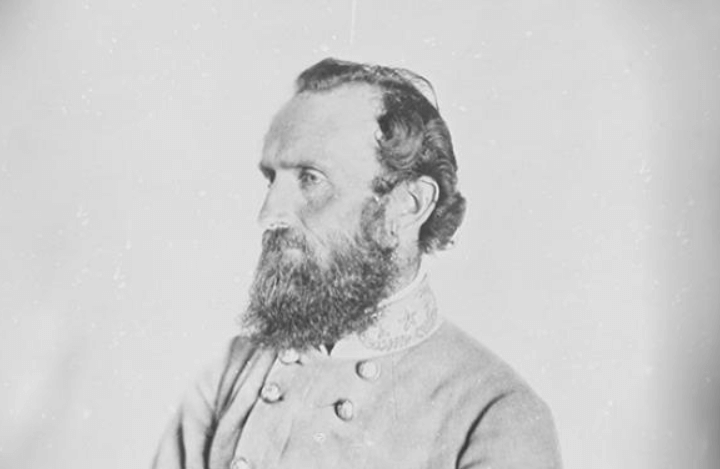

Who was Thomas Jonathan Jackson (Stonewall Jackson)? Information on Thomas Jonathan Jackson biography, life story, military career.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson; (1824-1863), American army officer, who was one of the ablest lieutenants of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in the Civil War and is regarded as one of the outstanding tacticians in military history. He was known as “Stonewall” Jackson.

Jackson was born in Clarksburg, Va. (now in West Virginia), on Jan. 21, 1824. His schooling was sketchy, coming largely from itinerant teachers, and he was scholastically unprepared to win an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, which he sought in 1842. He had worked desperately for the appointment, since it represented his sole means of obtaining a higher education. When the successful candidate resigned, Jackson was made a cadet.

Barely passing his entrance examinations, Jackson entered the academy in June 1842. His classmates included Ambrose Powell Hill and George E. Pickett, who became Confederate generals, and George B. McClellan, commander of the Union Army of the Potomac in the Civil War. Although woefully deficient in training, Jackson fought his way to 17th place in the class standing by the time he was graduated in June 1846. He chose the artillery as his branch of service.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson (Stonewall Jackson)

Early Career:

With K Company, 1st United States Artillery, Jackson went to Mexico as a brevet 2d lieutenant to fight under Gen. Zachary Taylor. Transferred to Gen. Winfield Scott’s army, he participated in the siege of Vera Cruz (March 1847), saw action at Cerro Gordo in April, and was breveted for gallantry in action at Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec. His outstanding conduct earned him the permanent rank of 1st lieutenant and the brevet rank of major by the end of the fighting in Mexico. Assigned to duty with occupation forces in Mexico City, Jackson spent several happy months there and became something of a social lion. He studied Spanish, flirted with romance, and urged by Capt. Francis Taylor, his commanding officer, he undertook a personal study of religion, beginning with Roman Catholicism. Soon he had evolved a private code of morals which served until his affiliation with the Presbyterian Church on Nov. 22, 1851.

In July 1848, Jackson returned to the United States and served at various New York and Pennsylvania forts until October 1850, when he and his company were sent to the Seminole Indian theater in Florida. At Fort Meade, Fla., he had an unhappy altercation with the post commander, Maj. William Henry French, and the episode ended with Jackson’s departure from the service on May 21, 1851, with nine months’ terminal leave. He accepted a professorship of natural and experimental philosophy and artillery tactics at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) at Lexington, Va. His former Mexican war comrade and future brother-in-law, Maj. Daniel Harvey Hill, had nominated him for the position. Jackson taught at VMI from August 1851 until April 1861. Never a popular teacher, he became the butt of many cadet pranks, the object of much derisive doggerel verse, and the target of the Society of the Alumni. A few cadets saw beneath his cloak of shyness, and those came to appreciate him as a “grand, gloomy and peculiarly good man.”

