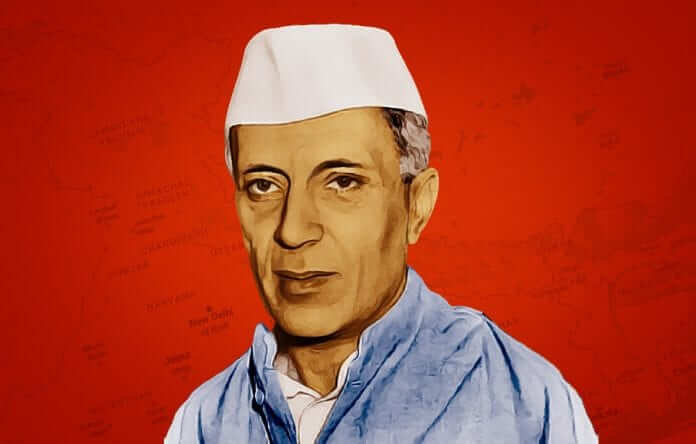

Who was Jawaharlal Nehru? What did Jawaharlal Nehru do for India? Information on Jawaharlal Nehru biography, detailed life story and career.

Jawaharlal Nehru; The first prime minister of independent India, Jawaharlal Nehru dedicated his life to seeking freedom for his people. He was one of Mohandas K. Gandhi’s chief lieutenants in the fight for independence from the 1920’s through the 1940’s. After independence had been won in 1947, Nehru served as prime minister for 17 years. His total span of national service was even longer than Gandhi’s.

Nehru’s identification with Gandhi’s politics began in 1919. From then on it was India’s good fortune that these two remarkable men worked side by side for more than a quarter of a century in the cause of Indian freedom. When Gandhi was assassinated a few months after independence, Nehru was left alone with the terrifying responsibility of guiding India through its first dangerous years of freedom.

Nehru will be remembered as the architect of modern India. By his magic grip on the people, he was able to push through progressive ideas and reforms that another leader might have found difficult to achieve. As prime minister he gave the government the stamp of his highly individual personality. He imbued India with a democratic spirit, and gave it a framework of unity. He inspired a spirit of secularism that removed traditional religious influences from government affairs, and he set economic goals to help the people escape from poverty. In international affairs, he projected the image of India as a developing but ancient country that had positive contributions to make to world understanding.

Early Life

Boyhood.

Nehru was born on Nov. 14, 1889, at Allahabad, India. His name Jawaharlal mea»s “red jewel,” a name he once said he found “odious.” His father, Motilal Nehru, was a wealthy lawyer from the state of Kashmir. Both he and Nehru’s mother, Swarup Bani Nehru, were Brahmans, the highest caste in India. Jawaharlal had two younger sisters: Swarup, born in 1900, and Krishna, born in 1907. They grew up in a palatial home called Anand Bhawan, meaning Abode of Happiness.

India was a part of the British Empire, and many of Motilal’s friends were English. Until Nehru was 15, he was educated at home by British tutors. He also studied the Hindi and Sanskrit languages with a Brahman teacher who, according to Nehru, managed to impart “extraordinarily little.” The only one of his tutors who impressed the boy was a French-Irish philosopher named Ferdinand T. Brooks. Brooks imbued Jawaharlal with an enthusiasm for reading and for science.

He introduced the youth to theosophy, a mystical system of thought that claims to explain the universe on the basis of direct revelations. The doctrine fascinated Nehru, and at the age of 13 he joined the theosophical society. But his interest in theosophy soon waned.

Student in England. In 1905, Nehru’s father took him to England to enroll at Harrow, a leading English public school. Nehru’s housemaster, the Bev. Edgar Stogdon, remembered him later as “a very nice boy, quiet and very refined. He was not demonstrative but one felt there was great strength of character. I should doubt if he told many boys what his opinions were. . . .”

Jawaharlal entered Trinity College at Cambridge University in 1907. There he studied chemistry, geology, and botany. He displayed little intellectual interest or ambition. He attended meetings of a debating society, but seldom found courage to speak himself. Nonetheless, the society’s political discussions stirred his interest in the growing Indian nationalist movement. He also became sensitive to discrimination against Indians. After completing his studies at Cambridge University, Nehru studied law in London, where he passed his bar examination in 1912.

