In-depth and detailed information on ancient Egyptian art and architecture that affected the whole world. Ancient Egypt : Architecture and Art

Egyptian houses, palaces, and forts were built of wood and mud brick, but temples and tombs, which were intended to last for eternity, were built of stone. Often temples and tombs had huge statues and reliefs, painted in minute polychrome. Architecture in stone copied stylistic elements that had evolved in prehistoric structures made of lighter materials, such as reeds, papyrus, palm fronds,, and mud. Typical stylistic elements were the cavjstto cornice, presenting a concave edge (but originally a straight slanted edge) in sectional outline; torus, or cylindrical, molding beneath the cavetto cornice; and the kheker frieze, derived from the ornamental bunding of the upper ends of vertieal stems in a wickerwork wall.

Source : pixabay.com

ARCHITECTURE

In Egypt’s rainless, hot climate, settlements were built along the Nile or a canal and expanded northward into the prevailing wind. Usually they were loeated high enough to avoid being flooded when the Nile rose each year. Little can be seen of the earliest villages, which now lie buried deep under layers of sediment, except for those on the outskirts of the desert, such as Merimde (about 4500 b. c.) and Helwan. The picture they present is complemented by representations of huts and cabin boats on bone labels for house-hold vessels and on painted pottery. The archaic hieroglyph n[wt, “city” (3200 b. c.), shows streets crossing one another at right angles, and this oıthogonal pattern, with streets running north-south and east-west, appears in the cemetery of l4th dynasty nobles at Giza, obviously copying the plan of a town.

Urban Development.

The orthogonal Street pattern characterized the pyramid cities—planned settlements built in the desert near the royal pyramids to accommodate the artisans and priests associated with the construetion of those monuments. The pyramid city at Lahun, built by the 12th dynasty King Senusert II, could accommodate 8,000 people. It must have been surrounded by a square wall 370 meters (1,200 feet) on each side and accessible from a gate in the south side. The town was divided by an internal wall into an eastern district and a much smaller western one. Main streets 8 meters (about 9 yards) wide ran north-south, crossing secondary ones half as wide running east-west. The blocks thus formed contained houses attached side by side and back to back. Nine mansions lined a special street in the town’s northeast corner.

The artisans’ village at Amarna East, 70 meters on each side, was similar in design. It had one type of house, measuring 10 meters by 5 meters, and the houses were attached side by side, one row to a block. The dwellings had a tripartite plan: front room (west), central columned hail, and back bedroom and kitchen (east). The orientation took full advantage of sunlight: in the morning the sun shone into the kitehen and bedroom; in the afternoon it shone into the front room.

Source : pixabay.com

Less regular was the smallest of the artisans’ cities, at Deir el-Medina. It was inhabited during the New Kingdom for four centuries and was enlarged twice. It must have been subjeet to municipal regulations, for it was found clean all the way down to bedrock.

Nothing is known about the ordinary villages, which must have grown organieally as have all villages in the Middle East. Towns were certainly more regular in design, if not strictly orthogonal, and the capital built by Akhenaten (Akhenaton) at Amarna in the I8th dynasty confirms this assumption. A system of three streets parallel to the Nile was interrupted by deep wadis (dry river courses) that divided the builtup area into three separate quarters: the central city, containing temples, palaces, and administrative buildings; and two residential quarters, north and south.

Amarna mansions, built on a tripartite plan, stood on large plots that also contained grain bins, storehouses, a chariot house, a separate kitehen and baking oven, a garden, and often a chapel to the Sundisk. Brick was the basic material for walls and floors; limestone, for lintels and column bases; wood, for columns, doors, and windows. The main building had a central columned hail, higher than the other rooms and lighted by clerestory windows. An upper story, set back slightly, extended over the front room of the ground floor.

Rural resthouses, mansions, and multistoried urban houses were depicted in the tomb paintings of high officials of the New Kingdom in Thebes West. Above the ground floor was the main floor, conspicuous for its large mullioned windows with variegated patterns. An upper floor had smaller windows, and on the terrace, which was surrounded by a palm-frond parapet, were grain bins and other utilities. Façades of pink, ivory, and yellow, with horizontal red stripes, lent color to the drab mud streets.

