What is the history and periods of Russian Art And Architecture? The important arts, works and artists of Russian Art And Architecture through history.

Russian Art And Architecture

Russian art has roots, however, in the pagan art of earlier periods and has drawn successively on Byzantine and western European traditions.

The history of Russian art and architecture falls into four major periods, reflecting the divisions of Russian political history—the medieval period of principalities influenced by Byzantine tradition, the Muscovite period dominated by Moscow, the Westernized period initiated by Peter the Great, and the Soviet era. Throughout its development, relatively constant elements in Russian art have been a humanizing tendency, a decorative sense, and patronage by the state.

MIDDLE AGES

The medieval period in Russia had two phases. The earlier, dominated by Kiev, lasted until the Mongol (Tatar) conquest in 1240. The later, which saw the rise of other states, ended with Moscow’s gradual assumption of the role of a Third Rome, after the fail of Byzantium (Con^ stantinople), the Second Rome, to the Turks in 1453.

In the 10th century, the Russians were loosely organized in a federation of largely selfgoverning principalities under the authority in military and foreign affa irs of Kiev, in the Ukraine. At the command of Vladimir, grand duke of Kiev, they abandoned paganism in about 990 in favor of the Orthodox form of Christianity centered in Byzantium. So efficiently did they execute his instructions to destroy ali objects connected with paganism that few vestiges of Russia’s preChristian culture have survived. The exceptions are chiefly jewelry; amulets shaped like female deities, bears, or sun symbols; and stone idols. Certain pagan motifs, however, persisted in folk art, notably the tree of life, the Great Goddess, and animal designs derived from Persia or from the Scythians and Sarmatians, who inhabited southern Russia in early times.

Kiev’s political preeminence was matched by its artistic achievements. Art also flourished in regional capitals, such as Vladimir, Suzdal, and especially Novgorod, which challenged Kiev’s supremacy. Ali these Russian centers looked to Byzantium, source of their new faith, for their arts. Since the maintenance of Orthodoxy was their chief concern, they gave most of their attention to building churches. Russian princes also, however, quickly assimilated the Byzantine concept of kingship and built palaces to express it. But because most medieval secular work has long since perished, the period is represented almost entirely by religious works.

Architecture.

Russia had a scarcity of building stone, but vast quantities of excellent wood were available to anyone for the cutting. Consequently, from pagan times on, wood was used for most building purposes, and Russians were noted for their woodworking skill. They used wood to build churches; modest, square or rectangular dwellings; and, in each city, a kremlin, or citadel, which included a castle or palace and at least one church within its walls. Oak was used to strengthen the walls surrounding the kremlin or the settlement around it and to pave the streets, as in 12th century Novgorod.

As a building material, however, wood has the disadvantages of being perishable and flammable. Therefore, few wooden medieval structures remain. Russian princes, to celebrate their new faith and authority, built their finest churches, monasteries, and palaces of stone. They had to hire Byzantine craftsmen to teach the Russians the new techniques of masonry.

Kiev.

The four earliest cathedrals (in Russia, major, not episcopal, churches) of Kiev were built in the Byzantine style. They had the plan of a Greek cross within a square, rounded apses, barrelvaulted roofs, and a low central dome flanked by several others. Domes, raised on low drums supported by squinches (arches) poised on piers or columns, were one of the most important Byzantine innovations to reach Russia. Interiors glowed with mosaics of glass, marble, stone, or brick tesserae and with frescoes.

Three of these Kievan cathedrals were destroyed or greatly damaged—Vladimir’s Church of the Dime (Tithe; begun 989), by the Mongols; the Church of the Dormition (Assumption; begun 1073) in Pecherskaya Lavra (Monastery of tlıe Caves), in World War II; and the sumptuous Church of St. Michael (begun 1108) in the MikhailZlatoverkh (Dmitrov) Monastery, in the Stalinist era.

