What did Leonardo Da Vinci do? Information about Leonardo Da Vinci works, paintings, drawings, techniques, methods and contributions to science.

Few of Leonardo’s ambitious projects were ever realized, but the full range of his intellect and imagination is manifest in his famous notebooks. Bequeathed to his disciple Francesco Melzi, these manuscripts remained together for the most part through the 16th century. By 1600, however, they were dispersed and are now preserved in various libraries, chiefly in Milan, Turin, Paris, London, Windsor, and Madrid. Encyclopedic in the scope of subjects covered, the notebooks comprise several thousand densely filled sheets of drawings, diagrams, and text. The text is written in reverse—that is, to be read from right to left. Since Leonardo was left-handed, mirror writing was more comfortable and natural for him.

What these notebooks reveal is that, despite their diversity and the failure of their author to achieve the full intellectual synthesis he sought, there is an ultimate unity to Leonardo’s work. And the key to that unity is the process of vision. Man’s eye, for Leonardo, is his greatest sensory organ, the means whereby he acquires his knowledge of the universe. Hence artistic perception could be equated with scientific comprehension. “Painting is a science,” he declared, in response to the traditional view that it was a mechanical activity excluded from the ranks of the liberal arts. And, he further argued, since painting alone appeals directly to the eye, like nature itself, it is to be judged the noblest of the sciences.

Painting.

Leonardo, like other early Renaissance masters, set down his thoughts on art. In these notes, known as his Treatise on Painting, quite probably intended for publication, he asserted the nobility of painting, comparing it not only with other sciences and philosophy but with poetry, music, and sculpture—in each case demonstrating its superiority.

Aerial Perspective.

With the appearance of Alberti’s Delia pittura (1435), the first Renaissance treatise on painting, the mathematical basis of the art had been proved with reference to the system of pictorial perspective. Leonardo continued this tradition, but he extended the argument beyond the geometry of linear construction to consider the problems of atmospheric, or aerial, perspective. Light and shade had been critical factors in the new illusionism of early Renaissance painting. The chief concern of Leonardo’s predecessors, however, was essentially to define the location and solidity of objects in space. The spatial continuum they postulated as the container of those solids remained of somewhat secondary importance. Leonardo turned his attention—that is, his vision—to that space itself, appreciating the substantiality of its atmosphere. Hence his notebooks are filled with observations on the qualities of air as well as of light, on the “obscuring medium” interceding between the eye and the object and affecting the color and clarity of the latter. This concern led him to further, more specifically scientific, explorations of the natural phenomena themselves—a dialectical circuit of reciprocity that serves ultimately to organize and unify Leonardo’s activities as artist and scientist.

Visual Unity.

From the beginning of his career as a painter, Leonardo’s keen observation of nature affected his response to the stylistic conventions in which he was trained. He could not fully accept and work in a style composed of separate, discretely bounded elements—the style his contemporary Botticelli refined to graceful perfection. Leonardo perceived in nature a unified visual field, which he sought to create in his painting. The unfinished panel of the Adoration of the Magi illustrates how, even in this early period, he tried to establish in his pictures that visual unity through large-scale distribution of light and shadow. Here, shadow serves a larger purpose than merely defining the solid appearance of single objects, functioning instead to define that “obscuring medium” and in the process denying some of the discrete boundaries of the objects.

Leonardo further developed this principle in his subsequent, paintings, creating a hazy atmosphere or smoky tone (sfumato), which he describes and analyzes so frequently in his notebooks. Actually toning down the contours, he softened his forms to achieve a greater blend between the object rendered and its surrounding atmosphere. This technique in turn also involved a muting of color, so that even his early work is distinguished from the higher-keyed and more intensely saturated hues of contemporary Florentine painting. It was precisely this kind of tonal painting that established an influential model for various individual artists and schools of Italian painting in the 16th century.

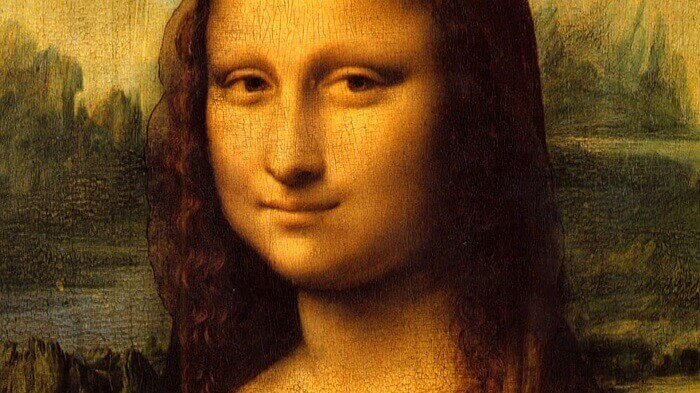

Portraiture.

