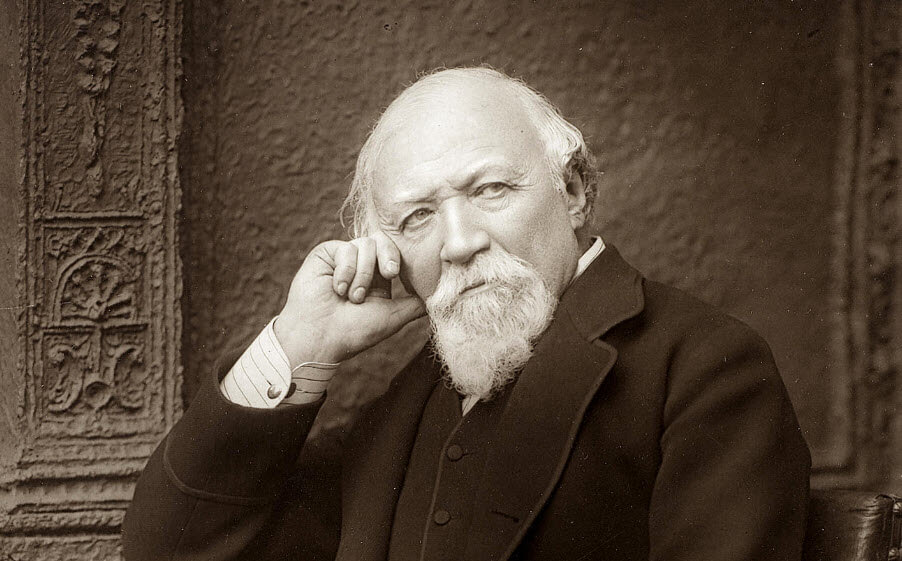

Who was Robert Browning? Information on English poet Robert Browning biography, life story, poems and works.

Robert Browning; (1812-1889), English poet, who grew to maturity during the decline of romanticism, when personal poetic vision was giving way to a concern for social fcnd religious values in an increasingly pluralistic society. Popular recognition was long denied him, but to the later Victorians, who idolized him, he represented an unorthodox, basically optimistic Christianity, as he confronted what many regarded as spiritually destructive tendeneies in contemporary thought. His experimental style and development of the dramatic monologue may be his most lasting eontributions to poetry.

Early life

Browning was born in the London suburb of Camberwell on May 7, 1812. He grew up in a permissive home atmosphere that encouraged his natural independence of mind. His father was an amateur scholar and book collector, whose tutoring and library of rare volumes provided most of the boy’s early education. His Scottish mother, a devout Congregationalist, had a decisive religious influence on her son and nurtured his devotion to music, flowers, and animals.

For a few years Browning attended a public school in Peckham, which he disliked, and when he left at the age of 14, his somewhat aggressive nature was stili intact. For a while he was tutored in music and languages, and he studied briefly at the University of London.

Source: wikipedia.org

Browning decided on a poetic career when he was 17. In 1833 he published Pauline, a poem that reveals a strong debt to Shelley. Pauline was not well received. John Stuart Mili wrote that its author possessed a “morbid self-consciousness,” an assessment which so alarmed Browning that he determined to avoid incautious self-exposure and to write a more objective form of poetry. Thereafter he submerged his private feelings in dramatic portraits—an impulse that seems to have returned him to an earlier, more genuine instinct.

Browning’s next volume, Paracelsus (1835), was not a popular success, but through it he became acquainted with such men as the poets Wordsworth and Landor and the actor William Macready. At Macready’s request, Browning wrote the drama Strafford, which was acted in 1837. Thus began the poet’s 10-year flirtation with the drama. Only two more of his plays reached the stage: A Blot in the ‘Scutcheon (1843) and Colombe’s Birthday (1844; acted in 1853). Macready declined to produce King Victor and King Charles (1842) and The Return of the Druses (1843), and Browning did not offer Luria and A Soul’s Tragedy (both 1846) for the stage. Although Browning’s plays were not entirely successful, they enabled him to work out dramatic techniques that he later employed brilliantly in his monologues.

