What is the detailed life story, biography of Theodore Roosevelt? Information on Theodore Roosevelt youth, career, presidency and death.

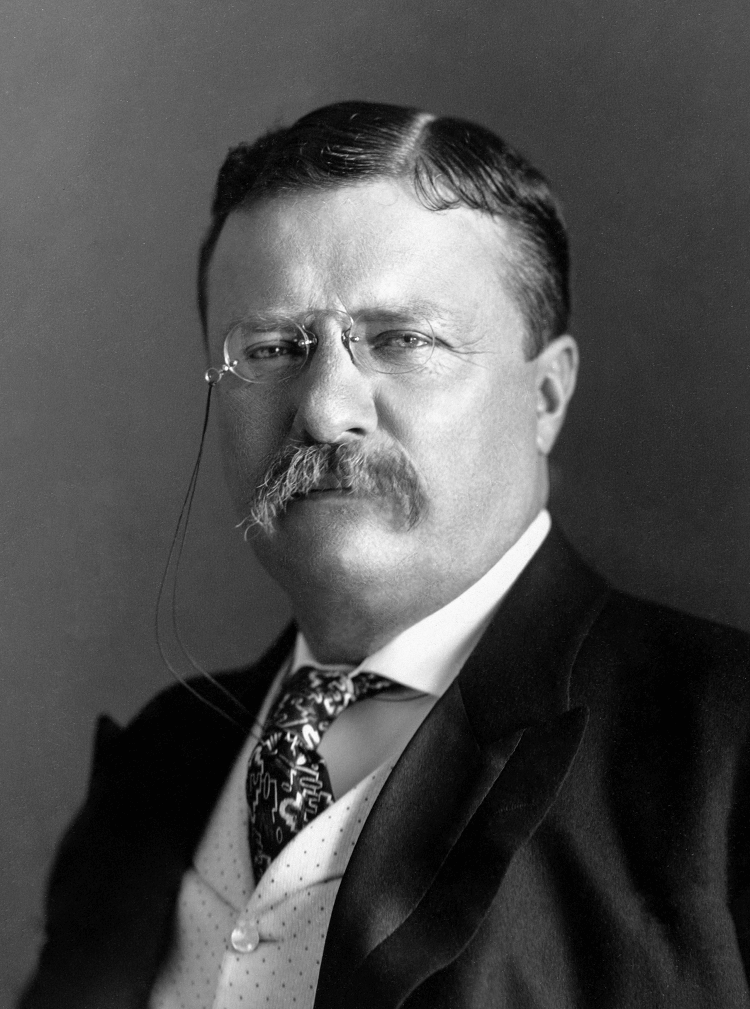

Theodore Roosevelt; (1858-1919), 26th president of the United States. A dynamic leader and a fervent nationalist, Roosevelt was one of the most popular, controversial, and important presidents. He greatly expanded presidential power while making the United States the virtual guardian of the Western Hemisphere and a major force in European and Far Eastern affairs. He was also the first president-reformer of the modern era—the first who both understood and reacted constructively to the technologictel revolution and the rise of a nationwide system of commerce and industry. He increased regulation of business, encouraged the growth of labor unions, and stimulated the rise of the welfare state. He also dramatized the need to conserve natural resources, and his policies advanced the cause of conservation.

As the scion of a mercantile family long prominent in New York City’s affairs, Roosevelt was imbued with a sense of noblesse oblige and civic responsibility and with the conviction that morality was the measure of manliness. Neither his later realization of the imperfectibility of man and his institutions nor his acceptance of politics as the art of the possible ever changed the ultimate ideal. Unquestionably, he was the greatest preacher ever to occupy the White House. Yet his egotism was strident, he was often self-righteous, and he sometimes acted ruthlessly. Despite extraordinary services to world peace while president, moreover, he came close to being a lover of war.

Withal, Roosevelt had great personal charm, remarkable intellectual humility, and a genuine commitment to peace in the abstract. His curiosity was the most wide ranging since Jefferson, and his intellectual achievements were truly impressive. His four-volume historical work The Winning of the West (1889-1896) was justly acclaimed by professionals. Some of the passages in his writings on nature are still unsurpassed. And his knowledge of literature was extraordinary. “He was our kind,” said Robert Frost. “He quoted poetry to me. He knew poetry.”

