What are the features and examples of Byzantine Art? Detailed information about Byzantine art, architecture, mosaics, manuscript, ivories, etc

BYZANTINE ART AND ARCHITECTURE, flourished for more than 1,000 years—from 330 a.d. to about 1400—in the Byzantine, or Eastern Roman, Empire.

Diocletian, who ruled the Roman Empire from 284 to 305, first divided its vast territories into eastern and western sections for administrative purposes. In 330, Constantine moved the capital of the empire to the eastern city of Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople (now Istanbul). While Rome “in the West tottered to its fall, the Eastern, or Byzantine, Empire waxed in power, reaching its climax under Justinian, who reigned from 527 to 565. His able generals, Belisarius and Narses, added North Africa, Sicily, and the eastern Gothic kingdom around Ravenna in northern Italy to the already great Byzantine domain.

Source : wikipedia.org

Since most secular Byzantine buildings have been destroyed, the characteristics of Byzantine style are best studied in the churches that constitute the major surviving monuments of the Empire. The churches are generally dominated by a brick dome, which is often combined with one or more subsidiary domes arranged in various ways. A dome emphasizes and defines the space beneath it, and, when combined with other vaults, it creates a rich spatial organization within the building.

The liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church and its allied churches requires a screen, or iconostasis, to separate the chancel from the space for the laity beneath the principal dome. The chancel is flanked by the prosthesis, where the elements of the Eucharist are prepared, and by the diaconicon, or vestry. The exterior of Byzantine churches, at least for the first few centuries, was drab. But colored marble columns, slabs of similar material on the lower walls, and mosaics, often with gold backgrounds, made the interior resplendent.

Scholars have long debated the origins of Byzantine style. One group maintains that its sources must be sought in the eastern Mediterranean area, in Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Anatolia, or even farther into Asia. In support of their thesis they point to such qualities as the luxuriant use of color common to Middle Eastern and Byzantine architecture.

Other authorities, with perhaps stronger evidence, trace the roots of Byzantine style to Rome. These scholars cite the unencumbered interior space of Byzantine structures, which is unlike the older styles of the Middle East but similar to the spatial organization originally developed in imperial Roman architecture and carried with the expansion of the empire to most of the Middle East. Rome also produced the first great style of vaulted architecture, which eastern Mediterranean cultures had studiously avoided on a large scale for important buildings. The Byzantine brick dome lighted by windows around the perimeter, also harks back to Roman precedents, as in the domes of the caldarium in the Baths of Caracalla (211-217) and of the Temple of Minerva Medica (310-320), both in Rome.

Source : wikipedia.org

Other characteristics of Byzantine architecture that can be traced to Roman sources are the squinch and the pendentive, both devices to support a circular dome on a square plan. A squinch is a flat slab, arch, or arched niche built over the corner of a square structure to convert that shape into an octagon. One of the earliest examples of the squinch is found in the Villa of Hadrian (125-135) at Tivoli.

More important in Byzantine architecture than the squinch is the pendentive, which in fact became the outstanding feature of the Byzantine style. The pendentive is a segment of a hemisphere which has a diameter equal to the diagonal of the square to be covered. In less technical terms, it is a vaulted spherical triangle, whose lower apex rests upon a pier and whose curved upper surface, combined with three other pendentives, provides the circular support on which the dome can be built. Pendentives on a small scale first appear in Roman tombs of the 1st or 2d century and in large sizes in the later Baths of Caracalla.

Early Roman architecture adopted the classic Greek relationships between the column, its support, and what it carried. During the 3d and 4th centuries, however, Roman architecture began to abandon these classical orders of architecture. In the Palace of Diocletian (about 300) at Spalato (Split), arches rest directly on the column capitals, the architrave is bent into the arched form known as an archivolt, and other violations of the rules of the orders are common. This freedom in handling the orders later became typical of Byzantine architecture. The Byzantine use of colored marbles (rarely, if ever, used in eastern Mediterranean countries prior to Roman occupation) has its precedents in the marble floors and sheathing on the lower walls of Roman buildings, such as the Palace of Domitian (about 90), the Baths of Diocletian (305), and the Basilica of Constantine (306-312), all in Rome.