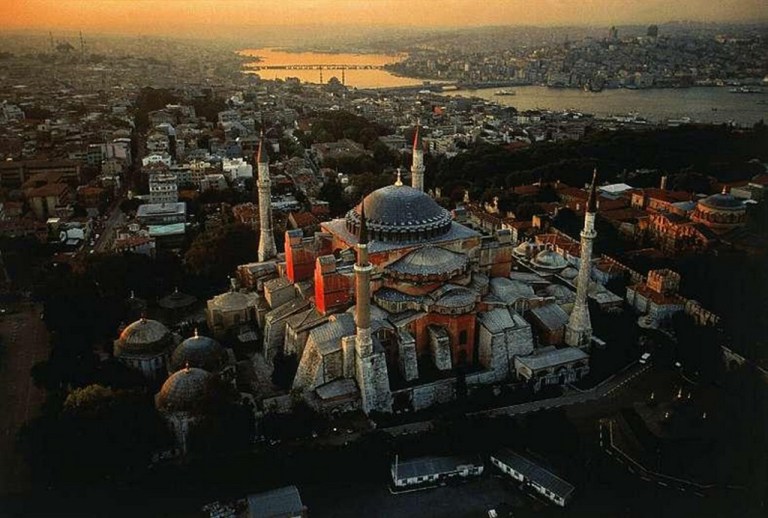

Hagia Sophia

The fourth, Grand Duke Yaroslav’s Cathedral of Hagia Sophia (“Divine Wisdom,” commonly St. Sophia; begun 1036), counterpart of Hagia Sophia in Byzantium, had its exterior altered in the baroque period but retains much of its original interior splendor. Unlike the small llth century Byzantine churches, generally with three aisles and fîve domes, Yaroslav’s church had flve aisles and a large central donıe, symbolizing Christ, surrounded by 12 smaller ones representing the apostles. Also, it was edged on three sides by a peristyle and had towers at the west corners containing stairs to the ruler’s pew in the west gallery. The latter innovation was retained in the 12th century palace at Bogolyubovo.

Vladimir Suzdal

In the late 12th century, regional capitals, such as Chernigov and Smolensk, built fine cathedrals on modified Byzantine lines. In the principality of VladimirSuzdal there evolved a distinctive style, whieh survives in a series of small churches of great elegance. They are cruciform in plan, their three aisles terminate in apses of full height, and their single domes rest on drums slenderer than those of Kiev. Each of the outer walls is divided into three vertical sections by some flat feature, such as a pilaster, and each is adorned with sculptured motifs of a fîgural, vegetal, or geometric character unique in Russian art. These churches are also interesting for their Romanesque elements stemming from the Western world. Representative of the fully developed style is the ornate Cathedral of St. Dmitri (begun 1193) in Vladimir.

Vladimir-Suzdal White Monuments

Novgorod and Pskov.

The architecture of Novgorod was launched by Vladimir of Kiev, who commissioned a cathedral dedicated, like that in Kiev, to Hagia Sophia. Built of oak and roofed with “13 tops” (probably meaning “turrets”), it burned in 1045. A new stone replacement (completed 1052) is less ornate than Kiev’s Hagia Sophia, having 3 aisles instead of 5, and 5 domes instead of 13. However, its plain, whitewashed, monolithic exterior, ornamented only by pilasters and a scalloped motif on the drums, already reflects Novgorod’s fondness for simplicity and verticality. The stress on verticality is even stronger in the Cathedral of St. George (begun 1119) in the Yuriev Monastery built by Master Peter. Here the facades have the threefold division of VladimirSuzdal, and tlıe domes are slightly pointed and reduced in number to three.

Novgorod, which had ceased to be dependent upon Kiev in the llth century, escaped conquest by the Mongols. After a lull of a century, the arts regained their original impetus, and trade with the West expanded. New churches were built in a modification of the Novgorodian style. The threefold facade wa$ retained, with restrained lowrelief decoration. But tire overall shape became cubelike, as the side apses, which had already been reduced in height and circunıference in the exquisite Church of the Savior in nearby Nereditsa (1198; destroyed in World War II), gradually disappeared. Examples are the churches of St. Theodore Stratelates (about 1360) and Our Savior of the Transfîguration (1372), whose blind arcading on the remaining apse may reflect Western influence.

Church of the Savior

Roofs also changed, becoming completely vaulted, forming a scalloped or triangularshaped gable on each side. Domes, usually single, stood on tali drums and gained a helmlike silhouette, whieh was later replaced by an onion shape, originating in Moscow. Freestanding, multistory towers were built for bells, new to Russia.