Nationalist Leader

When the 22-year-old Nehru returned to India in 1912, a haze of political apathy had settled over the country. The British were firmly in control of the government. Among the Indian people, political power was held largely by the moderate leaders of the Indian National Congress party. But the Congress party was concerned primarily with reform, not freedom. Not until later did the Congress assume leadership in the independence movement.

For several years Nehru took only a desultory interest in politics, remaining for the most part an uneasy spectator of events. He concentrated at first on the practice of law, and paid little attention to the squalor and poverty of the Indian masses.

Marriage.

In March, 1916, Nehru married 17-year-old Kamala Kaul, the daughter of a Kashmiri businessman. Nehru’s bride was chosen by his father, because at that time love marriages in the tradition of the West were not common in India. Kamala was tall and shy. Though healthy in appearance, she was not physically strong. While Kamala was not an intellectual like her husband, she strengthened him with her understanding and her devotion to his principles. They had one child, a daughter, Priyadarshhani Indira (later Mrs. Feroze Gandhi).

Gandhi’s Disciple.

Nehru met Mohandas K. Gandhi for the first time at a session of the Congress party in Lucknow in 1916. They apparently did not make any considerable impression on each other at that time. Describing this first meeting, Nehru wrote: “All of us admired him for his heroic fight in South Africa [against discrimination toward Indians]but he seemed very distant and different and unpolitical to many of us young men.”

A devout Hindu, Gandhi did not believe in violence. He contended that swaraj (freedom) could be attained by adopting an attitude of nonviolent noncooperation toward the British. The 30 years preceding independence were marked by much violence, and Gandhi repeatedly pleaded with some of his younger and less patient followers—including Nehru—to exercise restraint.

Nehru and his father Motilal joined Gandhi actively after the Jalianwallah Bagh massacre of April, 1919. This tragedy occurred when British Gen. Reginald Dyer ordered his troops to fire on several thousand unarmed Indians who had gathered in the city of Amritsar against the orders of the authorities. Officials estimated that 379 Indians were killed and 1,200 wounded.

A year later Nehru first came in close touch with India’s peasantry when he visited a settlement on the banks of the Jumna River at Allahabad in May, 1920. He stayed for three days. “That visit was a revelation to me,” he wrote later. “Looking at them and their misery and overflowing gratitude, I was filled with shame and sorrow, shame at my own easy-going and comfortable life and our petty politics of the city which ignored this vast multitude of seminaked sons and daughters of India, sorrow at the degradation and overwhelming poverty of India. A new picture of India seemed to rise before me, naked, starving, crushed and utterly miserable. And their faith in us, casual visitors from the distant city, embarrassed me and filled me with a new responsibility that frightened me.”

Henceforth, Nehru saw India largely in terms of the oppressed peasantry. In order to give their full attention to the struggle for freedom, both Motilal and Jawaharlal gave up their legal practice. Motilal discharged his servants and sold his carriages and horses. The women in the family donned homespun saris in place of silks and brocades. Motilal secretly slept on the floor to find out what living in jail might be like. Jawaharlal willingly accepted austerity, and found it to be a bond between himself and the masses. His wife Kamala had found it difficult to adjust to Western standards of living when she married Nehru. Now she demonstrated real strength of character by accepting austerity with grace. Jawaharlal began to take a much more active part in Congress party politics.

In December, 1921, Nehru was arrested for distributing notices calling for a temporary suspension of all business as a demonstration against the British authorities. He was imprisoned for three months before the authorities decided that his action had been legal.

Travels in the West.

In the autumn of 1925, Nehru’s wife fell seriously ill from tuberculosis, and he decided to take her to Europe for treatment. Visiting Europe for the first time in 14 years, Nehru was deeply influenced during the 21 months he stayed there. His trip enabled him to graft onto his awakened nationalism a new sense of internationalism. He came to view India not in isolation but as part of a world community. Nehru met a number of European liberals and intellectuals, and his conversations with them inclined him toward socialism.

He visited Moscow, and was impressed by the will and the effort of the Russian communists to build a prosperous and classless society. The Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 had signified to Nehru, as it did to many Asians of his generation, the overthrow of tyranny by men who were also dedicated to the freeing of oppressed colonial peoples and to the economic improvement of the underprivileged. If India did not embrace communism as the most effective counter to British imperialism, it was because of the magnetism of Gandhi, who filled the Indian atmosphere with a specifically Indian vision.

