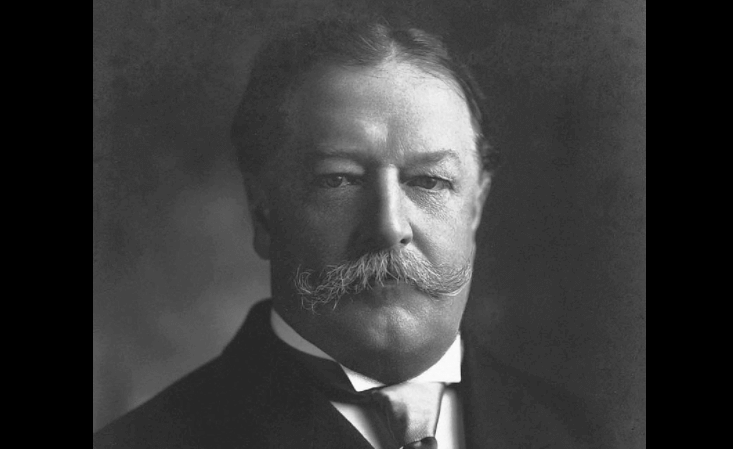

Who was William Howard Taft? Information on William Howard Taft biography, life story, political career and works.

William Howard Taft; (1857-1930), 27th president of the United States and 10th chief justice of the United States. He was the only man in American history to hold both offices. He esteemed his service on the Supreme Court (1921-1930) more highly than the presidency, having aspired to a judicial career from his youth. He recoiled from active participation in politics and had small talent for its vicissitudes, being too easy going and not enough of a fighter for the political arenas. Taft was not an innovator, either in the White House or on the bench. His record as chief executive was not without distinction, though it was blunted by the bitter political factional quarrel that ended his presidency after one term (1909-1913). He is chiefly remembered as the friend and then the political antagonist of the Progressive Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, with the effect that Taft is often supposed to have been more conservative than in fact he was.

Source : wikipedia.org

Early Career:

Taft was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on Sept. 5, 1857. His father, Alphonso Taft (1810-1891), was a lawyer who later served as secretary of war and as attorney general in President Ulysses S. Grant’s cabinet and then as ambassador to Austria-Hungary and Russia. Alphonso Taft’s wife, the former Louise Torrey, wrote of her son William a few weeks after he was born: “He is very large of his age and grows fat every day.” The words were prophetic, for Taft as an adult weighed 300 pounds or more, the heaviest of any president.

William grew up in Cincinnati, which was the political base for the Taft family through several generations. He graduated with distinction from Yale in 1878. In 1880 he graduated from Cincinnati Law School and was admitted to the bar. His first public office was as assistant prosecuting attorney of Hamilton county from 1881 to 1883. He was briefly the collector of internal revenue for Cincinnati in 1882. He practiced law in Cincinnati from 1883 to 1887, but already yearned for a judicial post. That goal was realized when he was appointed to an Ohio superior court vacancy in 1887. The next year he was elected to a term of his own, and this was the only office other than the presidency that he ever won by election.

In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison called Taft to Washington to the post of solicitor general. Two years later Harrison named him to the U.S. circuit court for the 6th district. Taft’s record as a state and federal judge was honest and competent, and he was receptive to the problems of labor in a nation that was just beginning to emerge from the influence of the laissez faire philosophy.

Taft’s attractive wife, the former Helen Her-ron of Cincinnati, whom he had married in 1886, was ambitious for her husband and a principal influence in persuading him to leave the law and the bench. But a larger opportunity did not come until the turn of the century.

The Philippines:

Taft began to gain national stature in 1900, when President McKinley appointed him head of a commission to terminate U.S. military rule in the Philippine Islands, which had become an American possession after the Spanish-American War. The appointment gave Taft his first opportunity to demonstrate ability as an administrator.

In 1901, McKinley named Taft the first civil governor of the Philippines. Taft’s governorship of the islands (1901—1904) was a high mark in colonial administration for any nation. Taft had, in marked contrast to the military, no trace of racial prejudice. He was warmly sympathetic to the problems of the Filipinos. He believed in giving them the widest possible degree of self-government and constantly worked toward that end. On the other hand, Taft was never deceived by the extremists among them. He recognized that the first steps toward the ultimate goal of independence was public education in the islands and the end of ownership of land by the Roman Catholic friars. Taft negotiated an agreement with the Vatican in 1903 whereby, with American financial assistance, the lands were sold in small parcels to the Filipinos.