Like Novgorod, its satellite Pskov escaped the Mongols and also built ne w churches. They were small, with large porches and short, squat, waisted columns flanking the entrance to the nave. These churches were the earliest in whieh pendentives (spherical triangles) rather than squinches support the drum. Bell towers were similar to those in Novgorod.

The most advanced example of postMongol secular building was the stone palace built by Archbishop Vasili in Novgorod (1433). its simple exterior contrasts sharply with the decorative brickwork of the princely palace in Uglich (1481), built in the Muscovite style. The Pogankiny mansion in Pskov, a rare example of a 17th century merehant’s residence, suggests the domestic style of earlier centuries.

Painting.

Medieval Russian painting ineludes frescoes, icons, and illumination, mostly done by monks. Like architecture, it was strongly influenced by Byzantine tradition in its formal, unrealistic, frontal style and religious sııbject matter and symbolism, but over the centuries it developed national and regional modifications.

Frescoes.

The Byzantine artists who went to Kiev to adorn its churches were assisted by Russians, who made their influence felt even before they were able to replace their masters. As a result, although mosaic murals were never combined with painted ones in Byzantium, both mosaics and frescoes adorn the walls of Kiev’s Hagia Sophia. Although they conform to Byzantine tradition, the humanistic element clıaracteristic of Russian art is already apparent, as, for example, in the fresco portraits of Yaroslav’s family (about 1045) in the nave, in contrast to the formality of contemporary Byzantine court portraiture. The early 12th century frescoes in Hagia Sophia’s two towers are equally unique in Russian and Byzantine art for their secular content. One depicts the Byzantine emperor ı watching the hippodrome races. Others illustrate hunting, court, or theatrical scenes.

The early artists of Vladimir-Suzdal and Rostov drew on Kiev for inspiration and, at first, also worked under Byzantine masters. In the great fresco of the Last Judgment (begun 1194) in the Cathedral of St. Dmitri in Vladimir, a Byzantine master must have painted the 12 Apostles and the angels to their right, while the remaining angels appear to have been done by Russians.

Elsewhere Russians were producing works of great distinction. For example, the frescoes in the Church of the Savior in the Mirozhsky Monastery (1156), near Pskov, possess the intimacy and deep emotional content typical of the Pskovan school. Those adorning Pskov’s Snetorgorsky Monastery (1313) display a spontaneity that was also characteristic of the region.

The finest work was done on Novgorodian territory. The frescoes in the Church of St. George in Staraya Ladoga (about 1167) display the clear lines and sense of movement that distinguish painting of the Novgorodian school. The Last Judgment in the Church of the Savior in Nereditsa was especially fine.

Byzantine influence revived in Novgorod with the arrival there about 1370 of the great Byzantine master Theophanes £he Greek (Feofan Grek). Fragments of his murals in the Church of Our Savior of the Transfiguration show his elongated figures, subtle color, complex composition, and nervous, strongly highlighted style. His influence was reflected in the Russianpainted murals in the Dormition Cathedral in Volotovo (1380; destroyed in World War II). The latter contrasted with the contemporary, Macedonianin fluenced frescoes in the Church of the Savior in Kovalevo (destroyed in World War II).

Dormition Cathedral

By 1395, Theophanes was in Moscow, where he worked with Russian artists. He adorned the Church of the Birth of the Virgin, with the help of Semyon the Black and pupils; the Cathedral of the Archangel; and, with Prokhor of Gorodetz and the monk Andrei Rublev, the Annunciation Cathedral. During these years he also decorated the ducal palace with topographical and historical frescoes.

Rublev, an artist of great sensitivity and lyricism, the Fra Angelico of Russia, created the Muscovite school of painting. Examples of his frescoes are those painted with Daniil Chernyi in 1408 in the Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir.

Icons.

Icons, religious panel paintings representing holy beings, were created for homes and for churches, especially for the high carved iconostasis (screen) introduced in the 14th century. Few survive from before the Mongol conquest, none definitely ascribed to Kiev. Although they adhere to Byzantine tradition, including the use of gold or silver for background and regalia, Russian elements are so much in evidence that few, even of the earliest icons, can be taken for Byzantine. Icons from VladimirSuzdal and Yaroslavl possess a patrician quality, which disappeared with the Mongol invasion. Novgorodian icons, which form the great majority, reflect the sturdier, more forthright outlook of a merchant people.