EARLY LIFE

Theodore Roosevelt, the second of four children, was born in New York City on Oct. 27, 1858, of Dutch, English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish, French, and German stock. The Dutch strain came from his father, Theodore, whom he adored and feared. “I realize more and more every day,” he wrote as a young man, “that I am as much inferior to Father morally and mentally as physically.” His mother, Martha Bulloch of Georgia, was a flighty, ineffectual woman. Partly because of his poor health—he suffered from asthma and defective vision—Theodore was educated by tutors until he entered Harvard College. To gain strength, he taught himself to ride, box, and shoot, and he early developed interests in natural history and military affairs. At Harvard, he began work on a book of scholarly merit, The Naval War of 1812, which was published two years after he received his B. A. degree in 1880. At Harvard he also won membership in Phi Beta Kappa.

Source : wikipedia.org

Meanwhile, on Oct. 27, 1880, Roosevelt married Alice Hathaway Lee. This supremely happy union ended with Alice’s death on Feb. 14, 1884, following the birth of a daughter, Alice. Roosevelt’s mother died the same day. The baby Alice survived; was subsequently married in a lavish White House ceremony to Nicholas Longworth, a future Speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives; and became an outspoken observer of political and social activities in Washington, D. C.

When tragedy struck, Roosevelt was already serving his third term in the New York state Assembly. First elected at the age of 23, he rose rapidly in influence. As the leader of a minority of reform-minded Republicans, he pushed through a number of “good government” bills. He also began to break with laissez-faire by fighting successfully for regulation of tenement workshops. In 1884, Roosevelt opposed the presidential aspirations of former Secretary of State James G. Blaine, whose reputation for integrity was not the highest, but he refused to bolt the Republican ticket after Blaine was nominated.

From 1884 to 1886, Roosevelt sought to alleviate his loneliness by writing history and by operating a cattle ranch in the Dakota Territory, where he earned the respect and affection of the cowhands and ranchers. He returned east in the fall of 1886 to run for mayor of New York against Congressman Abram S. Hewitt and the economist Henry George. Hewitt, a Democrat, won decisively, Roosevelt finishing a poor third.

Roosevelt then married his childhood sweetheart, Edith Kermit Carow, in London. An intelligent, sensitive, and cultivated woman, Edith was essentially a private person. Resignedly, she accepted many of her husband’s most disruptive decisions, such as his break with the Republican party in 1912, in the realization that they “were best for him.” She bore him four sons—Theodore, Jr.; Kermit; Archibald; and Quentin—and a daughter, Ethel (Mrs. Richard Derby). The energetic young Roosevelts would become the liveliest group of children to live in the White House.

For two and one-half years after his second marriage Roosevelt lived as a sportsman and gentleman-scholar in Sagamore Hill, a spacious gabled house at Oyster Bay, on Long Island. He published biographies of Couverneur Morris and Thomas Hart Benton and works on the American West, some based on his personal experiences. Captivated by visions of military glory, he hoped at times for “a bit of a spar” with Mexico, Cuba, ( or Germany. Finally, in 1889, an appointment to the U. S. Civil Service Commission gave him the constructive outlet he needed.

Public Servant.

As head of the commission for much of his six years of service, Roosevelt was guided by the belief that the spoils system was “a fruitful source of corruption” that kept “decent men” out of politics. Civil Service examinations were revised, fraud was pursued relentlessly, and the number of positions open to competitive examinations was doubled. In addition, women were placed on the same competitive plane as men in many positions. The annual reports, writes one eminent historian, “revealed the presence of a new vigor and administrative power, and of a mind appreciative at once of ideal ends and practicable possibilities.”

Roosevelt left Washington in 1895 to serve two turbulent years as president of the Police Commission of the City of New York. He was opposed not only by Tammany Hall—the Democratic organization—and the vice interests, but also by powerful elements of his own party. In particular, the Republican party’s large German-American constituency resented his enforcement, in order to eliminate payoffs to the police, of a law closing saloons and beer gardens on Sundays.

Although corruption returned after Roosevelt left office, many of his administrative and other reforms proved permanent. And he had gained insights into unpleasant aspects of urban slum life.