The three-storied mansion of Thutnefer, who lived in Thebes in the reign of Thutmose III, was depicted in eross section in his tomb. The basement was used for loom-weaving. The ground floor, by far the tallest, and the upper floor both had a central column and were accessible from a staircase rising in an independent well to the terrace, where grain was stored and meat hung to dry.

Source : pixabay.com

Palaces.

Of the palaces of the Old Kingdom little is known except for the entrance gateway, pictured as a heraldic motif in the serekh, or hieroglyph enelosing the Horus name of the pharaoh.

Remains of several New Kingdom palaces are extant: four of Amenhotep III at Malqata, official and residential palaces at Amarna, and palaces in mortuary temples. In large palaces, as at Malqata, the throne hail assumed large proportions and was often duplicated in several audience halls, while in the residential quarters a long columned hail lined with harem suites preceded the pharaoh’s apartments.

Though palaces and mansions were built of mud brick, they were decorated with tasteful mural and floor paintings combining secular and religious scenes. Wooden columns were daubed red or painted with all the detail of the plant they imitated. Plaster garlands spread at the tops of the walls in Amarna mansions. In Malqata palaces large figures of princesses and of Amenhotep III on his throne were painted on the walls, with wooden birds projeeting above them. The floor simulated ponds teeming with fish and fowl, while the ceilings represented matwork, geometric pattems enelosing floral elements or bucrania, and birds treated in an impressionistic brush-work.

Cult Temples.

The cult temples were “eastles of god.” Their design borrowed the tripartite plan of the typical house as early as the Archaic Period, in the brick temple of Khentiamentiw at Abydos. In the wattle-and-daub shrines of Neith and Sobek, the naos, or room containing the sacred statue of the deity, was at the back of a eourt in which an emblem pole stood. At the entrance of the court were two standards, called neter (“god”), foreshadowing the flagstaffs fronting later, temples.

Cult temples of a special type without a statue or shrine were dedicated to the sun god Re by six pharaohs of the 5th dynasty on the plateau of the Western Desert south of Giza. Access was gained through a portal situated on a canal in the valley below. A causeway rose from this valley portal to the temple proper, where in a large court stood a squat obelisk on a massive base, preceded by a sun altar and two yards for slaughtering sacrificial animals. Wall reliefs depicted the various creative activities of the sun. The obelisk—perhaps symbolic of the sun’s slanting rays—was the link that conveyed the offering to the sun. A pointed stone called benben, similar to the pointed top of an obelisk, stood in the temple of Re at Heliopolis. Later there was one in the temple of the Sundisk, or Aten (Aton), at Amarna. This temple consisted of a columned foretemple (“House of Rejoicing”) preceding a series of six courts (“Meeting the Aten”) that were covered with numerous rows of offering tables.

Source : pixabay.com

The peripteral chapel appeared in the early 12th dynasty and in the New Kingdom. It consisted of a socle, or base, which carried roofed-over pillars and was accessible from two stair-ways, front and rear.

