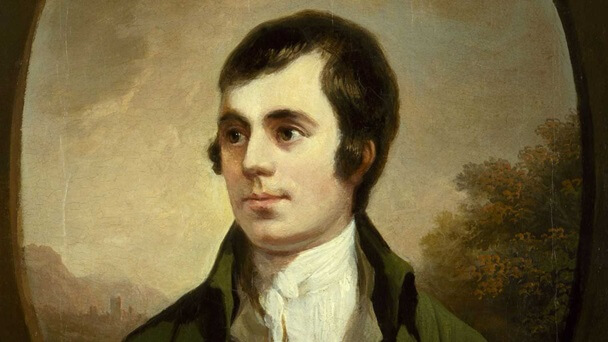

Who is Robert Burns? Detailed biography, life story of Robert Burns. Information on Robert Burns works, poems and philosophy.

Robert Burns; (1759-1796), Scottish poet, who was the most famous poet writing in the Scottish vernacular. However, today he is little read, and less understood. Even the Scots talk about him more than they study him. His greatest patriotic work, the Songs, is almost wholly neglected. Even among scholars he is frequently listed as a “preromantic” instead of what he was, the last great exemplar of Scottish vernacular poetry. A first-rate mind among second-raters, a traditional Scot in a day when his countrymen were aping the English, a liberal among Tories, a fiercely proud plebeian in a society based on family and rank, Burns was misunderstood when he was alive and is still misunderstood today.

Early Years:

He was born at Alloway, Ayrshire, on Jan. 25, 1759. He was the eldest of seven children of William Burnes—so the father spelled the name—a farmer, and Agnes Brown Burnes. (Robert changed the spelling of his name in 1786, when he published his first volume.)

A native of Kincardineshire, William Burnes had migrated to Edinburgh, and then to Ayr, where he leased land for a nursery. Described by his son as keenly understanding men and their ways, he was also by the same account a man of “stubborn, ungainly integrity, and headlong, ungovernable irascibility.” But his irascibility was not vented on his family; in his stern way Burnes was devoted to his wife and children. Largely self-educated, he hoped for better things for his sons. Agnes Burnes was illiterate, but her knowledge of folk literature and music contributed much to Robert’s education.

In 1765, Burnes joined with neighbors in employing John Murdoch as a teacher for their children. Two and a half years of Murdoch’s training thoroughly grounded the future poet in the elements of grammar. But Scottish vernacular literature was not studied in Scottish education; the gentry regarded their native speech as a relic of a semibarbarous past. The literature taught to Burns was the neoclassicism of Addison, Pope, and Dryden, with Shakespeare and Milton as the sole representatives of earlier periods, and with James Thomson as the standard Scottish poet of the 18th century.

Burns’ formal education was brief. In 1765 his father, unable to support his growing family on the 7 acres at Alloway, had rented, at inflated land prices, Mt. Oliphant farm, more than two miles from the school. Though the land at Mt. Oliphant was poor, Burnes lacked capital for anything better. As soon as his sons could work, their labor was needed, although the father managed to send Robert to school again for a few weeks at a time in 1772, 1773, and 1775. By the age of 13 the boy was doing a man’s work on inadequate food, which overstrained his heart and implanted the coronary disease that ultimately killed him.

In 1777, Burnes left Mt. Oliphant for Lochlea, between Mauchline and Tarbolton, again acquiring poor land at a high rental. However, the move brought Robert some social life. In 1779 he joined a dancing class (in “absolute defiance” of his father’s wishes), and in 1780 he helped organize a debating society, the Tarbolton Bachelors’ Club. After experimenting with raising flax at Lochlea, Robert went to Irvine in 1781 to learn flax dressing. Although nothing came of this venture except ill health, he did make the acquaintance there of Richard Brown, a sea captain, who praised his early verses and encouraged him to court the lassies.

