What is Lutheranism about? When was Lutheranism founded? Information on the beliefs, facts and origins of Lutheranism.

LUTHERANISM is the Christian movement initiated by Martin Luther (1483-1546) in his controversy with the Roman Catholic Church of his day. One of the few major Protestant forces to be named after its founder, this oldest and largest of the Protestant clusters cannot be understood without some reference to the activities and attitudes of its founder.

THE FOUNDER

Luther, an Augustinian friar, experienced spiritual travail in a monastery. He became ever more conscious of the wrath of God and ever more anxious about his failures to appease an angry God through his own faithful devotion to monastic routine or his attempts at effecting “good works” that would be pleasing to God. Lutheranism preserves Luther’s concern for the spiritual struggle over human sin and failure, and his own subsequent rejection of the path of merit, or works, as a means of coming to peace with God.

Between 1513 and 1517, particularly through his study of St. Paul’s letters in the New Testament, Luther came to recognize divine grace and liberation in deeply personal ways. His reverence for the Scriptures, which had been the means of his recognition of divine grace, and his awareness of the importance of the forgiveness of sins, representing the center of his experience, remained as keystones in later Lutheranism.

Increasingly emboldened by his discoveries, Luther began to attack Catholic practices that he believed kept both scriptural teaching and the experience of Christian freedom from the faithful. This approach led to a direct confrontation with both religious and imperial authorities, and in 1520 he was excommunicated. Yet he continued to have a high regard for many of the teachings that he saw as buried but still present in Catholicism. Lutheranism has continued to be ambivalent about Roman Catholicism.

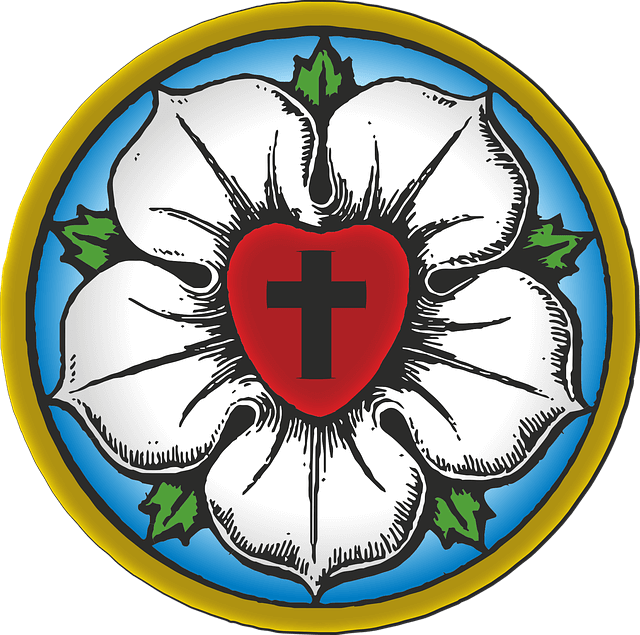

Source : pixabay.com

The Lutheran movement was contemporary with other reforms, particularly those of John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli in Switzerland, France, and the Low Countries; of the Anglicans in England; and of the Anabaptists and radical reformers all over northern Europe. Luther was basically unfriendly to these movements, exaggerating his differences with them in order to protect “his Gospel” from what he saw to be dilution, distortion, or compromise. Yet he regarded other reformers as allies of a kind against the pope and the emperor. Subsequent Lutheranism has often shown some of his ambivalence on this subject. At times it has been denunciatory of Anglicanism and Reformed and Anabaptist Protestantism. Just as often, it has been able to side with other Protestants defensively against Catholicism or, more positively, in cultural-political causes and in work for Christian reunion.

Finally, Luther’s reforming spark caught on at a time when northern European territories were showing signs of independence from Mediterranean powers, and when a new nationalism was coming to birth. Whether Lutheranism could have survived only as a spiritual, intellectual, or theological revolt cannot be answered. It is clear that the movement did survive with the tremendous impetus given it by German and Scandinavian civil powers, by princes who found Lutheran Christianity profitable, and by the people, who found it attractive. Ever since, Lutheranism has tended to be at ease with “the powers that be” in the nations where it has found a home.

