What did Leo Tolstoy write? Information on Leo Tolstoy works, books and career. Early and later fiction. Fiction after his conversion.

Early Fiction.

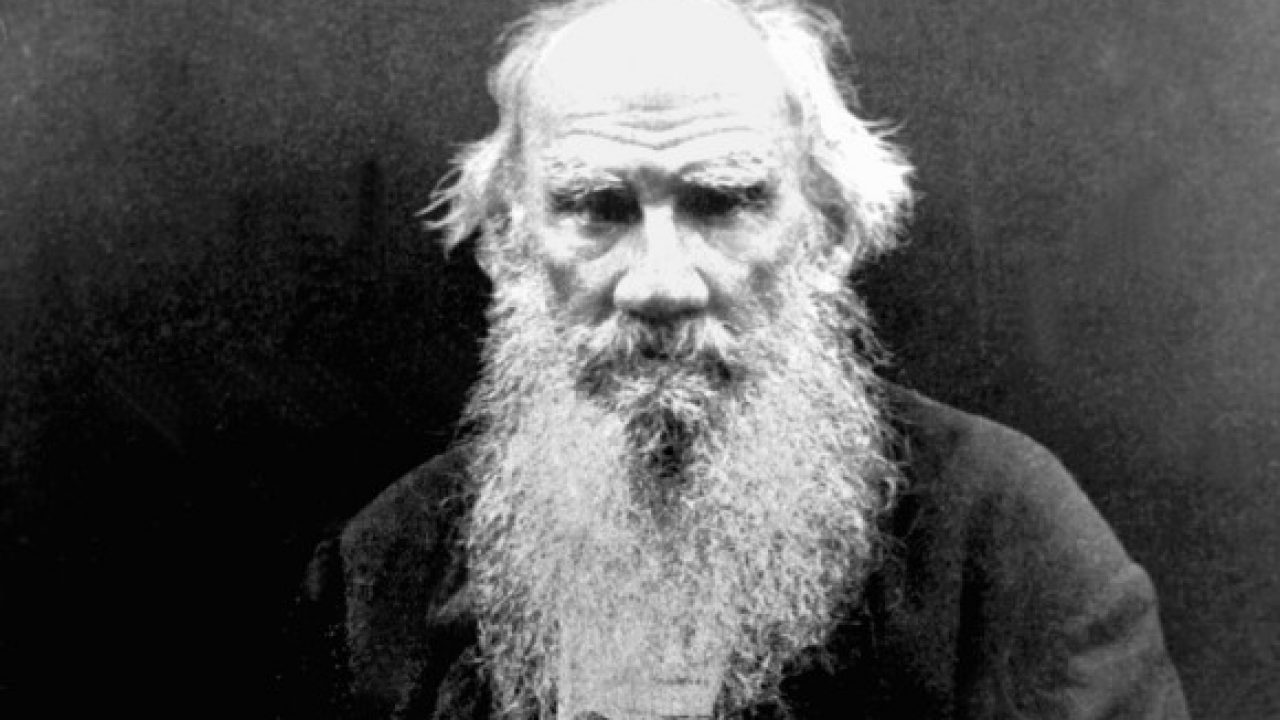

Whatever Tolstoy’s fame as a moralist and thinker may be, his enduring reputation rests largely on his magnificent literary productions. The early development of his creative art seems to have been a matter of trial and error rather than initial imitation. That is, though he continued and made quite his own the tradition of classical Russian realism begun by Pushkin, there is no marked dependence on preceding Russian authors. He may, however, have been somewhat influenced at the beginning by such foreign writers as Rousseau, Sterne, Stendhal, and later, Thackeray.

A suggestion of his method and approach may be found in the acute self-examinations in Tolstoy’s early diary. This kind of searching analysis of the conscious and even subconscious motivation of thought and action appears in his first literary fragment, A History of Yesterday (1851), and also in Childhood, and its sequels Boyhood (1854) and Youth (1857). He was skillful in evoking childhood memories, which, when recalled with feeling—as they are—seem infallibly true and charming. He wrote, he said, from the heart and not from the head. Although these initial efforts draw heavily upon personal recollections, there is much sheer invention.

Compared with the work of other major writers, Tolstoy’s fiction is unusually autobiographical. This fact is no reflection on his considerable imaginative powers, since the reality of recorded experience and observation that he transformed into art is rendered doubly effective by keen psychological analysis and the meticulous selection of significant detail.