Of icons after the Mongol conquest, those of the Novgorodian school in the 14th and 15th centuries maintained such a high standard that they represent the classical period in Russian icon painting. Their rhythmic, linear qualities, superb, brilliant colors, deep spirituality, and elimination of ali unnecessary details stamp even the most Byzantineinfluenced icons with the Novgorodian hallmark.

About the same time, the Moscow sehool of icon painting was developing, especially ıınder Rublev. His rhythmical style, seen at its purest in the Old Testament Trinity (Tretyakov GaJlery, Moscow), is distinguished by soft and delicate, yet precise and flrm outlines; by the preponderance of curved lines unobtrusively contrasted with angular lines; by the sloping shoulders of his fîgures; and by clear, luminous, pastel colors. Other Muscovite painters acquired Rublev’s elegance, combining it with brown flesh tints, multiple highlights, and elaborate architectural backgrounds. After Moscow’s annexation of Novgorod in 1478, these elements, but without the elegance, began to influence and undermine the Novgorodian style.

Illumination.

In book illumination, mostly religious, the RussoByzantine style was inspired by Byzantine tradition, yet, especially in Novgorod, it often incorporated nonByzantine elements. These included elaborately interlaced initials, possibly influenced by Norse design; whole or truncated animals recalling Celtic, Romanesque, Russian, or even Scythian forıııs; and floral and geometric Russian motifs. Examples are the Svyatoslav Codex of 1073 and the exceptionally fine Khitrovo Gospels, perhaps by Rublev.

Decorative Arts—Metalwork.

The tradition of metahvork in Russia is at least as old as the metal ornaments in a spirited animal style created by the Scythians. The pagan Slavs were too poor to work costly metals, but Kiev’s Christian artisans produced for the church and the nobility exquisite vessels, jewelry, and other articles of filigree and cloisonne enamel on copper or gold. Cloisonne plaques for personal adornment were generally round or boat shaped, with Russianinspired floral, geometric, or bird motifs. Religious plaques resembled their Byzantine prototypes.

The Vladimir Suzdalian metalworkers produced superb damascene work, seen at its best in the 13th century panels of the doors of the Nativity Cathedral in Suzdal. The greater part of their output was chalices, censers, crosses, and book and icon covers for the church. Novgorod fashioned some vessels of distinctive scallop shape, with decorations sometimes showing Western influences.

Embroidery.

Fine embroidery was made in convents from early medieval times. Most of the best work was for the church and followed Byzantine styles, but with regional modification. Commemorative portrait hangings, such as that of Saint Sergius of Radonezh, were embroidered in palace workshops from the 15th century.

MUSCOVITE PERIOD

In the 14th century, Moscow gradually began to emerge as the unifying force among the Russian principalities, most of which were stili subject to Mongol rule. Dmitri Donskoy’s victory over the Mongols at Kulikovo in 1380 quickened Moscow’s creative spirit. its prestige was enhanced by its assumption of leadership of the Orthodox community after the fail of Byzantium and by the marriage in 1472 of Ivan III to the niece of the last Byzantine emperor. Muscovite art reflected this rise in Moscow’s fortunes.

Architecture—Wood.

Muscovite stone architecture was greatly influenced by the long tradition of Russian architecture in wood. Although no medieval wooden buildings survive, churches of the 17th and 18th centuries faithfully reproduced the forms of the much older churches they replaced. They fail into four major types.

The first and most common was the cellular type. The church was raised on a substructure of storerooms and was surrounded by covered verandas reached by roofed staircases. The steeply pitched roof had at its center a small drum and dome or steeple, as in St. John’s Church, near Rostov.

The second, or tent type, had a steeple shaped like a pyramid or tent. The steeple rose from amidst kokoshnik gables, socalled because their aceofspades shape resembled a kokoshnik, or medieval woman’s headdress. These gables made a transition from the rectangular body of the church to the octagonal drum under the steeple, as in St. Clement’s Church, at Una.

The third type had a tiered roof. On each facade, three or more tiers projected in rows of inverted shaped gables, and an onionshaped dome on a drum rose from the top, as in the Church of St. John the Forerunner in the Penovsky district.

The fourth and most spectacular type was multidomed. Each dome, piled in a central mass, rose from a shoal of kokoshnik gables, as in the Church of the Transfiguration in Khizi.