At Lochlea things went from bad to worse for William Burnes. He became involved in litigation with his landlord, William M’Lure, who in turn was so in debt that his ownership of the land at Lochlea was doubtful. The legal struggle exhausted Burnes physically and financially. Although on Jan. 27, 1784, the Court of Session (supreme civil court of Scotland) decided in his favor, the strain had been too much, and he died on February 13. He left his affairs so encumbered that his family was saved from ruin only because, as employees on the farm, they were preferred creditors.

Mossgiel:

To keep the family together, Robert and his younger brother Gilbert rented Mossgiel farm from Gavin Hamilton, a prosperous Mauchline lawyer. The venture began with high hopes, but they were not fulfilled. Released from his father’s surveillance, Robert turned to new interests, amorous and poetical. As a result of the former, Elizabeth Paton, a servant at Mossgiel, bore him a daughter May 22, 1785. As a result of the latter, he established a local reputation.

The churches of the area were rent by quarrels between the Auld Licht (Old Light, or conservative) and New Licht (liberal) factions. Two ministers were squabbling over parish boundaries, the kirk session was prosecuting Gavin Hamilton for Sabbath-breaking. Burns satirized these affairs in such poems as The Twa Herds, The Holy Fair, and Holy Willie’s Prayer, which were circulated in manuscript form, delighting the liberals and infuriating the orthodox.

These poems, the first fruits of Burns’ mature genius, were the culmination of several years of literary self-education. As early as 1775, Burns had discovered the fashionable literature of sentiment embodied in the poetry of James Thomson and William Shenstone and in Henry Mackenzie’s mawkish novel, The Man of Feeling (1771). Early in 1783 he had begun a commonplace book, duly mottoed from Shenstone, in which he recorded some of his poems, as well as sententious comments on life and letters.

But his real awakening came in 1784, when he discovered the poems of his near-contempo-rary, Robert Fergusson. Here, for the first time, Burns learned that the Scots vernacular could still be a living force, that the speech his schoolmasters had shunned was capable of rich literary use. Instead of the tears of Mackenzie, Fergus-son presented a bold, racy interpretation of Burns’ own world, and the discovery caused him, he said, “to emulating vigor.” He directly imitated several poems from Fergusson— The Brigs of Ayr from The Plainstanes and the Causey, Halloween from The Daft Days, The Cotter’s Saturday Night from The Farmer’s Ingle—and in every instance except the last he improved upon the model in humor, freedom of movement, and the epigrammatic quality that makes Burns’ verse so quotable. By 1785 he had also found the verse-epistles of Allan Ramsay and William Hamilton of Gilbertfield. Again he used these poets as models, and again he improved upon the originals.

In short, the period from 1784 to 1786 was the most steadily productive of Burns’ life, although his lyric output had scarcely begun. Of the longer poems for which he is remembered— epistles, satires, descriptive pieces, and dramatic monologues—the greater part belong to these years. Tarn O’Shanter is the only major poem composed after 1786.

But Burns’ reckless conduct and his rebellion against the kirk now threatened an untimely end to his career. The birth of Elizabeth Paton’s daughter had brought him under kirk discipline. Later in 1785 he fell in love with Jean Armour, the daughter of a Mauchline contractor. By the beginning of 1786, Jean was pregnant, and Burns gave her a written acknowledgement of marriage. But her father would not have Burns for a son-in-law, and the “lines” were repudiated, less because of Burns’ morals than for his lack of worldly prospects.

This accumulation of troubles caused Burns to plan to emigrate to the island of Jamaica in the West Indies. First, however, he determined to publish his poems—not to earn passage money, but to leave a memorial behind. Negotiations for printing were already under way, and the poems, printed by John Wilson of Kilmarnock and sold by subscription, appeared on July 31, 1786. Within two weeks all 600 copies had been sold. Of the £40 profits, Betty Paton claimed half; the remaining money derived from the work, together with his share in Mossgiel, Burns signed over to his brother Gilbert, to forestall threatened legal action by James Armour.

During these same months Burns had a passing infatuation for still another young woman, Mary Campbell, the “Highland Mary” of his poetry. The details are obscure, but the notion that Mary was the great love of his life is a fantasy of romantic biographers.