LUTHERAN TEACHINGS

There is little difficulty in making generalizations about official Lutheran teaching, since it has been elaborated in the Book of Concord. That collection includes two extremely influential catechisms of Luther: a Small Catechism, through which countless Lutheran children have been instructed; and a Greater Catechism, which has shaped the teaching of generations of pastors and leaders. There may be controversies over niceties, but the major points of doctrine are clearer among Lutherans than in most Protestant groups.

At the center is the teaching usually called “justification by faith” or, better, “justification by grace through faith.” The quest for comprehension of this teaching again leads back to Luther’s own experience. Man is not seen to be justified before God through his own efforts to be good or to be religious or to be pious. He meets enemies—sin, death, the devil, and even the wrath of God—against which he, as a “spiritual heir of Adam,” is powerless. God’s Law is not a rule for living; instead it comes at him as an accuser and tyrant, driving him to the mercies of God.

Here God’s activity in Jesus Christ’s sacrifice of himself on the cross and his subsequent Resurrection is determinative. The Father accepts this sacrifice and justifies those who by faith accept the gift of grace, which identifies them with him. Justification, then, does not represent continuities between “the old Adam” and “the new man in Christ,” but instead suggests a breach, followed by an act of new creation. Man in Christ is forgiven and freed for eternal life with God and for works of spontaneous love toward his fellowmen, toward whom he is now to show himself “another Christ.”

From this center, or heart, all the other Lutheran teachings flow. The Bible is not a code book of laws and rules, but—once the Law contained in it has done its work—it is the book of the Gospel, the Good News of what God does for man.

The Bible is the church’s book, heard and read in the context of a community. Luther never tired of depicting the church as a congregation or a family that first brings a man to Christ through baptism and then nurtures him in the Bible. Later Lutheranism has sometimes turned individualist, asking people to accept. Jesus Christ as their personal Saviour, for the most part Lutheranism has been churchly and not sectarian or individualistic. As such, it has accented the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Sacraments are usually defined as sacred acts that impart grace, are established by God, are instituted by Jesus Christ, and combine the divine word and visible elements.

Baptism is not a mere symbolic washing; it actually affects change in the form of forgiveness of sins and deliverance from the power of evil. It promises the gift of eternal life. Infant baptism is practiced, and any form of applying the water is permissible. The Christian is pictured as “returning to his baptism” in every act of repentance, in which “the new man in Christ” was and is put on afresh.

The Lord’s Supper, or Holy Communion (the Eucharist), is an expression of life in the church, which one has entered through baptism. Lutherans receive both bread and wine, believing that “in, with, and under” these visible elements Christ’s body and blood are present again to work forgiveness in people. Their view of the Lord’s Supper conflicted with the Catholic teaching, which held that the substance of the elements was invisibly but actually changed to Christ’s body and blood. It also differed from the views of many other Protestants, who often saw in the bread and wine mere symbols or representations of Christ’s body and blood.

In most respects, Lutherans’ support of the ancient ecumenical councils and acceptance of the ancient creedal formulations have led to their being regarded as simply exponents of classic doctrines like the Trinity and of Jesus Christ as truly divine and truly human. They have not tried to innovate while accepting these and have seldom been accused of adapting or distorting such historic doctrines.

Still, there are special ways in which these teachings have been taken over by Lutherans. They have, in contrast to Catholic and Reformed teachers, tried to keep the message of the Law and the Gospel distinct, not blending them, as it appears to them others do. Blending, they feel, leads to a sentimentalization of the moral life on one hand, or legalism in the spiritual life, on the other. Again, contrary to the Reformed, their theologians have argued that finitum capax in-finiti, the finite, is capable of bearing the infinite. This approach has helped them retain their views of the sacramental elements as actual bearers, and not merely symbols, of a divine presence. Third, Lutheran theology is typically a “theology of the cross” as opposed to a “theology of glory ; that is, it stresses the historical reality of the life of Jesus as opposed to a stress on abstract discussions of the natures of Christ, his second coming, and the like. This approach tends to downgrade speculation about deity, to devalue abstract metaphysical concerns, and to accent the historical revelation of God in Christ and the church.