Leader in the Fight for Freedom. Upon his return in 1927, Nehru found India stirring with new political life. He resumed his active role in politics, as secretary of the Congress party, a post he held before his European trip. But his speeches now revealed a new radicalism, and a rebellion against the caution of older leaders. “You are going too fast,” Gandhi wrote in 1928. “I do not know whether you still believe in an unadulterated non-violence. But even if you have altered your views, you could not think that unlicensed and unbridled violence is going to deliver the country.”

Even during their period of disagreement, however, the men retained a high regard for each other. In 1929, Gandhi endorsed Nehru for president of the Congress party, contending that more of the fight for independence must be borne by younger men. Nehru was elected, and presided for the first time at the Congress session that adopted independence as the party’s goal.

In his presidential address Nehru declared: “I must frankly confess that I am a socialist and a republican, and am no believer in kings and princes, or in the order which produces the modern kings of industry who have greater power over the lives and fortunes of men than even the kings of old, and whose methods are as predatory as those of the feudal aristocracy.”

In 1930, Gandhi launched his celebrated campaign of civil disobedience, during which Nehru was imprisoned. While in prison, Nehru learned that Kamala, despite her frail health, was helping to organize the civil disobedience movement in Allahabad. His wife’s will and energy made him proud and amazed. Years later Nehru wrote: “She wanted to play her own part in the national struggle and not be merely a hanger-on and a shadow of her husband. She wanted to justify herself to her own self as well as to the world. Nothing in the world could have pleased me more than this, but I was far too busy to see beneath the surface and I was blind to what she looked for and so ardently desired.”

Nehru’s father, Motilal, died in 1931, and thereafter Nehru moved in Gandhi’s inner circle. As the 1930’s progressed, both Gandhi and Nehru were jailed for civil disobedience. In all, Nehru was imprisoned nine times in the cause of India’s independence, serving a total of nine years in jail from 1921 to 1945.

In 1936, Kamala died. Nehru’s autobiography, which he had written in prison, was then in the hands of his publishers in London. He cabled a dedication to be included in the book: “To Kamala who is no more.”

Another Visit to Europe.

Nehru returned to Europe for six months in 1938. This visit coincided with the Anglo-French betrayal of the Czechs at Munich. On this visit, Nehru was equally irked by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s equivocal attitude toward Nazism, and by the British Labour party’s lukewarm support for Indian independence. Ironically, he was then against appeasement and very definitely for taking sides against Hitler. His policy of non-alignment was some years away.

Nehru’s 1926 and 1938 visits to Europe, separated by more than a decade, were landmarks in the development of his thinking. He was a parlor socialist when he visited Europe in 1926, but was not clear about the means to be adopted to improve the Indian economy. Between his two visits, particularly during his many terms in prison in the early 1930’s, Nehru had spent much of his time reading socialist and communist literature. When he went to Europe again in 1938, his views on many important political and economic matters had crystallized. They generally remained unchanged for the rest of his life. Nehru saw the Western world from within the blinkers of the 1930’s—economically in terms of the socialist theories of the British Labour party, and politically in the image of Western imperialism, which he believed was a natural consequence of capitalism. Though the violence of communism repelled him and though he detected in it the overtones of dictatorship, he was always reluctant to associate communism with colonialism—even after the Chinese communists overran Tibet in 1951 and after the Hungarian Revolution against the Russians in 1956. To him colonialism was a by-product of capitalism, not of socialism as Marx interpreted it.

In a very real and tragic sense, Nehru’s was a case of arrested economic and political thinking. It is extraordinary how little his outlook in the last decade of his life differed from the views he expressed in his autobiography published in the mid-1930’s.

World War II.

In 1939, when World War II began, Nehru cut short a visit to China. Relations between the Congress party and the British government deteriorated sharply. In the fall of 1940, Nehru was arrested and jailed again after speaking out against the British war effort. He was released on Dec. 4, 1941, along with many other political prisoners.

In August, 1942, the All-India Congress Committee meeting in Bombay demanded that the British leave India at once, and pledged that a free India would join the Allies. Immediately, Gandhi and Nehru were arrested and detained at a fort in Ahmadnagar. This was Nehru’s last and longest term of imprisonment, a term from which he was not freed until June 15, 1945, just before the war ended.

First Prime Minister of India

In July, 1945, a month after Nehru’s release from prison, the Labour party came to power in Britain. Its leaders had pledged to grant dominion status to India. In the months that followed, the British granted India greater self-rule; and in September, 1946, the British viceroy invited Nehru, who was once again president of the Congress party, to form an interim government.

