Who was Denis Diderot? What did Denis Diderot do? Information on Denis Diderot biography, lidfe story, works and philosophy.

Denis Diderot; (1713-1784), French encyclopedist, philosopher, and man of letters, who was one of the most dynamic leaders of the Enlightenment. During his lifetime he was best known as chief editor of the Encyclopedie (1751-1772). This great publishing enterprise, the largest attempted up to that time, was more than simply a comprehensive work of reference. It was also in tended, in Diderot’s own words, “to change the general way of thinking” and to bring about “a revolution in men’s minds.”

The 20th century, while continuing to recognize Diderot’s importance in the Enlightenment, especially esteems him as the author of a number of posthumously published works of extraordinary originality and daring. They have a vitality, an experimental quality, and a sense of life’s ambivalences and ambiguities that particularly engage the modern taste.

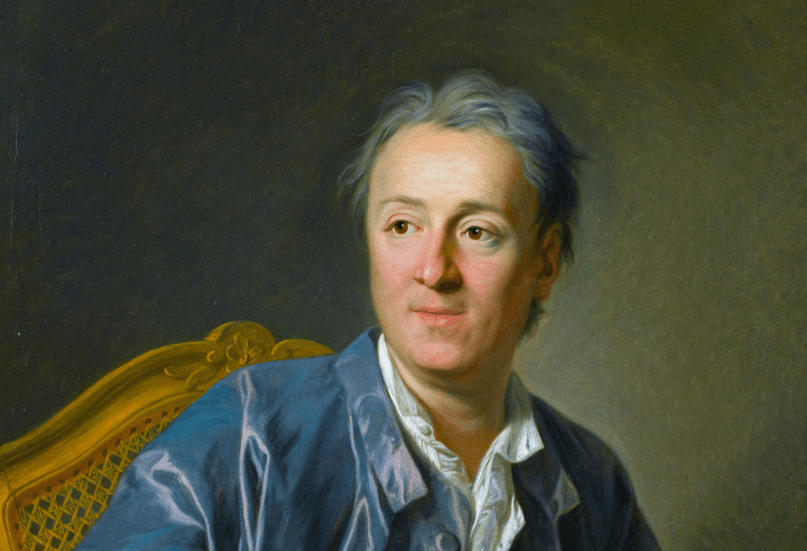

Denis Diderot (Source : wikipedia.org)

Early Life and Works.

Diderot was born at Langres, on Oct. 5, 1713. He studied at the Jesuit college there, probably attended the Jansenist College d’Harcourt in Paris, and received a master of arts degree from tiıe University of Paris. After 10 bohemian years, he married Anne Toinette Champion in 1743.

The world of letters first knew Diderot as a translator of English works: Temple Stanyan’s Grecian History (1743), Lord Shaftesbury’s Inquiry Concerning Virtue and Merit (1745), and Robert James’ Medicinal Dictionary (6 vols., 1746-1748) . in. 1746, Diderot published anonymously his own Pensees philosophiques, an influential book of deistic aphorisms, which was condemned to be burned by the public executioner. In 1748 he brought out anonymously a slightly obscene “philosophical” novel, Les bijoux indiscrets and, under his own name, a slender volume on physics and mathematics, Memoires sur differents sujets de mathematiques. He was imprisoned for three months in the Château de Vincennes in 1749 for having written the Lettre sur les aveugles, a book on the behavior of the blind, which also opened up questions of philosophical materialism and of the existence of God.

“Encyclopedie. “

In 1747, Diderot, aided by Jean d’Alembert, became editor of the Encyclopedie. Originally it was intended to be a translation of Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia (1728), but Diderot greatly expanded it. Its prospectus appeared in 1750, and the work itself was published from 1751 to 1772 in 17 volumes ol text and 11 volumes of engravings.

Diderot was a materialist. Questioning tradition and authority, he believed in the power of human reason, guided by sense experience, to increase human knowledge and well-being. He gathered like-minded writers and scientists to contribute to the Encyclopedie and himself wrote hundreds of articles for it. The most notable are those dealing with the history of philosophy and the crafts and industries of France.