Lutheran Ethics.

In ethics and morals the Law is sometimes pictured as a curb against gross sins and a mirror for self-scrutiny, but only rarely as a rule of life. Instead, for the Christian, the new life in Christ commits him to works of love in response to his neighbor’s need and in the path of Christ. Lutheran ethics tries to keep alive the paradox of Luther’s famous formulation: “A Christian is a perfectly free lord of all, subject to none. A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all.” Freedom is central to such a definition, and it is best described as a freedom inaugurated by God and so extensive that man no longer has to worry about his relation with God—and hence is free to have regard for his neighbor.

From this point of view, Lutherans may be seen to propose something like an ethics of “situation” or “context.” Informed by principles of conduct, philosophical inquiry, or local custom, the Christian may go a long way toward anticipating answers in moral settings. But under extreme circumstances all these can, both in theory and in practice, be bracketed or canceled when acts of love commit the Christian to serve his neighbor. In the spirit of Christ’s saying, “The sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath,” regard for the man in need is central. Often quoted is Luther’s statement, “when the law impels one against love, it ceases and should no longer be a law; but where no obstacle is in the way, the keeping of the law is proof of love, which lies hidden in the heart. Therefore you need of the law, that love may be manifested; but if it cannot be kept without injury to the neighbor, God wants us to suspend and ignore the law.”

Source : pixabay.com

Of course, this approach often leaves the debate approximately where it began: How is one certain just what is the loving act toward one’s neighbor? And what if the needs of neighbors conflict? For example, Lutheranism has usually permitted the bearing of arms in a “just war,” in support of “order” and to show a kind of love to those defended—but this is hardly expressive of direct love to the one who is to be killed on the other side. Here it is clear that Lutheranism does not foresee perfectionism in ethics, but throws man into a world of conflict and choices between two apparent evils. There will, therefore, be failure in the moral life even on the part of the best intentioned, and they will need forgiveness and new freedom for subsequent activities.

Whatever else may be said, Lutheran teaching cannot be accused of being casual about the seriousness of God’s Law on one hand, or limiting the freedom of the forgiven man to act, in surprising ways, on the other.

Church Order.

In the realm of church order, it is difficult to state a Lutheran position because there has been such a variety of practices. Many church bodies accent “order” as much as they do “faith,” but Lutherans definitely concentrate on the latter. This is not to say that they are unconcerned with questions of polity and governance, but only that they rarely regard one form as divinely prescribed. Inevitably, many of them have found biblical warrant for forms that they inherited or that they transformed for reasons of practical expediency; but their inheritances and improvisations have been too varied to permit them even the luxury of seeking uniformity.

Lutherans want to see themselves as steering a middle road between an authoritarianism based on a single prescribed polity and an anarchy resulting from unconcern or mere contention. “Let all things be done decently and in order” (I Corinthians 14:40) is a frequently quoted scriptural passage. The transition from Roman Catholicism to Protestantism was so smooth in Sweden that the Church of Sweden was able to retain episcopacy as being of the essence of the church, with full claims to the apostolic succession. Thus that form of Lutheranism is in fellowship with the Anglican Communion, which holds similar views. But the Church of Sweden is also at home with the German Lutherans, most of whom do have bishops, but only as a practical benefit to the churches.

In the United States the Scandinavians and Germans abandoned the idea of episcopacy, though their district and synodical presidents usually have quasi-episcopal powers. In America, the congregation is the most important unit of jurisdiction, and occasional extravagant claims of a New Testament warrant for such a polity are advanced. But pure Congregationalism is compromised in North America by the powers that are possessed by denominational bureaus and boards, or inter congregational agencies, zones, circuits, or “synods.” An informal coinage, “presbygationalism,” is sometimes used to describe the American result.