War With Spain.

President William McKinley named Roosevelt assistant secretary of the navy in 1897. In this office, Roosevelt worked behind the scenes for war against Spain, which was struggling to suppress an independence movement in Cuba. He was animated both by strategic considerations—he wished to see European influence eliminated from the Caribbean islands— and by the conviction that “superior” nations had the right and duty to dominate “inferior” ones in the interest of civilization. He was also moved by his idealization of war. Thus he declared in an address: “No triumph of peace is quite so great as the supreme triumph of war.”

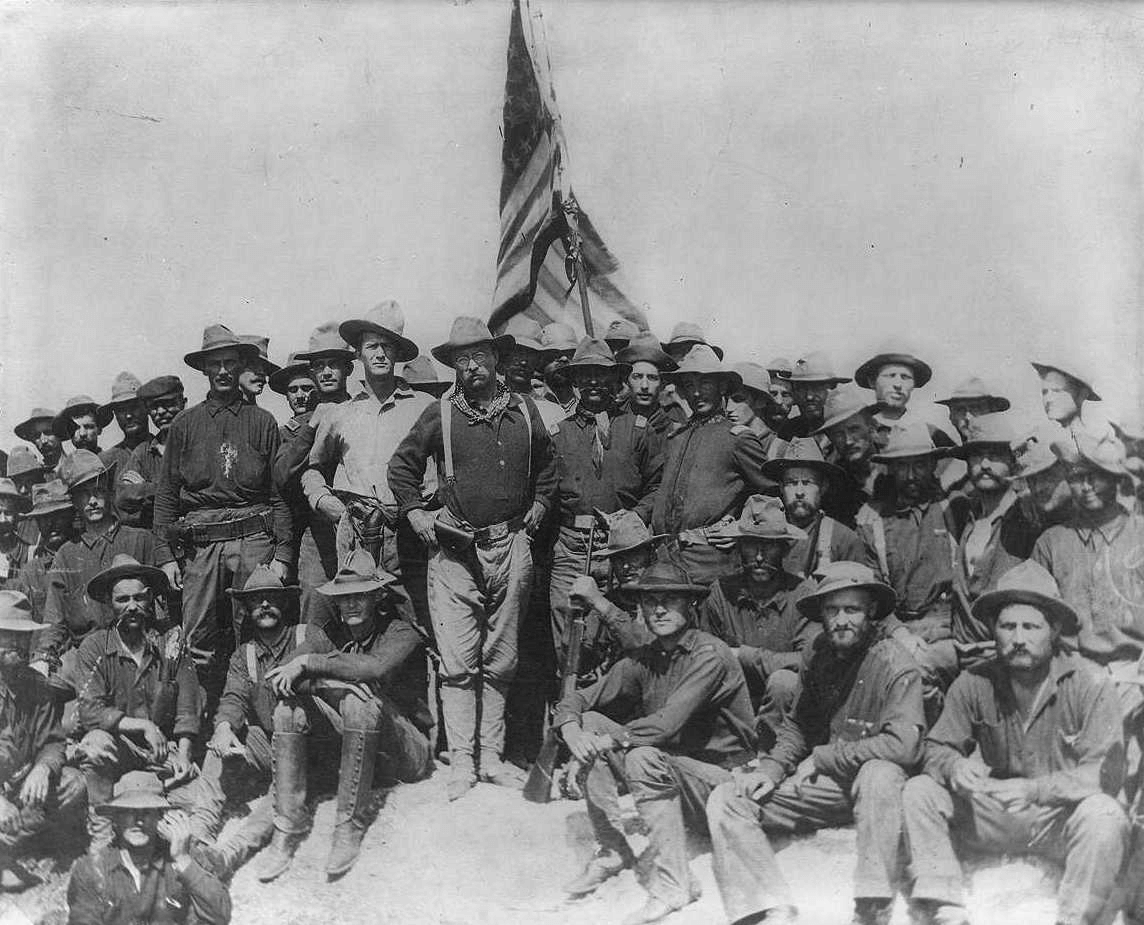

On the outbreak of hostilities in 1898, Roosevelt resigned his position as assistant secretary to accept a lieutenant colonelcy in the 1st U. S. Volunteer Cavalry (the “Rough Riders”). Promoted to colonel in Puerto Rico, he led the Rough Riders in a heroic charge up Kettle Hill in the battle for San Juan. This feat established his reputation throughout the United States.