Byzantine architecture, despite its Roman roots, had developed a distinctive character of its own by the 6th century. The same may be said of Byzantine mosaics, manuscripts, and ivories. Roman sculpture in the 4th century abandoned the lifelike realism of earlier Roman art, producing figures that are puppetlike, with naive modifications of normal body proportions. From this source Byzantine mosaic workers and carvers of ivory had developed by the 6th century a highly sophisticated style. A hieratic and courtly elegance found expression in stylized linear figures with sumptuous details of costume that reflect the semioriental luxury of Justinian’s reign.

The First Golden Age.

The first flowering of the Byzantine style took place under Justinian in the 6th century. A distinctly Byzantine style had evolved by this time, not only in architecture but in mosaics, manuscripts, and ivory carving.

Source : wikipedia.org

Architecture.

During the First Golden Age, architecture continued to use the basilican plan with its plain timber roof and colonnades dividing the nave from the side aisles. Examples such as Sant’Apollinare in Classe (534-538) and Sant’Apollinare Nuovo (about 500), both in Ravenna, also make use of the typically Byzantine dosseret, a block above the capital that supports the arches and concentrates their weight on the capitals. The first clear structural example of the use of the dosseret is in the Basilica Ursiana (370-384), Bavenna, an otherwise Roman building. The dosserets, coupled with the spiny acanthus motif in the capitals and the gorgeous mosaics, give to the Ravenna churches a decidedly Byzantine flavor.

Even more Byzantine in style is San Vitale, Ravenna, which was completed by Justinian in 547. The central dome rests on squinches, with columnar niches between seven of the eight piers and a vaulted chancel in the eighth. An octagonal aisle surrounds this complex. Windows in the drum light the central area. Colored marbles, mosaics, and the surface carving of the capitals and dosserets are purely Byzantine.

Charlemagne’s chapel (796-804) at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) is a much simpler and somewhat naive restudy of this church, but it lacks entirely the polychromy of its model.

Similar in plan to San Vitale is the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus (527-536), Constantinople. An octagon of piers and arches supports a dome whose shape is gored like the rind of a cantaloupe—a form that had a precedent in the Villa of Hadrian. The interior has been so modified as to obscure its Byzantine richness.

Hagia Eirene (St. Irene), Constantinople, which was rebuilt under Justinian but greatly altered since, has two domes over the nave—a hemispherical one with a row of windows around its base, and an elliptical one to the west of that. Thus domical forms were made to cover a longitudinal nave.

Source : wikipedia.org

The masterpiece of Byzantine architecture of the First Golden Age is Hagia Sophia (meaning “Divine Wisdom”; also called St. Sophia), in Constantinople. It was built under the patronage of Justinian, who, when the older basilican church was burned during the Nika Insurrection in 532, commissioned Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus to build a new church. It was completed in 537. It is almost certain that Anthemius had visited his brother, a noted physician in Rome, and there had mastered the principles of Roman architecture. Anthemius’ dome for Hagia Sophia fell after an earthquake in 558, but by 563 it had been replaced substantially in its present form by the younger Isidorus.

Hagia Sophia was preceded by an open court, or atrium, and entered through a double narthex, or vestibule. The church itself measures 308 feet by 236 feet (94 meters by 72 meters). The principal feature of Hagia Sophia, its dome, is about 102 feet (31 meters) in diameter. Such a vault presses outward in all directions, requiring massive support, which is provided in this case by broad arches to the north and south. Four huge piers, themselves buttressed by masses of masonry outside the building, hold the pendentives. Half-domes to the east and west, almost as large as the main dome, extend the length of the nave and help to about the main dome. These, in turn, are abutted by smaller half-domes over columnar niches. Colonnades between the piers separate the aisles and the galleries over them from the nave.

The Byzantine architects, following the precedent of early Christian basilicas, left the exterior with little or no decoration. However, the structural system of Hagia Sophia itself gives monu-mentality to the exterior of the building. The system of vaults, niches, buttresses, and half-domes leads up like waves to culminate in the main dome. Blocks of masonry between the windows of the dome weigh its; base like so many buttresses, leaving only the upper part of the dome’s curve apparent from the outside.

The builders of Hagia Sophia lavished their efforts on the interior of the building. Few churches were better lighted; great lunette windows pierce the curtain walls over the galleries to the north and south. Windows around the base of the dome flood it and the area below with light, visually reducing the solid appearance of the supports between the windows and creating the effect of a weightless dome suspended from above instead of supported from below.

