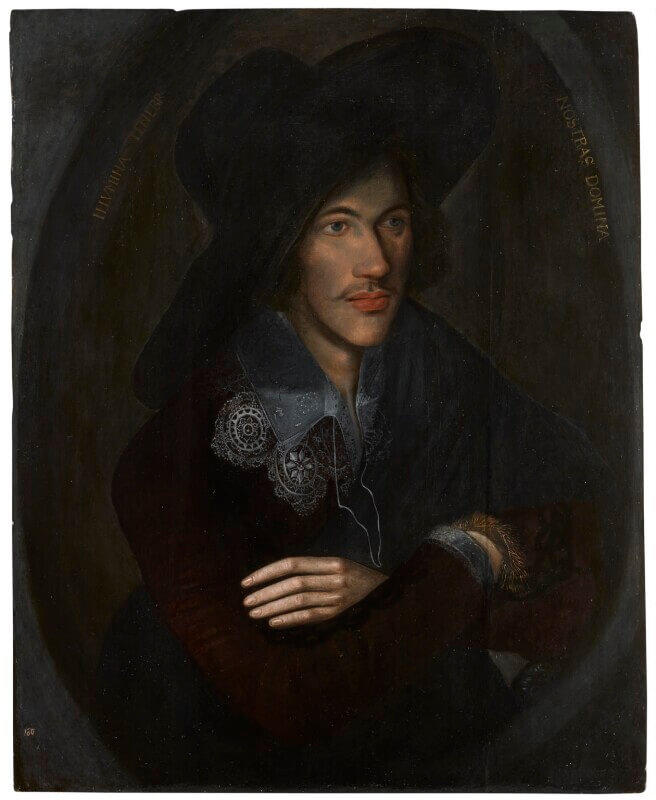

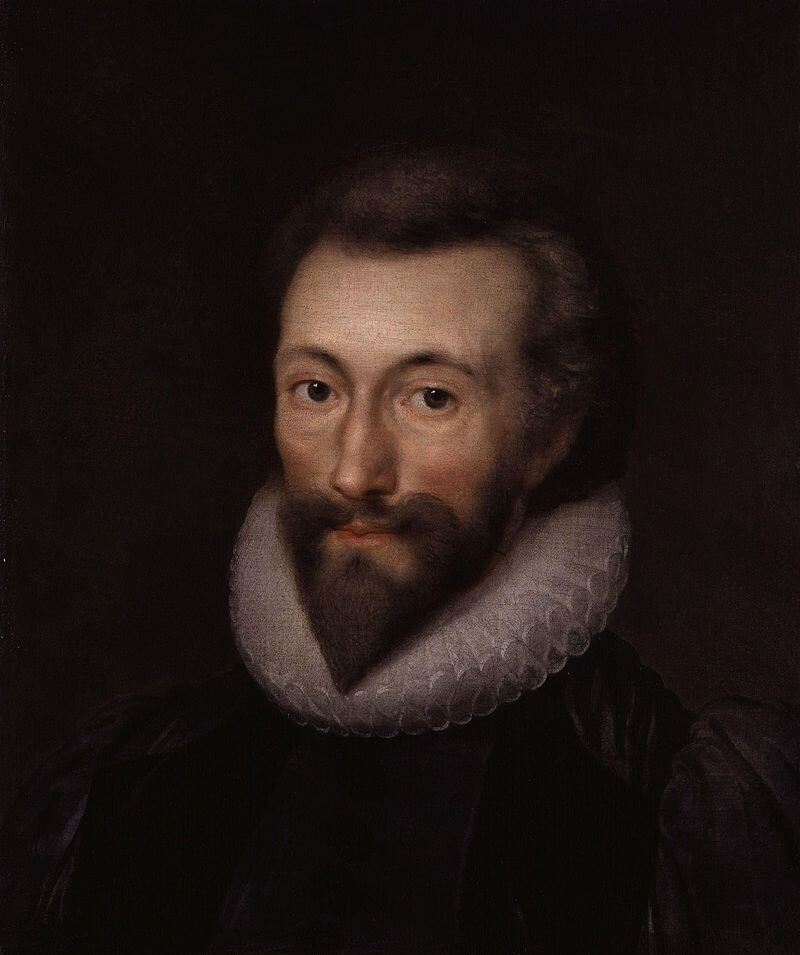

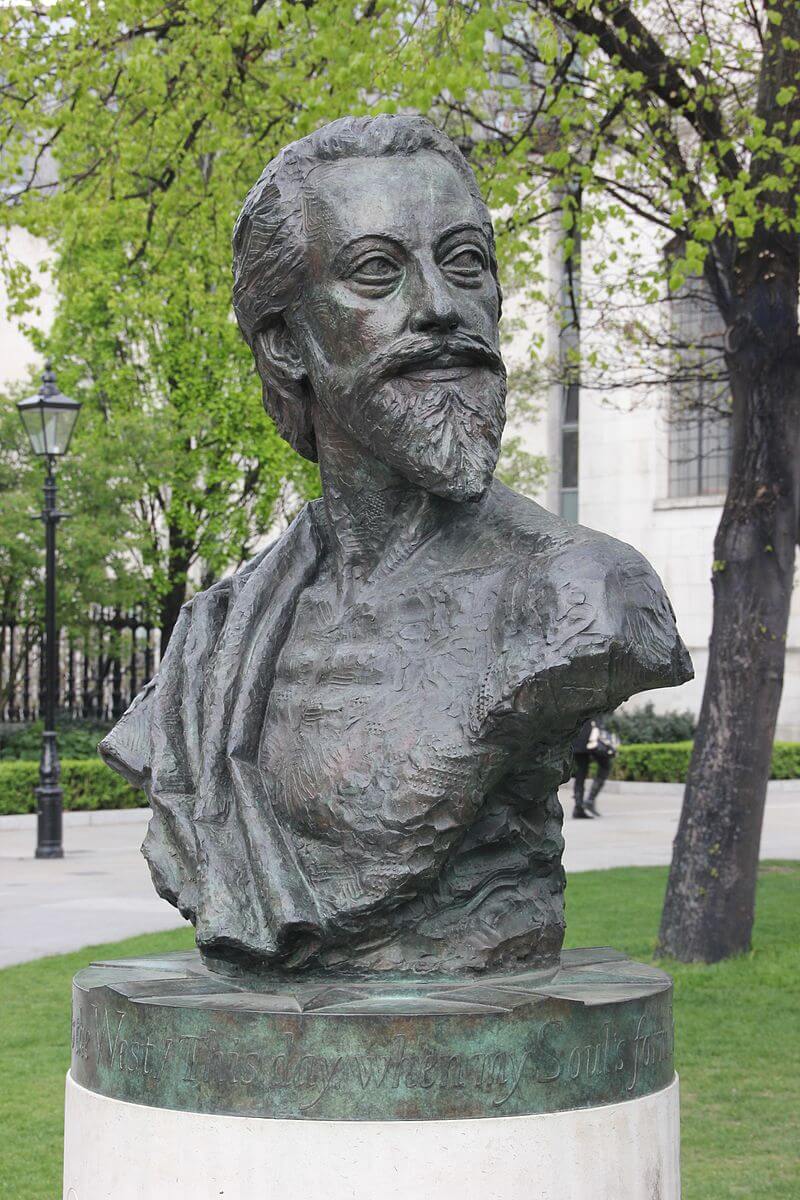

Who is John Donne? Information about English Poet John Donne biography, life story, poems and works.

John Donne (1572-1631), English poet, preacher, and prose writer, who was the chief exponent of the “metaphysical” style in poetry and a towering figure in 17th century English literature. Little of his poetry was published during his lifetime. His love lyrics, both cynical and passionate, together with the elegies and satires of his early youth, did not see print but were circulated widely in manuscript among the courtly wits and intellectuals of Elizabethan and Jacobean London.