If polity is ill defined, so are clergy-lay relations. The first generation of Lutherans spoke of “the priesthood of all believers,” and this phrase is sometimes invoked to describe the high status given the laymen.

In practice, however, the Lutherans failed to complete the definition of lay roles in the church, and there have been many improvisations through the years. The Augsburg Confession said that only those who were “properly called” should preach and engage in public ministry of the sacraments, without spelling out who could be properly called. The phrase gradually came to be applied to specially trained men, the equivalent of seminary graduates, who have been set aside for the act of preaching. As a result, the layman did often take on what amounted to a lesser role or at least a circumscribed one.

The minister, as a result, has often been set aside for special regard. He is to be the resident expert on the Word of God. Usually he is called “pastor,” to stress his part in the care of souls. He has been less likely to involve himself with public affairs than many of his non-Lutheran counterparts. Until the middle of the 20th century the ordination of women was almost everywhere proscribed, but thereafter, beginning in Europe, advocacy of the practice has spread. In the United States two of the three main Lutheran bodies (the American Lutheran Church and the Lutheran Church in America) authorize the ordination of qualified women. Women have long been called to be nurses, teachers, missionaries, and deaconesses in the service of the church, but many Lutherans tended to confine women to their older cultural role in Germany: Kinder, Kirche, Küche—children, church, kitchen.

Worship.

So far as worship is concerned, Lutheranism tolerates and encourages a variety of practices. Luther himself pointed to two directions when he provided a more conservative and ceremonial Formula Missae and an informal and popular vernacular Deutsche Messe, or “German Mass.” The sacrament of the Lord’s Supper is frequently celebrated, but not necessarily weekly. In sacramental and other services, the preached Word is a highlight: Lutherans put great stress on the ability to prepare and deliver a sermon in training and evaluating ministers, and a good sermon is one of the chief things the laity expect at worship.

Sacraments and preaching are surrounded by hymn singing, prayer, and readings from the Old Testament. The New Testament readings are called “The Epistle,” which ordinarily is drawn from one of the New Testament letters, and “The Gospel,” which is drawn from one of the four Gospels. Services usually follow the framework of the Roman Catholic Mass of Luther’s time, with elements like the Introit, the Gradual, the Collect, the Creed, the Sanctus, the Agnus Dei, and other ancient and familiar readings and chants. The minister is usually vested, sometimes in the black academic robe that Luther chose for his services of preaching, sometimes in the combination of cassock, surplice, and stole that became popular in America, and sometimes in the full historic eucharistic vestments, including the chasuble. While the services of worship may vary from the equivalent of tent revivalism to the High Mass with incense, Lutheran worship through the centuries can be characterized by terms implying simplicity and seriousness.

While the Lutheran Confessions of the 16th century at one point speak of penance as a sacrament, it is not usually thought of in that category. Yet confession of sins on the private level is an option, and public or corporate confession of sins almost always precedes the reception of the Lord’s Supper.

Use of 20th Century Techniques.

In the 20th century, without necessarily parting with their doctrinal and confessional conservatism, Lutherans have shown a new openness to adapting to cultural change and to exploiting technical innovations. As one example, they have pioneered in the religious use of mass communications, producing films and radio and television programs with uncommon enthusiasm and frequent expertise. In the United States they have taken advantage of new approaches to stewardship for the support of their congregations and causes. Yet these have been external adaptations and do not always represent accompanying ideological or doctrinal innovations. If one thing has typified Lutheranism in the ecumenical spectrum, it has been its serious regard for the teachings that related to Martin Luther’s original personal experience, teachings that were defined in creeds and confessions of the 16th century.

LUTHERANISM IN THE WORLD

Spread of Lutheranism.

While the Lutheran movement was born in Saxony, and specifically in the then-new university town of Wittenberg, it spread rapidly into many parts of Germany. In general, Lutheranism found most ready acceptance as it moved north and east. Germany was then nothing but a loose grouping of scores of rather autonomous principalities. To the southeast, as in Bavaria, Catholicism remained predominant; to the southwest the Calvinist and Zwinglian reforms were more aggressive. In general, the Lutheran movement was therefore destined to be strongest and to live most of its years in the far north of the Continent.