Source : wikipedia.org

To this lightened impression the color scheme is ancillary. Red porphyry and verdant antique marble form the columns, while the walls up to the level of the capitals are sheathed in slabs of polychromed veined marble, cut so that the pattern of the veining is reversed in consecutive slabs. Dark blue color applied to the interstices of the patterns carved in capitals and moldings emphasizes the surface decoration by contrast to the white marble. These capitals adhere to none of the traditional orders of Roman architecture but are free designs of a cushion or basketlike shape. They may borrow the convex curve of the Doric echinus, the scroll forms, of the Ionic, and the leafage of the Corinthian order (now become the conventionalized spiny acanthus), but all are fused into something new and distinctly Byzantine. Above the level of the columns, the walls, arches, and vaults glitter with gold mosaic, carried around even the edges of intersecting planes. Small wonder then that Justinian prided himself on the building he had erected, and well might he exclaim, “I have surpassed thee, O Solomon!”

After the capture of Constantinople in 1453 by the Ottoman Turks, Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque. Some of its exterior surfaces were banded alternately light and dark, and four minarets were added at the corners. Hagia Sophia is now a museum.

Mosaics.

The medium of mosaic, in which figural or other designs are created from tesserae (small bits of colored marble or colored glass), was extensively practiced in Rome both for floors and for mural designs. The figures in Roman mosaics generally have some indication of three-dimensional solidity. In such early Christian basilicas as Santa Maria Maggiore (5th century), Rome, extensive scenes from the Scriptures appear in the wall mosaics. The mosaic in the apse of Santa Pudenziana (4th century), Rome, shows Christ enthroned, flanked by apostles. The figures, somewhat rounded, are clothed in plain robes; buildings and a clouded sky form the background.

Byzantine mosaic designers, however, were concerned with figures as symbols, rather than as actual human beings, and regarded the design primarily as a chance to use opulent decorative color. They made little use of shading or other indications of three-dimensionality.

Source : wikipedia.org

In the Byzantine Church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, the mosaic on one side above the arcade depicts a long file of male saints approaching Christ, and on the opposite wall a similar line of female saints headed by the three kings approaches the Virgin. The poses of the figures are nearly identical, as are their richly embroidered and jeweled costumes. There is little attempt to suggest roundness in the figures, and there is no setting except conventionalized palms between the figures. They form, however, a most effective decorative frieze, echoing the colonnade below and leading the eye to the sanctuary ahead.

Two celebrated mosaics face each other across the chancel of San Vitale, Ravenna. One shows the Emperor Justinian holding a patten, Archbishop Maximian with a small cross, priests carrying a book and a censer, and a group of courtiers. The opposite mosaic presents the Empress Theodora with a chalice, priests, and ladies of the court. The figures are almost frontal, in rich draperies at least for the rulers, and with the third dimension indicated more by linear folds than by shaded modeling. No setting is visible in the Justinian mosaic, but Theodora is seen against a shell-like niche with curtains at the sides. The heads have a degree the individuality uncommon in Byzantine mosaics. The Emperor and the Empress are distinguished by halos, used here as marks of rank, not of sanctity.

These mosaics lead up to the fine apse mosaic where Christ is seated on the globe flanked by angels and by San Vitale on one side and by Ecclesius, carrying a model of the church, on the other. The ground, like the draperies, is conventionalized, and the gold background, although laced with symbolic clouds, denies any sense of depth.

With the barbarian invasions of Italy and the west in the 5th century, Constantinople was the major beacon of civilization in Europe for the next two centuries, and Byzantine influence was felt even in Rome. For instance, the 7th century apse mosaic of Sant’Agnese outside the walls in Rome is formal, even rigid, in pose and costume. St. Agnes has become a Byzantine princess dressed in almost Oriental opulence, with a gold crown, gold and precious stones in her hair, a golden stole over her shoulders, and a violet tunic embroidered with gold.

Manuscripts.

The three most important Byzantine manuscripts of the late 5th or the 6th century are the Vienna Genesis (Imperial Library, Vienna), the Rossano Gospels (Cathedral of Rossano, Italy), and the Sinope Gospels (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris).

The Vienna Genesis is on purple vellum with silver lettering. The vivacious scenes, set at the bottom of each page, have many Byzantine details of costume and ceremony. Several successive events shown in a single picture preserve something of the “continuous narration” style, familiar from the relief on the Column of Trajan, Rome.