The Lexington decade brought great changes in Jackson’s personal life. Here he found the religion he had long sought and devoted himself to it with characteristic wholeheartedness. Here, too, he found a real and happy home for the first time. On Aug. 4, 1853, he was married to Elinor Junkin, daughter of the Reverend George Junkin, president of Washington College in Lexington. Under her gentle influence he began to doff his relentless punctilio, to curb his terrible shyness, and to be himself—at least among his family and close friends. A tragic end to this period of home life came on Oct. 22, 1854, when Mrs. Jackson died in childbirth. After months of despondency, Jackson remarried. His new bride, Mary Anna Morrison of North Carolina, was also the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, and a sister of Mrs. Daniel Harvey Hill. After their marriage on July 16, 1857, the Jacksons bought a house and finally moved in during the winter of 1858. Again Jackson entered into the spirit of contented domestic life.

Outbreak of Civil War:

The first interruption of this new-found happiness came with the John Brown crisis in October 1859. Jackson took part of the VMI cadet corps to witness Brown’s hanging in December, and afterward bent his efforts toward preparing for whatever emergency the Union might face. A Democrat and small slaveholder, Jackson voted for John C. Breckinridge in 1860 and remained a Union man until Virginia seceded on April 17, 1861. On April 21, Jackson led the VMI cadets to Richmond, and on the 27th, although unknown in Virginia political circles, he received a commission as colonel in the Virginia state forces, with orders to organize the defense of the strategic town of Harpers Ferry. Jackson, taking charge of a disorganized group of militiamen, soon had a well-trained brigade under his command, and posted guns to command the heights overlooking the town, the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, and the important Baltimore and Ohio railroad bridge. On May 24 he turned the post over to Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and assumed command of a brigade in Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah. With this brigade he engaged Gen. Robert Patterson’s Union forces at Falling Waters, Va., on July 2, 1861, and in his first battle command of the war gained a tactical success. Shortly after this engagement he was commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate Army, effective June 17, 1861.

First Bull Run:

Jackson’s brigade, with the rest of Johnston’s army, went to aid Gen. Pierre G. T. Beauregard at Manassas Junction on July 18, and on July 21 took a decisive part in the Battle of Bull Run (Manassas). Posting his brigade on the strategic Henry House Hill toward the Confederate left, Jackson steadied the Southern front against the flank attack by Gen. Irvin McDowell’s Union troops. Jackson’s men, standing firm on the hill, caught the attention of Gen. Bernard E. Bee as he tried to rally his shaken troops; he pointed to Jackson’s line and shouted an immortal battlecry: “There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer.” The sobriquet “Stonewall” stuck with Jackson from that day of victory at the Battle of the First Bull Run.

Romney Expedition:

Praise for Jackson came from all parts of the Confederacy, and on Oct. 7, 1861, he was commissioned a major general. In November he went to the Shenandoah Valley to command the newly created Valley District, which embraced all the territory between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny mountains, from Staunton to Harpers Ferry. Finding only some 1,600 men available in the valley, Jackson called out the militia of the district and obtained the assignment of his own original “Stonewall Brigade.” With additional reinforcements bringing his total strength to about 8,500 men, he began a winter campaign in January 1862 to reoccupy Romney, Va., then held by Union forces. After a march tragically like Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow, Jackson occupied the town on January 14, left a garrison, detached troops to neighboring settlements, and took his own brigade back to district headquarters at Winchester, Va. The Romney expedition earned Jackson the hatred of some subordinates, and complaints to Richmond prompted Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin to order the reconcentration of Jackson’s entire command at Winchester. Faced with civilian interference in his military assignments, Jackson submitted his resignation, but the wise counsel of General Johnston, the urgings of clerical friends, and the protest of Virginia’s governor, John Letcher, changed Jackson’s mind.