Source : wikipedia.org

Secretary of War:

Theodore Roosevelt succeeded the assassinated McKinley as president in 1901. Roosevelt had known Taft in Washington during the latter’s service as solicitor general. Though different in temperament—Roosevelt was dynamic and impulsive, Taft restrained and judicial—they became close personal friends and political allies. Roosevelt twice offered Governor Taft a place on the U.S. Supreme Court, but Taft declined, pleading that his work in the Philippines was not finished.

But Roosevelt had come to regard Taft as his eventual successor and became convinced that he needed him in his cabinet. Taft accepted the post of secretary of war with the understanding that he could continue to oversee Philippine affairs from Washington.

Taft observed with some accuracy that he had “no aptitude for managing an army,” but the generals took care of that matter. The next four years were crowded and, all in all, successful. The secretary of war became the administration’s “trouble shooter” at home and abroad. Between 1904 and 1908 he had direct charge of the construction of the Panama Canal. In 1906, when revolution threatened Cuba, he brought a degree of peace through negotiations. In Tokyo in 1907, he improved Japanese-American relations strained by the abuse of Japanese immigrants in California.

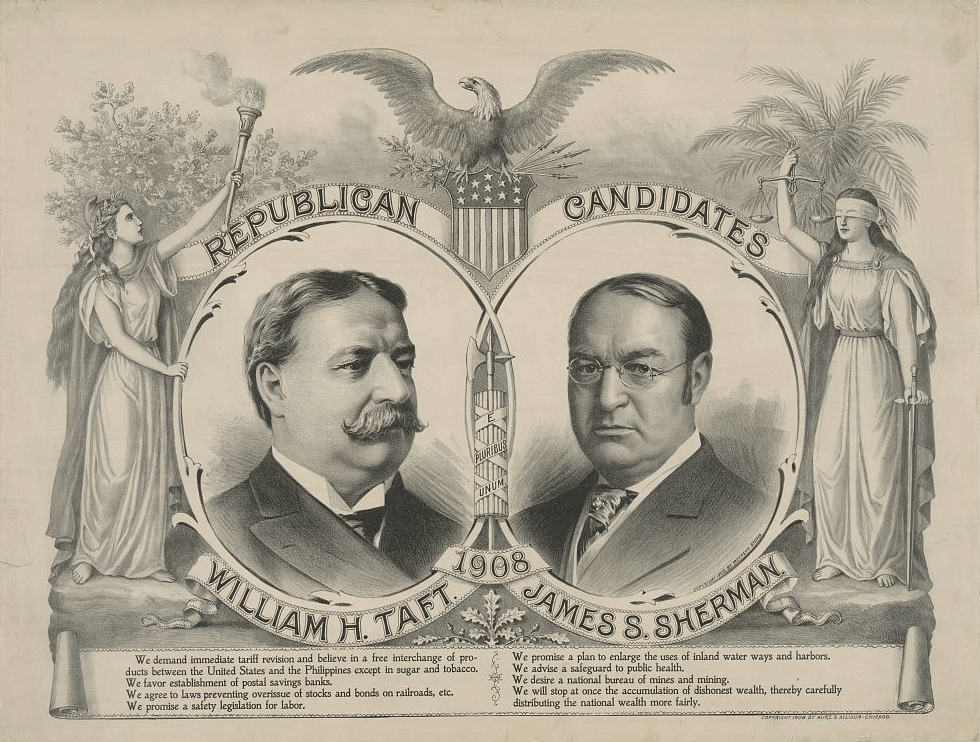

1908 Taft-Sherman poster (Source : wikipedia.org)

President:

“Politics, when I am in it, makes me sick,” Taft wrote to his wife in 1906. The secretary of war initially had no desire to run for president, but on Roosevelt’s demand and with the urging of his wife and brothers, he accepted the Republican nomination in 1908. Benefiting from the popularity of the Roosevelt administration, Taft defeated William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic candidate, by an electoral vote of 321 to 162 and a popular vote of 7,679,114 to 6,410,665. His inauguration on a storm-tossed March day in 1909 presaged four unhappy years in the White House.