In the Rossano Gospels, also in silver on a purple ground, the miniatures may take a full page, or the top half of a page where the lower half is filled with four half-length figures. The figures are quieter and more dignified than those in the Vienna Genesis. The arrangement of the scenes, already standardized by the 5th century, persisted in Byzantine art for hundreds of years.

Source : wikipedia.org

The Sinope Gospels are written in gold on purple. Here the miniatures are at the bottom of the page, flanked by two half-length figures rising out of what might be pulpits. In this manuscript, perspective, atmosphere, and setting are avoided even more persistent than in the mosaics of San Vitale.

Ivories.

The most important surviving masterpiece of Byzantine ivory carving from the First Golden Age is the throne of Archbishop Maximian (mid-6th century) in the Cathedral of Ravenna. Its side panels have scenes from the life of Joseph in the narrative style. The Scythian or Sarmatian dress of Joseph’s guards indicate contact with Asia, as do the tiaras (like those of Persian kings) worn by the sons of Jacob. The Egyptian headdresses of the merchants, and the very choice of the story of Joseph, suggest Egyptian influence. Five panels on the front of the throne show St. John the Baptist and the four evangelists. The figures are stiff, and the drapery is conventionalized. The main scenes and figures are framed by vine patterns, within whose scrolls appear peacocks, deer, lions, and other decorative motifs.

Another masterpiece of Byzantine ivory carving is the panel of an archangel in the British Museum, probably from the 6th century, though dated by some scholars as 4th century. The figure stands on a flight of steps with a staff in his left hand and an orb in his right. The drapery, more classical than Byzantine, is conventionalized less than draperies carved in the throne of Maximian. But the decorative effect and some of the architectural details in the archangel panel are characteristically Byzantine.

Some of the best examples of Byzantine ivory carving are consular diptychs, two-leaved panels made for Roman consuls, usually to commemorate the achievements of their office. Examples survive from the Roman period until well into the 6th century. One leaf usually presents figures, a scene, or a decorative motif, such as a wreath with an inscription. The other leaf generally depicts the consul, who is shown standing in the earlier, Roman diptychs but seated in the diptychs of the Eastern Empire. A good example is the diptych of the consul Flavius Anastasius (517; South Kensington Museum, London), which has the formalized style and embroidered costume of the early Byzantine period.

Iconoclastic Age.

In 726 an edict of the Emperor Leo III forbade the representation of religious figures in churches and ordered the frescoed walls and mosaics to be whitewashed. The common people had come to attribute miraculous power to these images, a superstition that seemed to the emperor, and to many bishops for centuries before his time, a real menace to Christianity. Although Leo III did not enforce his edict very strictly, some of his 9th century successors were more rigid. Architecture was not directly affected, but for almost two centuries, iconoclasm eclipsed the representational arts of mosaic, fresco painting, and ivory carving. But the Iconoclasts, as the opponents of images were called, met vigorous opposition, particularly from the monks. The Empress Regent Theodora brought the iconoclastic period to an end in 842.

Source : wikipedia.org

The Macedonian Renaissance.

The Macedonian dynasty, which began with Basil I (reigned 867-886), gave Byzantine art and architecture a new lease on life. The art of Byzantium’s Second Golden Age, as it is sometimes called, had a far-reaching influence. Venice, by virtue of its strong trade connections with Constantinople, became a cultural offshoot of the Eastern Empire, and the Cathedral of St. Mark in Venice is one of the great masterpieces of the late Byzantine style.

Architecture.

The characteristic church plan of the late Byzantine period is a Greek cross whose four, almost equal arms are inscribed within a square. The plan had precedents in Roman tombs and in the 2d century Roman praetorium at Musmiyeh, Syria. Late Byzantine churches frequency have barrel vaults over the four arms of the cross and five domes, over the central crossing and in the four angles between the arms of the cross. The arrangement was quite logical structurally; the four barrel vaults abutted the central dome and were themselves abutted by the domes in the angles. Also during this period at least the central dome was usually raised above the rest of the building and given greater importance by the insertion of a masonry drum or cylinder. Eleventh century churches, such as St. Luke’s in Phocis, Greece, shows a growing concern with external appearance. Molded bands of decoration in stone or brick, some carving, and occasional use of color enrich these buildings. Few of these churches are large in scale; a charming vest-pocket edition is the Little Metropolitan Church (12th century) in Athens, with a dome that measures only 9 feet (2.7 meters) in diameter raised on a slender ornate drum.