Governor and Vice President.

Roosevelt returned to New York in the summer of 1898 to run for governor. As expected, he ran far ahead of his ticket that fall, though he won by fewer than 20,000 votes. Armed with his own righteous enthusiasm and supported by a public opinion that he both formed and reflected, Roosevelt became the best governor of New York to that time. Even the fiercely Democratic New York World conceded that “the controlling purpose and general course of his administration have been high and good.” He imbued many officials with a new sense of public trust, and he instilled in others the fear of dismissal. Roosevelt antagonized corporations and the Republican political machine headed by Sen. Thomas Collier Piatt by driving through a tax on corporate franchises, and he supported pro-labor measures even as he called out the National Guard to suppress a strike. He also upgraded teachers’ salaries, spurred passage of a bill to outlaw racial discrimination in public schools, and made a stab at arresting the blight of the slums. Finally, he took important steps to preserve the wildlife, forests, and natural beauty of his state.

Source : wikipedia.org

The business community’s resentment of Roosevelt’s tax, regulatory, and other programs prompted “Boss” Piatt to try to ease him out of the state. Piatt encouraged Roosevelt to seek the office of vice president on the ticket with President’ McKinley in 1900. The office had been vacant since the death of Vice President Garret Hobart in 1899. McKinley remained publicly neutral on the vice-presidential nomination, and Roosevelt was not enthusiastic about running because he liked being governor and because he viewed the position as unchallenging. Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Mass.), his close friend, urged him to take the vice presidency as a possible stepping-stone to the presidency. Conversely, Sen. Marcus A. Hanna (R-Ohio), McKinley’s principal political adviser, regarded Roosevelt as a “damned cowboy” and opposed his nomination. But Roosevelt was popular throughout the nation and he was nominated easily.

Roosevelt campaigned strenuously and was swept into the vice presidency by the McKinley landslide. Six months into his second term McKinley was assassinated at Buffalo, N. Y., and on Sept. 14, 1901, Roosevelt took the oath of office at Buffalo and became president. At 42, he was the youngest man to hold that office.

PRESIDENT: FIRST TERM

After being sworn in, Roosevelt pledged “to continue, absolutely unbroken” the policies of McKinley. But he also observed, “I am president,” and he moved beyond his conservative predecessor both in style and substance. A number of McKinley administration officials continued to serve under Roosevelt, notably John Hay as secretary of state, Elihu Root as secretary of war, and Philander C. Knox as attorney general.

Domestic Affairs.

As president, Roosevelt conceived of himself as the representative of all the people—farmers, laborers, and white collar workers no less than businessmen—and for seven and one-half years he strove to balance their interests. He thrust hardest, however, toward bringing big business under stronger regulation. Unlike many radical progressives, he perceived both the economies that could be achieved in large-scale production and the need for capital formation. Therefore, he sought to regulate, rather than dissolve, most trusts.

Yet Roosevelt also believed that some trusts should be destroyed. He further wanted to force Congress to support his regulatory program by threatening independent action. Accordingly, he soon instituted antitrust proceedings against the Northern Securities Company. This mammoth railroad combine was the creation of the most powerful finance capitalists in the nation—J. P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, Edward H. Harriman, and James J. Hill—and Roosevelt’s bold attack on it stunned businessmen. As the Detroit Free Press observed, “Wall Street is paralyzed at the thought that a President. . . would sink so low as to try to enforce the law.” In 1904 the U. S. Supreme Court upheld the government’s dissolution of Northern Securities.

Mr. Dooley, the creation of humorist Finley Peter Dunne, took note of Roosevelt’s ambivalence on the trusts:

“Th’ trusts,’ says he, ‘are heejoous monsthers built up be th’ inlightened intherprise iv th’ men that have done so much to advance progress in our beloved counthry,’ he says. ‘On wan hand I wud stamp thim undher fut; on th’ other hand not so fast.’ “

Although 25 indictments and 18 proceedings in equity followed, most of Roosevelt’s energy went into regulation. In 1903 he signed the Elkins anti-rebate railroad bill, which ended the practice by railroads of showing favoritism through the granting of rebates on freight rates. Roosevelt virtually coerced Congress into creating a’ Bureau of Corporations within the new Department of Commerce and Labor. The bureau was empowered to investigate and report on most corporations. Meanwhile, in 1902, he forced the anthracite coal industry to settle a prolonged strike by agreeing to accept the recommendations of an independent arbitration committee appointed by himself. This ostensibly even-handed action was actually the first important pro-labor intervention by any U. S. president.