These churches, regardless of their extemal differences, were divided intemally into three sections—the trapeza, nave, and chancel. The trapeza was a low anteroom where worshipers could assemble for warmth, food, and talk. It was separated from the much higher nave by a thick wall designed to deaden the noise in the anteroom, but with slits cut in it to enable the overflow on feast days to follow the service. The nave was separated from the chancel by the iconostasis, whose central, or “Royal,” doors revealed the altar.

An example of medieval and Muscovite domestic architecture is the palace at Kolomenskoe, near Moscow, built by Ivan I in the 14th century, subsequently rebuilt, and later destroyed. Known through early sketches and an 18th century model, it consisted of a series of square and rectangular sections under kokoshnik gables and tentshaped turrets or steeply pitched roofs. The whole complex was as picturesque as an English halftimbered Elizabethan mansion, though less well ordered. Nobles’ and merchants’ houses followed a similar plan, including, for example, the mansion of the Stroganovs in Solvychegodsk, near Perm. Storerooms were on the ground floor and quarters for women and children on the top.

Stone.

Muscovite stone architecture developed in the late I5th century, when Ivan III imported four Italian arehiteets—Aristotele Fioravanti, Alevisio Novi, Marco Ruffo, and Pietro Solari—to strengthen the Kremlin with modern gunfireresistant walls. He also employed them within the Kremlin but insisted that there they follow traditional Russian architecture.

The Kremlin’s churches are a microcosm of the religious stone architecture of late 15th and early 16th century Muscovy. The VladimirSuzdalian style prevailed in the Dormition Cathedral (begun 1475), built by Fioravanti after Ivan had sent him to study the churches of Vladimir, and in the Annunciation Cathedral (begun 1482), built by masons from Pskov and one of the first churches to copy wooden kokoshnik gables in stone. Pskovians also built the Cathedral of the Ordination (begun 1485), but in their native style.

Kremlin

In the Cathedral of the Archangel Michael (begun 1505), Novi combined such Russian basic elements as the cruciform interior ground plan and onionshaped domes with such Renaissance decorative features as classical capitals, a cornice, and a row of flat, semicircular, fluted niches. The elegance of Moscow’s developed omamental styles is seen in the Church of the Savior Behind the Golden Lattice (1678). The original Terem Palace, also in the Kremlin, and the Old Printing House, in Moscow, are examples of secular Muscovite architecture.

A very different note is struck by two other important Kremlin buildings. The banqueting hail by Rulfo and Solari, called the Palace of Facets (begun 1487) after its faceted stone facade, is unique for its Italianate design. The novel beli tower of Ivan Veliky (begun 1532), built by the Italian Marco Bono, consists of Westerninspired, recessed, corniced tiers, whose outline was nonetheless attuned to that of the wooden tentehureh.

The resemblance may have been intentional. For in 1532, Vasili III celebrated the birth of the future Ivan IV by building in Kolomenskoye the Church of the Âscension, which copied in masonry the features of wooden churches. Resting on a substructure, it is surrounded by verandas reached by covered staircases and is roofed with a tentsteeple rising from a cluster of superimposed kokoshnik gables.

The Church of the Ascension launched a style of tentroofed churches on a rectangular or octagonal plan, which quickly became so popular that in the nıid17th century Patriarch Nikon, zealously determined to maintain Byzantine traditions, forbade it in favor of domed churches. Fortunately two churches, which combined tentroofs and domes and elaborated them in the baroque spirit, escaped his ban. They are the Church of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist in Dyakovo (begun 1553) and the brightly painted Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed (begun 1555) in Moscow’s Red Square.

Nikon’s ban did not apply to churches built in the baroque style introduced through Poland and the Ukraine. Of two kinds, the more conservative were omate yet basically traditional, as, for example, St. Nicholas Church in Khamovniki, Moscow (late 16th century), where the profuse decoration, chiefly around windows and doors, was a new departure. The Westernized baroque churches, such as those of the Intercession of the Virgin in Fili (1693), in a Moscow suburb, and of the Virgin of the Sign in Dubrovitzy (begun 1690), modified traditional forms. The cruciform interior plan is repeated on the exterior, with its four projecting arms rounded and an octagonal tower at its center. The Fili church is tiered, and its recessed superstructures are enlivened with domes. The Dubrovitzy church is onestoried, but its roof is omamented with statues, never before so used. Neither of these baroque tendencies, however, continued.