In September 1786, Jean Armour bore twins. During the same month Burns abandoned his plans to go to the island of Jamaica. The Kilmarnock Poems had been read by influential gentry who urged the poet to try a larger subscription in Edinburgh. Chief among these advisers were Dugald Stewart, a professor of philosophy at Edinburgh University, and James Cunningham, Earl of Glencairn. In Edinburgh, the novelist Henry Mackenzie praised the poems, but he failed to discern the sound and intelligent reading out of which they had really grown and hailed Burns as a “Heaven-taught ploughman.”

Edinburgh:

Burns reached Edinburgh at the end of November 1786, and within a fortnight was the lion of the season. Though his reception would have turned most heads, he realized that the adulation sprang from novelty, and that the tide would soon ebb. Nor were all his patrons pleased with his conduct. Scottish society’ was highly class-conscious, and when its members condescended to receive a plowman, they expected gratitude for their condescension. But Burns, emotional and proud, maintained a bristling self-respect and spoke his mind more bluntly than was thought fitting for a plebeian.

The subscription for the Poems went well, however. To the publisher, William Creech, former tutor of Lord Glencairn, Burns sold his copyright for 100 guineas. The subscription itself netted about £500, of which the poet lent £180 to Gilbert. Creech, however, was dilatory in settling accounts, and Burns was forced to spend the next winter in Edinburgh to wind up his affairs.

Meanwhile, during the next few months after publication of the Poems, events of major importance occurred in Burns’ life. During May 1787 he toured the border with Robert Ainslie, a law student with whom he had formed a rather unfortunate intimacy. On returning to Mauchline, he found the Armours so dazzled by his success that they permitted a renewal of his relations with Jean, although he then had no thought of marriage. After returning to Edinburgh in August he went to the Highlands with William Nicol, a Latin teacher at Edinburgh High School. The tour was of poetic value in acquainting Burns with scenes famous in history and song, but it was a disaster socially because Nicol’s rudeness caused estrangement from at least two noble families—Atholl and Gordon—whose patronage might have been useful to Burns.

During the winter 1787-1788, in Edinburgh, Burns had a silly flirtation with Agnes M’Lehose, a grass widow of vaguely literary yearnings. Because an injured knee kept him housebound for several weeks, Burns conducted the affair mainly in letters full of unreal sentiment. His more basic amorous desires, not ministered to by “Clarinda” (as Mrs. M’Lehose styled herself, from the Spectator, .with Burns reciprocating as “Sylvander”), were satisfied by a servant lass, Jenny Clow, as in the previous winter they had been satisfied by a certain Meg Cameron. Since Jenny and Meg both bore him children, these liaisons did nothing to lessen Edinburgh gossip. And the Clarinda affair had little relation to the realities of Burns’ life. Reality was better served in April 1788, when Bums formally acknowledged Jean Armour as his wife, a few weeks after she again bore him twins, who did not live.

Considering possible futures, Burns decided that the excise service, which collected excise taxes, offered the best assurance of a livelihood. However, his patrons disapproved of his entering this profession. Burns, they believed, was a Heaven-taught plowman and should continue as such. Among these patrons was Patrick Miller, owner of the Dalswinton estate, near Dumfries. At Miller’s urging, Burns, against his own better judgment, leased the Ellisland farm in June 1788, on terms that might have been favorable if the soil had not been depleted and if the farm had had proper buildings. For nearly a year Burns had no house of his own.

“Museum” Songs:

About this time, Burns became deeply involved in a literary project with an Edinburgh acquaintance, James Johnson. Johnson was a music engraver, imperfectly educated but deeply devoted to the traditional songs of Scotland. In 1787, shortly before meeting Burns, Johnson had prepared the first volume of The Scots Musical Museum, in which he proposed to collect all the extant traditional Scots songs with printable words. Burns became so fired by the project that he took over as its editor. Originally planned for two volumes of 100 songs each, the Museum, under Burns’ guidance, grew to six volumes, of which the last was not published until 1803.