Shenandoah Valley Campaign:

Ordered to protect Johnston’s left flank against a thrust by the Union general, Nathaniel P. Banks, Jackson reorganized his army. When he heard that Banks had detached men to the eastern theater, Jackson determined to attack him in the hope of recalling the detached troops. With a reduced force he struck Banks’ rear guard under Gen. James Shields at Kernstown on March 23, 1862, sustained a tactical defeat, but gained a strategic victory which brought Banks’ men back to the valley. Gen. Robert E. Lee, who had direction of military operations outside of the Richmond sector, advised further pressure against Banks, and Jackson, reinforced by the division of Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell in late April, began his world-famous Shenandoah Valley campaign. Deceptively moving toward Richmond, he marched his own division rapidly out of the valley, reversed direction, and went to the support of Gen. Edward Johnson west of Staunton. With 10,000 men Jackson attacked Gen. Robert H. Milroy’s forces near the village of McDowell, Va., on May 8, defeating and driving them toward Gen. John C. Fremont’s Union army near Franklin, Va. With his left flank secure, Jackson returned to the Shenandoah Valley and, joined by Ewell’s division, struck at Banks. With about 16,000 men and 48 guns, he obliterated Banks’ outpost at Front Royal on May 23, thus forcing him to retreat from Strasburg toward Winchester. Washington was convinced that a major threat to the North had developed in the valley. Hearing of Banks’ headlong flight, President Abraham Lincoln withdrew troops from General McDowell’s army near Fredericksburg and consequently stalled General McClellan’s operations against Richmond. Jackson had gained his primary objective; he had protected the Confederate capital for a time.

Jackson defeated Banks at Winchester on May 25, 1862, and drove him toward Williamsport on the Potomac. Advised that Lincoln planned to trap him, Jackson retreated swiftly—so swiftly that his men earned the name “foot cavalry”— and eluded two Federal armies. At Cross Keys and Port Republic, in the southern end of the valley, Jackson turned on the armies of Fremont and Shields, defeating them in succession on June 8 and 9. The lightning valley campaign had paralyzed no less than 60,000 Federal soldiers (at least 40,000 of whom should have been aiding McClellan at Richmond) and frightened Washington. It buoyed up sagging Southern spirits and gave the Confederacy a new hero.

Defense of Richmond:

With Federal thrusts blunted in the valley and with many bluecoats out of position beyond the Blue Ridge, General Lee called Jackson to Richmond to assist in defeating McClellan. Lee planned a wheeling turn around McClellan’s right flank north of the Chickahominy River—a turning movement which would force the Federals out of their works and drive them into the James River. The attack was to begin on June 26, 1862, but Jackson proved unaccountably late. Lee’s battle began badly, with a bloody attack on Union positions which Jackson should have flanked. All during the 26th, Jackson took no part in the action; but on the 27th, reinforced by D. H. Hill’s division, he reached McClellan’s flank and rear and sought to squeeze the enemy’s right between his troops and Lee’s units at Gaines’ Mill. After costly fighting the Federals escaped across the Chickahominy. Lee’s army rested a day while he sought information on enemy intentions. On June 29, Jackson was delayed most of the day at the Grapevine Bridge by orders from army headquarters, and on the 30th he fell into a strange lethargy. He made no serious effort to cross White Oak Swamp Bridge, despite a heavy battle raging at nearby Frayser’s Farm. For this failure he has been severely criticized by military analysts, and many reasons for it have been offered. Some ascribe it to unfamiliarity with the ground, to poor staff work, and to lack of experience in commanding a large force. Perhaps a better reason is physical exhaustion; Jackson had been in the saddle for several days prior to the White Oak action, and he was worn down by exertion, by the unaccustomed heat, and the dank swampland. All these factors combined to put him in a state of somnolence. He regained his aggressiveness on July 1, fighting hard at Malvern Hill.

Second Bull Run (Manassas):

With McClellan driven to the protection of his gunboats, Jackson proposed an invasion of the North. Although Confederate resources did not permit a sustained offensive, Lee apparently concluded that Jackson did better in independent commands which permitted wide discretion, and began a model partnership with him, detaching Jackson to deal with a new Federal invasion army under Gen. John Pope. Jackson met Pope’s advance under Banks at Cedar Mountain on Aug. 9, 1862, sustained an initial reverse, and then routed the enemy. Lee then determined to send part of the Army of Northern Virginia behind Pope and cut him off from Washington. Jackson drew the flanking assignment, took his wing of the army around Pope’s right, and hit the Federal supply depot at Manassas Junction. After purloining and destroying an incredible amount of supplies, Jackson entrenched a strong position near the old Bull Run battlefield and beat off a heavy attack by Pope on August 29. When Pope renewed the advance on the 30th, he went against both Jackson’s and James Longstreet’s wings, but did not know it until he had been beaten in the Battle of Second Bull Run (Manassas). One of Jackson’s men ventured that the battle had been won by hard fighting, but Jackson, in a typical reply, answered: “No, no, we have won it by the blessing of Almighty God.” Defeats might be the result of human error, but victories were gifts from Providence.