Independence. The last big roadblock to independence was the revolt against the Congress leadership by the Moslem leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah. He called not only for liberation from Britain, but also for the partition of the Indian Empire into separate Hindu and Moslem states. Talks between Hindu and Moslem leaders reached an impasse in 1947. Then the British government announced that it would withdraw from India by June, 1948, whether or not an agreement had been reached. In the face of this ultimatum, Nehru and Gandhi reluctantly consented to the creation of the separate Islamic state of Pakistan. The Indian Independence Act was passed by the British parliament in July, 1947.

On Aug. 15, 1947, India moved from foreign rule to freedom, with the 57-year-old Jawaharlal Nehru as the first prime minister of the Dominión of India.

With the coming of independence, India was engulfed in many problems. The partition of the subcontinent into two nations brought a stream of some 9 million Hindu refugees from East and West Pakistan, while more than 4 million Moslems migrated to Pakistan from India. The first task of the Nehru government was to rehabilitate these refugees and absorb them into their new surroundings. At the same time, riots between Hindus and Moslems resulted in thousands of deaths, and culminated in the assassination of Gandhi by a Hindu fanatic. Some 550 princely states were given the option of joining either India or Pakistan. Nehru integrated all these states into India except Kashmir, which remained in dispute between India and Pakistan.

India was proclaimed a republic under a new constitution in 1950. Nehru again was elected prime minister, a position he held the rest of his life. Although he previously favored full independence for India and withdrawal from the British empire, Nehru courageously decided that India should remain within the British Commonwealth. In 1948 he attended the first Commonwealth prime ministers’ conference in London, and at the time of his death in 1964 he was the elder statesman of the Commonwealth.

Shaping a New India.

Nehru’s most positive contribution to India was his insistence that India remain a democracy wedded to secular ideals. He worked strenuously to preserve the unity of India as a political democracy and a planned welfare state. He held that the socialistic pattern of India should be achieved not by coercion but by a process of free discussion.

Nehru appointed a government planning commission in March 1950, and he presided over this body until his death. The First Five-Year Plan came into operation on April 1, 1951. Despite the plan, economic development was slow, and the Third Five-Year Plan was lagging far behind its target at the time of Nehru’s death. On the whole, however, the plans laid the foundation for faster economic development.

As part of his program to make India more progressive, Nehru attempted to root out injustice in the social system. The Untouchability Act of 1955 provided penalties to enforce provisions of the Constitution that oudawed the practice of untouchability in the caste system of India. In 1956 widows were given the right of inheritance in family property. Bigamy was forbidden. The forced marches out of poverty and social backwardness initiated by Nehru brought about a radical social and economic revolution.

Foreign Affairs.

Under Nehru’s guidance, India adopted a policy of nonalignment—a basic principle deriving from his conviction that the economic progress of India could be, achieved only in a peaceful world. He was criticized not so much for the policy itself as for the manner in which he appeared to implement it. It was felt that he was guilty of applying a dual standard of judgment that inclined more toward the communist bloc than toward the West. Nehru drew considerable criticism in 1956 when he unequivocally denounced the Anglo-French action in the Suez War against Egypt but directed only a mild rebuke at Russia for its brutality in crushing the Hungarian Revolution. He seemed, however, to have learned from that incident, and after 1956 he followed a more dispassionate policy.

Nehru’s greatest disappointment was his failure to achieve peaceful coexistence with communist China. He went very much out of his way to conciliate Peking, and in the process he incited criticism both abroad and at home. Although the Chinese incursions into India’s northern border began soon after the signing of the Sino-Indian Treaty on Tibet in April 1954, Nehru did not reveal these incursions and infiltrations to the Indian parliament until late in 1959. The revelations created an uproar, followed by a period of rapid disillusionment that culminated when the Chinese attacked in 1962 on the Sino-Indian frontier. The rapidity of the Chinese advance shocked Indian opinion, which grew doubly critical of Nehru. The unilateral cease-fire declared by the Chinese did not abate this criticism.

Last Days.

Nehru’s image was badly dented by the confrontation with communist China. But he continued, despite this, to command the love and affection of the Indian masses. His health began to deteriorate in 1962. After a stroke during a session of the Congress party in January, 1964, it was clear that Nehru did not have long to live. On May 27, 1964, he died at New Delhi at the age of 74.

mavi