In the portrait of Mona Lisa, the wife of a Florentine merchant, Francesco di Bartolommeo del Giocondo—hence the alternate title for the painting, La Gioconda—Leonardo demonstrated the full possibilities of his manner. He also set an example of compositional control and expressive subtlety that established a new standard of portraiture in European painting from Raphael to Rembrandt. While the full effect of the picture depends on the juxtaposition of the serene face and figure of the sitter in the foreground with the turbulent backdrop of craggy rocks and mountains cut by swirling rivers, its most memorable and haunting aspect is the enigmatic mask of the lady herself. The extremely delicate sfumato modeling around her features sets them into quiet motion. Mona Lisa’s slight smile, suggested rather than stated, seems to imply a potential expression on her basically bland face. Through such understatement and gentle inflection, Leonardo created a psychological world, complementing the physical one, which he considered the painter’s first mimetic concern.

Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo’s studies of the human head document his intense interest in the psychology behind physiognomic form. Following the standard precepts of Renaissance art theory, he wrote that in any painting “the movements of each figure should express its mental state, such as desire, scorn, anger, pity, and the like,” and that the “intentions of the soul” should be legible in the face. Just this attitude molded Leonardo’s conception of the Last Supper. The entire composition is dramatically unified by a single moment. The varied expressions and gestures of the disciples reveal their several responses to Jesus’ declaration: “Verily I say unto you, that one of yoii shall betray me” (Matthew 26:21). With these words Christ, the still center, becomes the prime mover in the composition, the effective cause of the physical and emotional action. It is typical of Leonardo to seek such a psychological rationale and dramatic unity for his work.

Compositional Unity.

From a strictly formal point of view, the question of unity is central to Leonardo’s art. Rejecting the pictorial multiplicity and anecdotal detail of late 15th century painting, he developed instead a new sense of compositional hierarchy of broader forms organized on a larger scale. The grandeur and clarity of his design, however, were calculated to contain within the stable formal structure a diversity of conflicting forces.

This compositional dialectic underlies the dynamics of Leonardo’s pictures. Just as in a large dimension the Last Supper subsumes the different actions of its participants into the overall conception, so on a smaller scale, in individual figures, he modifies the traditional con-trapposto pose (with the upper part of the body twisted in the opposite direction from the lower) to achieve a new vitality. The problem of posing single figures so as to obtain a balanced combination of movement and stasis was central to early Renaissance art. Leonardo’s solution involved the addition of a new dimension. His figures break the frontal plane to move about the central axis defined by their own torsos, as in Leda and the Swan, known through his preparatory drawings and painted copies by followers. The resulting serpentine movement established a new type, the figura serpentinata (serpentine figure), which, like so many products of the master’s imagination, proved to be a basic ingredient for subsequent 16th century styles.

In the Battle of Anghiari, Leonardo had his greatest opportunity to demonstrate the power of his art. In this commission he had to assemble in a vast landscape setting a multitude of human figures and horses in combat. On many occasions he asserted in his notebooks that the depiction of a battle was the greatest challenge to a painter. The central motif of Leonardo’s cartoon, a unit composed of centripetal and centrifugal forces held in a dramatic equilibrium, presents an image of savage struggle, with horses as well as warriors actively engaged in the bloody fray. As is so frequently true of his art, the design is a fuller realization of themes that had preoccupied him at least since his Florentine apprenticeship. A similar group of fighting horsemen appears in the background of the Adoration of the Magi. The margins of many early drawings contain apparently casual notations of furious faces of men, horses, lions, and imaginary beasts—images already declaring Leonardo’s interest in comparative anatomy.

Sculpture.

Although not a single work in sculpture by Leonardo himself survives, the artist was celebrated as a sculptor. His first invitation to Milan was offered to him primarily in recognition of his training by Verrocchio in the art of bronze casting. The project that occupied most of his time in Milan was the monumental equestrian statue to Francesco Sforza. Fully aware of the examples of Donatello’s Gattamelata in Padua and of Verrocchio’s own monument to Colleone, then being erected in Venice, Leonardo and his patrons were determined to surpass them. In terms of sheer dimensions—the horse alone was to stand 22 feet (6.6 meters) high—and of the dynamics of the design, Leonardo’s statue would have marked not only a new kind of aesthetic conception but also a great technical feat of casting. But this project, like so many others, was destined to remain unrealized. It is known essentially through the many preparatory drawings. In 1493 a clay model of the horse was put on public display and greatly admired. When Milan fell to the French in 1499 the clay model was destroyed by French archers who used it for target practice. Leonardo’s second equestrian project, the Trivulzio tomb, never even reached the model stage.