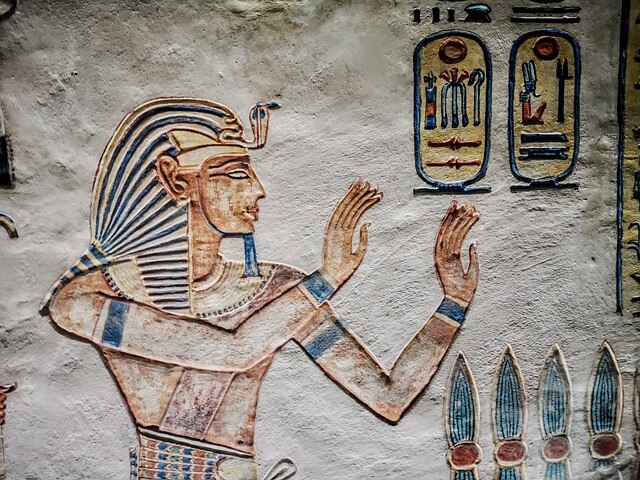

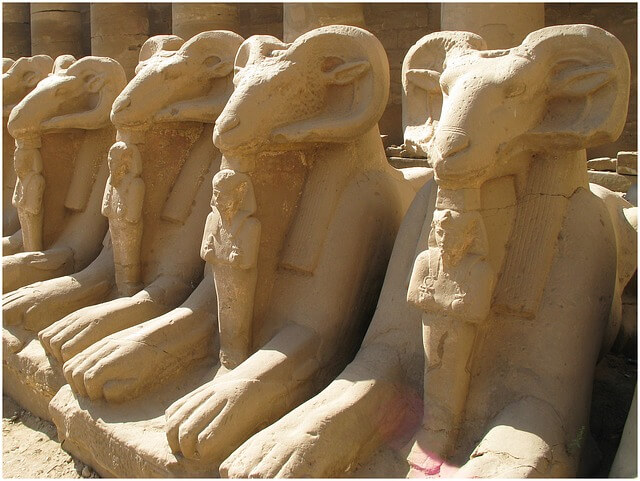

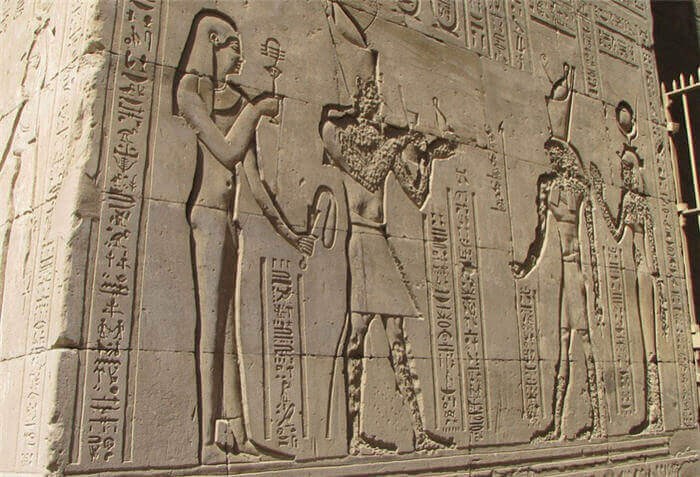

In the New Kingdom the typical cult temple, like those of Khonsu and Ramses III at Karnak, met the requirements of an ideal “house of god.” A street lined with sphinxes led from the landing quay or road to a pylon, the two rectangular towers of which flanked the gateway, each fronted by flagstaffs. In the larger temples two obelisks and colossal statues of Pharaoh stood on either side of the entrance. The “broad feast-court,” accessible to the populace, was surrounded on three sides by a eolumned portico and led to a hypostyle eolumned halL This was called the “hall of appearance,” and often two more halls preceded the sanctuary, or naos, and its surrounding rooms. The axial layout focused on the naos and its “living” statue of the god. Light and space decreased toward the rear of the temple as the floor level rose from the sunlit court to the dimly lit hypostyle and finally to the practically dark sanctuary. The intention was to inspire awe. All the walls and columns were built of stone. The façades were earved with sunken reliefs representing the triumphant pharaoh and his battles, and on the inside there were scenes pertaining to the ritual that was performed in each room.

Temples increased in size by a process of accretion, as ever larger pylons and courts were built in front of existing ones. The temple of Amun (Amon) at Karnak had six pylons. Occasionally the hypostyle had an open façade, as at Luxor, or was surrounded by a lower ambulatory on four sides, as in the Festival Hail of Thutmose III, or had a central nave that was higher than the side aisles, as in the temple of Amun at Karnak, foreshadowing the basilica. The cult temple was modified in the Ptolemaic period—as at Philae, Edfu (Idfu), Esna (Isna), and Dendera —with an open façade of columns with screen walls between them, and a large opening in the ceiling for light.

A special type of temple called a “birthhouse” developed to simulate the papyrus bush at Chemmis where Isis hid with her infant, Horus.

Mortuary Temples.

Built for the funerary ritual, mortuary temples were originally attached to the royal pyramids built in the desert. They abutted on the north side in the 3d dynasty and later on the east side, and were approached from a valley temple on a canal, by means of an inclined terraced causeway.