The early Caucasian short stories, A Raid (1853), The Woodfelling (1855), and The Memoirs of a Billiard-Marker (1855), based on Tolstoy’s actual experiences in that region, seem to be told merely for their own sake as interesting narratives. But in the short pieces that followed— Lucerne (1857), Albert (1858), Three Deaths (1859), and Family Happiness (1859) — he concentrates, in a didactic manner, on moral problems, notably the. baseness and vulgarity of the cultured man. The large degree of subjectivism in most of the tales, however, is largely avoided in the stories Two Hussars (1856) and Polikushka (1863), in which the evil influences of a materialistic society are artistically suggested. It is also avoided in Kholstomer (1863; jaublished 1886) a satire on human beings from the point of view of a horse, in which the noble animal’s natural life is represented as superior to man’s artificial existence. The contrast between natural man and man the spoiled product of civilization is given wonderful artistic expression in The Cossacks (1863), a short novel that rounds out Tolstoy’s early literary period. The central figure, Olenin, a member of sophisticated society, proves to be no match for the natural, freedom-loving, uninhibited Cossacks, such as old Daddy Yeroshka, one of Tolstoy’s most memorable creations.

Later Fiction.

Tolstoy’s mature art emerged in all its power in his first full-length novel, War and Peace, which has frequently been acclaimed by distinguished writers and critics as one of the greatest novels ever written. The work, which is essentially a historical novel, is set in the years between 1805 and 1814 and involves the fortunes of five families: the Rostovs, Bolkonskys, Bezukhovs, Kuragins, and Drubetskoys. Their interrelationships are vividly portrayed against a vast background of Russian social life and the titanic struggle of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. Tolstoy uses the novel to expound his philosophy of history and to theorize on war, thus introducing a didactic quality that may be considered an artistic flaw. There is no doubt that it is the incredibly rich variety of life portrayed, rather than the historical forces integrating it in the grand design of the work, that primarily interests readers.

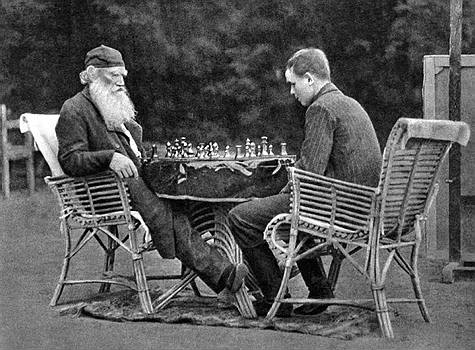

Tolstoy always contended that it was more difficult to portray real life artistically than to invent fiction, and many of the characters in War and Peace are based on members of his family or on friends. Certainly within this novel, life itself is embodied in unforgettable scenes and in scores of vitally realized men and women. None of his other works so justifies his conviction that the aim of an artist is to compel one to love life in all its manifestations. War and Peace reveals his uncanny ability to make the ordinary and commonplace seem strange, new, and exciting.

Tolstoy’s second full-length novel, Anna Karenina, is similar to War and Peace in narrative method and style; but it presents a striking contrast to the life-loving optimism of the earlier work, and its plot has more inner unity. Anna’s tragedy unfolds slowly and remorselessly before a large audience of the social worlds of two capitals in the 1860’s. Nearly all the fully-drawn characters, including the fascinating members of the Oblonsky and Shcherbatsky families, are involved in one way or another with the fate of the two star-crossed lovers, the adulterous Anna and Vronsky, who are effectively compared with the happy lovers, Kitty and Levin. While Tolstoy’s characters are always brilliantly and perceptively portrayed, in Anna Karenina they are subjected to more intensive psychologizing and to a deeper, more searching moral probing. The novel is one of the great love stories of the world, and it is a measure of the moral balance preserved in the portrayal of the beautiful but tragically erring heroine that he persuades readers to judge her severely but at the same time with compassion.

Fiction After His Conversion.

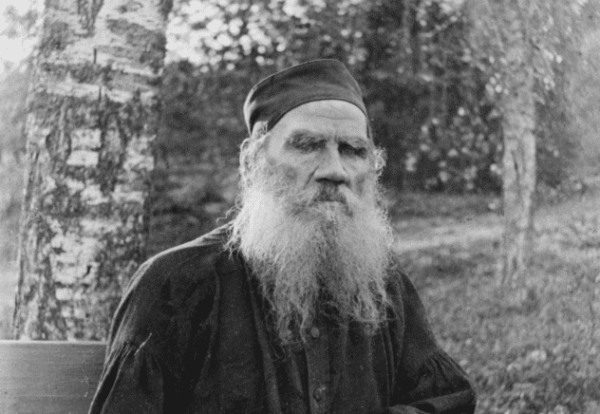

Tolstoy’s spiritual crisis overtook him before he finished Anna Karenina. After his conversion he tended to devote much of his energy to books and articles on religious, moral, political, and social themes. In 1897, however, he finished What Is Art? (1898), an elaborate effort to propound an aesthetic system that would accord with his new moral philosophy and understanding of man’s relation to life. In it he developed the thesis that the best literary art is that which “infects” the largest number of people with the loftiest feelings of love and compassion. In the literary works he wrote after his spiritual crisis, he attempted, with few exceptions, to conform to this thesis. At the same time, with inexorable consistency, he relegated his great works of art written before this to the category of “bad art.”