Leonardo’s talents in sculpture were recognized particularly in the realm of bronze casting. He disdained stone carving as “a most mechanical exercise often accompanied by much perspiration.” This particular attitude was one of the sources of his conflict with Michelangelo, for whom carving in stone was the only legitimate form of sculpture and, indeed, the highest form of art.

Techniques and Methods.

Constant experimentation with artistic media and techniques characterizes Leonardo’s career. His use of reinforcing iron braces solved the problems of balance in sculpting and casting the open form of a rearing horse, anticipating the solution later developed by Galileo. In painting, however, Leonardo’s experimentation seems to have been motivated by an impatience with traditional media. His manner of working, in bursts of intense activity preceded and followed by periods of contemplation, was ill-suited to the painstaking demands of fresco technique. Thus in executing the Last Supper, he invented a new technique of mural painting, a complicated procedure of applying an oil and tempera medium to a specially prepared surface. This technique freed him to work at his own pace and also allowed him to achieve softer pictorial effects than were possible in fresco. But the experiment failed. The pigment soon loosened from the wall, and in the artist’s own lifetime the picture was already in ruinous condition.

Leonardo’s sense of artistic creation, recorded in his notebooks and evident in his works, was as radically innovative. Despite the precision of his drawings and the studied nuances of his painting, he did not share his contemporaries’ attitude toward polished craftsmanship. The artist, he asserted, works with his eye and mind and then with his hand. Artistic process is a continuous activity, which does not stop with the completed object. The imagination unceasingly receives stimuli from the vast world of visual phenomena. The artist, like nature itself, is constantly creating. It is significant that Leonardo is the first master of the Renaissance to leave behind a large corpus of drawings. He was perhaps more fascinated by the fact of creative power than by its final finished products, and this fascination may account in part for the pattern of unfinished work characteristic of his career.

Architecture and Military Engineering.

Although Leonardo never actually constructed a building, he was held in the highest esteem as an architect. His role in the history of Renaissance architecture is probably as critical as it is in the other arts. The many architectural drawings in his notebooks range from plans for the dome of Milan Cathedral, through studies for churches, palaces, urban plans, and military architecture, to an enormous bridge over the Bosporus for Sultan Bayezid II. Indeed the drawings themselves are important landmarks in the history of architectural rendering. They are the first architectural drawings of the Renaissance to combine ground plans, perspective views of exteriors and interiors, and even building cross sections for a full graphic presentation.

One of the major concerns evident in Leonardo’s architectural notebooks is the centralized church plan, a form based on the divine symbolism of the circle, which had fired the imagination of Renaissance architects since Brunelleschi. What Leonardo oifers in his drawings, which were preparatory to a treatise on architecture, is a pattern book of types, a variety of solutionslto a single problem. In Milan he shared his architectural interests with Bramante, who later realized the possibilities of the centralized plan on a monumental scale in his design for the new St. Peter’s in Rome. From a historical point of view, Leonardo’s drawings are a link between the simpler spatial compositions of early Renaissance architecture and the more complex and dynamic spaces of Bramante’s High Renaissance style.

Leonardo’s plan for an ideal city is astonishingly modern in its attention to problems of hygiene and population density. But the most striking aspect of his plan is the conception of a city on two levels connected by stairways and ramps. The domestic and cultural activities on the upper level are separated from the traffic below. Furthermore, the lower level also includes a network of canals intended to serve as an efficient sewage system. In this way Leonardo not only applied his knowledge of hydraulics but also took advantage of existing canal systems on the Lombard plain to solve a basic health problem of the crowded city.