To the south and west Luther’s co-workers met almost total frustration. They were hardly ever able to penetrate Italy, Spain, or Portugal at all. From the 16th to the 20th century, Lutheranism and other forms of Protestantism have remained at best tiny and often sheltered enclaves there, experiencing persecution, or at best tolerance. They have left virtually no cultural stamp on the Mediterranean nations.

Source : pixabay.com

Nor did Lutheranism ever successfully cross the Channel to England. A number of Lutherans played roles as intellectuals in Henry VIII’s era of Anglican reform. Western Europe in the mid-16th century did house an almost ecumenical intellectual elite community that resulted from persecution and exile. Some Englishmen were among this group and other members of it exerted influences on English religious life. But Henry VIII was anti-Lutheran, and his political and ecclesiastical followers went routes largely independent of Luther. In the 20th century Lutherans remained a tiny minority in the British Isles.

While Lutheranism was somewhat more successful in the Low Countries, the Reformed churches formed a kind of arc beginning in the Netherlands, and stretching down through France. Lutherans have become reasonably strong only in Alsace-Lorraine, while in Switzerland they have known only enclave existence. Lutherans did move east, into Czechoslovakia, Rumania, Yugoslavia, Poland, and Russia, where they were surrounded by both Roman Catholics and Easttern Orthodox Christians. Their once-significant numbers there have declined greatly in the 20th century, particularly in the face of Communist attitudes critical of religion and the inconveniences and occasional persecutions that religious groups have suffered in Communist countries.

Outside Germany, then, the only place where Lutherans came to prevail was in Scandinavia. As early as 1536 it became clear that the rulers and intellectual leaders in what today are Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland were in a mood for religious change and that they found the Lutheran version congenial. Hans Tausen in Denmark, Olaus and Laurentius Petri in Sweden, Gebel Pederss0n in Norway, and Mikael Agrícola in Finland pioneered, many of them commuting to and from Wittenberg to be inspired by ideas of church reform. Through the centuries the Lutherans there were never successfully challenged by the Orthodox, Catholics, or Reformed and Anabaptist Protestants. They had the field to themselves and were privileged to give a Lutheran direction to the shape of the culture, to minister to virtually the whole population of Scandinavia. To this day well over 90% of the people in these northern nations are nominal members of Lutheran churches, though very few are regular in attendance or support.

Lutheranism in the New World.

The next great Lutheran move was to North America, to the United States and Canada. About 10% of the world’s 80 million to 90 million Lutherans are in the United States, where they are the fourth-largest denomination, after Roman Catholics, Baptists, and Methodists. While Swedish and Dutch Lutherans were among the earliest settlers in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and New York, they were not successful large-scale colonizers. The Lutheran movement in America did not take hold until Henry Melchior Mühlenberg, the 18th century leader, began his endeavors in Philadelphia and upstate Pennsylvania. Mühlenberg had a sense of what it took for Lutherans to adapt to North American life and innovated by developing appropriate modes of church life in a region where Lutherans did not predominate.

The great Lutheran moves to America, however, came in the middle decades of the 19th century, as part of the great migrations from the Continent to the United States. At last they were there in sufficiently significant numbers to have a cultural impact, particularly in the upper Midwest, which was then being settled. German and Scandinavian farmers and workers by the hundreds of thousands populated the Midwestern states. Many of them brought with them or were attracted to conservative styles of Lutheranism, which conflicted in part with the more accommodated and “Americanized” versions then being propagated in Pennsylvania by men like Samuel Schmucker of Gettysburg. A major leader was Carl Walther, an orthodox rigorist who helped found the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. That body and the American Lutheran Church came to be two of the three great Lutheran bodies in America—the third, the Lutheran Church in America, remaining strongest in the east.

Sheltered geographically and by their Scandinavian and German languages, most of these Lutherans did not merge into the American religious and cultural mainstream until after the pressures and blending experiences of World Wars I and II, after which their churches became more and more typically American.