Among various short tales done in the new manner, in a bare style and designed to appeal to simple folk as “good universal art,” are such little masterpieces as What Men Live By (1881), Two Old Men (1885), Evil Allures but Good Endures (1885), How Much Land Does a Man Need? (1886), and Three Questions (1903).

Tolstoy’s special concern with sex in his new faith in terms of chastity is powerfully reflected in The Devil (1889; published posthumously, 1911—1912), a story, based on an incident in Tolstoy’s life, of a husband’s struggle to overcome his lust for a pretty peasant girl. The Kreutzer Sonata (1890) combines an artistic study of a husband’s jealousy with a didactic attack on society’s sexual education of youth, which he regarded as mendacious.

In some of the works of his later period, Tolstoy came closer to the style, if not the subject matter, of his earlier fiction. Among these works are three outstanding stories: the incomplete Memoirs of a Madman (1884; published posthumously, 1911-1912), a rather thinly disguised fictional treatment of the oppressive fear of death that Tolstoy himself had experienced before his conversion; The Death of Ivan llich (1886), a remarkable account of the hero’s mystical conversion when, confronted by death, he discovers the inner light of faith; and the exquisite Master and Man (1895), a different treatment of the same theme of mystical illumination, that reminds one of Tolstoy’s statement that without simplicity there is no grandeur in art.

Tolstoy’s only full-length novel during his old age, Resurrection (1899), marks a return to the adorned style and narrative manner of Anna Karenina. It concerns the involved relations of the nobleman Nekhlyudov with Katya Maslova, whom he seduces and deserts. Turned out of her home, she is driven to prostitution. Later Nekhlyudov serves as a conscience-stricken juror at the trial in which she is convicted of a crime she did not commit. The work has some outstanding scenes and fine characterizations, but it is marred artistically by its moral preaching and overt satire of social and religious abuses.

Major Nonfiction Works.

Out of Tolstoy’s great spiritual crisis emerged an extensive body of writing that is a tangible part of his literary experience and reveals his importance as a thinker whose ideas have not lost their significance today.

In A Confession (1882), one of the noblest utterances of man, he records the unique and overwhelming inner turmoil of a person extremely perplexed by life’s most difficult problem—the relation of man to the infinite. It was followed by An Examination of Dogmatic Theology (1891), a vigorous attack on the church; What I Believe (1884), a systematic presentation of his views on religion; What Then Must We Do? (1902), his account of the Moscow slums, based on an early experience as a census worker, and an elucidation of the causes and cure of social and economic ills; and The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894), the fullest statement of his Christian anarchism and his belief in nonresistance to evil.

These lengthy works, along with many shorter essays, often attack specific governmental and social practices. The use of intoxicants and tobacco is deplored in Why Do Men Stupefy Themselves? (1890). Both this work and I Cannot Be Silent! (1908), his protest against the execution of revolutionists, are filled with the passionate intensity of his new faith and demonstrate his unusual intellectual capacities and his skill as an astute and convincing logician.

In Tolstoy’s search for truth, a compulsive need to achieve the ultimate rational explanation sometimes led him to push theory to the limits of absurdity. However, he never failed to place his faith in the moral development of the people as a final answer to what he regarded as the universal oppression of the many by the few. The ideal human condition, he insisted, must inevitably depend upon the growing moral perfection of each individual through the observance of the supreme law of love and the consequent rejection of every form of violence.

Posthumously Published Fiction.

Tolstoy withheld publication of a number of works written during the latter part of his life. The best of these were all published in 1911-1912, after his death. Hadji Murad is a superb short novel describing a brave Caucasian chief who deserts to the Russians and is killed while trying to see his son in secret. Father Sergei is about an aristocrat who conquers his spiritual pride and becomes a hermi-monk. After the Ball tells the story of a youth who loses his passion for the daughter of a colonel after the latter orders a soldier clubbed through the ranks for a military offense. The False Coupon is a fictional moralistic study of how human goodness can develop out of evil. And Alyosha Gorshok, perhaps Tolstoy’s last short story, is a perfect artistic gem about a peasant drudge who finds complete contentment in life through service to others.

Plays.

Drama was a form of art to which Tolstoy was devoted but in which he was not always successful. His finest play is The Power of Darkness (1887), a realistic tragedy of peasant life that reveals the power of evil to beget fur» ther evil. The Fruits of Enlightenment (1889) is a pleasant comedy that pokes fun at the foibles of aristocratic society.

Two plays were published in the posthumous edition of 1911-1912. These are The Light Shineth in Darkness, in which the hero’s inability to persuade his family of the rightness of his unconventional beliefs echoes Tolstoy’s own situation, and The Living Corpse, a convincing psychological dramatization of the strange experience and loving sacrifice of a drunkard. The latter play is suffused with a kindly tolerance of human waywardness and is devoid of the moralizing element that detracts from the enjoyment of some of Tolstoy’s works written during his last years.