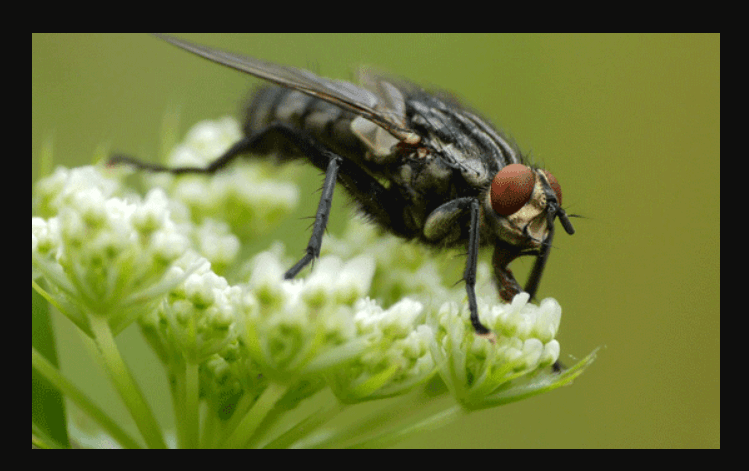

How do flies pollinate? Which flowers flies pollinate? Discover the fascinating world of fly-mediated pollination in our enlightening video. Gain insights into the unique techniques and mechanisms by which flies contribute to the essential process of pollination.

Pollination by Flies

The many different kinds of flies which feed on flowers may be conveniently divided into two classes, the long-tongued flies and the short-tongued flies. The first class include the syrphus flies, Bombyliidae, and certain others. These insects live on the nectar of flowers and are well adapted in their bodily structures, habits, and sensory perceptions for securing it. Much of what has already been said regarding bees is equally true of syrphid and bombylid flies, and the types of flowers which attract bees also attract the specialized flower-visiting flies.

The class of short-tongued flies is a numerous and miscellaneous lot, consisting of some thirty or more families. The diverse members of this group all possess one characteristic in common, however, namely the absence of any marked morphological or psychological specializations for feeding on flowers. Most of them probably derive most of their nourishment from other sources, particularly carrion, dung, humus, sap, and blood, and hence are only occasional visitors of flowers. Their performance on flowers may be described in the phraseology of human affairs as unindus-trious, unskilled and stupid. Unlike bees, moths and long-tongued flies, they are attracted to flowers not by vision but by their sense of smell, as has been shown experimentally. The odors which attract them, moreover, are the odors of carrion, dung, fish, and similar products of decay.

Fly flowers give off just these odors. The flowers of Rafflesia smell like putrefying flesh; those of black arum (Arum nigrum) like human dung; those of the lily Scoliopus bigelovii like fish oil; one kind of Dutchman’s-pipe (Aristolo-chia gigas) smells like decaying tobacco, while another kind (Aristoiochia californica) smells like humus. The colors of fly flowers are dull. Some are dark red, purple or brown; others are white or greenish-yellow.

Some fly flowers, exemplified by false hellebore (Veratrum) and the saxifrages, provide nectar in a shallow basin where it can be lapped up by the various short-tongued visitors. Other fly flowers secure the pollen-carrying services of flies without expending any nectar on them. In this case the flies are attracted tc special glistening streaks, spots, or bodies, as in the saxifrage Parnassia, the lily Parts, and the orchid Ophrys. Still other fly flowers, such as Dutchman’s-pipe and arum not only fail to feed the flies, but actually imprison them for a day or twc in a floral trap while they are being doused with pollen. After their release from the first flower, some of the flies get into a second trap, where they have the opportunity during another day or two to pollinate the stigmas thoroughly and to acquire a fresh load of pollen.

The American floral ecologist John Harvey Lovell (1860-1939) once remarked upon the vast difference in the reception accorded by flowers to bees and to flies. The efficient and constant bees are offered nectar, pollen, shelter, a landing platform, bright colors, and sweet odors, and their competitors for the limited supply of food are excluded from the floral chamber. For the stupid flies, on the other hand, there are pitfalls, prisons, pinchtraps, and deceptive nectaries.