The massive plan and impressive well-polished granite pillars of mortuary temples built during the 4th dynasty at Giza were succeeded in the 5th dynasty by elegant plans and stylized floral columns. Profuse wall scenes narrated episodes from the life of Pharaoh. A terraced design was used in the llth dynasty by Mentuhotep II at Deir el Bahari (Deir el-Bahri), where the pyramid stood atop porticoed platforms and was not used for the burial. Hatshepsut, in the 18th dynasty, stretched the terraces and porticoes of her mortuary temple in the same semicircle of terraced cliffs, matching the natural formation most successfully.

Later Theban mortuary temples were dedicated to Amun, to the father of the deceased pharaoh, and to Horakhty.

Tombs.

To the Egyptian the tomb was his real abode, which he strove to prepare during his lif etime to secure an eternity of happiness. The tomb was to preserve the body from weather deterioration and from robbers, who were a constant danger because of the valuable funerary equipment that accompanied the burial. For greater security, the burial was gradually placed deeper underground. In time, royal prerogatives were available to the highest classes, including the stellar destiny whereby the deceased pharaoh would mingle with the circumpolar stars.

Mastabas and Pyramids.

From the predynastic mound coveriug the burial, the mastaba evolved as a rectangular superstructure oriented north-south and decorated along its battered, or sloping, sides with recessed paneling. It contained a central two-storied burial chamber surrounded by storerooms, thus imitating a palace or a house. The burial chamber, originally without means of access, was later built deeper underground and was reached by a stairway from the north or east. The storerooms were gradually abandoned, the offerings being replaced by their representations in painting.

At the south end of the east façade there developed an offering recess with a tablet representing the deceased at the funerary repast. Soon the niche came to have a false-door, before which stood an offering table. A chapel enclosed the false-door, and its walls were carved with scenes representing activities of daily life and preparation for the funerary offerings. In the vicinity was a statue chamber containing the statues of the deceased. It was inaccessible, as were the vertical shafts replacing the ramps or ramp-shafts to the deep burial chamber.

Pharaoh, as the son of Re, participated in the daily voyage of this god across the heavens. A pyramid, essentially a solar monument, allowed Pharaoh to ascend to the sun, without precluding the stellar destiny. Royal pyramids were built until the 13th dynasty—and in the 25th dynasty by the Cushite kings.

Rock-cut Tombs. Tombs of the nobility were cut in the cliffs from the 4th dynasty onward and became almost the only ones in the Middle Kingdom, when the nomarchs of middle Egypt preferred to be buried in the cliffs above their cities. The burial chambers were accessible by means of shafts from the forecourt or the tomb chapel.

As the wall area increased, the repertoire of wall scenes developed new topics, such as recreation and entertainment, in addition to the essential ones. In the llth dynasty, scenes of wrestling and the besieging of forts were executed almost exclusively in painting.

In the New Kingdom the rock tomb chapel evolved a cruciform plan and reached deep into the western Theban cliffs. Royal tombs were on a stıaight axis and included an entrance stairway, a corridor intercepted by shafts, and a sarcophagus chamber. While the walls of private tombs were painted with scenes from everyday life, those in royal ones were painted with scenes that were adapted from illuminated religious papyri.

In the Late Period, more impressive than the Saite tombs at Saqqara were the tombs of the Theban grandees, which had huge underground apaıtments imitating multistoried palaces around an open court.

Forts. Military architecture produced small isolated boundary towers in the “predynastic period, forts in middle Egypt later on, and in the 12th dynasty an impressive number of large fortresses along the Nile in Nubia. All the elements characterizing medieval military architecture seem to have been invented by the Egyptians.

Whether enclosed within a rectangular wall when on the river bank or within an irregular triangular one on a rocky island, the fortress complex always featured a main street crossing subsidiary streets at right angles. It had a commandant’s mansion, blocks of square granaries and attached houses of unifonu type, a stairway descending to the river, a drain, and sometimes a temple, a spur wall, and an outer fort.

STATUARY

The earliest three-dimensional representations from Egypt belong to predynastic minor arts: carved handles of ointment spoons, openwork combs, theriomorphic (animal-shaped) vases, and figurines modeled in clay or carved in bone, ivory, or stone. Both small and large human statues conform to the law of frontality, whereby both the head and body face forward.

