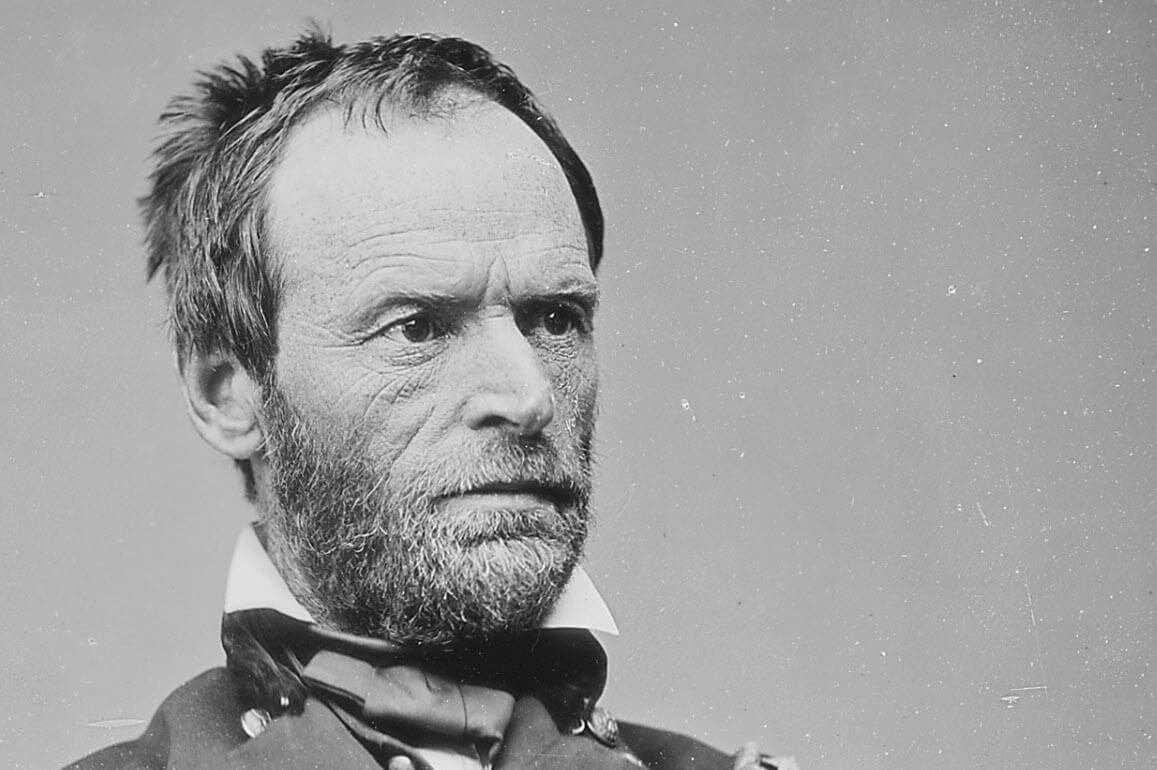

Who was William Tecumseh Sherman? Information on the biography, life story, works and military career of American general William Tecumseh Sherman.

William Tecumseh Sherman; (1820-1891), American general, who was one of the greatest Union commanders in the Civil War. Possessing a quick and incisive mind and a strong personality, Sherman saw the war in broad strategic terms, and he comprehended its social, political, and economic aspects more clearly than did most military men.

Sherman was born on Feb. 8, 1820, at Lancaster, Ohio. He was named Tecumseh because his father admired the Shawnee Indian chief of that name. At the age of nine, he was adopted after his father’s death by Thomas Ewing, who had been active in national politics. His foster mother insisted that “William” be prefaced to his name. Through his foster father’s influence, Sherman was appointed to the U. S. Military Academy. He graduated in 1840, sixth in a class of 42, ranking highest in engineering, rhetoric, mental philosophy—and demerits.

Source: wikipedia.org

Early Career.

Commissioned July 1, 1840 as a 2d lieutenant in the 3d Artillery, Sherman was stationed in Florida and as a 1st lieutenant commanded a small detachment at Picolata. Transferred in 1842 to Fort Moultrie, S. C., Sherman spent four happy years in Charleston, captivated by the social life. In the Mexican War he was stationed in California and saw no fighting. In 1850 he returned to Washington, D. C., where his foster father was serving as secretary of the interior, and married his foster sister, Ellen Boyle Ewing.

As a captain in the commissary department, Sherman served in St. Louis, Mo., and New Orleans, La., but discouraged by his prospects and the “dull, tame life” of the Army, resigned from the service on Sept. 6, 1853. Next he represented the St. Louis banking firm of Lucas, Turner & Co., in San Francisco, but the panic in the goldfields during 1854-1855 doomed the San Francisco branch bank. He sought unsuccessfully to get back into the Army, and went to Kansas to manage real estate owned by his family. At Leavenworth during 1858-1859 he tried a brief fling as a lawyer, but was quickly betrayed by the temper that went with his red hair and beard. With the help of two army friends, Pierre G. P. Beauregard and Braxton Bragg, he secured appointment as superintendent of the state military academy at Alexandria, La.

