Who was Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev? Information on author Ivan Turgenev biography, life story, works, books and poems.

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev; Russian author: b. Orel, Russia, Nov. 9 (Old Style Oct. 28), 1818; d. Bougival, near Paris, France, Sept. 3 (Old Style Aug. 22), 1883. His father was a retired cavalry officer who died in 1834; his mother, née Lutovina, was a rich landowner, whose despotic treatment of her serfs—and her children—left a deep impression on her son. Until he entered Moscow University, he was educated mostly by private tutors. After a year at Moscow, he transferred to St. Petersburg University, graduating in 1837. In 1838-1840 he studied philosophy in Berlin, planning an academic career; and there, as he said later, he became a “Westerner” for life.

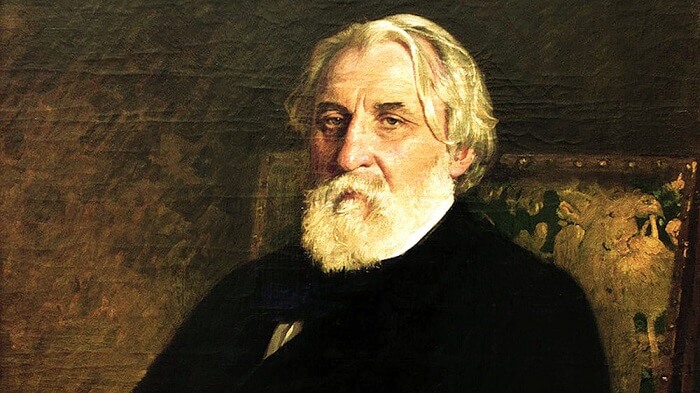

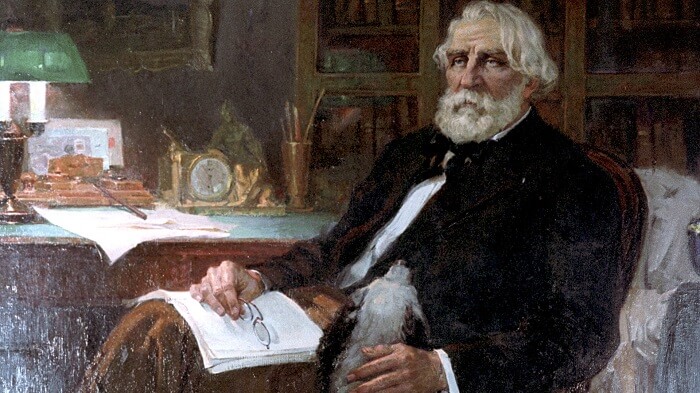

Ivan Turgenev

Turgenev began his literary career as a poet in the tradition of Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin and Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov, attracting attention with his narrative poems Parasha (1843) and Andrei (1845). He also experimented with the drama before finally settling on prose fiction as the form best suited to his talents. His most notable play is Mesyats v derevne (written 1850, published 1855; A Month in the Country), which Turgenev professed to believe unsuited for the stage. It was not produced until 1872. In 1843 he met the singer Pauline Viardot-Garcia, for whom he subsequently formed a lifelong attachment, spending much of his time abroad in order to be near her. His mother tried to force his return by depriving him of money, but her death in 1850 left him financially independent.

Turgenev’s literary fame dates from 1847-1852, when his Zapiski okhotnika ( Notes of a Hunter; A Sportsman’s Sketches) were appearing in the periodical Sovremennik (The Contemporary). They depict rural life in the 1840’s from the point of view of a sensitive young squire, alienated from and hostile to his own class, who discovers among the peasants unexpected resources of intelligence, artistic talent, and emotional refinement, only partially stifled or warped by conditions of serfdom. They are written in Turgenev’s best style, simple, precise, yet with great power to evoke emotional subtleties. The government, however, became alarmed when they appeared in book form in 1852, and banished Turgenev to his estate, ostensibly for an overenthusiastic obituary on Nikolai Vasiliyevich Gogol. He was released the following year.

With the accession of Alexander II (1855), Turgenev became a leading spokesman for the liberal aspirations of the new reign.

He began a series of novels designed as commentaries in artistic form on current social and moral problems. Rudin (1856) presents the tragic dilemma of the philosophizing intellectual “Westerner” of Turgenev’s generation, generous in impulse but incapable of effective action. Dvoryanskoye gnezdo (1859; A Nest of Gentlefolk; Liza), the most Slavophile of Turgenev’s works, gives a retrospectively nostalgic view of the life of the old gentry. In the less successful Nakanune (1860; On the Eve), Turgenev, apparently unable to discover a Russian activist, takes a Bulgarian patriot as his hero and bestows upon him one of his dedicated and purehearted Russian girls.

Ottsy i deti (1862; Fathers and Children; Fathers and Sons), the greatest of Turgenev’s novels, treats the conflict between the “soft” aesthetic idealists of the older generation and the “hard” plebeian radicals of the 1860’s. In all these novels the topical themes are more or less successfully integrated with a love story, utilized both as a plot framework and as a touchstone of character. Other stories and short novels of this period lack the topical concerns of the novels; though less well known, they are often more satisfactory artistically. Among them are Faust (1856), Asya (written 1857, published 1858), and Pervaya lyubov (I860; First Love).

Fathers and Sons set off a violent critical controversy. All educated Russians had to take sides, for or against its “nihilist” hero Bazarov. The conservatives censured Turgenev for flattering the radical youth; the radicals were divided, one group accusing Turgenev of slander, the other wholeheartedly accepting Bazarov’s “nihilist” code of uncompromising materialism and utilitarianism. Turgenev, feeling hurt and misunderstood, affected to renounce literature and Russia forever. These feelings were expressed in the prose elegy Dovolno (written 1864, published 1865; Enough), later mercilessly parodied by Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky in The Possessed.

In 1863, Turgenev settled permanently in Baden-Baden. He counterattacked both radicals and conservatives in the novel Dym (1867; Smoke), reiterating his belief that Russia’s only salvation lay in the gradual assimilation of Western civilization. This ideological message is loosely linked with a typical Turgenevesque love story, contrasting two recurrent female types, the strong, pure, devoted girl, and the sensual, rapacious married woman; his passive hero vacillates between them. In 1870 the Franco-Prussian War forced the Viar-dots and Turgenev to leave Germany for Paris, where he remained, except for short visits to Russia, until his death. He became prominent in the French literary world, friendly with Gustave Flaubert, fimile Zola, and others, and did a great deal to introduce Russian literature in Europe.

The literary work of Turgenev’s late years is uneven in character and quality. He attempted one more topical novel, Nov (1877; Virgin Soil), which dealt critically with the “going to the people” movement of the early 1870’s. Partly because he knew his material only at second hand, it is one of his least effective novels. He wrote more retrospective fiction about the Russia of his youth; Stepnoi Korol Lir (1870; A Lear of the Steppes), Veshniye vody (written 1871, published 1872; Torrents of Spring), and Punin and Baburin (1874) are among his best stories. He also produced a series of stories on supernatural themes, among them Pesn torzhestmiyushchei lyubvi (1881; The Song of Triumphant Love) and Klara Milich (written 1882, published 1883).

His last work was Stikhotvoreniya v proze (1878-1882; Poems in Prose), an attempt to express in the form of lyric fragments the pessimism of his old age, his conviction of the transitoriness and futility of all human things. Although he was more celebrated than Leo Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky in his lifetime, Turgenev’s reputation since his death has been somewhat eclipsed by theirs. Nevertheless he remains one of the major Russian classics.