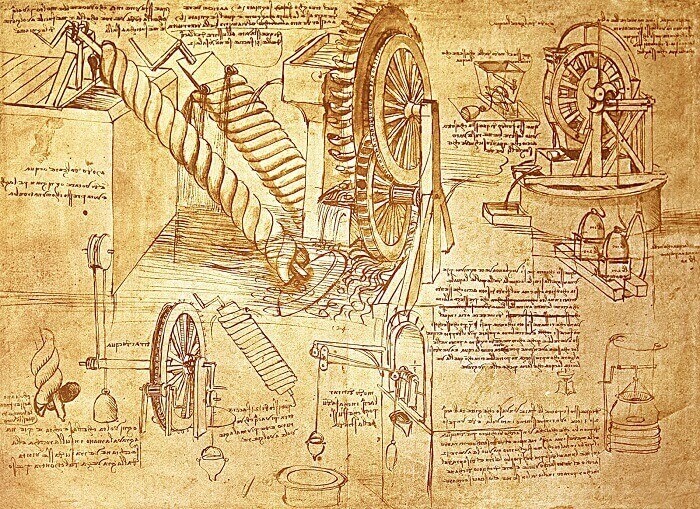

In his letter to the Duke of Milan, Leonardo had emphasized his skills as a military engineer, offering services from the designing of portable bridges to the construction of cannon (some of which resemble the modern machine gun), battleships, and mechanically propelled armored cars. His plans for a fortress reveal his awareness of the fundamental changes occurring in warfare with the introduction of gunpowder. Leonardo’s defensive structure is designed to withstand this new form of attack. The walls have not only been strengthened, but their surfaces and angles have been curved to counter the angle of incidence of an artillery shot. Moreover, his fort does not stand tall and visible like a medieval castle but is set low into the ground so as to reveal a minimal profile. Leonardo’s interest in ballistics and his study of missile trajectories thus served him for olfensive and defensive designs.

Science.

While Leonardo always considered himself a painter and was proud of his profession, his intellectual curiosity in natural phenomena gradually led him away from the practice of his art. During the final decade of his life he did very little painting. His contemporaries commented on his increasing reluctance to accept commissions and noted his growing involvement with mathematics and science. But for Leonardo himself this activity was intimately related to his sense of intellectual responsibility as an artist. It was the logical extension of his conception of painting as a science. The immense range of his scientific studies is unparalleled. It includes mathematics, optics, mechanics, anatomy and physiology, zoology, botany, geology, and paleontology. And the vision informing those studies is just as impressive. His notes toward a treatise on the flight of birds, for example, inspired him to consider a flying machine for man. The presentation of his findings in both word and image testifies to the fundamentally visual aspect of his imagination.

Biology.

On another level, Leonardo’s desire for knowledge was inspired by his own passionate response to nature. In his botanical studies, for instance, he represented particular plants rather than the generalized type of the species. By carefully investigating the special, individual object before him, he discovered and depicted the peculiar qualities of its organic function as well as the physical aspect of its outer form.

Similarly, although he was not the first Renaissance artist to dissect the human body in search of anatomical knowledge, he went far beyond his contemporaries’ concern with the purely mechanical structure of the body to discover the fuller truth of its functioning. Investigating and describing the internal organs, he studied the processes of breathing, digestion, and reproduction. Studying the arterial system as well as the heart, he focused on the problem of the circulation of the blood—without, however, fully recognizing it. The anatomical treatise he projected was to begin with the moment of conception and then describe the nature of the womb, the development of the fetus, the birth of the infant, and the subsequent growth of the human body. Modern anatomical study, though born of the desire of early Renaissance artists to achieve a pictorial imitation of the body, assumes its first scientific form in Leonardo’s notebooks.

Mathematics.

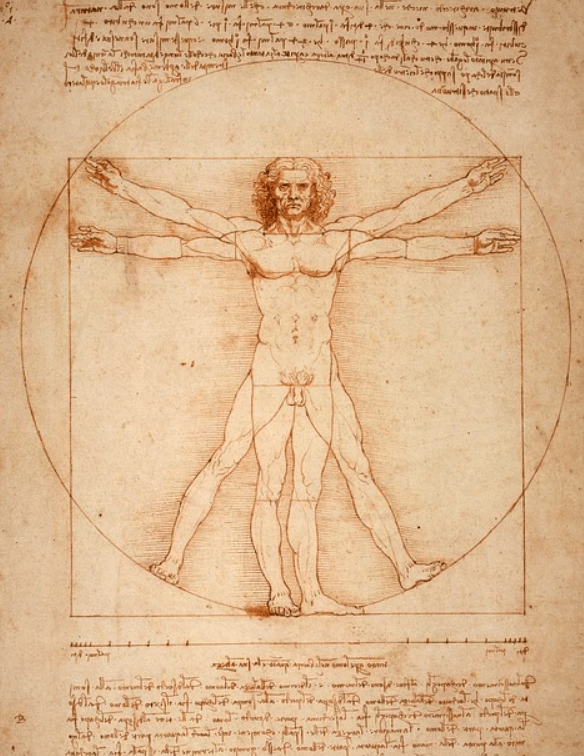

“Let no one read me who is not a mathematician,” wrote Leonardo in one of his anatomical manuscripts. In so linking the human form with mathematics, he was continuing a Renaissance tradition with roots in classical antiquity. His famous drawing of the figure related to the circle and the square (Aceademia di Belle Arti, Venice) illustrates a proportional canon set forth by the Roman architect Vitruvius. Mathematics provided a key to the order of the universe for the Renaissance mind, and geometry in particular made manifest the regularity of visual forms.