Foreign Affairs.

Despite Boosevelt’s earlier glorification of war, his conduct of foreign policy while president was prudent and realistic. Characteristically, he broke precedents, acted independently of Congress, and held himself ready to invoke force in pursuit of the national interest. But his conception of the national interest became progressively more enlightened. He abandoned the notion that a far-flung empire was the hallmark of greatness at the same time that he made the United States a world naval power. He admitted Japan to that circle of “superior” nations sanctioned to dominate the world. He also supported the international court of arbitration established at The Hague, and he had the United States play a perhaps crucial role at the Algeciras Conference (1906), at which France and Spain were granted greater influence in Moroccan affairs at Germany’s expense.

Roosevelt’s most controversial action involved Panama. He had long recognized an Isthmian canal’s importance to American commerce, and early in 1903 he arranged to buy out a French company’s rights to construct a canal through Panama, then a part of Colombia. Outraged when the Colombian senate rejected his terms, he tacitly encouraged a revolution in Panama. (“I took Panama,” he later declared.) Subsequently, the new Republic of Panama granted the United States full sovereignty over a strip lu miles (16 km) wide through which the Panama Canal was constructed. Roosevelt took a direct interest in the building of the canal, though it was not completed during his presidency.

Roosevelt had no desire to establish a formal empire in the Caribbean, and in 1902 he withdrew American troops from Cuba. He feared, however, that European powers would use nonpayment of debts as an excuse for intervention in Latin America, and in 1903 he warned off the Germans from Venezuela. The next year he asserted that in the event of “chronic wrongdoing” or “impotence” on the part of Latin American states, the United States alone assumed the right to intervene and to ensure that the Latin American states met their financial responsibilities to other nations. Acting on this principle—the so-called Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine—he reluctantly took over the customs houses in the corrupt and bankrupt Dominican Republic. He had, he privately explained, about the same desire to annex that country “as a gorged boa constrictor might have to swallow a porcupine wrong-end-to.”

Election of 1904.

Roosevelt’s election in 1904 to a full term was a foregone conclusion. Senator Hanna, a potential rival for the nomination, died before the convention, and Republican conservatives had no one else to turn to. Roosevelt’s Democratic opponent, Judge Alton B. Parker of New York, was a colorless conservative. Even the spokesmen of high finance supported Roosevelt in the persuasion that “the impulsive candidate of the party of conservatism” was preferable to “the conservative candidate of the party which the business interests regard as permanently and dangerously impulsive.” Roosevelt and his running mate, Sen. Charles W. Fairbanks (Ind.), swept the electoral college, 336 to 140, and won the greatest popular victory to that time, polling 7,628,831 votes to 5,084,533 for the Democrats. In an election-night statement that weakened his later effectiveness, Roosevelt renounced aspirations for another nomination in 1908.

Source : wikipedia.org

PRESIDENT, SECOND TERM

Despite the magnitude of Roosevelt’s victory, Republican Old Guardsmen in the Senate continued to regard him as a maverick. Repeatedly, they forced him to compromise or accept defeat on his legislative program. As the president complained, “Congress does from a third to a half of what I think is the minimum that it ought to do.” Emboldened, nevertheless, by his popular mandate, Roosevelt invoked the moral and political authority of his office to secure an impressive body of legislation, which he collectively called the Square Deal.

Changes in the cabinet included the appointment of Root to succeed Hay as secretary of state on the latter’s death in 1905, and the appointment of William Howard Taft to succeed Root as secretary of war.

The Square Deal.

The first major achievement of Roosevelt’s second term was the Hepburn Act of 1906, which gave the Interstate Commerce Commission power to fix railroad rates and to prohibit discrimination among shippers. That same year Roosevelt won approval of the Pure Food and Drug bill and a meat-packing inspection measure. He also prevailed on Congress to enact an employer’s liability law.

