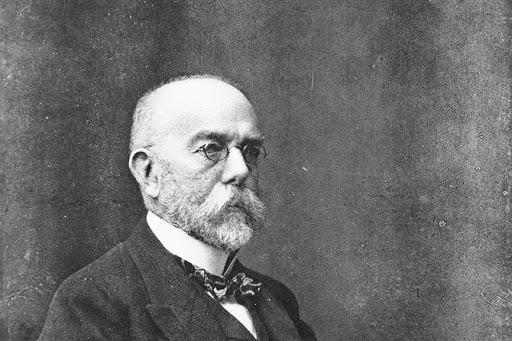

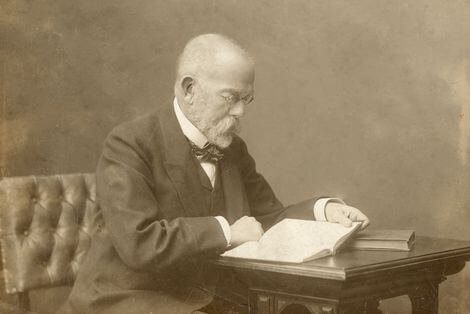

Robert Koch was a renowned German bacteriologist and biologist who made significant contributions to the field of microbiology. Learn about his life and achievements in this biography. Who was Robert Koch?

Robert Koch was born on December 11, 1843 in Clausthal, in the Upper Harz Mountains. Son of a mining engineer, he astonished his parents at the age of five by telling them that, with the help of newspapers, he had taught himself to read, a feat that presaged the intelligence and methodical persistence that would be so characteristic of him in the later life. He attended the local high school (“Gymnasium”) and showed interest in biology and, like his father, a great drive to travel.

In 1862 Koch went to the University of Göttingen to study medicine. Here the Professor of Anatomy was Jacob Henle and Koch was undoubtedly influenced by Henle’s point of view, published in 1840, that infectious diseases were caused by living organisms and parasites. After obtaining his Doctor of Medicine degree in 1866, Koch went to Berlin for six months of chemical study and there he was under the influence of Virchow.

In 1867 he was established, after a period as an assistant in the General Hospital of Hamburg, in general practice, first in Langenhagen and shortly after, in 1869, in Rackwitz, in the province of Posen. Here he passed the examination of the District Medical Officer. In 1870 he volunteered for service in the Franco-Prussian War and from 1872 to 1880 he was district medical officer for Wollstein. It was here that he carried out the investigations that made epoch and that placed him in a first place in the front of the scientific workers.

Anthrax was, at that time, predominant among farm animals in the district of Wollstein and Koch, although it had no scientific equipment and was isolated completely from libraries and contact with other scientists, it embarked, despite the demands that he did his busy practice, in a study of this disease. His laboratory was the four-room apartment that was his home, and his equipment, apart from the microscope his wife had given him, had been fixed by himself. Before, the anthrax bacillus had been discovered by Pollender, Rayer and Davaine, and Koch set out to prove scientifically that this bacillus is, in fact, the cause of the disease.

He inoculated mice, by means of homemade wood chips, with anthrax bacilli taken from the spleen of farm animals that had died of anthrax, and discovered that these mice were all killed by the bacilli, while the mice were inoculated at the same time. time with the spleen blood of healthy animals did not suffer from the disease. This confirmed the work of others who had shown that the disease can be transmitted through the blood of animals suffering from anthrax.

But this did not satisfy Koch.

I also wanted to know if anthrax bacilli that had never been in contact with any type of animal could cause the disease. To solve this problem, he obtained pure cultures of the bacilli by cultivating them in the aqueous humor of the porthole. By studying, drawing and photographing these cultures, Koch recorded the multiplication of bacilli and observed that, when conditions are unfavorable to them, they produce within themselves rounded spores that can withstand adverse conditions, especially lack of oxygen and that, when the right conditions of life is restored, the spores give rise to bacilli again. Koch cultivated the bacilli for several generations in these pure cultures and showed that, although they had not had contact with any type of animal, they could still cause anthrax.

The results of this meticulous work were demonstrated by Koch to Ferdinand Cohn, professor of Botany at the University of Breslau, who called a meeting of his colleagues to witness this demonstration, including Professor Cohnheim, Professor of Pathological Anatomy. Both Cohn and Cohnheim were deeply impressed by Koch’s work and when Cohn, in 1876, published Koch’s work in the botanical journal of which he was editor, Koch immediately became famous. He continued, however, to work in Wollstein for four more years and during this period he improved his methods of fixation, staining and photography of bacteria and did a more important work in the study of diseases caused by bacterial infections of wounds, publishing his results in 1878. In this work he provided, as he did with anthrax, a practical and scientific basis for the control of these infections.

However, Robert Koch still did not have the right conditions or conditions for his work, and it was not until 1880, when he was appointed a member of the “Reichs-Gesundheitsamt” (Imperial Health Office) in Berlin, that he was provided, first with a narrow and inadequate room, and then with a better laboratory, where he could work with Loeffler, Gaffky and others, as his assistants. Here Koch continued to refine the bacteriological methods he had used in Wollstein.