By the last third of the 20th century, the three major Lutheran bodies in the United States were interactive in matters of practical church-manship and were engaged in theological conversation through the agency of the Lutheran Council in the United States of America, which has its headquarters in New York. Although to the non-Lutheran, remaining theological differences between the three groups were difficult to discern or define, many barriers to their merger remained, largely as a result of cultural differences and the absence of a common history, the latter being chiefly a result of ethnic differences.

In the public stereotype, the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod was the most isolationists and conservative, even though in 1968 it did declare itself to be in “altar and pulpit fellowship” with the American Lutheran Church. This conservatism included a rather literalistic reading of the Lutheran Confessions, an avoidance of most ecumenical ties, and a reluctance to express itself in the social realm. The American Lutheran Church, a member of some ecumenical organizations, was seen to occupy the middle ground.

The Lutheran Church in America, the largest of the three, was fully engaged in interdenominational organizational life, and it allowed for more latitude in theological expression. Having said this, it must be noted that in Lutheranism, as elsewhere, there were major exceptions to these characterizations and that differences within each of the three groups were often larger than differences between them.

Missionary Efforts.

Lutheran expansion outside Europe and North America was late and timid. In the 18th century, German Pietist Lutherans ventured to send missionaries into India, and from that time forth India remained one of the most prominent Asian outposts of Lutheranism. Efforts in the Far East had to wait until the 19th century. After World War II, Communist China suppressed Lutheranism—or at least obscured Westerners’ knowledge of it—but there were some gains on the part of Lutherans in Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Korea. A strong, largely Lutheran “younger church” in Sumatra is the Batak Protestant Christian Church.

Lutherans have been active in many parts of Africa and the Middle East and, in the 19th and 20th centuries, have known some successes there. Significant as these are in Western missionary history, and interesting as they may be intrinsically, they have been only a very small part of world Lutheranism. This has also been the case with Lutheran intrusions into largely Roman Catholic Latin America, though there are Lutheran clusters in Brazil and Argentina as a result of German migrations in the 19th century.

THE PHASES OF LUTHERANISM

For the sake of convenience, and recognizing the rough chronological edges that go with attempts at designating periods in history, Lutheranism can be seen as having passed through eight stages of development. All stages are important for understanding present realities, since heritages from each stage are widely represented in the 20th century.

Formative Period.

The period of ferment, characteristic of all formative movements, particularly in the religious realm, was filled with controversy and self-contradictory definition. This occurred during the first two decades after Luther began to promote his original spiritual vision and ecclesiastical solutions. Four illustrations will serve to suggest some of the consequences of this phase for later Lutheranism.

Luther and his partners, notably Philipp Melanchthon, were of two minds about the Catholic Church. They retained Catholic devotion to the three ancient creeds of the church. They had a high regard, as did Roman Catholics, for the ancient Christian councils and their formulations. They kept the basic outline of the Catholic liturgy as they had known it from youth. Yet Luther, in almost fanatic ways, and his humanist co-workers, in more refined ways, engaged in severe attacks on Catholicism, which became a foil for their endeavors. They had to defy the pope and emperor, even at the risk of their lives, and the vituperative language both sides used remained as a legacy among their heirs. Lutheranism has long experienced a special love-hate relation with Roman Catholicism, and has often felt itself to be most responsible for the breach in Western Christendom and most poised for reunitive conversations and efforts at shared life.

Source : pixabay.com

Lutheranism in its first stages had to be upsetting to the political order, since it was an attack of German territorialism against the Holy Roman Empire, which was bound to the Catholic religion. But the same Luther who could defy the emperor in 1520 and 1521 was himself severe against rebels in Germany in 1525, when he encouraged the princes to put down the Peasants’ War. He also criticized the princes for their excesses, but it was clear that he was fearful of anarchy and chose to side with authority and order. From this period of conflict later Lutheranism has derived a theology that both asks man in conscience to stand against earthly power, including civil and ecclesiastical repression, and yet has cultivated awe and obedience for temporal authorities to such a point that it has proverbially appeared a conservative supporter of the status quo.