The reform movement was fueled by exposes in periodicals. Roosevelt denounced the most extreme crusaders as “muckrakers” in 1906. He did so because he felt that they were inculcating an attitude of negativism in the public. He further desired to appease conservatives in order to marshal their support of his own and, ironically, the muckrakers’ reforms.

As Roosevelt’s tenure lengthened, his comprehension of social and economic problems continued to sharpen. His goal was a more orderly, more efficient, and more just society, and he proposed to attain it by transforming government into a responsive, science-oriented meritocracy. This objective and his militant calls for action and unabashed use of his executive powers combined to alienate Congress further. During the last two years of Roosdvelt’s presidency Republican leaders defied him almost continuously. Finally, on Jan. 31, 1908, Roosevelt lashed back in one of the most bitter and radical presidential messages on record. He charged that the representatives of “predatory wealth” were thwarting his program. He called for stringent regulation of securities. And he censured the judiciary for failing “to stop the abuses of the criminal rich.” Additional special messages amplified these and other matters, including the need for income and inheritance taxes and guarantees to workingmen of “a larger share of the wealth.” Notwithstanding the refusal of Congress to act, Roosevelt’s rhetoric did much to prepare the way for reform under his successors.

Conservation of Natural Resources.

By then the president was also engaged in an acrimonious struggle for rational control and development of natural resources. In no other movement did he blend science and morality quite so effectively, and in only one other—foreign policy—did he submerge partisan politics so completely. For more than seven years, often against the opposition of both parties, he pressed Congress and the states to put the future public interest above the current private interest.

In 1902, Roosevelt gave his support to the Democratic-sponsored Newlands Act. Under its authority 30 irrigation projects, including Roosevelt Dam in Arizona, were begun or completed during his presidency. In the meantime he vetoed a bill to authorize private development of the Muscle Shoals Area of the Tennessee River, later the heart of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Then, in 1905, Roosevelt reorganized the Forest Service and made Gilford Pinchot its chief. Encouraged by Roosevelt, Pinchot staffed the agency with trained foresters, and, for the first time, development of waterpower sites by private utilities was subjected to enlightened safeguards. Three times as much land (125 million acres, or 50 million hectares) as Roosevelt’s three immediate predecessors had assigned to national forests was put into the reserves. A vast acreage of coal and mineral deposits was subjected to federal control. In another significant development, many large lumber corporations were persuaded to adopt selective cutting techniques.

Undaunted by charges of “executive usurpation,” Roosevelt also doubled the number of national parks, his five additions including Mesa Verde and Crater Lake; created 16 national monuments such as California’s Muir Woods; and established 51 wildlife refuges. “Is there any law that will prevent me from declaring Pelican Island a Federal Bird Reservation?” the President asked. “Very well, then I so declare it.” As Roosevelt’s long-term adversary. Sen. Robert M. LaFollette (R-Wis.) later wrote, Roosevelt’s “greatest work was inspiring and actually beginning a world movement for . . . saving for the human race the things on which alone a peaceful, progressive, and happy life can be founded.”

Race Relations.

Roosevelt believed that racial discrimination was morally wrong and that a fragmented society could not flourish indefinitely. During his first term he appointed a number of highly qualified blacks to office in the South at the instance of the black educator Booker T. Washington, and he tried to create a biracial Republican organization in the South led by patrician whites. He also denounced lynching and struck against peonage through the courts. But the results were counterproductive. Southern political leaders and editors reduced enlightened white Southerners to silence by inveighing against “Roosevelt Republicanism,” while the virtual completion of disfranchisement of Southern blacks by state action destroyed all possibility of creating a viable biracial GOP in the South.

Further regression in racial matters marked Roosevelt’s second term. He let several state organizations become “lily white,” made no statement on the Atlanta race riot of 1906, and discharged a large group of black soldiers for “conspiring” to protect fellow blacks falsely charged with murder in Brownsville, Texas. Reduced to inertia by his perception that fundamentally “the North and the South act in just the same way toward the Negro,” Roosevelt failed signally to give the civil rights movement the kind of moral and educational leadership that he gave other causes then unattainable.

The Far East.

