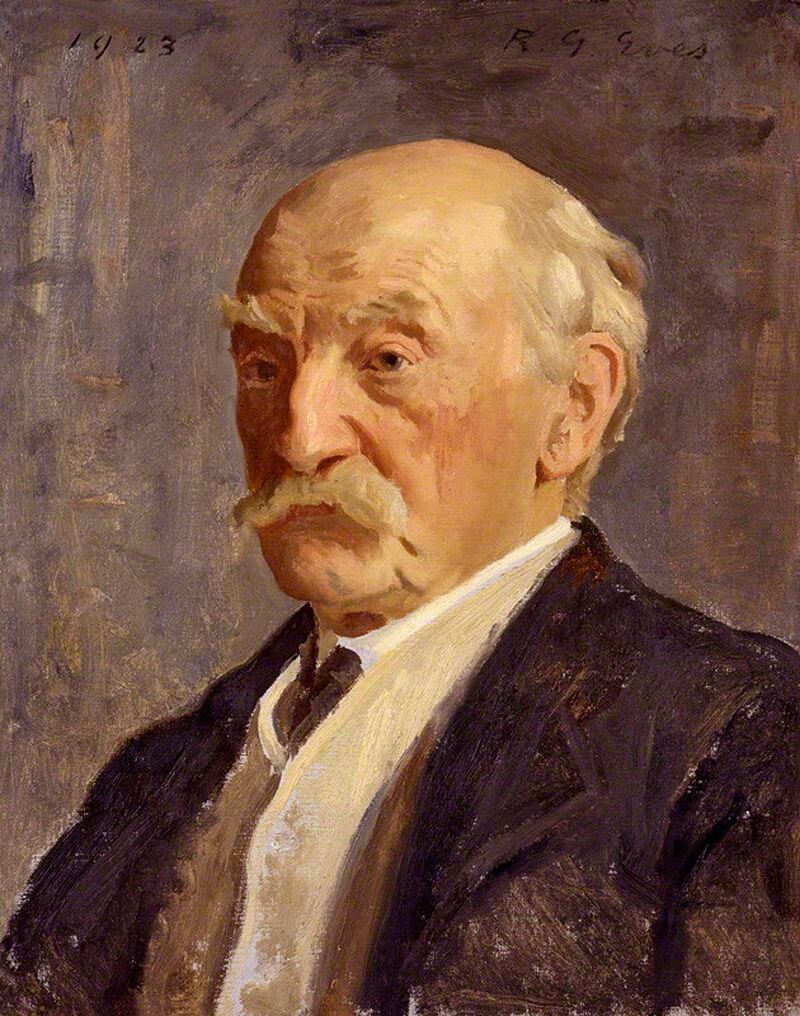

Who was Thomas Hardy? Information about the novelist and poet Thomas Hardy biography, life story and works.

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), English novelist, who portrayed rural life in the fictional locale of “Wessex” in southwestern England. His novels treat country people with respect and humor, and they comment on the human lot with a kind of religious feeling modified by agnostic reasoning. Hardy abandoned fîction in 1896 to publish eight volumes of poetry in addition to The Dynasts, an epic-drama of the Napoleonic Wars, in three parts, 19 acts, and 130 scenes.

Source: wikipedia.org

Formative Years.

Hardy was born in Higher Bockhampton, 2,5 miles from Dorchester, on June 2, 1840. He was the son of a mason also named Thomas Hardy. When “Tommy” was four, his father taught him to play the violin, and througlıout Hardy’s boyhood father and son fiddled for country dances.

Tommy attended school in Dorchester, and began studying Latin at the age of 12. He listened eagerly to his grandmother’s tales, especially those of the Napoleonic era, and pored over old issues of an illustrated periodical, A History of the Wars. ile attended church regularly, more or less memorized the services, began teaching Sunday school at 15, and dreamed of preparing himself to be a minister.

In 1856, Hardy put aside his dream and became an apprentiee to architect John Hicks of Dorchester. Though no longer in school, Hardy rose at dawn to study Latin, and later Greek, on his own before trudging off to work. Hicks’ office was next to a school kept by the linguist William Barnes, and the boy took his scholarly problems to the schoolmaster. In 1857, Hardy came under the tutelage of Horace Moule, a scholar in classics at Cambridge. At this time Hardy purchased a Greek New Testament, which he read regularly throughout his life. In 1860, Moule introduced Hardy to Essays and Reviews, a collection of essays on religious subjects, critical of doctrine, and other writings that challenged orthodox religious concepts.

Hardy went to London in 1862 as an assistant to the architect Arthur Blomfield. In 1863 he won a medal for an essay entitled The Application of Coloured Bricks and Terra Cotta to Modern Architecture, and in 1865 he contributed the fictional How I Built Myself a House to Chambers’s Journal. This was his first publication.