The fact that most dynastic statuary was set in temples and tombs explains why frontality persisted. It was in keeping with the hallowed sanctity of the place. Kings and high ofReials were represented in a striding posture with the left foot forward and one arm holding a tall staff; or they were shown seated, with one arm on the knee and the other across the breast. Frontality was thus alleviated by unsymmetrical gestures. Women stood with both feet aligned, one arm across the breast. Exceptionally a goddess or a maid carrying a basket was depicted striding. To the ceremonial function of statuary must also be ascribed its forma! style and expression, which did not, however, preclude idealized portraiture. The limbs were held to the body except in wooden statues. These characteristics appear in the archaic ivory figurine of an aging king [British Museum], in the two seated Djeser statues of Pharaoh Khasekhem [Egyptian Museum; here-after, “Cairo”], and in kneeling or seated officials.

Old Kingdom.

A 3d dynasty statue [Cairo] that shows Pharaoh Djeser (Djoser) seated on a cubical throne and clad in jubilee dress conveys an expression of power through the bone structure of the face and through the large hands. The high official Sepa and his wife, Neşet [Louvre], show more of the third dimension than archaie statues, though they are stili stiff in attitude.

Arehaistic peculiarities disappeared in the 4th dynasty with fully three-dimensional, well-pro-portioned and well-modeled sturdy figures with idealized faces. New attitudes (postures) were devised, as in statues of a squatting seribe, group statues of a man with wife and children, and statues of Pharaoh Menkaure accompanied by two goddesses [Cairo] or embraced by his wife [Museum of Fine Arts; hereafter, “Boston”]. Unity in group statues was further achieved by the common back wall, sometimes reaching to the level of the shoulders.

A variety of materials had already been carved in early dynastic times: wood and ivory (1st dynasty), limestone and granite (2d dynasty), and schist (3d dynasty). In the 4th dynasty, veined diorite was used in the larger than life-size well-polished seated Khafre [Cairo], which shows godlike idealized features and a distant gaze. Barely visible from the front is a hawk, symbol of Re, that protects the back of the Pharaoh’s head with outstretched wings. Portraiture is exemplified in the powerful features of an ivory miniature Khufu seated [Cairo], and in the hardly godlike features of Menkaure and the accompanying goddesses.

The court sculptors at Memphis brought the same masterful touch to private commissions intended for the bottom of the tomb shaft, such as the replacement heads (substitutes for complete statues) from the reign of Khufu, showing idealized limestone poıtraits in broad planes [Boston and Cairo]. Other examples are the statues of Rahotep and his wife Nofret [Cairo], which are entirely painted and have inlaid eyes with intense expressions. The inlaying of the eyes—with white stone for the eyeball, obsidian for the pupil, and, for the expression of life, a silver pinhead beneath a rock crystal cover— shows a technical ability that can hardly be matched today. Departure from idealization was achieved in the creases marking the features of the portent architect Hemiwnw [Roemer-Pelizaeus Museum, Hildesheim] and in the unique armless bust of Ankhhaf [Boston],

This level of excellence was maintained in the 5th dynasty with such masterpieces as the high priest Rancfcr [Cairo], the portent administrator Kaaper [Cairo] in wood with inlaid eyes, and the seribe Kay [Louvre] in painted limestone. Wood is1 attested more often than before in elongated figures. Figures in a row, seemingly representing the same personage at various ages, appeared in rock chapels.

With the 6th dynasty the proportions of the figure assumed more slenderness and elegance for both royal and private statuary, as in the statue of Pepy (Pepi) I and his son Merenre [Cairo], with copper sheets hauımered onto a wooden core. Small figures of servants at work aecompanied burials, so that the deceased would have their services in the afterlife.

Middle Kingdom.

In the Middle Kingdom the classie style of architecture was matched in sculpture. Pharaohs were, however, shown with much realism, expressing the worries of kingship, in miniature heads and ıepresentations of Amenemhat (Amenemhet) III as a man-headed lion and of Senusert III as a sphinx.

High officials, who now rose from the plebs, seemingly had no means to commission royal sculptors as did those of the Old Kingdom, mostly close relatives of Pharaoh. Private statuary, worked by provincial artists, was characterized by the long skirt projecting in front. An exception is the granite seated Sennuwy [Boston], vwife of Hepdjefa, showing a subtle expression of nobility and a sweet smile.