Rediscovered in the 20th century after 200 years of relative neglect, Donne has enjoyed among modern readers a remarkable popularity that shows no sign of diminishing. His influence on 20th century English and American poetry has been incalculable. His example was instrumental in forging the poetic styles of Yeats and T. S. Eliot, the two dominant forces in modern English poetry, and literary historians and critics agree in ranking Donne as one of the greatest of English poets. Future generations are unlikely to revise this estimate.

Source : wikipedia.org

Life:

Rorn in London of a firmly Roman Catholic family, Donne studied at Oxford and possibly also at Cambridge but did not take a degree at either university; his faith made it impossible for him to swear the required oath of allegiance to the Protestant queen. He studied law at Lincoln’s Inn in London during the 1590’s and began an intensive study of theology in order to investigate the opposing claims of Protestantism and Catholicism. He had other pursuits as well: a contemporary describes him at that time as “very neat, a great visitor of ladies, a great frequenter of plays, a great writer of conceited verses.”

Donne seems to have traveled on the Continent at some point during these years, and he took part in the Earl of Essex’s military expeditions against Spain in 1596 and 1597. The fact that, in 1598, Donne became secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, lord keeper of the great seal, makes it probable that by then the poet had become at least nominally an Anglican. In 1601, Donne fell in love with Anne More, niece of Sir Thomas More and daughter of Sir George More, chancellor of the Garter. They were secretly married, and Sir George’s displeasure led to Donne’s dismissal from his post, imprisonment for a brief period, and the ruin of his hopes for a career in public life.

The next 10 years of Donne’s life were marked by penury and desperation. Until Sir George finally relented to some degree, Donne and his growing family were obliged to depend largely on the charity of friends and the generosity of patrons, the chief of whom was Sir Robert Drury, in memory of whose daughter Donne wrote the great Anniversary poems. Other patrons included some of the great ladies of Jacobean England, most importantly Lucy, Countess of Redford. In this period Donne also published works in which he supported the Anglican position against that of the Catholics.

Friends had often urged Donne to take holy orders, but he had been reluctant to do so—perhaps because of feelings of unworthiness as a result of the sexual indiscretions of his youth, perhaps because of lingering doubts as to the identity of the true church. In 1615, after repeated pressures from King James I, Donne was ordained a minister of the Church of England. He rapidly established himself as one of the greatest preachers of the age, was almost immediately made chaplain to the king, and in 1621 was appointed Dean of St. Paxil’s Cathedral in London, a post he retained for the rest of his life.

Donne’s death, in London on March 31, 1631, was as vivid and theatrical as his life. After preaching his last sermon—described by his friend Isaak Walton as “his own funeral sermon”—he took to his bed and had his portrait painted in his shroud, keeping the picture for his contemplation until he died a few days later.

Poetry:

Some of Donne’s early poetry shows the Renaissance trait of classical imitation. His elegies (which are not elegies in the modern sense of being poems of lament) are modeled on the Amoves of Ovid, and his satires show the influence of Juvenal and Persius.

For a long time it was believed that all of Donne’s love poetry was composed during his youth and that his later years were given over to the writing of religious verse and prose, but modern scholarship has established that some of the Songs and Sonnets (as they were called in the posthumous editions) were written as late as 1617 and that the great sequence Holy Sonnets was written for the most part as early as 1609. The pattern that thus emerges is more in accord with what is known of Donne’s complex yet strangely unified personality. In their own way the High Sonnets, too, are love poems: the speaker has changed his object from an earthly mistress to a transcendent Deity, but in the divine poems, as in the profane ones, a desperate desire for absolute union finds expression in witty intellectual analogies that attempt to bestow a unity on the scattered fragments of experience. It is significant that whereas the amorous poems are permeated with religious imagery, the devotional poems operate largely through erotic imagery.