The Bible was the norm by which all theology was judged in Lutheranism. However, in the earliest period, before too much definition had occurred, Lutherans had already picked up conflicting attitudes toward it. The same Luther who yielded to none in his respect for the Bible, in which he heard the Word of God and which he saw serving as “the cradle in which Christ lay,” could be almost reckless in his criticism. Sometimes he seemed to be heedless of the effect of his own remarks about biblical integrity. He was uneasy about the inclusion of some Old Testament books in the biblical canon; he could argue with St. Paul’s use of allegory; and he engaged in theological criticism of the Epistle of James, an “epistle of straw” that he felt gave support to a righteousness based on good works. Later Lutherans are still in controversy over these two attitudes to Scripture.

Ecumenically, the divided mind of Lutheranism also derives from the earliest period. On one hand, Luther could scold Desiderius Erasmus and other diffident humanists for being unwilling to start radical and revolutionary activities against Roman Catholicism, while they accused Luther of having been extreme in his approach. At the same time, Luther saw on his left reformers like Carlstadt and Thomas Miinzer who, he felt, had gone too far beyond him. To the humanists he looked like a radical, to the radicals he looked like a conservative. Lutheranism has ever after had problems with its position, which it saw to be mediating and moderating but which neither the left nor the right accepted as satisfactory.

Doctrinal Formulation.

After the original groping, excitement, and ferment, Lutheranism passed into a new stage of formulation and definition around 1530. This is the year after the Diet of Speyer, in which they had been grouped with others who were styled “Protestants.” In 1530, at an imperial Diet at Augsburg, the Lutherans presented an expository document known as the Augsburg Confession. It summarized their interpretation of historic Christianity and revealed some openness toward both Catholic and Reformed elements in the empire. From then until 1580 and the writing of the Formula of Concord, numbers of “confessional” or creedal writings were prepared, to be collected in the Book of Concord, which attempts to define original Lutheranism.

The Lutheran churches today are divided in their attitudes—slavish devotion to doctrinal formulations on the one hand and moderately critical approaches on the other. However, in the main they have come to be known through four centuries as one of the most confessional and creedal of Protestant bodies, more concerned than most with trying to return to and perpetuate the expressions of faith of their forefathers.

Expansion and Orthodoxy.

A third phase, one of expansion, was visible as early as 1536 with the Scandinavian reformations, and lived on into the next period (fourth period), universally remembered as a time when dogmatic orthodoxy prevailed. Historians of religion regularly note that after ferment there is crystallization, that an impulse in the second generation leads followers to be discontented with informal and loose organization. They find security in exact and precise definitions, which become standards by which apparent deviations are measured. In the case of Lutheranism this activity took place through much of the 17th century, when German professors wrote multivolume works on Christian dogmatics from their evangelical point of view. Two predictable reactions set in against this orthodoxy.

Pietism.

Lutheran Pietism came to prominence later in the 17th century and, like its predecessor, lives on to influence 20th century Lutheranism. Many latter-day Lutherans fuse the two, remaining attentive to orthodox definition but trying to vivify it by Pietist devotion. The great leaders of the movement, Philipp Jakob Spener and August Hermann Francke of Halle, advocated spiritual disciplines, a life of prayer, and small-group meetings for reformist purposes within Lutheranism. Pietism was particularly influential in Scandinavia and was an agent in inspiring Lutheran participation in the worldwide missionary movement.

Rationalism.

This religion of the warmed heart was soon followed or paralleled by an expression of the cool-headed intellect in the equally widespread movement called rationalism. This late 18th century movement (“from Leibniz to Lessing”) was a theological part of the German Aufklärung, or Enlightenment, and bears some resemblance to British Deism. Reason was accented over revelation, and nature was stressed at the expense of grace. The reasonableness of Christianity was featured along with a call for a new spirit of tolerance. Rationalism was soon to give way to new movements, and few people today have been directly influenced by it, but Lutheranism has been indirectly shaped by its brush with the Enlightenment.