The new President inherited widespread demands for a lower tariff. He accepted the compromise Payne-Aldrich Act ( 1909), a truly downward revision that satisfied neither big business nor the Progressive Republicans. Taft, with an ineptitude that so often marked his public utterances, called it the best tariff in history. The President negotiated with Canada an agreement that promised relatively free trade between the two countries, only to have Canada ultimately reject it.

Vigorously enforcing the Sherman Antitrust Act, Taft’s attorney general, George Wickersham, initiated twice as many antitrust suits against big corporations as had the previous administration, but Roosevelt, not Taft, is remembered as the “trustbuster.”

Conservation had a friend in Taft. Yet he properly supported his secretary of the interior, Richard Ballinger, against the somewhat fanatical Gifford Pinchot, chief of the Forest Service and loyal to Roosevelt. Pinchot had accused Ballinger of favoring private interests. Taft dismissed Pinchot. Ballinger, unable to recoup his reputation though unjustly charged, resigned.

Taft further alienated the Progressives by declining to side openly with the congressional insurgents opposing the dictatorial rule of the speaker of the House, Joseph G. Cannon. But, then, neither did Roosevelt.

On the plus side, the Taft administration saw the creation of the postal savings system and the parcel post, the establishment of a separate Department of Labor, and the admission of Arizona and New Mexico, the last of the 48 contiguous states. Constitutional amendments providing for the direct election of senators and for a federal income tax passed Congress and went to the states for ratification.

The Democrats captured control of the House in 1910, and Progressive Republicans looked to Roosevelt for their presidential candidate in 1912. Roosevelt, swinging farther to the left while Taft watched with alarm, was soon opposing the man whose nomination he had effected four years earlier. Taft felt heartbreak and despair when Roosevelt entered the contest for the 1912 presidential nomination. Taft did win renomination, but by “steamroller” methods. Roosevelt, loudly declaring that the nomination had been stolen from him, ran as an independent candidate for president. The result was the election of the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson. Taft ran third in the election, carrying only Utah and Vermont. He left office without due recognition for much that had been accomplished.

Chief Justice:

Taft retired to serve as Kent professor of law at Yale University with dignity and grace. He was then joint chairman of the National War Labor Board during World War I. The board had little power to settle labor disputes, but Taft’s 14 months in the post were an important educational experience. He came into closer contact with organized labor than ever before. It is possible that the knowledge he gained influenced some of his opinions as chief justice.

When Chief Justice Edward D. White died in 1921, President Warren G. Harding elevated Taft to the office he had long coveted. The court was badly divided when the new chief justice took his place. Taft’s greatest service lay in bringing more harmony and greater efficiency to the court rather than in outstanding contributions to judicial knowledge. He helped effect passage of an act of Congress permitting the Supreme Court greater discretion over the cases that came before it.

The chief justice never permitted personal opinions to influence him. Although he had not favored prohibition, he stood for strict enforcement of the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, which enforced prohibition. For Taft, law was law, whether it worked or not.

In other decisions, Chief Justice Taft rejected congressional efforts to impose controls on child labor through taxation; declared that the stockyards industry was national in scope and open to federal regulation; and sustained the president’s right to remove executive appointees without the concurrence of the Senate.

But Taft’s principal interest was in accelerating the work of the courts. To this end his contributions were major. Dissenting opinions were a possible cause of delay, and he shrank from all of them, including his own. “I would not think of opposing the views of my brethren,” he declared in 1927, “if there is a majority against my own.” The remark well sums up Taft’s philosophy regarding courts and judges.

Heart disease forced Taft to retire from the court on Feb. 3, 1930, and a month later, almost as if this surrender of the work he loved had sapped his remaining strength, he died in Washington, D.C., on March 8, 1930.

In addition to his father, members of Taft’s family who achieved distinction included his stepbrother, Charles Phelps Taft (1843-1929)—the son of his father’s first wife—who was the successful publisher of the Cincinnati Times-Star-, and his older son, Robert (1889-1953), a leader of the Republican party and elected three times to the U.S. Senate.