The publication of Sordello (1840), a difficult poem that readers found unintelligible, earned Browning the reputation for “obscurity” which he was never entirely able to dispel. In order to popularize his work, he published a series of eight pamphlets between 1841 and 1846, collectively entitled Belh and Pomegranates. The series began with Pippa Passes, and four other pamphlets were devoted to the plays mentioned above. The third pamphlet, Dramatic Lyrics (1842), and the seventh, Dramatic Romances and Lyrics (1845), include some of Browning’s best-known poems, such as My Last Duchess, Soliloquy in a Spanish Cloister, Home Thoughts from Abroad, and The Bishop Orders His Tomb.

Middle Years

In 1845, Browning met the poet Elizabeth Barrett (see Browning, Elizabeth Barrett ). Because her father opposed their marriage, they were secretly wed in 1846. They traveled first to France and then to Italy, and lived in Florence until Elizabeth’s death in 1861.

In 1850, Browning published Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day, his first poetic religious affirmation. This was followed by Men and Women (1855), which included Fra Lippo Lippi, Andrea del Sarto, Memorabilia, and Cleon, and by Dramatis Personae (1864). The first did not succeed with the public, but the second found a large readership.

In the 1860’s Browning became fully absorbed in the Old Yellow Book, which he had found at a bookstore in Florence. The book, a record of a 17th century murder trial, was an unlikely source for a summary poetic achievement. However, its subject matter provided Browning with the basis for The Ring and the Book (1868-1869), his magnum opus, in which he articulated his mature religious and artistic convictions. With this work, Browning became an eminent Victorian poet.

Later Life

From 1868, Browning fully and consciously enjoyed the rewards of his newly won popularity. A brilliant conversationalist, he was welcomed into society. Several universities honored him, and he was increasingly venerated as a great spiritual teacher. He was, however, always reluctant to talk about himself or his poetry, and he avoided public speaking.

During these years, Browning’s poetic output, often in his happiest vein, was prolific. However, in some of the poems he tended to indulge in doubtful metaphysical discourse. His later works include Balaustion’s Adventure (1871), Prince Hohemtiel-Schwangau (1871), Fifine at the Fair (1872), Red Cotton Night-Cap Country (1873), and La Saisiaz (1878). Two series of Dramatic Idyls, containing some of his best later poetry, were published in 1879 and 1880. Jocoseria (1883) and Ferishtah’s Fancies (1884) are collections of shorter poems. Parleyings with Certain Teople of Importance in Their Day, an autobiographical poem important for tracing Browning’s early development, appeared in 1887. Asolando, with its famous Epilogue, was published on the day of his death. He died on Dec. 12, 1889, in Venice.

Assessment

Browning’s once secure reputation as a great thinker did not fully survive later attacks, chiefly those in the 20th century. In his poetry, he was nevertheless capable of intense introspective subtlety and vigorous analysis of human motives. His charaeters, especially those caught in spontaneous self-justification, are often bewilderingly complex.

Browning believed that art is rooted in man’s ethical nature, and his concern is therefore ultimately a moral one. He stressed the importance of inteliect in moral affairs, but he deeply distrusted speculative thought divorced from the process of life. His men and women cannot be judged merely by their acts, but by their quality of character fashioned in the act of living. A genuine moral instinct may even justify suspension of the normal social ethic.

Browning brought religious beliefs to the test of experienoe, discarding such orthodox dogmas as original sin and the atonement. Basic to his beliefs was the Incarnation of Christ, which he viewed as a revelation of divine love, necessary to guide and to justify human love. Much of his poetry explores the meaning of that doctrine as it applies to human experience. The poet, he thought, apprehends such matters’more keenly than others, and by conveying the truth through poetry he partakes of the divine mission of Christ, however imperfectly. According to Browning, doubt is merely a requirement of the moral struggle. Man must continually reassert his beliefs and his moral identity, but he is assured of ultimate success if he obeys his reason and his moral instincts, provided both are informed by love. Although this optimism has been called facile (and some of Browning’s poems appear to support that judgment), his hopefulness is based on subtle psyohological and religious insight. Browning’s philosophy of engagement in life, even in the face of apparent failure, has been persistently appealing.

mavi