He invented new methods – “Reinkulturen” – to cultivate pure cultures of bacteria in solid media, like potato, and in agar kept in the special type of flat dish invented by his colleague Petri, which is still in common use. He also developed new bacterial staining methods that made them more easily visible and helped identify them. The result of all this work was the introduction of methods by which pathogenic bacteria could be obtained simply and easily in pure cultures, free of other organisms and through which they could be detected and identified. Robert Koch also established the conditions, known as Koch’s postulates, which must be fulfilled before it can be accepted that certain bacteria cause particular diseases.

About two years after his arrival in Berlin, Koch discovered the tuberculosis bacillus and also a method to grow it in pure culture. In 1882 he published his classic work on this bacillus. He was still busy with work on tuberculosis when he was sent, in 1883, to Egypt as Leader of the German Commission against Cholera, to investigate an outbreak of cholera in that country. Here he discovered the vibrio that causes cholera and brought pure cultures of it to Germany. He also studied cholera in India.

On the basis of his knowledge of the biology and mode of distribution of cholera vibrio, Robert Koch formulated rules for the control of cholera epidemics that were approved by the Great Powers in Dresden in 1893 and formed the basis of the methods of control that are still used today. His work on cholera, for which he was awarded a prize of 100,000 Deutschmarks, also had an important influence on plans for the conservation of water supplies.

In 1885, Robert Koch was appointed professor of Hygiene at the University of Berlin and director of the newly created Hygiene Institute at the University. In 1890 he was appointed General Surgeon (Generalarzt) Class I and Freeman of the City of Berlin. In 1891 he became Honorary Professor of the Faculty of Medicine of Berlin and Director of the new Institute of Infectious Diseases, where he was lucky to have among his colleagues men like Ehrlich, von Behring and Kitasato, who made great discoveries.

During this period, Robert Koch returned to his work on tuberculosis. He sought to stop the disease by means of a preparation, which he called tuberculin, made from cultures of tubercle bacilli. He made two preparations of this type called the old tuberculin and the new, respectively, and his first communication on the ancient tuberculin aroused considerable controversy.

Unfortunately, the healing power that Koch claimed for this preparation was very exaggerated and, because the hopes raised by him were not met, the opinion was against and against Robert Koch. The new tuberculin was announced by Koch in 1896 and the healing value of this was also disappointing; but it led, however, to the discovery of substances of diagnostic value. While continuing this work on tuberculin, colleagues from the Institute of Infectious Diseases, von Behring, Ehrlich and Kitasato, carried out and published their work of creation of time on the immunology of diphtheria (see the biographies of Ehrlich and von Behring) .

In 1896, Robert Koch went to South Africa to study the origin of rinderpest and although he did not identify the cause of this disease, he managed to limit the outbreak by injection into a pool of healthy bile from the infected bladder. animals. Then he followed work in India and Africa on malaria, sewage fever, surra of cattle and horses and plague, and the publication of his observations on these diseases in 1898. Shortly after his return to Germany he was sent to Italy and the tropics where he confirmed the work of Sir Ronald Ross in malaria and did useful work on the etiology of the different forms of malaria and their control with quinine.

It was during these last years of his life that Robert Koch came to the conclusion that the bacilli that caused human and bovine tuberculosis are not identical and his statement of this view at the International Medical Congress on Tuberculosis in London in 1901 caused much controversy and opposition; but now it is known that Koch’s opinion was correct. His work on typhus led to the idea, then a new one, that this disease is transmitted more frequently from man to man than drinking water and this led to new control measures.

In December 1904, Robert Koch was sent to East Africa to study east coast fever on the east coast and made important observations, not only on this disease, but also on pathogenic species of Babesia and Trypanosoma and on spirochetosis transmitted by ticks, continuing his work in these organisms when he returned home.

Robert Koch received numerous awards and medals, honorary doctorates from the Universities of Heidelberg and Bologna, honorary citizenship of Berlin, Wollstein and his native Clausthal, and honorary memberships of learned societies and academies in Berlin, Vienna, Posen, Perugia, Naples. and New York. He was awarded the German Order of the Crown, the Grand Cross of the German Order of the Red Eagle (the first time this high distinction was granted to a doctor), and Orders of Russia and Turkey. Long after his death, he was honored posthumously by memorials and in other ways in several countries.

In 1905 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. In 1906, he returned to Central Africa to work on the control of human trypanosomiasis, and there he reported that atoxyl is as effective against this disease as quinine against malaria. From then on, Koch continued his experimental work in bacteriology and serology.

In 1866, Robert Koch married Emmy Fraats. She gave birth to her only daughter, Gertrud (born 1865), who became the wife of Dr. E. Pfuhl. In 1893, Koch married Hedwig Freiberg.

Dr. Robert Koch died on May 27, 1910 in Baden-Baden.