Roosevelt had come into office enamored of the potential commercial and strategic fruits of America’s venture into the Pacific. “I fail to understand how any man . . . can be anything but an expansionist,” he told an export-conscious audience in San Francisco in 1903. Two years later he resorted to gunboat diplomacy to force the Chinese government to stop a boycott of American goods inspired by the exclusion of Chinese immigrants by the United States. Meanwhile he gradually concluded that the Philippines, which he privately termed “our heel of Achilles,” were at the mercy of Japan.

Roosevelt’s solution was to cultivate friendly relations with Japan and foster a balance of power between Japan and Russia. In 1905 the Japanese disavowed designs on the Philippines, and Roosevelt secretly recognized Japan’s suze-raignty in Korea. That same year, in an action that earned Roosevelt the Nobel Peace Prize, he mediated the end of the Russo-Japanese War. Then, in 1907, he forced the San Francisco school board to rescind an order segregating Japanese schoolchildren in return for a Japanese curb on emigration of peasants and laborers to the United States—the famous “Gentleman’s Agreement.” Shortly afterward, Roosevelt dispatched the American fleet—the so-called Great White Fleet—on a world cruise in a nebulous display of “big-stick” diplomacy. He also made another realistic compromise. In November 1908 the United States implicitly recognized Japan’s economic ascendancy in Manchuria, while Japan reaffirmed the status quo in the Pacific and the Open Door in China. Roosevelt’s views continued to mature during his retirement, and in 1910 he urged President William Howard Taft to abandon commercial ambitions in Manchuria and North China. To wage a successful war there, he warned, “would require a fleet as good as that of England, plus an army as good as that of Germany.”

POST-PRESIDENTIAL YEARS

Roosevelt believed that Secretary of War Taft would continue his own policies unbroken, and he unilaterally put the party machinery behind Taft’s nomination and election to the presidency in 1908.

Immediately after Taft’s inauguration in March 1909, Roosevelt left the country. He went first to Africa to hunt and collect fauna. “I constantly felt while with him,” wrote the naturalist Edmund Heller, with whom he~iater collaborated on Life Histories of African Game Animals (1914), “that I was in the presence of the foremost field naturalist of our time, as indeed I was.” On emerging from the jungle after ten months, Roosevelt offended Egyptian nationalists with a pro-imperialist speech in Khartoum. In Rome a little later he antagonized both the pope and a group of American missionaries. Then, following a triumphal procession through northern Europe highlighted by a meeting with the Kaiser and a Nobel Prize address, he returned home }n June 1910 to a tumultuous welcome.

Source : wikipedia.org

The Bull Moose Movement.

Progressive Republicans soon subjected Roosevelt to enormous pressure to reenter politics. President Taft had conceived it his mission to consolidate the Roosevelt reforms, or, as he privately phrased it, to give them the “sanction of law,” not to embark on new ventures. He especially deplored Roosevelt and Pinchot’s loose construction of the law in conservation matters, and the resultant charges and countercharges had culminated in Pinchot’s forced resignation as chief of the Forest Service while Roosevelt was abroad. Taft’s maladroit effort to revise the tariff—a reform Roosevelt had shrewdly avoided—had further alienated Republican progressives, as had Taft’s apparent support of the Old Guard in Congress.

In these circumstances, Roosevelt’s halfhearted effort to resume friendly relations with Taft and bring the two wings of the Republican party together was foredoomed. Late in the summer of 1910, at Osawatomie, Kans., Roosevelt implicitly dramatized the philosophical differences between himself and his successor in one of the most memorable of his political addresses, “The New Nationalism.” Moving even beyond the progressive themes of the last years of his presidency, he called for greatly expanded welfare and regulatory programs and asserted that the judiciary’s primary obligation was to protect “human welfare rather than . . . property.” Inadvertently, Taft then drove the wedge deeper by authorizing an antitrust suit against the United States Steel Corporation for absorbing, with Roosevelt’s tacit acquiescence, a smaller company during the Panic of 1907.