Painting—15th and 16th Century Frescoes and Icons.

The school of Moscow was at its height in the late 15th century under Dionysius, the third of the great masters of Russian painting, after Theophanes and Rublev. Working with his two sons and a team of artists, he frescoed the interiors of the Dormition Cathedral in Moscow and the Therapont Monastery and others and produced many icons. His fresco colors are light and gay, those in icons more subdued. In both forms his work, as a professional painter rather than a monk, is to some extent individualized in style. It is dramatic, and it reflects a new interest in aesthetics, perhaps influenced by the Italian architects in Moscow, and in depicting movement. Dionysius’ profusely highlighted figures have small features, slender, elongated bodies, and swirling drapery. His backgrounds contain complex architectural compositions.

During the 16th century, new, often didactic themes appeared gradually in Muscovite icons, and several sequential scenes were presented on one panel. Although the reformminded Council of the Hundred Chapters (15501551) . advocated a return to Novgorodian tradition, and some artists complied, Muscovite tendencies generally continued. Panels became smaller, duller in color, and more crowded with additional fîgures and detail.

17th Century Icons and Murals.

Toward the end of the 16th century, connoisseurs of icons sponsored a new style in the icons of the Stroganov school, by such men as Procopius Chirin and Istoma and Nazari Sawin. Trained in the workshops established by the Stroganov family in Solvychegodsk, they had developed a distinctive style while painting for the czar and the nobility in the Moscow Kremlin. Their jewellike icons were in a richly colored, highly detailed, miniaturist style, with highlights in gold. Fine icons continued to be made after 1640 in the Palace of Arms (Armory), which had become the artistic center of the country.

By the beginning of the 17th century, naturalism, as a result of Western influence, was already attracting Russian painters. Despite church opposition, they began to experiment with portraiture, realistic perspective, genre, and the naturalististic style, as seen in the icons of Simon Ushakov, Moscow’s foremost artist. From about 1630, certain icons memorializing individuals— icons called parsnuyas from the Latin persona, or person—were a blend of traditional iconic and new Western trends.

Illumination and lllustration.

Religious works in the 15th and 16th centuries continued to be illuminated in the RussoByzantine style. Works, such as the Tale of Mamaev, were illuminated in the RussoByzantine style in the 15th century. From the 16th century their painted illustrations reflect the influence of Westerninspired woodcuts by incorporatmg details of contemporary life.

Decorative Arts—Metalwork.

Muscovite metalwork surpassed ali previous Russian achievements, as skilled craftsmen in the Palace of Arms worked for the czar, the nobility, and the church, and the metalworkers’ guild catered to the growing merchant class. In addition to religious articles, they produced a wide range of domestic wares, most characteristically lovingcups, wine tasters, and goblets. Such objects were made of plain or gilded copper, iron, silver, or gold and were often decorated with niello, repousse, and vividly colored enamels.

Carving.

Wood carving, at which the Russians have always excelled, flourished both as a professional and as a folk art. The forms and motifs of the Muscovite period recall earlier ones and continued into the early 20th century. Most professional carving was done for the church, as, for exanıple, the Ludogoshchinsky Cross (1366). Figures in the round are rare, as a result of the Byzantine prohibition against statuary, but almost lifesize figures in very high relief are remarkable for their religious intensity. Many iconostases were exquisitely carved and painted, sometimes gilded, and fine work was lavished on church gates, the shingles of domes, and burial crosses.

Folk carving was chiefly on secular objects— carts, boats, furniture, looms, shuttles, tableware, stamps for decorating textiles and gingerbread, toys, and the frames of doors and windows. Motifs inciuded vegetal and geometric forms and real and mythical animals.

Ceramics.

Much excellent pottery had been made in Kiev, but after the Mongol invasion nothing of quality was produced anywhere in Russia until the late 16th century. From that time, Yaroslavl and Moscow made fine glazed tiles with pictorial designs to decorate churches and houses and the stoves used for heating.

Embroidery.

In the Muscovite period many rich robes for clergy and nobility were embroidered in gold and silver tiıread to resemble imported brocades and velvets. Peasant women did crossstitching or drawnwork on clothes and household linen, often using animal forms and the ancient treeoflife and Great Goddess motifs.