Source : wikipedia.org

There is little physical description of any sort in Donne’s poetry. Specifically intellectual quality manifests itself in the structure of his poems, which is typically logical or argumentative, and in their figuration, which depends heavily on the device of the “conceit,” or far fetched metaphor. Donne’s conceits, unlike those of some other baroque poets, are usually based not on an extravagant perception of physical resemblance but rather on an intellectually perceived resemblance of function or inner nature. Such is the case in the famous lines from A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning, in which he addresses his beloved (according to tradition, his wife Anne) from whom he is about to be separated. Referring to their two souls, he writes:

If they be two, they are two so

As stiff twin compasses are two,

Thy soul the fixed foot, makes no show

To move, but doth, if the other doe.

And though it in the center sit,

Yet when the other far doth rome,

It leanes, and hearkens after it,

And grows erect, as that comes home.

Donne’s reputation as a poet suffered many vicissitudes after his death. For more than a generation he remained the chief mflence on English lyric poetry, but with the coming of neoclassicism his vogue began to wane. A succession of important English poets, however, honored his memory, although with reservations. Dryden admired his wit but was troubled by his flouting of decorum; Pope found him worthy of imitation; Dr. Johnson esteemed his learning but censured him for what he felt was a lack of taste. In the 19th century Coleridge praised him, and Donne is probably to be regarded as one of Browning’s sources for his conception of the dramatic monologue. The rehabilitation of Donne’s poetic reputation was completed in the 20th century.

Love Poems:

Donne’s love lyrics, or Songs and Sonnets, are strikingly original and among the most widely read of his works. Such poems as The Good-Morrow, The Canonization and Lovers Infiniteness depart from the conventions of Elizabethan love poets like Spenser, Sidney, and Drayton in a number of significant ways. Donne’s love poems are dramatic rather than descriptive: instead of delineating the beauties of his beloved or recounting the pangs of his desire, he characteristically speaks directly to his beloved, to some other individual, or to himself.

Donne is perhaps the greatest of English love poets. His eminence in this field rests not only on the intensity of his expression and the completeness with which he explores the entire range of amorous experience and its manifold moods but also on the nobility of his conception of sexual love. This conception, derived from Plato and influenced by Petrarch, departs from its sources in refusing to separate spiritual love from the bodily love in which, for Donne, it is rooted. His attitude is summed up in The Extasie, his most sustained presentation of an amorous philosophy.

The “Anniversaries.”

Donne’s interest in Copernican astronomy shows itself in the two Anniversaries (1611, 1612), the only important poetic works to see print during his lifetime. The 14-year-old daughter of Sir Robert Drury died in December 1610, and in the next year Donne published The First Anniversary: An Anatomy of the World, accompanied by A Funeral Elegie. The Second Anniversary: Of the Progress of the Soule appeared in 1612.

In these bizarre but very great works, the dead little girl is identified with some kind of vital female principle, the destruction of which means nothing less than the death of the world. In The First Anniversary the disturbing implications of the new science (Copernican-ism), with its abolition of the orderly world view inherited from previous ages, are adduced to symbolize the decay of the Creation. In The Second Anniversary, Donne’s obsessive theme of transcendence finds eloquent expression as he visualizes the soul of the dead girl, identified with the human soul in general, rising beyond all earthly concerns to experience the bliss of union with God.

Devotional Poems:

Among the poems written after Donne’s ordination, the most important are the three great Hymnes, three additional Holy Sonnets found in the Westmoreland Manuscript, which the critic Edmund Gosse purchased from the estate of the Earl of Westmoreland in 1892, and, possibly, A Nocturnall upon St. Lucy’s Day, Being the Shortest Day. The last-mentioned poem, one of the most complex and powerful of the Songs and Sonnets, is believed by some scholars to- have as its subject the death of the poet’s wife in 1617. Of the Westmoreland verses (which may be dated after 1617), one poem betrays continuing uncertainty about the nature of the true church and another poem contrasts the poet’s desperate love for his dead wife with the absolute love of God that he is trying to achieve. A similar concern announces itself in the earliest of the Hymnes, A Hymn to Christ at the Author’s Last Going into Germany, in which, with a characteristically imperative violence, the poet urges God to compel him to love Him alone.