New attitudes appeared in wooden statuettes showing a priest holding a libation vessel and a maid carrying a basket on her head and a duck in one hand. Servant statuettes in painted wood, terra cotta, or stone are abundant and inelude new subjects, such as a body of infantry.

New Kingdom and Afterward.

The New Kingdom coutributed surprisingly few attitudes: the block (cube) statue of a squatting man who is wrapped in an ample mantle from which the head of a prineess emerges; the pharaoh profferring a sacred object; and the cow goddess Hathor protecting Pharaoh, who stands before her. New Kingdom style, however, showed a fresh interpretation of earlier attitudes, with slenderer elegant figures and with attire of gradually increasing richness and complexity. Biographical inscriptions were added to the customary offering formula. Pre-Amarna pharaohs of the Thutmosid line were portrayed with an aquiline nose, high cheeks, and pouting lips, while the Amenhoteps had an athletic build and a flat broad face.

During the Amarna interlude the bodily deformities of Akhenaten—represented in an attenıpt at truth and even emphasized as caricature—were adopted as court style, together with supple lines of a new type and bulbous volumes enhanced by long pleated shirts. New attitudes are those of Akhenaten seated, kissing his daughter on his lap, or standing, holding a tray of offerings; and Tutankhanıun on a leopard. In the sculptor Thutmose’s workshop at Amarna were found trial pieces and numerous plaster casts of live and dead models. These works provide invaluable information about the methods used in sculpture.

The post-Amarna period retained some of the stylistic innovations but indulged in elaborate, often extravagant long shirts and hairdos. New attitudes were: Ramses VI striding with his lion and dragging a kneeling captive by the hair; the scribe Ramsesnakht bending over his scroll, his head wrapped within the broad mane of an ape of Thoth that is resting on his shoulders; and a striding man holding the massive emblem post of a Corporation (guild) in front of him.

In the Late Period, the Cushite revival (25th dynasty) produced stone statues with a back pillar and block statues characterized by solidity and occasional realism. Some reaction in portraiture emerged in the Saite impersonal style, in which the subject often wears an artificial smile. Ptolemaic sculpture produced purely Egyptian plump forms and Greek ones, especially in terra cotta and occasionally grotesque. It also achieved a mixed style, as in royal statuary and a group of close-shaven realistic heads.

WALL SCENES

More strictly utilitarian than statuary was the repertoire of wall scenes in private tomb chapels and temples. In temples the scenes also depicted historical narrative.

The composite projection invented in predynastic painting—showing the head in side view and the bust in front view, with the waist and legs in side view—is strictly utilitarian, aiming at the most informative representation. The ground line, forming a base to figures and scenes, and the register system (superimposed horizontal bands) appeared in carved predynastic votive palettes and became a rule. Other graphical conventions were; heroic size for the owner of the monument; the cycle (such as fighting) representing a sequence of consecutive moments of action; and the motif of the triumphant pharaoh holding a captive by the hair. As in the case of statuary, stylization pervaded the human figure and elements of nature such as trees, bushes, and water. Animals, which were shown in side view, were more naturalistic. Perspective was ignored except for sporadic attempts, because it deformed objects. Scale was not uniform. Only occasionally was high relief used instead of raised or sunken relief.

Relief Sculpture.

The predynastic votive palettes, derived from palettes for cosmetics, recorded hunts with some historical implication. Historical narrative culminated in the palette of King Narmer [Cairo], documenting in picture and inscription the final unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. The style is archaic but already conforms to the conventional norms of relief scenes.

Old Kingdom.

In temples the scenes had themes relating to the ritual. In the mortuary complex of the pyramids appeared episodes from the jubilee festival of Pharaoh Djeser (3d dynasty) and offering bearers personifying the estates of Snefru (4th dynasty) or Sahure (5th dynasty), which were essential to the funerary offering ritual. Scenes of historical narrative gradually increased in number. They depicted the arrival of Asiatics on Sahure’s boats; the taking of booty, or even hunting and fishing; the transport of granite columns from Aswan; and a group of faminestricken people. In the sun temple of Neuserre (Niuserre) the creative influences of the sun on plant and animal life were portrayed. Sizable mural compositions often could not be seen as a whole because of the columns of a portico running in front of them, but this in no way restricted their ritual value.