For Leonardo, then, mathematics meant essentially geometry, in which he received his advanced training with Luca Pacioli at the Milanese court. The certainty of mathematics, “the only science which contains within itself its own proof,” appealed to the artist’s imagination. Indeed it was precisely as an artist that Leonardo appreciated geometry as the visualization of abstractions—abstractions which, like the square root of 2, defied exact arithmetical definition. Moreover, geometry provided the basis of the science of painting, since the perspective construction of Italian Renaissance painting was an application of geometric principles.

Optics.

It seems only natural that Leonardo should have inquired further than his predecessors into the elements of Euclidean optics. The very process of vision that so fascinated him as a painter was dependent on light, and he devised a number of experiments to describe and verify the phenomena he himself had so carefully observed. On the circular diffusion of light, he wrote: “Just as the stone thrown into the water becomes the center and cause of various circles, and the sound made in the air spreads itself out in circles, so every body placed within the luminous air spreads itself out in circles and fills the surrounding parts with an infinite number of images of itself.”

While there is in such an observation a definite relation to modern theories of light diffusion, Leonardo may in fact have been familiar with ancient sources of this doctrine. Here, as in many other instances, his achievement was that of subjecting such inherited theories to the empirical proof of experimentation. Yet he lacked the mathematical sophistication to formulate an abstract principle defining the phenomena he observed, and this very failure is one of the crucial factors separating him as a scientist from the generation of Galileo and Kepler. In the same way, his mechanical investigations offer demonstrations of the principles of friction, transmission, and resistance by a series of experimental models, but he was incapable of translating those observations into abstract mathematical language.

Geology.

It was initially as an artist that Leonardo began his studies of the earth itself. For him the earth was a living organism, analogous to the human body:

We may say that the earth has a spirit of growth, and that its flesh is the soil; its bones are the successive strata of the rocks which form the mountains; its cartilage is the tufa stone; its blood the springs of its waters. The lake of blood that lies about the heart is the ocean. Its breathing is by the increase and decrease of the blood in its pulses, and even so in the earth is the ebb and flow of the sea. And the vital heat of the world is the fire which is spread throughout the earth.

Moreover, examining fossils and musing upon their origins, he developed a theory of the origin of the earth, based in part on his own observation but also deriving in part from inherited concepts, such as those of Ptolemy.

Leonardo viewed as fundamental to the formation of the earth’s surface the conflict between rock and water, water being at once the great creative and destructive force. Perhaps nowhere more than in his studies of the movement of water did he so closely approach what might be considered a unified theory. Patterns of flow and counterflow are recorded in drawings of great beauty, in which the inventiveness of the imagination is of greater significance than the accuracy of the observing eye. Leonardo compared the movement of water to that of human hair. This analogy, illustrated in his drawings, reveals much about the operation of his mind, for he attempted to depict forces that are invisible to the human eye. The beautiful whirlpools of his designs make both scientific and aesthetic sense in terms of their dynamics of movement. But when we consider how Leonardo applied these same forces on a macrocosmic scale, as in the late Deluge drawings (Windsor Castle), we must conclude that the objective eye of the empirical observer was indeed guided by a larger a priori concept or vision.

Conclusion.

For all his rejection of accepted authority and his insistence on personal experience, Leonardo’s scientific method was not totally inductive. The fundamental order he was seeking in the encyclopedic vastness of his manuscripts was finally beyond the reach of the pure scientists. The order that is indeed manifest derives from the genius of the artist, depending as it does on his ability to visualize the invisible.

Leonardo dealt in the realm of visual ideas, and herein lies the source of his powerful intellectual achievement as well as of his ultimate failure to systematize his findings on the more universal level of abstract principles. His scientific thought, like his art, was basically experimental and descriptive. His tools were his artistic talent and, nearly as significant, his language. Like his German contemporary Dürer, Leonardo had to refine his native language in order to make it work for him. The Latin of Renaissance culture was inadequate for new needs. Seeking a more precise descriptive language in Italian, he subjected his thoughts to constant restatement, reformulating them in an attempt to obtain maximum clarity and efficiency of expression. Thus his prose style itself must be counted as one of Leonardo’s great achievements.

mavi