Who is Thomas Cranmer? Information on Thomas Cranmer biography, life story, works and death. What did Thomas Cranmer do?

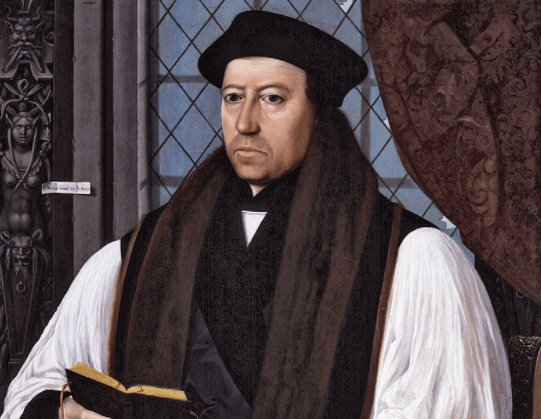

Thomas Cranmer; (1489-1556), English religious reformer and archbishop of Canterbury. He was born at Aslockton, in Nottinghamshire, England, on July 2, 1489, the son of a village squire. Cranmer was educated at Cambridge University, receiving his B. A. in 1511. Proceeding to his M. A. in 1514, he was made a fellow of Jesus College, a post he was forced to relinquish because of his marriage shortly thereafter. Readmitted to his fellowship upon the death of his wife, he was ordained about 1520 and devoted himself to the study and teaching of Scripture and theology, receiving his bachelor of divinity degree in 1521 and his doctorate in 1526.

Henry VIII’s Reign:

A ferment for reformation agitated Cranmer’s Cambridge, and the influence of the writings of Erasmus and Luther was strong. Though not so ardent for reform as others of his circle, Cranmer had set himself against papal supremacy, and his Biblical and patristic studies were leading him toward a further break with the church’s traditional positions. In 1529, when the negotiations for a papal annulment of the marriage of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon seemed fruitless, Cranmer caught the King’s attention with his suggestion that the question of the validity of the royal marriage be referred to the universities of Europe. Henry VIII made him a royal chaplain and archdeacon of Taunton, sending him abroad in 1530 on a diplomatic mission to Emperor Charles V. While in Germany he secretly married a niece of the Lutheran reformer Andreas Osiander.

Source : wikipedia.org

Recalled in 1532, Cranmer was nominated by the King to the archbishopric of Canterbury, vacant by the death of Warham. He accepted with sincere reluctance, moved chiefly by his opposition to papal authority and his firm belief in the principle of royal supremacy in the church. He was consecrated on March 30, 1533. Two months later, while the parliamentary statutes that separated England from the papal authority were being devised and passed, Cranmer pronounced the King’s marriage null and void. Declaring the union of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn to be lawful, the archbishop stood godfather to their daughter, the future Queen Elizabeth I, at her baptism on Sept. 10, 1533.

As long as Henry VIII lived, there were no no significant doctrinal or liturgical changes in the English church, though Cranmer was ready to make further moves in reformation. He was influential in the composition of the Ten Articles of 1536, the first articles of faith issued by the Church of England, and the Bishops’ Book of 1537, an exposition of doctrinal questions and teachings. He furthered the preparation of the Bible in the vernacular and encouraged conferences between English churchmen and Lutheran divines. He disapproved of the Act of the Six Articles of 1539, a penal statute aimed at halting attacks upon traditional doctrines and practices, and he had little enthusiasm for the King’s Book of 1543, a set of doctrinal articles illustrating the conservative reaction of Henry’s last decade.

Edward VI’s Reign:

Upon the accession of the young Edward VI in 1547, Cranmer bore the chief responsibility for the reforms that altered the English church. The marriage of the clergy, the repeal of the heresy laws and the Six Articles Act, the destruction of images, shrines, and altars, and the abolition of a number of ceremonies and usages all met with his approval. However, Cranmer deplored the influence in church affairs exercised by some of the King’s councillors, particularly, after 1551, by the unscrupulous Duke of Northumberland (John Dudley).

Cranmer’s greatest and most enduring work was the production of the first Book of Common Prayer, imposed by the Act of Uniformity of 1549. A revision, the Prayer Book of 1552, was subsequently done by Cranmer. The English Prayer Book, immensely influential for more than four centuries, reveals Cranmer’s profound spirituality and his incomparable mastery of liturgical prose. The doctrines embodied in its services reveal also the extent to which Reformation influences had modified some traditional doctrines in this period. Cranmer’s Forty-two Articles of 1553 (the basis of the famous Thirty-nine Articles) had scarcely been published when Edward VI was succeeded by Mary I, who returned England temporarily to the old order in the church, including» formal recognition of papal authority.

Death:

Cranmer was imprisoned for treason for his acquiescence in Northumberland’s plot to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne, but his life was temporarily spared, largely because the Queen was determined to see the religious changes of her brother’s reign discredited by the condemnation of their chief author as a heretic. Tried, degraded from holy orders, and sentenced to death, Cranmer responded to severe pressures to recant by issuing several repudiations of his former convictions. They were mainly the product of the dilemma of a conscientious man whose belief in royal supremacy was sorely shaken when his monarch used that power to obliterate it in favor of papal supremacy. On the day of his execution at Oxford, Cranmer repudiated his recantations with great courage and met his end at the stake, on March 21, 1556, with the fortitude of a martyr.