WESTERNIZED PERİOD

As the early rulers of Kiev had been determined to transform Russia from a pagan to a Christian country, so Peter the Great set himself to propel Russia from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. As the Kievans turned to Byzantium for art and artists, so Peter looked to the West, importing artists and sending Russians to study abroad. His Westernizing policy ended the domination of religious art, just as his transfer of the capital to St. Petersburg (Leningrad) ended Moscow’s political supremacy.

Architecture.

Although Peter’s Westernization had little effect on wooden peasant architecture, it greatly changed the style of churches, palaces, and country houses.

Early 18th Century.

Aided by his first, and foremost, imported architect, the SwissItalian Domenico Trezzini, Peter began to build his new capital in 1703 on the Gulf of Finland, confronting the Westem world. He was in such haste that he forbade building in stone and brick in the rest of Russia, and he often obliged both his foreign and Russian architects to complete work begun by a colleague. The city, planned by Trezzini and successively altered by the Frenchman A. J. B. Le Blond and the Russian P. M. Yeropkin, had a regular plan in the contemporary Western manner in contrast to the haphazard Russian cities. The architecture was Petrine baroque, a restrained blending of Peter’s taste with Trezzini’s interpretation of Dutch baroque, familiar to Peter from his travels abroad.

The first structure was Trezzini’s citadel, the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, with its great gate and cathedral surmounted by a beli tower and spire. The buildings on which Peter set most store were the wharves and the spirecrowned admiralty by I. K. Korobov, administrative buildings such as Trezzini’s Twelve Colleges, and the three standardized types of houses that Peter had devised for the three social classes of the town’s citizens. Other structures included the Kunstkamera (Cabinet of Curios) for Peter’s collections, by the German G. J. Mattarnovi, and buildings by M. G. Zemtsov, Yeropkin, and other Russians.

St. Petersburg was more famous, however, for its palaces. That of Prince Menshikov at Oranienbaum, probably designed by the German Andreas Schluter, was begun by J. G. Schâdel and rebuilt in the late 18th century by Antonio Rinaldi. Schluter may ha ve designed Peter’s intimate Summer Palace, built by Trezzini, Schluter, and Schâdel, with Peter himself doing much of the paneling. The great palace at Peterhof (Petrodvorets), with its formal gardens and fountains, was begun by Le Blond, architect of Louis XIV, on the pattern of Versailles and completed by J. F. Braunstein. On its grounds were the small palaces Mon Plaisir, possibly designed by Schluter, and Marly, both built by Braunstein.

Late 18th and 19th Centuries.

Although St.Petersburg remained essentially Peter’s creation, it was further adorned in the mid18th century by his daughter Elizabeth and her Italian architect, B. F. Rastrelli. He built palaces in an exuberant, strongly individual style that mixed baroque, rococo, and Russian elements. They generally had long facades broken by pillars and other details and covered with brightly colored stucco set off by white. Examples include the Winter Palace (originally begun for Peter), the Stroganov Palace, the Smolny Monastery complex, and, on the outskirts of the city, the enlarged palace at Peterhof and the Cajherine Palace (named for Peter’s wife) at Tsarskoye Selo (Pushkino).

In the late 18th century, Catherine the Great, who loved Roman architecture, imposed a more severe, neoclassical style. Using Russian and foreign architects, she commissioned such structures as the Hermitage Theater and the completion of the Catherine Palace, by Giacomo Quarenghi; the gate over the New Holland canal, by J. B. Vallin de la Mothe; the Tauride Palace, by I. E. Starov; and the palace in Pavlovsk (Detskoye Selo), by Charles Cameron.

Where Catherine’s buildings held an uneasy balance between the sedate work of Peter’s architects and the ebullience of Elizabeth’s, it took the genius of the Russianborn Italian Carlo Rossi to achieve complete cohesion. He worked at the beginning of the 19th century for Alexander I, who was even more of a classical purist than Catherine, deriving his siyle from Greece rather than Rome. Rossi coordinated the main buildings of the capital by designing splendid General Staff buildings to form the Palace Circus in front of the Winter Palace and by creating the brilliant Senate Square to the west.