In private mastaba tomb chapels the essential repast scene originating from the archaic tablet appeared in the transom window above the false door. It represented the deceased seated and looking to the right toward a platter of food on a stand, as one or more relatives and attendants stood by. In large scale, this scene appeared also on the wall as part of a group of scenes of daily life. Themes ranged from essential food production (agriculture, animal breeding), to artisans’ activities'(carpentry, metalworking) and recreation (hunting, fishing, games, dance, music). The repertoire developed gradually toward the 5th and 6th dynasties with the increase of available wall area in mastaba tomb chapels and in rock tombs. The style varied from massive figures (4th dynasty) to more elegant ones and more balanced composition (5th dynasty), to crowding (6th dynasty). The technique reached its apex in the tomb chapel of Ti (5th dynasty), increasing in boldness in those of Ptahhetep (Ptahhotep) and Mererwikai (6th dynasty).

Middle Kingdom.

With the rise of local styles after the First Intermediate Period came a new concept of proportions with slender figures and long limbs. Nervous gestures appeared, and coarse-featured faces reflected the presence of new ethnic types in the population. Composition became sparse. Because of the bad quality of the bedrock from which the Middle Kingdom tombs were hewn, wall scenes were mostly painted on a stuccoed mud layer. Some sites like Meir stili had, carved in low relief, scenes of a most vivid realism, such as the cycles of papyrus gathering, boat building, and cattle herding. Relief scenes in temples and tombs were of a richer, livelier composition than in the Old Kingdom.

New Kingdom.

In the New Kingdom, tomb chapels of the grandees at Thebes West emulated the vast relief s of temples. The pharaoh was represented on both sides of the rear wall of the entrance hail, foreshadowing the preeminent role assigned to Akhenaten in the private tombs of Amarna, where the owner appeared only casually. The style evolved from the rich composition and refined facial features of the early 18th dynasty, as in the tomb of Ramose, to small registers teaming with figures with supple lines and angular features, accompanying representations of royalty. The technique was sunken relief.

Though short-lived, the Amarna style influenced wall scenes in the Ramesside tombs at Thebes, introducing a sophisticated refinement verging on mannerism, as in the scene of girls dancing and clapping [tomb of Kheruef].

In the extensive temples of the Empire the majority of the scenes were related to the ritual performed in the various halis. They were done in a traditionalist formal style in raised relief, often of outstanding elegance, as in the temple of Seti I at Abydos. However, the outer walls—and occasionally inner ones, as at Abu Simbel—were reserved for new topics like the battle feats of the pharaohs in their Asian conquests, and their hunts for wild bulls in the marshes [temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu].

These enormous compositions in deeply sunken relief did not depend on the register system. They demonstrated a bold sense of space, arrest, and movement in the chaos of intermingled horses, chariots, and infantry, with the whole scene dominated by the colossal figure of Pharaoh on his chariot. This was the climax of large scale historical narrative. But despite the outstanding success in depicting details and contrasting the obvious power of Pharaoh with the confusion of his enemies, the compositions lacked unity.

Late Period and Asterward.

The realistic trend did not outlive the 20th dynasty, for the high priests of Amun who came to rule at Thebes reinstated traditionalism. Cushite temple scenes such as those at Kawa derive from the mortuary temples of Sahure, Neuserre, and Pepy II. Those at the colonnade of Taharqa (Taharka) in Karnak show ritual scenes in a heavy relief. The relief s from Saite Memphis exhibit subtle drafts-manship and variety in attitudes. The vast wall expanses of Greco-Roman temples were carved with traditional scenes according to a strict rectangular scheme heavily framed within vertical columns of hieroglyphs and horizontal bands. The bold carving showed well-rounded forms. Petosiris’ tomb chapel (325 b. c.) at Hermopolis West is unique in representing traditional funerary subjects in Egyptian style in the pillared hail, while in the later front vestibule an attempted fusion of Greek and Egyptian styles appears in scenes of craftsmen of Greek type» grouping, and gestures with foreshortening.

Painting.

In a predynastic tomb mural from Hieraconpolis almost ali the conventions of Egyptian graphic arts appear. The exception is composition in registers, a later rule that lasted till the end of Egyptian art. Since architectural sculpture was usually painted in polychrome (except for hard stone statues), it was natural that painting flourished stili more when the easier technique of applying pigments to dry stuccoed mud plaster was developed. Throughout the whole history of Egyptian painting, pigments were derived from mineral sources, mostly ochers, and were mixed in a medium of gum or egg white. Brushes were made of the flattened ends of reeds.