There is some uncertainty concerning the dates of the composition of Donne’s last two great poems. A Hymn to God the Father, in which, typically, the poet puns on his own name, was probably occasioned by the same illness that elicited the prose Devotions. According to Izaak Walton, Donne’s earliest biographer, the Hymn to God my God, in my Sickness was composed by Donne on his deathbed, but some modern scholars believe it to be contemporaneous with the Hymn to God the Father and identical in inspiration.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the Hymn to God, my God, in my Sickness is reminiscent of Donne’s religious prose in its sobriety of tone and singleness of purpose. The poem recalls both the Holy Sonnets and the more passionate of the Songs and Sonnets in its combination of emotional intensity and ingenious and playful wit. Its exploitation of the imagery of geography and exploration reminds the reader of such amorous poems as The Good-Morrow and The Sunne Rising. And its last line, a characteristic theological paradox, sums up the tortured complexity of Donne’s personality and of the vision his works express: “Therefore that He may raise the Lord throws down.”

Source : wikipedia.org

Prose:

Donne’s middle years saw the production of a wide variety of works. In addition to the two meditative sequences of Holy Sonnets, he wrote many verse letters, witty and often obscure, addressed usually to fellow intellectuals or to his courtly patronesses. Some time around 1608 he wrote Biathanatos, a prose tract attempting to prove that suicide “is not so naturally a sinne, that it may never be otherwise.” This work, an indication of the writer’s distress at that time, was not published until 1646. Pseudo-Martyr, a learned treatise arguing the Anglican position against the Roman Catholic, was published in 1610, and in the next year appeared Ignatius His Conclave, a hilarious prose satire against the Jesuits. A minor theme of Ignatius is Donne’s interest in the new heliocentric astronomy espoused originally by Copernicus and supported in Donne’s own day by the findings of Kepler and Galileo.

After his ordination Donne devoted himself largely to religious writings, for the most part in prose. His more than 160 sermons, published in great folio editions in 1640, 1649, and 1660, constitute an extraordinary body of prose. Related to his poetry by their qualities of imagination, extravagance, and wit, Donne’s Sermons recall the poems also in their characteristic themes and emphasis. Unusual in an age of virulent religious controversy by virtue of their broad viewpoint and moderate tone, they concentrate on the essentials of Christianity rather than on controversial points of dogma. A recurrent theme is divine love; another, typically Donnesque, is the inevitable death and dissolution of the body, on the details of which Donne’s imagination dwells with disturbing power. He shows no contempt for the body, however; and the vision of physical decay is consistently balanced by his dwelling on the doctrine of the resurrection of the body, destined, for those who are saved, to be glorified and reunited with the soul. Donne the preacher is the same man who, years before, had written The Extasie.

Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, published in 1624, ranks with the Sermons in assuring Donne’s immortality among writers of English prose. In 1623, Donne suffered a near fatal illness; the Devotions are the psychological and spiritual fruit of that attack and his recovery from it. In a series of 23 units, each consisting of a “Meditation,” an “Expostulation,” and a “Prayer,” Donne traces the various steps of his disease and its cure, expanding his full imaginative energy on drawing witty analogies between the situation of man in sickness and the general situation of man in his sinfulness and his need for divine mercy.

A prominent example of the general European spiritual practice of formal meditation, the Devotions are notable for their psychological perceptions, powerful expression of the theme of brotherhood, and demonstration of the rhetorical strength of baroque prose—a kind of prose that, eschewing the more formal style and structure of typical Renaissance works, aims at achieving dramatic and colloquial immediacy. Donne’s prose, like that of other prominent prose-writers of the time, suggests not the polished and persuasive presentation of conclusions arrived at some time in the past, but rather the illusion of thought in the very process of being thought.