In the same period, Thomas de Thomon built the stock exchange on the lines of a Greek temple. A. D. Zakharov designed the more original Admiralty building, between the Winter Palace and Senate Square, which cleverly retained the spire from Peter’s Admiralty. Good neoclassical work was stili produced in the reign of Nicholas I, but the growth of the Slavophile movement led to the revival of the 17th century Muscovite style.

Painting and Graphics.

Although icon painting continued as a local tradition, the major development in the capital was Westernized art. The Russians were especially outstanding in portraiture and graphics.

Portraiture.

The striving for veracity and emotional intensity, already evident in icons, continued in portraiture. True portraiture, produced in Moscow at the end of the 17th century but lacking in modeling, acquired polish and distinction only in St. Petersburg, under Peter’s insistence, in the hands of I. M. Nikitin and A. M. Matveev. Only with D. G. Levitsky, a generation later, did it attain full artistry.

Russian forthrightness and the resulting intimacy are evident in the work of ali these men, but especially in V. L. Borovikovsky’s portrait of Catherine II walking her greyhound Tom. This work is in sharp contrast to the formal royal portraits of the West. The same spirit permeates the works of Russia’s only truly great native sculptor, F. I. Shubin. Early 19th century portraitists, such as O. A. Kiprensky, were inflııenced by Byron and the Romantic movement.

Realism and the AvantGarde.

The growth of a social conscience, stimulated by such political events as the Napoleonic Wars and the Decembri’.t rising of 1825, led to a semisatirical, semirealistic movement in art, as, for example, in the paintings of P. A. Fedotov and V. G. Perov. After the Crimean War and the reforms of Alexander II, reformminded artists led by I. N. Kramskoy founded the Society of Wanderers (Peredvizhniki) in 1870. Their purpose was to hold traveling exhibitions of realistic paintings revealing existing social evils. However, I. Y. Repin, the foremost realist painter, was never a member.

At the end of the 19th century, artists opposed to realism and interested in their European heritage, inchıding A. N. Benois, L. S. Bakst, M. V. Dubozhinsky, M. F. Larionov, N. J. Goncharova, and the art patron Diaghilev, formed the World of Art (Mir Iskusstva) society. Taking the slogan “art for art’s sake,” they were the first Russians to concern themselves wholly with aesthetics rather than with spiritual meaning or with subject matter. Their stylized, exotic, brilliantly colored sets for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes transformed the European stage.

The Revolution of 1905 encouraged some artists to desire as much of a transformation in art as the terrorists did in politics. In their efforts to express the essence of their subject matter rather than its form, they discarded realism in favor of Frenchinspired cubism and other avantgarde movements. Larionov and Goncharova explored futurism and developed rayonism, which explored light radiating from objects. K. S. Malevich invented suprematism, an art movement dealing with basic geometric fornıs that led eventually to late 20th century minimal (primarystructure) art. Naum Gabo, Anton Pevsner, V. Y. Tatlin, and El Lissitzky developed constructivism, sculpture by assemblage uıat tried to incorporate movement. Wassify Kandinsky’s emotionally inspired, nonobjective paintings contributed immeasurably to abstract expressionism.

Graphic Arts.

As a part of the Westernizing process, Peter the Great encouraged the printing of books for both the quality and the mass market, many of them illustrated by naturalistic engravings. Many of the finer books were adorned with marvelously decorative chapter headings and tailpieces. In the 20th century, book illustration reached new heights of aesthetic achievement in the work of such World of Art members as Goncharova.

In the 18th century the popularity of the cheapest books was eclipsed by that of the lubok, or broadsheet. Decorated at flrst by woodcuts, later by engravings or lithographs, and often colored, they conveyed religious, political, and satirical subjects or simply songs and stories.

Decorative Arts.

Russian metalwork of the 18th century included exquisite snuffboxes with painted enamel portraits and scenes. Craftsmanship perhaps reached its peak in the enameled and jeweled objects by the 19th century court jeweler K. G. (or Cari) Faberge.

After much effort by Peter and Elizabeth, D. I. Vinogradov finally discovered the secret of porcelain. The Imperial Porcelain Manufactory was founded in St. Petersburg in 1750 and expanded by Catherine. It produced figurines, which became famous, and tablewares with armorial designs and, later, views and military subjects. Other porcelain factories were soon established.