Early Dynastic Painting.

Mastaba superstructures of the 1st and 3d dynasties were painted to imitate geometrically patterned mats hanging on a wooden framework. The earliest murals represented items of funerary equipment above a dado along the corridor chapel of the tomb of Hesire, in an accomplished refîned style. The mural of the geese, from the early 4th dynasty tomb of Atet at Meydum, shows ponderous rhythm and a formal, exact interpretation of the characteristics of the species. An isolated experiment with a new technique of inlaying colored pastes with details added in brushwork proved a failure.

Technical ability in a formal design prevailed in mastaba chapels till the end of the Old Kingdom, when the underground burial chamber began to be painted with texts and an upper frieze of funerary equipment. Though most of the process of adding color to low relief was mechanical, certain details appearing only in paint implied original design and brushwork. In the First Intermediate Period secondary colors were introduced. Paintings were done without registers and used elongated figures, nervous gestures, and angular forms.

Middle Kingdom.

The repertoire of Middle Kingdom tomb painting borrowed from that of the late Old Kingdom, with the addition of scenes of wrestling and local war. In the wrestling scenes, as many as eight registers, each about 13V2 inches (30 cm) tal, covered the walls above a dado and beneath a kheker frieze with hundreds of lively paired figures [at Beni Hassan], In most other scenes, however, the composition was formal. Real treasures of detailed brushwork are the interpretations of animal life. Roofs were painted to imitate matwork or elaborate floral patterns. Theban murals of the 12th dynasty used larger figures executed in a more lively style, as in the dancing and hunting scenes in the tomb chapel of Antifoker.

New Kingdom and Late Period.

In the numerous and extensive rock tombs of the New Kingdom in Thebes West, painting developed further at the expense of relief. Scenes in the extensive corridors and halis of royal tombs were enlarged copies of illuminations from funerary papyri, borrowing even their linear style. In the tombs of the Theban grandees, the front hail had scenes of daily life derived from Middle Kingdom murals, whereas the rear hail had scenes of the funeral and pilgrimage to Abydos.

In the Ptolemaic Period, in tombs at Alexandria and Hermopolis West, dadoes imitated marble masonry and incrustation. Above them were murals inspired by classical myths, occasionally portraying the deceased in Greek garb amid Egyptian religious scenes.

MINOR ARTS

From the earliest times, utilitarian objects showed an artistic touch. The Old Kingdom produced spindle whorls inlaid with running quadrupeds, delicate alabaster and red pottery vessels, bracelets, broad collars and diadems, anklets, a golden falcon head with obsidian eyes, and furniture of functional design with lion’s and bull’s legs and with stylized floral elements used in metal lining and inlay work. These objects and decorative elements form an impressive contribution, showing taste and technical ability. Middle Kingdom artisans made pottery, mostly globular vessels and bowls, faience scarabs and hippopotami, globular and theriomorphic vases of alabaster or marble, metal daggers with ivory pommels, mirrors and subtle inlaid jewelry of symbolic design, and garments with beadwork and sewnon gold omaments.

Profuse richness, often of objectionable taste, marked New Kingdom arts. From this period came alabaster lamps, turquoise faience lotiform chalices, polychrome faience architectural inlays and glass vessels, ointment spoons in carved bone and ivory, golden and silver bowls with animal-shaped handles, and boxes, bronze mirrors, and embossed vessels. There were decorative leather tentlinings and eushion covers, and garments had eeramic ornaments sewn on them. Jewelry, with inlays and niello, was often too elaborate. Elegant furniture was sometimes burdened with too much ornament, as in the tomb of Tutankhamen. The same tomb yielded a mummy mask of gold inlaid with enamels and pastes, gold and gift cofBns, richly decorated chests, and numerous other objects—ali now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

In the Late Period, to the traditional crafts accrued millefiori technique for glass and the use of bronze legs with gold niello for furniture. Imports of Greek terra cotta figurines and pottery and Greek influence on jewelry marked Ptolemaic crafts.