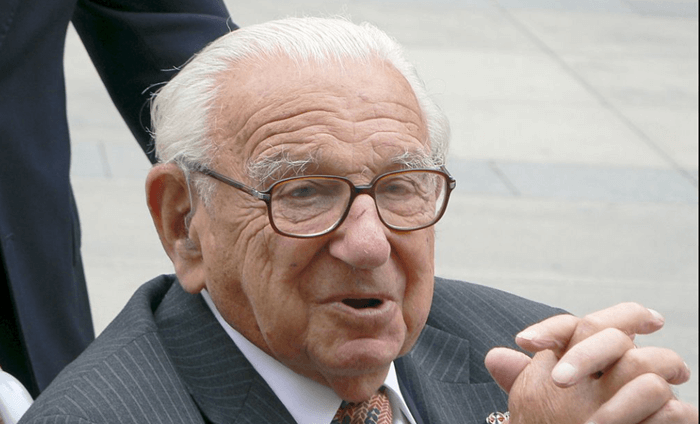

Nicholas Winton (Hampstead, London, May 19, 1909-Slough, Berkshire, July 1, 2015) was a British philanthropist of Jewish origin who saved 669 Jewish children from death at the hands of Nazi Germany just before the start of World War II in 1939.

Within the episode called Kindertransport. He lived in Maidenhead, a small town in the south of England, until July 1, 2015, when he died at the age of 106 at Wexham Hospital in Slough, England.

Nicholas Winton

Biography

He was the son of Rudolph Wertheim, bank manager, and Barbara Wertheimer, both German Jews who migrated to London two years ago.The family name was Wertheim, but was changed to Winton as part of their interest in joining. They also converted to Christianity, and Winton was baptized.His childhood and adolescence passed smoothly and calmly, as befits a young Englishman from a wealthy family of the turn of the century.

In 1931, after completing his studies, he went to work as a stockbroker in his hometown, until the outbreak of World War II. In December 1938, he was planning to spend a few days skiing in Switzerland, when he received a phone call from his friend Martin Blake, in which he asked him to cancel all the plans he had for those days and to go to Prague. “I have a very interesting proposition for you. Don’t bother bringing skis,” Blake told him. Upon arrival in Prague, Blake asked if he wanted to lend a hand and work temporarily in the area’s refugee camps, where thousands of human beings, many of whom were children of Hebrew origin, were living in subhuman conditions. The vision of the drama deeply affected him. He decided to set up a makeshift office in the hotel room where he was staying and began to develop a plan to get as many Jewish children out of the country as possible to take them to other countries and save their lives.

Before long, the Jewish community in the Czech capital echoed Winton’s presence in the city and the motive that prompted him to continue there. Hence, hundreds of families came to visit him to try to persuade him to include their children in the list of children he was going to try to save. The avalanche of requests caused him to be forced to open a new office on Vorsilska Street in order to serve as many people as possible. His friend Trevor Chadwick personally handled that office. In a few days, hundreds of families had come to him to ask for help to save their children.

Aware of the magnitude of the problem before him, he contacted the ambassadors of nations that he believed could take care of the children, but only the Swedish government agreed to deal with a group of children. For its part, Great Britain promised to accept those under the age of 18 but only if it found families willing to take them in before, and who should also agree to pay in advance a deposit of £ 50 for each child to pay for their future return home.