Source: wikipedia.org

Hardy became ill in 1867 and returned home to recuperate. When his health improved, he resumed work for Hicks, became engaged to his cousin Tryphena Sparks, and wrote a novel, The Poor Man and the Lady. George Meredith, the reader for Chapman and Hail, told Hardy the views that it expressed were too radical for publication and advised him to write a novel with less reforming zeal and more plot. Leaving London, Hardy shelved the novel and went to work for an architect in Weymouth. In 1870 he wrote Desperate Remedies, a novel of love and erime with the kind of complex plot Meredith had advised. It was published anonymously in 1871 at the author’s expense.

In March 1870 his employer sent Hardy to St. Juliot’s Church in Cornwall to examine it with a view to repairs. There the young novelist met Emma Gifford, sister-in-law of the reetor, and despite his engagement to Tryphena, fell in love. After publishing his second novel, Under the Greenwood Tree (1872), Hardy wavered between arehiteeture and literatüre, but Emma assured him that literatüre was his “true vocation” and helped him by making a fair copy of A Pair of Blue Eyes, which was published in 1873.

Years of Achievement.

Giving up arehiteeture, Hardy concentrated on Far from the Madding Crowd. Published in 1874, this novel was his first success, and it enabled Hardy to marry Emma in September. After a honeymoon in France, the Hardys returned to London but then for several years wandered about—living in Swanage and Yeovil, visiting the Continent in 1876, and taking a house in Sturminster Newton, where Hardy wrote The Return of the Native (1878).

After The Trumpet-Major was published in 1880, Hardy, back in London, began A Laodicean. He was taken ili, and since the first chapters of the novel had already appeared serially, he dictated most of the rest of it from his bed. He was able to get up in April 1881, and in June the Hardys

Source: wikipedia.org

moved to Wimborne, where the author began Two on a Tower (1882). Finally they took lodgings in Dorchester, where Hardy had purehased land for building Max Gate, his home for the rest of his life. There he completed The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886) and The Woodlanders (1887).

In the spring of 1887, Hardy took his wife on an extended trip to Italy, retuming to publish a volume of short stories, Wessex Tales (1888). Although he was primarily a novelist and poet, in later years he published several more collections of stories, ineluding A Group of Noble Dames (1891) and Life s Little Ironies (1894).

After publishing the highly successful Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891) and the serial The Well-Beloved (1892), Hardy visited Great Fawley in Berkshire, the village where his paternal grandmother had grown up. There he began to plan Jude the Obscure, set partly in this village, which he called “Marygreen.” Hardy returned to London in the summer of 1893 to work on the novel. When Jude appeared as a book in 1895, reviewers attacked it savagely because of its frankness in dealing with sexual problems, with the result that Hardy turned to poetry—which to some extent he had been writing through the years. He published Wessex Poems in 1898.

Reviving longpondered plans for an epic-drama on the Napoleonic Wars, Hardy visited Brussels and Waterloo in 1896. He continued research for his epic but also published Poems of the Past and the Present (1901). In 1904, Part 1 of The Dynasts appeared; in 1906, Part 2; and in 1908, Part 3. Hardy published more poems as Time’s Laughingstocks (1909).

Later Years.

Emma died on Nov. 27, 1912. Though the couple had not been congenial since the 1890’s, her death affected him deeply. His memory revived their romance in “Lyonnesse” (Cornwall), and in March 1913 he visited there for the first time since his marriage, and returned to write his remarkable Poems of 1912—13, picturing his courtship. The poems were published in Satires of Circumstance (1914).

In February 1914, at nearly 74 years of age, Hardy married the 35-year-old Florence Dugdale, who had helped him with his research for The Dynasts. They retired to Max Gate and spent a quiet life, except for occasional trips to London, and the distresses of World War I. He devoted himself chiefly to memories and his poems, which were published as Moments of Vision (1917), Late Lyrics and Earlier (1922), and Human Shows (1925). He assembled Winter Words for publication on his birthday in 1928, but he died on January 11 of that year, and his widow brought out the poems in October. In the 1920’s, Hardy had written his autobiography in the third person. It appeared, with Florence Emily Hardy listed as author, in two parts: The Early Life of Thomas Hardy (1928) and The Later Years (1930). It was republished as The Life of Thomas Hardy (1965).

Hardy’s heart was buried near the remains of his first wife in Stinsford churchyard, but his ashes lie in Poet’s Corner, Westminster Abbey.

Novels.

