Who was Wilfrid Laurier? Information on prime minister of Canada Wilfrid Laurier biography, life story, and political career.

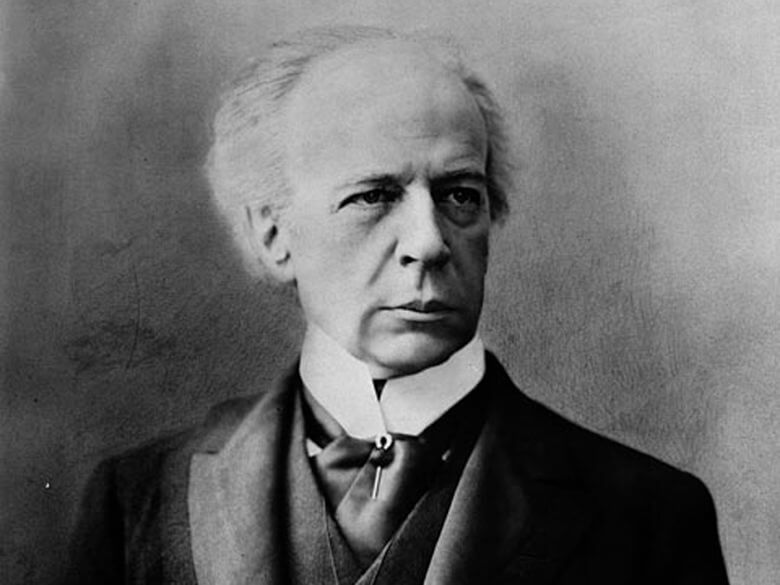

Wilfrid Laurier; (1841-1919), prime minister of Canada (1896-1911), and leader of the federal Liberal party (1887-1919). A man of distinguished presence, combining eloquence with great personal charm, Laurier was a force for unity through the early years of the Dominion. As its first French-Canadian prime minister, he presided over 15 crucial years of national development.

Wilfrid Laurier

Early Life:

Laurier was born in St.-Lin, Quebec, on Nov. 20, 1841, and was baptized Henri Charles Wilfrid. Prepared by a village schooling in French and English, he completed a seven-year classical course at the ecclesiastical college in L’Assomption and went on to McGill University for a degree in civil law. In 1864 he began practice as a barrister in Montreal, but a breakdown in his health forced him to move in 1867 to Arthabaska in the Eastern Townships.

As a French Canadian Liberal, or Rouge, Laurier first opposed Confederation, but he accepted it when it came in 1867 with the cool pragmatism that characterized his whole life. Gradually he became convinced that if provincial autonomy could be maintained, safeguarding the I educational, religious, and cultural identity of French Canada, the federal union was workable.

On Jan. 22, 1874, after three years in the provincial parliament of Quebec, Laurier was elected to the Dominion Parliament. Here he was I speedily recognized as a principal spokesman for Quebec in federal affairs. Within Quebec, he was involved in a struggle against Catholic ultramontanism, which equated political with religious liberalism and sought to silence both.

Party Leader:

In 1887, at the insistence of Edward Blake, who was retiring, Laurier was named to replace him as leader of the federal Liberal party. Laurier was dubious about accepting the position because he was a French Canadian and a Catholic in a country predominantly English and Protestant. Yet, though he began badly with an ill-conceived campaign in favor of tariff reciprocity with the United States, he was never shaken or even seriously threatened in his position. His ability to control men and shape a party was soon demonstrated. After the death of Sir John A. Macdonald in 1891, the Conservative party declined, and in the election of 1896, Laurier came to power at the head of the Liberals.

Laurier’s Prime Ministry:

The great issue of the campaign had been the question of separate schools for the French and Catholic minority in Manitoba. Laurier took the position that in abolishing such schools the province was within its rights, because education was a provincial matter. The federal government, in his view, could not coerce; it could only seek by agreement with the province to prevent injustice to a minority. Such an agreement, providing for a measure of separate education, was eventually concluded. It was one of the great compromises, wholly satisfactory to no one, by which he sought to dull the national conflict between French and Fnglish. Moreover, by upholding provincial autonomy for Manitoba he also upheld it for Quebec.