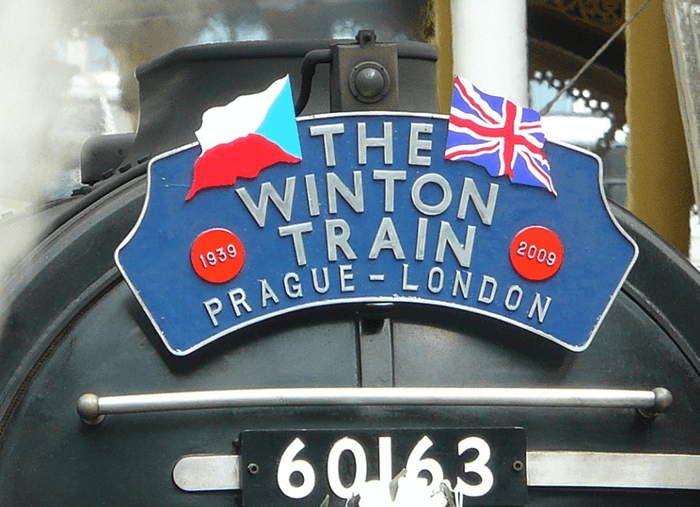

The Winton Train

Eventually Winton had to return to London to return to his job. His return did not prevent him from continuing to shore up his rescue plan; Thus, he created an organization that he named The British Committee for Czechoslovak Refugees, Children’s Section, which initially only had himself, his mother, his secretary and a few volunteers.

Once the Committee was created, Winton had to face a big problem: getting the necessary financing to pay the costs of the children’s train journey from Czechoslovakia to the host country and finding people who would accept to take care of these children and pay the £ 50 that the government claimed. Winton began running advertisements in British newspapers, in churches, and in synagogues asking for help. Londoners’ response was enthusiastic. In a few weeks, hundreds of families agreed to welcome the children and provided the money necessary to start the transport from Czechoslovakia to the English capital.

The first of these was carried out on March 14, 1939 by plane.

In the following months, another seven transports were organized, all by train. The last one took place on August 2. The railroads were destined for Liverpool Street station, in London, where the host families were waiting.

The eighth train had to leave Prague on September 1, 1939 and another 250 children were going to travel on it, but that same day Germany invaded Poland and closed the borders. The transportation literally disappeared. None of the minors was ever seen again. There were 250 victims who joined the more than 15,000 children who were killed in Czechoslovakia during World War II.

Winton rescued a total of 669 Jewish children. His feat, which would have deserved multiple decorations and acts of tribute, was forgotten for 50 years, since he preferred to keep what happened secret. It was not until 1988 when Greta, his wife, found an old leather briefcase hidden in the attic of the house and, rummaging through the papers it contained, came across the photos of 669 children, a list with the name of all of them and some letters from his parents. Such discovery caused that Winton had no choice but to explain to his wife what had happened decades ago.

Shocked by the story her husband had just told her, Greta contacted Elisabeth Maxwell, a historian specialized in the Nazi Holocaust and the wife of communication magnate Robert Maxwell, owner of newspapers such as the Daily Mirror and the Sunday Mirror.

Maxwell, whose roots were Czech, was so impressed by Winton’s deed that he decided to publish the story in his diaries. Shortly thereafter, the BBC echoed events that had occurred half a century earlier, and events rushed. In a few days he went from being an anonymous character to becoming a national hero, both in his country and in the former Czechoslovakia. Thus, in 1993 Queen Elizabeth II appointed him a Member of the British Empire, years later, on December 31, 2002, he was awarded the title of Knight for his services to Humanity; he also holds the title of Liberator of the City of Prague and the Order of T. G. Marsaryk, which he received from Vaclav Havel on October 28, 1998; on October 9, 2007 he was awarded the highest Czech military decoration, the 1st Class Cross, in a ceremony in which the Czech ambassador showed his public support for an initiative promoted by students from the country, which already had more than 32 000 signatures and asking for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 2010, the British Government also awarded him the Holocaust Hero medal, and his figure is expected to be prominently recognized in a permanent monument preparing to commemorate the tragedy of the Second World War. His last decoration was in 2014, in which Winton received the Order of the White Lion in Prague.

At the cinema

The story of Nicholas Winton has been the inspiration for the making of two films: All My Loved Ones (1999), directed by Czech filmmaker Matej Mináč, and Nicholas Winton: (The Power of Good: Nicholas Winton), a documentary that won an Emmy in 2002.