Learn about Jay’s Treaty, a diplomatic agreement signed between the United States and Great Britain in 1794. Discover the background and context of the treaty, the terms that were negotiated, and the controversy surrounding its ratification.

Jay’s Treaty Significance and Summary

Jay’s Treaty, also known as the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, was a diplomatic agreement signed between the United States and Great Britain on November 19, 1794. The treaty was negotiated by John Jay, the Chief Justice of the United States, and it aimed to resolve several outstanding issues between the two countries after the American Revolutionary War.

Under the terms of the treaty, Great Britain agreed to evacuate its forts in the Northwest Territory, which it had occupied in violation of the Treaty of Paris that ended the war. The treaty also established a commission to resolve issues related to British seizures of American ships and cargo, and it granted American merchants the right to trade with British colonies in the Caribbean.

In exchange, the United States agreed to compensate British merchants for losses they had suffered during the war, and to restrict American trade with France, which was then engaged in a conflict with Britain. The treaty was controversial at the time, with many Americans believing that it was too favorable to Great Britain and a betrayal of the country’s alliance with France. Despite this opposition, President George Washington ultimately supported the treaty, and it was ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1795.

Background:

Jay’s Treaty was signed in 1794, but its origins can be traced back to the American Revolutionary War, which lasted from 1775 to 1783. During the war, the United States, then known as the Thirteen Colonies, fought against Great Britain for its independence. After the war, the newly formed United States and Great Britain had a strained relationship, with many unresolved issues between the two countries.

One of the major issues was Great Britain’s refusal to evacuate its forts in the Northwest Territory, which had been ceded to the United States under the Treaty of Paris of 1783 that ended the war. In addition, British naval vessels were seizing American ships and cargo, and British merchants were seeking compensation for property seized or destroyed during the war.

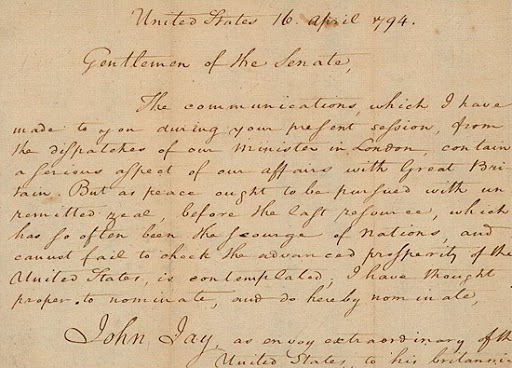

In an attempt to address these issues, President George Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London in 1794 to negotiate a treaty with Great Britain. Jay was an experienced diplomat and had previously served as the U.S. Minister to Spain. He negotiated the treaty with British Foreign Secretary Lord Grenville, and it was signed on November 19, 1794.

Terms:

The terms of Jay’s Treaty included:

- The evacuation of British troops from forts in the Northwest Territory, which had been ceded to the United States under the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

- The establishment of a commission to resolve issues related to British seizures of American ships and cargo, which had been a major point of contention between the two countries.

- The granting of American merchants the right to trade with British colonies in the Caribbean, which was a significant boon for American commerce.

- The agreement that American ships would no longer be seized by the British, and that the British would pay compensation to American merchants for ships and goods that had already been seized.

- The establishment of a boundary between the United States and British Canada in the Great Lakes region, which helped to reduce tensions between the two countries.

- The agreement that the United States would compensate British merchants for losses they had suffered during the war, which was a controversial provision of the treaty.

- The agreement that the United States would restrict trade with France, which was then engaged in a conflict with Britain. This was seen as a betrayal of the United States’ alliance with France, and was a major source of controversy surrounding the treaty.

Ratification:

Jay’s Treaty was a controversial agreement, and its ratification was not guaranteed. In the United States, there was a division between those who supported the treaty and those who opposed it.

The Federalist Party, which was then in power, supported the treaty and argued that it was necessary to avoid a potential war with Great Britain. The Anti-Federalist Party, which was in opposition, saw the treaty as too favorable to Britain and a betrayal of the United States’ alliance with France.

After the treaty was signed, it was sent to the U.S. Senate for ratification. The Senate debated the treaty extensively, and eventually ratified it on June 24, 1795, by a vote of 20-10. The ratification was not without controversy, as the opposition argued that the treaty was unconstitutional and went against the interests of the United States.

The ratification of Jay’s Treaty marked an important moment in the history of U.S. foreign policy. It helped to resolve many of the outstanding issues between the United States and Great Britain and paved the way for closer diplomatic relations between the two countries. However, it also highlighted the divisions within the United States over its role in the world and its relationships with other nations.