Liberal Theology and New Confessionalism.

A seventh stage, in the 19th century, saw a bifurcation into two contradictory forces, liberal theology and new confessionalism. The first took the form of a wild variety of innovations in German university circles, beginning with the work of Friedrich Schleiermacher, who combined Reformed and Lutheran motifs in his rather subjective theology of experience. Thereafter romanticism, idealism, variations of Hegelianism and neo-Kantianism, and biblical criticism vied for attention among the intellectuals. They did not carry the day on the popular level, but their century of wrestling with what has been called “the crisis of historical consciousness” and the problems of eternal salvation based on temporal acts—for example, Christ’s death on the Cross-have had great influence on the intellectual life of later Lutherans and Protestants, never more so than late in the 20th century.

The new confessionalism was part of an awakening of religious life, liturgy, and doctrinal concern, conveniently clustered around 1817. The year 1817 was the 300th anniversary of the Reformation and the year of the “Prussian Union,” a kind of forced unity of the Reformed and Lutheran parties that seemed to be a threat to pure Lutheranism. Out of this “back to Luther” movement came a passion for orthodoxy, mixed with a more stylized worship, richer piety, and missionary and humanitarian concerns in Germany, Scandinavia, and the United States.

Ecumenism.

The 20th century has been marked by an ecumenical tendency, as Lutherans wrestle with their own past phases and relate to each other and to non-Lutheran Christians. Early in the 20th century, through men like Sweden’s Archbishop Nathan Söderblom, they became active in exploring their relations with Anglican, Reformed, Baptist, and other Christians. Ever since, they have regularly been enthusiastic participants in ecumenical conversations, to which they have brought their doctrinal concerns. At the same time, they have tried to regroup, through a Lutheran World Convention and a Lutheran World Federation and through countless mergers in a nation like the United States, where varieties of immigrations and disputes had divided them into scores of jurisdictions and denominations. During this period, Lutherans have also lived under totalitarianism as few Protestants have. Those who opposed nazism in Germany and those who suffered under communism in eastern Europe made common Cause with non-Lutherans.

THE CULTURAL STANCES OF LUTHERANISM

From what has preceded, it can be seen that Lutheranism, like most religious forces, lives in constant involvement with its host cultures and leaves its stamp on its environment. In no sphere has this tendency been stronger or more filled with problems than in Lutheranism’s varied experiences with civil and political authority and change. Luther was himself a rebel, and his theology committed him to views that kept the civil and religious spheres quite distinct. But he depended early on the protection and governance of existing civil authority and abhorred the thought of anarchy. In Germany and Scandinavia the “princes’ often became the equivalent of bishops, and the clergy often became something like civil servants. Lutherans were taught to accept literally St. Paul’s words (Romans 13:1-7) that they must obey all magistrates— and they took this to mean obeying evil rulers.

A tradition of passivity and acquiescence resulted, to such an extent that anti-Germans in the Nazi era sometimes claimed that Luther was “Hitler’s spiritual ancestor.” If most Lutherans went along with the totalitarian regime, however, the Nazi experience revealed that latent conscientious rejection could be activated and acted upon, and in Bishop Eivind Berggrav of Norway and in the martyred Dietrich Bonhoeffer, of Germany, one could see styles of political resistance chosen by significant Lutherans.

A second Lutheran trait, in contrast to what is frequently the Reformed attitude, has been a devotion to the arts, particularly to music. Music ranked second only to theology in Luther’s scheme of things. Lutheran congregational singing is usually robust and lusty. Great composers like Johann Sebastian Bach could develop the Lutheran chorales (hymns) into majestic works of art. The visual arts have been secondary, but now I despise them.

An affirmation of the arts and musical expression has often gone along with positive views of nature and the things of the earth. Here Lutheranism has been equivocal. Those of Luther’s own heritage—he loved beer and bowling—have tended to be rather earthy and playful. But the parallel Pietist tradition has often led millions of Lutherans to a world-denying and gloomy approach to life. On few points is it more difficult to generalize than on a common Lutheran “lifestyle.”