The Encyclopedie, reflecting its editor’s point of view, frequently embodied proposals for social change and implicitly challenged much in the contemporary political and religious establishment. It was subject to censorship by the government and was a target of conservatives and reactionaries. Thus, the long struggle to bring the Encyclopedie to completion was part of the agitation for greater tolerance and greater freedom of expression that was an important element in the Enlightenment. In 1752 the govemment suspended the work for almost a year, and in 1759 it revoked Diderot’s license to publish. Subsequently, the work was allowed to proceed surreptitiously, but even so Diderot was not spared heartsickening disappointment: his publisher, Le Breton, secretlv altered many of the articles after Diderot had finished with them. Though Diderot discovered the deceit in 1764, he decided not to expose it; but he wrote to Le Breton, “I shall bear the wound until I die.“

Other Works.

Although Diderot complained that the Encyclopedie had used up—in writing, editing, proofreading, supervising of engravings, and other editorial tasks—fully 25 years of his life, he found time to write many other works that amply demonstrate the great range and versatility of his mind. Lettre sur les sourds et muets (1751), a book primarily on the behavior and psychology of deafmutes, also discussed poetics, aesthetics, and linguistics. Pensees sur l’interpretation de la nature (1753) was an influential short treatise on scientifie method. His two plays, Le fils naturel (1757) and Le pere de f amille (1758), greatly influenced the theater in their naturalistic portrayal of everyday middle-class life. Diderot aecompanied these plays with important supplementary essays on the theory of playwriting and production— Entretiens sur Le fils naturel (1757) and De la poesie dramatiçue (1758).

Many works that Diderot judged likely to be suppressed by the censors were published post-humously. In the novel La religieuse (1760; published 1796) he portrayed the distressing experiences of a young nun who wishes to renounce her vows. In Le neveu de Rameau (1761; published in German, 1805) he showed his mastery of the dialogue form, brilliantly satirizing his enemies while discussing music, creativity, genius, and ethics. For his Salons, a series of critiques of the Boyal Academy of Art’s biennial art exhibition, Diderot is often regarded as a founder of modern art criticism.

Le reve de d’Alembert (1769; published 1830) is a dialogue that treats the origin of organized matter and of life without presupposing a creator. It contains prophetic insights into chemistry and biology, which propel the reader into the 20th century world of genes and amino acids. The theory of acting is dealt with in Le paradoxe sur le comedien (1773; published 1830). The Supplâment au Voyage de Bougainville (1772; published 1796), while ostensibly discussing the mores of the Tahitians, aetually criticizes the laws and mores of contemporary Europe. The novel Jacques le fataliste et son maître (1771-1773; published 1796), long regarded as a bizarre and undisciplined effusion, has come to be considered a masterpiece that explores various levels of meaning ^and various kinds of novelistic techniques. Elements de physiologie (1774-1784; published 1875) shows Diderot’s remarkable familiarity with the medical and scientific researches of his day and especially reveals his insights into neurophysiology.

A defense of the Roman philosopher Seneca, published in 1779 and enlarged in 1782, was a kind of apology for his own life. It was followed by an autobiographical play, Est-il bon? Est-il mechant? (1781; published 1834), whose hero, with the best of intentions, minds everyone’s business but his own. Diderot also wrote several important philosophical tales, various lengthy memoranda, and some clever light verse.

Character and Later Life.

Among his many friends Diderot numbered the philosophers Holbach, Rousseau, Hume, Helvetius, and the Abbe Raynal; the literary figures Laurence Steme, Marmontel, and Sedaine; the criminologist Beccaria; the economist Galiani; the political leader John Wilkes; the actor David Garrick; and the sculptor E. M. Falconet, with whom he exchanged heated letters about immortality and posterity. In his relations with these friends Diderot was warmhearted, generous, somewhat absentminded, and slightly inclined to be self-righteous. These qualities were especially evident in his friendship with the difficult Rousseau, which ended in 1757. His friends greatly admired Diderot’s eloquent conversational powers. He loved to participate in the famous discussions at Holbach’s salon, where Horace Walpole found him “a very lively old man and great talker.“

Chronically neglectful of his wife, Diderot lavished greater affection on Sophie Volland, his liaison with her lasting from about 1755 until her death in 1784. His letters to her are universally regarded as one of the most fascinating and dazzling revelations of an era and a personality that the art of letter writing can provide.

Diderot doted on his only surviving child, Angelique, and to increase her dowry he sold his library in 1765 to Catherine II of Russia for 15,000 livres. The Empress stipulated that Diderot retain the use of the library and gave him 1,000 livres a year to improve it. In 1766, when Diderot was 53, she paid him a lump sum of 50,000 livres in advance for another half century of similar services. Diderot traveled to St. Petersburg in 1773-1774 to thank Catherine personally, and after this long and difficult journey his health was never robust. He died in Paris on July 31, 1784.

mavi