Roosevelt did not want to run again in 1912. Rut when progressive Republicans threatened to support Senator Lafollette if he rejected their entreaties, Roosevelt reluctantly entered the race for the nomination. The most bitter pre-convention campaign in Republican history followed. Although Roosevelt outpolled Taft overwhelmingly in the primary states, the president’s control of the party machinery enabled his supporters to seat a crucial number of contested delegates at the convention in Chicago. Roosevelt’s delegates, after losing the contest over the election of a temporary chairman and realizing that they were in the minority, stormed out of the hall. Six weeks later they and other Roosevelt supporters returned to form the Progressive party, nominate their hero, and roar approval of his acceptance speech, “Confession of Faith.” The speech synthesized progressive Americans’ aspirations for democracy, elimination of injustice, and the creation of equality of opportunity. “We stand at Armageddon,” Roosevelt declared, “and we battle for the Lord.”

Roosevelt waged a characteristically aggressive campaign, (luring which he was wounded in Milwaukee in an assassination attempt. Rut the moderately progressive Democratic governor of New Jersey, Woodrow Wilson, received 42% of the popular vote and won overwhelmingly in the Electoral College. Roosevelt and his running mate, Gov. Hiram Johnson of California, carried California, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Washington, and drew 27% of the popular vote. Taft won only two states.

From 1912 to 1914, Roosevelt wrote his autobiography, won a libel suit against a Michigan editor who had characterized him as a liar and drunkard, and led an expedition up an unmapped river in Brazil, where he almost died of malarial fever. He also campaigned dutifully but unsuccessfully for Progressive party congressional candidates in the fall of 1914.

World War I.

The outbreak of war in Europe in the summer of 1914 gave Roosevelt a new cause—preparation for American entry. By autumn he sympathized with Belgium and believed that Britain and France had to prevent German domination of the Continent. Yet he also feared that a decisive Allied victory would disrupt the balance of power excessively. These measured views were shortly compounded, however, by his nationalistic reaction against German submarine warfare. By the fall of 1915, Roosevelt had concluded that the United States should enter the war on the side of the Allies. His conclusion was grounded as firmly on opposition to the violation of so-called American rights on the high seas as on a realistic appraisal of the implications of German control of the land mass of Europe.

Too astute to destroy his effectiveness by calling openly for war, Roosevelt spoke passionately for preparedness and against proposals for an arms embargo. He also excoriated President Wilson, denounced “peace at any price” pacifists, and called anti-British ethnic groups disloyal.

Roosevelt hoped that the Republicans and the remnants of the disintegrating Progressive party would come together behind his presidential candidacy in 1916. But his consuming aim was the defeat of Woodrow Wilson. To this end he rejected the Bull Moose nomination when the Republicans nominated U. S. Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes instead of himself. He then campaigned vigorously, though without private enthusiasm, for Hughes, whom he had called a “Wilson with whiskers.” The country sensed that Roosevelt stood for war, and his support of Hughes probably hurt Hughes more than it helped.

After the United States entered the war in April 1917, Roosevelt emerged as the leader of the administration’s constructive, and until the Armistice, loyal opposition. Had he lived he would doubtless have won the Republican nomination in 1920. He longed to die at the head of a division in France. When his plea for a command was refused, he immersed himself vicariously in the military activities of his four sons, the youngest of whom, Quentin, died in air combat. “It is very dreadful that [Quentin] should have been killed,” he wrote; “it would have been worse if he had not gone.”

Source : wikipedia.org

Roosevelt’s attitude toward the impending peace and League of Nations was a curious amalgam of realism and ultranationalism. He ridiculed Wilson’s Fourteen Points as “Fourteen Scraps of Paper,” and he deplored the president’s failure to appreciate the dependence of the United States on British naval’ power. The Royal Navy, he said, “should be the most powerful in the world,” and the United States should not attempt to rival it. Roosevelt further called for unconditional surrender of Germany, preservation of the Monroe Doctriné, and close military relations with the French. He also favored creation of the League of Nations, though as “an addition to,” rather than as “a substitute for” American military preparedness. Three days before his death he endorsed Taft’s proposed reservations to the League, which differed little from his own and from the original reservations supported by Senator Lodge.

Recurring bouts with malarial fever sapped Roosevelt’s strength during his last years. He was also hospitalized with rheumatism. On Jan. 6, 1919, he died at home in his sleep. He was buried without eulogy, music, or military honors in a plain oak casket at Sagamore Hill.

mavi