The poet’s contributions ranged from collecting folk melodies with traditional words to composing wholly new verses, some to airs that lacked printable words, others to previously wordless dance tunes. Between these extremes, Burns did everything from making minor emendations to fitting new words to old fragments of stanza or chorus. (For his cronies, he also preserved, and sometimes embellished, the bawdy old words that could not be printed.) For the Museum and for George Thomson’s Select Collection (1793-1841), to which he began contributing in 1792, Burns wrote more than 300 lyrics, all composed to specific airs.

Neglected though most of these lyrics are today, their importance to Burns personally cannot be overstated. Without this means of expression, his poetic impulse might have been crushed at Ellisland. The farm, as he had feared, was a losing proposition. Fortunately, however, he knew Dr. Alexander Wood, whom he had met when his knee was injured in Edinburgh. On hearing that Burns still hoped for an excise commission, Wood did what more highly placed patrons had refused to do; he obtained, from Robert Graham of Fintry, chief commissioner of excise, the warrant for Burns to train for the service.

By the summer of 1789 it was obvious that Ellisland could not support a growing family. Burns applied for and received an appointment as rural surveyor in the district to which his farm belonged. Somewhat to the surprise of his superiors, he proved to be an able and conscientious officer. The work, requiring that Burns ride 200 miles a week in all weathers, was hard on his health, and harder on his poetry. Yet, thanks to the Museum project, he was able to compose songs as he rode, humming the airs until he was familiar with them, and then finding words to express the spirit of the music.

Dumfries:

In 1790, Burns was transferred to duty in Dumfries, and in November 1791 he finally gave up Ellisland. Thenceforth he depended wholly on his excise salary for a livelihood. His songs vyere a patriotic service for which he refused money, and in 1793 he even permitted Creech to publish an augmented edition of the Poems without additional payment. Chief of the new poems in this second edition was Tam O’Shanter, composed in 1790, after the poet had met Francis Grose, who was studying the antiquities of Scotland. Burns had suggested the ruins of Alloway Kirk as a subject for an engraving in Grose’s forthcoming book. Grose agreed, on condition that Burns supply a witch story to accompany the picture. Burns’ single greatest poem was thus written by chance.

Traditionally, the Dumfries years have been called a period of moral and physical decline. The latter was partly true, as Burns’ heart ailment worsened, but available evidence offers little confirmation of the former. He continued to fulfill his excise duties and continued writing songs, and he left no debts to indicate heavy dissipation. But he was, as always, reckless in speech, and at the outbreak of the French Revolution his strong radical sympathies caused him trouble more than once. That his superiors thought well of him seems proved by the fact that when Burns was charged with having made seditious utterances, Collector William Corbet investigated in person and exonerated the poet.

Though cleared of charges, Burns was shaken by the ordeal. In addition, he became estranged from several of the gentry, some of whom were angered by his opinions, while others disapproved of his unseemly conduct, perhaps instigated by people who wished him no good. Nevertheless, Burns’ professional reputation remained sound. In 1793 he was granted burgess privileges in the Dumfries schools. Earlier, he had been named eligible for promotion to supervisor of excise, and for several months in 1795 he served in that capacity while his chief was ill.

Late in 1795, Burns’ health began to fail, and for two months during that winter he was ill with rheumatic fever. He partially recovered during the spring, but thereafter his decline was steady, and on July 21, 1796, he died in Dumfries of heart disease.

A subscription was organized to provide for the maintenance of Burns’ widow and the education of his children, seven of whom survived him. Unfortunately, the preparation of the memorial edition of Burns’ works was entrusted to Dr. James Currie of Liverpool, a conservative in religion and politics, and a teetotaler, who had never met the poet. Currie’s biography, therefore, served to perpetuate a distorted view of the poet’s character—a view that was partly dispelled in the 20th century by the recovery of the complete text of Burns’ letters.