Harpers Ferry and Antietam (Sharpsburg):

Lee now decided to carry the war to the North, and in order to clear his line of communications with Richmond through the Shenandoah Valley, he again trusted to Jackson a vital independent assignment: Jackson’s wing would eliminate the 11,000-man Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry and rejoin the main army near Hagerstown, Md., in mid-September. With cold efficiency Jackson plotted the reduction of the enemy garrison by artillery, and on September 15, Harpers Ferry was surrendered. The action had been one to please a professor of artillery tactics. Informed of the rapid advance of a rejuvenated Federal army, again under McClellan, Jackson left A. P. Hill’s division to arrange the surrender and marched rapidly with the remainder of the wing to Sharpsburg, Md., where Lee had retired to reconcéntrate. On September 17, Jackson’s men resolutely stood like a stone wall on the left of Lee’s line at the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg), and the timely arrival of A. P. Hill saved the day for the Confederates. Lee retired across the Potomac » during the night of September 18-19. Jackson’s quick decision to attack a probing Union force at Shepherdstown, early in the morning of the 19th, probably saved the army; it certainly saved the reserve artillery.

After the Maryland campaign Lee reorganized the army into two corps. On Oct. 10, 1862, Jackson was commissioned a lieutenant general and assigned command of the Second Corps; Longstreet would command the first. Lee took Long-street’s men east to watch Federal moves, leaving Jackson in the Shenandoah. On November 22 (the day before his daughter Julia Laura was born), Jackson moved his corps toward Fredericksburg, where he took position on the right of Lee’s line. Here he held against determined Federal assaults during the Battle of Fredericksburg (Dec. 13, 1862).

The army went into winter quarters near Fredericksburg to await the spring campaign. These quiet months Jackson devoted to improving himself as an army administrator, and in keeping with his motto, “You may be whatever you resolve to be,” he succeeded.

Chancellorsville:

Federal Gen. Joseph Hooker began the spring campaign on April 29, 1863, by marching up the Rappahannock in an attempt to turn Lee’s left. Jackson, sent to meet Hooker, hit the enemy advance in the Wilderness near Chancellorsville on May 1, 1863. By nightfall Jackson and Lee, working in close harmony, decided that Hooker must be flanked, and Lee gave Jackson his greatest orders: if a feasible route could be found, he would command the flank march. By dawn of May 2, scouts reported a road which would lead Jackson behind the bluecoats. He prepared to march with some 28,000 men, leaving Lee about 15,000 to face Hooker’s entrenched force of over 100,000. At 5:15 p. m. on May 2, after a 15-mile march—one of the greatest marches of history—Jackson attacked Hooker’s right flank element, the 11th United States Army Corps, and literally blew it out of the war. He intended to get between Hooker and the fords of the Rappahannock and to squeeze the enemy between his own and Lee’s men. After the first impetus of the attack waned, Jackson halted his men to regroup and trotted ahead of his line to reconnoiter.

When he rode back on his sorrel toward his own men, he and his staff were mistaken for Federals and fired on; Jackson’s left arm was shattered, and he was hit in the right hand. His arm was amputated, his other wounds were dressed, and he was moved to Guiney’s Station, a safe distance from the front. Although indications were that he would recover, pneumonia set in on May 7; he grew rapidly worse, sinking into a limbo of lucidity and delirium. Several times Jackson roused himself to see his wife. He clung firm to his faith, and occasionally he thought of the army. In the afternoon of May 10, 1863, a Sunday—he had always wanted to die on Sunday—he rallied to speak his stirring last words: “Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.”

The Confederacy grieved for its fallen captain; even the Federals mourned the loss of a great American. Richmond held one of the last state funerals, and Stonewall was laid to rest in Lexington. Many speculated then, and have since, that with his death the South lost its chance to win the war. Certain it is that the impetus of victory died with him.