Hardy was a realist in his portrayal of details, a romantic in feeling, a naturalist in philosophic outiook, and a meliorist in purpose. The places he deseribed in his “Wessex” are aetual, though given fictional names. “Wessex” comprises roughly the real counties of Dorset, Devon, and Somerset. Hardy’s “Casterbridge” is the Dorchester he knew, and “Egdon Heath” the wasteland behind his birthplace. As a romantic, he enriched his novels of common experiences with echoes of Shakespeare, Shelley, and the Scriptures. The lovers in his works nearly always idealize blindly, and for this reason often end in disaster. His symbolism anticipated that of post-Freudian writers—as seen in the sexual connotations of Troy’s swordplay in Far from the Madding Crowa—and his plots suggest Victorian melodrama, though as a craftsman he worked out details to make them seem inevitable.

Compassionate by temperament, Hardy found justification in evolutionary theory for extending compassion to all living creatures. He gave his heroes this feeling: the boy Jude feeds the birds he is supposed to frighten away, avoids stepping on earthworms, and defies Arabella in the matter of letting a pig bleed slowly to improve the pork. Hardy felt that even inanimate nature suffers as if alive. “Egdon Heath” is a “face”; it has voices; it listens and awaits the “final overthrow.” He felt the universe to be animated by the unconscious Will pictured later in The Dynasts. Man, in this concept, is one with nature, the nearly helpless puppet of Time and Chance. Yet man, through reason and loving kindness, can change the remediable ills of life, among them class systems, domestic tyrannies, cruelties, and war.

Hardy’s characters are the folk of “Wessex,” many or them humorously presented rustics, others able farmershepherds like Gabriel Oak in Far from the Madding Crood or men of iron will like Henchard of The Mayor of Casterbridge. Under the Greenıvood Tree is an idyll of rural characters, antiquated customs, and young love in “Mellstock” (Stinsford) in the decade before Hardy was born. Far from the Madding Crood studies a vain, capricious womanfarmer of “Weatherbury” (Puddletown) in her relations with three lovers: a loyal shepherd, a staid introvertdreamer, and a dashing soldier. She learns at last the worth of homely love versus passion, which is “evanescent as steam.”

Source: wikipedia.org

The Return of the Native pictures “Egdon Heath” as a microcosm whose natural laws are kind to those who adjust but crush those who rebel. The Mayor of Casterbridge traces the fail of an impulsive “man of character” in conflict with one more resilient and less selfcentered. The Woodlanders treats a girl’s unhappy choice of a husband and attacks the marriage laws that chain them together.

In Tess of the D’Urbervilles Hardy calls Tess, who had been violated as a girl, “a pure woman faithfully presented” and condemns the pruderies that bring her to a tragic end. Jude the Obscure, a story of mismatings, is a gloomy tragedy about a stonemason, not unlike the young Hardy, who desperately yeams for an education but whose involvement with the two women in his life leads him only to failure, misery, and ultimately death.

Poetry.

The English edition of Hardy’s Collected Poems (1930) contains 918 poems, narrative, dramatic, philosophic, elegiac, and lyric. Some teli balladlike stories; others depict episodes in the Napoleonic Wars. The philosophic poems treat fate, religion, and the Immanent Will.

Hardy’s poems are extraordinarily personal, many treating actual events. More than 100 present intimately his courtship of Emma GifFord and his life with her and with his second wife.

The poems, though often experimental in form, are not esoteric. Some have been widely antholo-gized, including When 1 Set Out for Lyonnesse, Hap, The Phantom Horsewoman, The Souls of the Slain, And There W as a Great Calm (the Armistice), The Convergence of the Tıvain (the Titanic disaster), and The Darkling Thrush.

Hardy’s crowning achievement is the play The Dynasts, in a variety of meters and in prose. It dramatizes the Napoleonic Wars from the time Napoleon crowned himself emperor until he was crushed at Waterloo. The dynasts—Napoleon, George III of England, and others—are the villains; the suffering peoples, “puppets in a playing hand,” the heroes. In the struggle among the dynasts, England is the chief protagonist. A second theme is the degeneration of Napoleon. The 130 scenes of The Dynasts sweep over Europe from England to Spain to Russia with magnifîcent climaxes in the battles of Trafalgar, Austerlitz, Borodino, and Waterloo. Above the human struggle, the Immanent Will— the “Ding an sich” of the philosophers that operates in man through impulses in the unconscious —manipulates the action. Some of the characters, spirits representing powers of the mind, debate the meaning of human actions: Years represents experience and reason; Pities, compassionate feeling; Sinister, the perversity of human nature; and Ironic, aloof intellect. In the conclusion, the Spirits sing hopefully that in eons to come consciousness may wake in the Will, “till It fashion all things fair!“

mavi