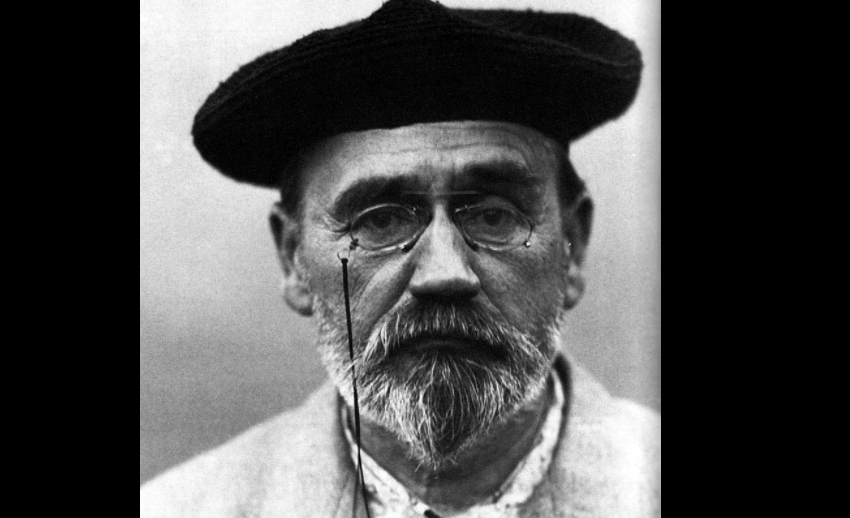

Who was Emile Zola? Information on French novelist Emile Zola biography, life story, works, books and writings.

Emile Zola; French novelist: b. Paris, France, April 2, 1840; d. there, Sept. 29, 1902. His development as a writer began during his youth at Aix, where he and his friend Paul Cezanne started out by imitating the romantics. His widowed mother wanted him to study law, but he failed to win his baccalaureate and in 1860, after two months as an ill-paid clerk on the Paris docks, abandoned himself for a year and a half to the garret life of an impoverished poet. This attempt at verse ended in failure and was followed by a period of reaction to romanticism and further growth in the direetion of realism.

As a publicity chief at Louis Christophe Hachette’s bookshop, he learned what made writing sell. As a vigorous literary columnist and art critic on Cartier de Villemessant’s newspapers, he mastered the techniques of sensational journalism. In 10 formative years he wrote numerous short stories and essays, 4 plays, 2 long pieces of commercial fiction, and 3 serious novels—La confession de Clauae (1865), Therese Raquin (1867), and Madeleine Ferat (1868).

Source : wikipedia.org

Influenced by Honore de Balzac, Stendhal, Gustave Flaubert, and Hippolyte Taine, Zola formulated his aesthetic principles, including his definition of art as “nature seen through a temperament.” He further expressed his belief that true artistic originality can best be achieved only by a rejection of tradition and a total submission to the life of one’s own times, and he was convinced that science offers the writer a superior method of approaching reality. In 1868, armed with these ideas, he submitted to his publisher the plan for a group of novels, Les Rougon-Macquart, portraying the fortunes of a family under the Second Empire and through this frame the whole turmoil of his age. At first limited to 10, the series ultimately comprised 20 volumes, ranging in subject from the world of peasants and workers to the imperial court, and in type from shocking exposes to lyrical fantasies and sustained epics. Yet, although he liked to astonish the public with his virtuosity, his method of composition’changed little over the years. First methodically assembling his research data, plot ideas, and character sketches under separate analytical headings, he then combined all this material in chapter plans with a complex art anticipating the techniques of film montage. Finally, with this scenario to guide him in the writing stage, he was free to concentrate on his style, which was remarkable for frequently rhythmic repetition, visual impressionism, and force.

Starting with the publication of L’assommoir (1877), a tragic study of life in the Paris slums, Zola became world famous, bought an estate at Medan, and attracted imitators and disciples. From 1879 to 1882, to consolidate his success, he waged a lively publicity campaign supporting naturalism. Inspired by Claude Bernard’s Introduction â la medetine experimentale (1865), he even wrote a treatise (Le roman experimental, 1880) picturing the naturalist author as a scientific observer following his fictional human guinea pigs through lifelike situations and thereby verifying certain psychological and social hypotheses. Yet, despite such efforts to build a public image of himself as a scientist, he was at his best, not when trying to apply specific scientific or pseudoscientific theories, but when giving imaginative expression to the new subjective vision of reality that modern science and technology had helped shape.

Essentially, like other great realists, Zola was an “illusionist” who excelled at imposing his intuition of the world under the guise of plain, unvarnished fact. This method may be seen in Germinal (1885), generally considered one of his finest works. The first major novel on a strike, it may be appreciated either as a factual social document or as a prose epic, a lurid yet sublime “poem,” in which his research notes on class warfare and labor conditions in the coal mines grow into dreamlike symbols and Dantesque descriptions often bordering on hallucinations. As elsewhere in his novels, objects are brought to monstrous life, animals assume human traits, crowds become forces of nature, and individual characters are transformed into types, allegories, and symbols. Underlying this synthesis of realism and symbolism, which is the triumph of Zola’s art, are the poetic themes which provide the Rougon-Macquart novels with their deepest unity: above all, a sense of cosmic upheaval, of world destruction and renewal involving a cyclical view of history and a materialist philosophy in which little remains of the Christian-humanist tradition. It is a philosophy in which, as Jules Lemaître said, “men appear like waves on a sea of darkness and unconsciousness.”

After the enormous Rougon-Macquart project, Zola undertook to expound his social gospel based on a creed of hard work and justice in a trilogy (Les trois villes, 1894-98) and an unfinished tetralogy (Les quatre evangiles, 1899-1903) but never again attained the power of such masterpieces as L’assommoir and Germinal. On Jan. 13, 1898, he went to the defense of Capt. Alfred Dreyfus by publishing in L’aurore a letter, “J’accuse,” pointing out irregularities in Dreyfus’ trial and making charges that practically forced the government to prosecute him, an expedient that achieved its purpose in reopening the Dreyfus case and led to the complete vindication of that officer. In February 1898 a verdict imposing imprisonment and fine was brought against Zola, but it was quashed by the Cour de Cassation on April 2. A second trial was called and Zola, his purpose accomplished, decided not to appear and went to England, where he remained until an amnesty permitted his return to France. He died of asphyxiation caused by fumes from a blocked chimney in the bedroom where he was sleeping.

Source : wikipedia.org

At Zola’s funeral, Anatole France declared, “He was a moment of the human conscience.” Zola had been repeatedly refused admission to the Academy, and after his condemnation in 1898 he was removed from the roll of the Legion of Honor, but in 1908 his remains were transported to the Pantheon. Although still famous chiefly as the main exponent of literary naturalism, he has undergone since about 1950 a general critical reevaluation emphasizing his powerful imaginative qualities.

mavi