The first decade of the 20th century was marked by a great flow of immigration into Canada. The government encouraged it by every means, and most notably in the agricultural development of the western prairies. Along with new settlement, and with the industrial growth of the country generally, went extensive plans for a second transcontinental railway and eventually a third. Begun in buoyant times and with unlimited confidence, the railways involved duplication and resulted in an accumulation of fixed charges that eventually saddled the country with two nearly bankrupt railways. Laurier’s railway policy, though much of it was later justified, was probably his most criticized undertaking.

In the meantime the questions of schools, language, and religion rose again with the creation of the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905. Here, when Laurier tried to obtain for the Catholic minority a little better arrangement than it had enjoyed in Manitoba, he was forced by a revolt in his cabinet to a humiliating reversal of policy. Catholic separate schools in Alberta and Saskatchewan became more strictly limited in their scope than those of Manitoba.

Imperial Policy:

Though he valued Canada’s connection with Britain, Laurier was firm for the autonomy of the principal dominions within the empire. In 1899-1900, when he authorized the raising and equipping of a volunteer contingent for service with British forces in the South African War, he was faced with an outcry that showed him the aversion of French Canada to taking part in far-off imperialist wars. From then on, he steadily resisted all attempts to centralize the administration of the empire or to establish imperial defense forces or imperial defense commitments. The development of his ideas was, rather, in the direction of such an association as the present-day Commonwealth.

The Navy and Reciprocity:

Though he declined firm commitments for imperial defense, Laurier, in 1909, established a separate Canadian Navy. It did not satisfy a growing imperialist element in Canada, who desired to make contributions to the Royal Navy. This element denounced the Canadian Navy as a useless “tinpot” force, and at the same time many French Canadians opposed it as a first step toward militarism, imperialism, and conscription for service in the empire’s wars. Both charges Laurier vehemently and effectively refuted, and the issue appeared to have been settled when another arose.

This was a new Reciprocity Treaty negotiated with the United States on what at first seemed very favorable terms. Opposition built up, however, from commercial, industrial, and railway interests who feared its long-range effects. The old cry rose that Canada was to be detached from the empire through a closer connection with the United States. Now the navy issue was revived, and many of the older discontents of French Canadian nationalism rose to the surface.

The Laurier government, going confidently to the country in the “reciprocity election” of 1911, found itself fighting on several fronts. It was denounced by French Canadian nationalists as a willing tool of imperialism and a servant of English interests. At the same time it was represented by the Canadian commercial and imperialist element as a dupe of the United States and a niggardly contributor to the empire in a time of need. In the midst of a darkening international scene Laurier’s conciliation and moderation failed him. In the election of 1911, after 15 years of power, he went down to defeat.

Leader of the Opposition:

Laurier remained a national figure, respected by all parties and of immense influence in the country. When world war came in 1914, the support of the 73-year-old leader of the Opposition was of great importance to Sir Robert Borden, the Conservative prime minister. It was given in full measure though Laurier’s position was difficult. French Canadians who were being asked to enlist for the empire’s service were also then having their educational rights curtailed in Ontario and newly restricted in the Prairie Provinces. Laurier could do little to reduce this serious new wartime conflict. Nevertheless he lent his voice in support of recruiting, though he coupled his call to voluntary service with a pledge that conscription would never be introduced.

When conscription came, forced on Borden by the mounting demands of the war, Laurier was compelled to break with him. He declined to enter a union government, headed by Borden, including leading men of both parties, and pledged to conscription. He did not believe that conscription would be effective in a country almost stripped of manpower. More importantly, he was solemnly pledged against it to his own people.

With a wartime election called, many of his supporters turned against Laurier on the conscription issue. He was left with a mere rump to fight the election of 1917. In the outcome he was almost totally supported by Quebec and almost totally rejected by the rest of the country. Division had never been so great between French and English Canada, and a lifetime of work toward national unity seemed to have failed utterly.

Yet in the two years of life that remained to him the picture changed and old supporters returned. Different regions of the nation began to sense their mutual need of one another. When Laurier died in Ottawa on Feb. 16, 1919, it was as the leader of a restored party who was even then in the process of choosing his own successor.