An indulgent teacher devoted to his students, Sherman began to reveal that paternalistic streak that during the Civil War made him the idol of the Western armies. In dismay he watched secession sweep through the South, and when Louisiana left the Union in January 1861, Sherman resigned from the only job he ever really had liked, predicting that the South was rushing into disaster and writing his daughter that “men are blind and crazy.” Irritated when President Abraham Lincoln shmgged off his advice about the situation in Louisiana, Sherman went to St. Louis resolved to sit out the war as president of the Fifth Street Railroad.

Civil War Service.

Sherman was vigorously roused by the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861. He regarded President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers for three months’ service as trifling with a desperate emergency. The Army was reaching for trained officers, and Sherman accepted a commission as a colonel.

He commanded a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas). That confused action, which ended in a panic of the Union troops, was Sherman’s first battle experience, and it convinced him that he was uniit for the responsibility of an independent command.

But Lincoln ignored Sherman’s plea that he be spared sueh responsibility. He promoted Sherman to brigadier general and sent him to Kentucky to share a command with Gen. Robert Anderson, who had defended Fort Sumter in the war’s first engagement.

Here Sherman was nervous and confused. He suffered under the delusion that his forces were about to be overwhelmed by superior Confederate power. He so unnerved those around him that the Cincinnati Commercial published a report that he was insane. He was called “Crazy” Sherman, and his army career seemed at an end. But Gen. Henry W. Halleck, in command at St. Louis, recognized Sherman’s special talent in military planning and gave him another chance. Sherman worked on the plans for Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign against Forts Henry and Donelson in early 1862. His admiration for Grant grew into a devoted friendship.

Under Grant, Sherman commanded brilliantly at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862). When Grant, in despair over criticism of his conduct of the battle, talked of leaving the Army, Sherman was able to persuade his friend to await a turn in fortune.

Promoted to major general, dating from May 1, 1862, Sherman played a principal role in the campaign under Grant that led to the siege and capture of Vicksburg. Sherman began with a failure in that campaign, when with an expedition of 32,000 men he floundered at Chickasaw Bluffs (Dec. 27-29, 1862). He cooperated with Gen. John A. McClemand in the capture of Fort Hindman, Ark. (Jan. 4-12, 1863), and thereafter commanded the 15th Corps for Grant (Jan. 4-Oct. 29, 1863) in the series of engagements that brought about the fail of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. He opposed Grant’s plan to cut loose from his base of supplies and live off the land as he swept around Vicksburg, coming at the city from the rear. Later in the war, Sherman taught his own armies to live off the country.

Sherman succeeded Grant as commanding general of the Department of Tennessee. Later, joining Grant in the Chattanooga campaign, Sherman held the flank against fierce assaults while Gen. George H. Thomas swept to victory on Missionary Ridge (Nov. 24-25, 1863). By forced marches Sherman pushed his troops to Knoxville just in time to save Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, who was besieged there, from possible disaster (Dec. 3-4, 1863).

In Georgia and the Carolinas.

When in March 1864, Grant became commander of ali the Union armies, Sherman was assigned to command in the South, mounting a campaign to parallel Grant’s drive in Virginia. With about 99,000 men, Sherman started from Chattanooga on May 7, and on Sept. 2 his men occupied Atlanta, the key city of the Deep South, after a siege. In this campaign Sherman’s strategic skill was well displayed. He fought few major battles, but maneuvered to outflank his foe time after time.

From Atlanta, Sherman conducted his farnous March to the Sea (Nov. 16-Dec. 22), leading 62,000 men in a broad swath through the heart of Georgia, ravaging the countryside. “I can make Georgia howl,” he said, and the psychological impact of this march was devastating to the South.

When Sherman’s army entered Savannah, he wired Lincoln: “I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns, plenty of ammunition, and 25,000 bales of cotton.” On Jan. 15, 1865, Congress voted its thanks to Sherman for his “triumphal march.”

In February 1865, Sherman headed north through the Carolinas, aiming at a junction with Grant’s forces in Virginia, which would end the war. Confederates led by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston could offer only token resistance. The last battle was fought at Bentonville, N. C., on March 19-21. When Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant in Virginia on April 9, Johnston’s position was hopeless. Sherman accepted his surrender near Durham, N. C., on April 26. Sherman was sharply criticized for the generosity of the terms he offered.

Postwar Years.

Commanding the military division of the Mississippi from 1865 to 1869, Sherman was promoted to lieutenant general (1866) and to full general (1869). When Grant was inaugurated president in 1869, Sherman became general in chief of the army, a post he held for 14 years.

Sherman remained a popular figüre, known for his broad and positive views on public affairs. He was much in demand as a speaker, especially at veterans’ meetings.

Periodically, a boom was begun to draft Sherman as a presidential candidate. His telegram in response to such an appeal from the Republican national convention in 1884 was a classic example of brief, forthright statement: “I will not accept if nominated, and will not serve if elected.”

Sherman published his Memoirs in 1875. He died in New York City on Feb. 14, 1891.

mavi