The interiors of Byzantine churches of the 9th century and later are generally less impressive than those of earlier times. There is less dramatization of interior space, partly because of the smaller size of the buildings, partly because the cross-in-square plan broke up the interior, and partly because of the greater height of the buildings relative to their length and width. From inside the church these proportions give the viewer the impression that he is at the bottom of a space that extends vertically to the dome, but which is restricted horizontally.

The Basilica of St. Mark in Venice is the best-known example of later Byzantine architecture. It was rebuilt in the Byzantine style between 1063 and 1094. The Greek cross plan of St. Mark’s has five domes, but unlike its Byzantine contemporaries, four of these were placed over the arms of the cross instead of between them. The plan was borrowed from the Church of the Holy Apostles (6th century, now destroyed) in Constantinople. The exotic appearance of St. Mark’s today is the result of later additions. The domical constructions of wood and lead over the structural domes and much of the complicated detail, especially on the upper part of the building, were added during the Gothic period. But the lower part of the facade, with its multiple colonettes in colored marbles, and at least one of the mosaics above the doors are purely Byzantine, as is the whole interior. Most of the mosaics on the facade are Renaissance or modern in date, but the one farthest left as the viewer faces the church dates from the 13th century. It presents an illustration of St. Mark’s as it looked before the Gothic and later additions were made.

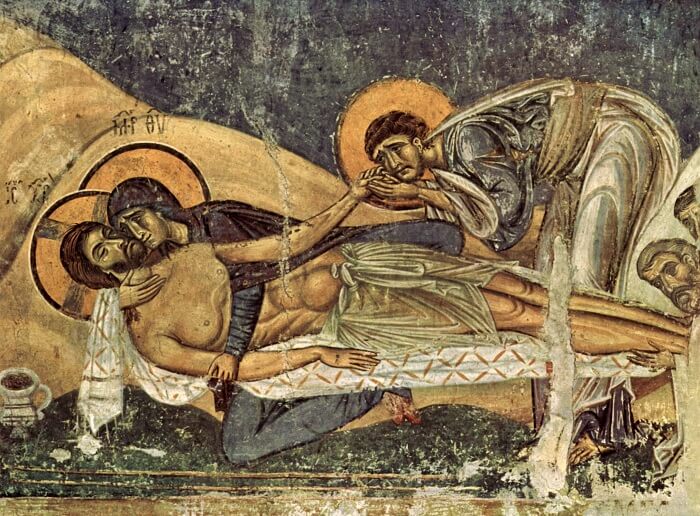

Mosaics and Frescoes.

The interior glory of these later Byzantine churches lies in their mosaics or in the frescoes sometimes substituted for the mosaics. The churches at Daphne and St. Luke’s, Phocis, are excellent examples. A fine, though much later (early 14th century) example of these decorations is St. Saviour in Chora (also called Kahriye Camii or Kariye Djami) in Constantinople.

The arrangement of subjects within the church was dictated by dogma and is therefore nearly the same in all late Byzantine churches. In the center of the main dome is Christ Pantocrator, the all-powerful judge and ruler of mankind, set within a ring of varied colors. Below Him the Virgin, St. John the Baptist, and angels are frequently represented, and below them the prophets. The evangelists generally fill the four main pendentives, serving as intermediaries between the heavenly figures above and the historical or Scriptural themes below. The Virgin and archangels occupy the half-dome of the apse, with Christ below them flanked by angels; beneath these is depicted the institution of the Eucharist and the fathers of the church. Also within the sanctuary may be Scriptural events or figures identified as prototypes of Christ. Elsewhere on the vaults and upper part of the walls in those areas of the church normally open to the laity are the twelve great festivals of the church, from the Annunciation through the Crucifixion and Resurrection, to the death of Mary. Below these may be shown miracles, events from the life of the Virgin, and figures of saints. Near the entrance to the church is pictured the Last Judgment.

Although some latitude was permitted, the general outline of this scheme was so standard that it was incorporated in handbooks for artists.

The purpose of the mosaic and fresco decorations was clearly didactic—to give visual reinforcement to the church year and church dogma. Nevertheless, the results at their best are magnificently decorative. The last traces of the Roman past have vanished from these highly stylized figures, which have almost no three-dimensional elements. On the contrary, draperies have become mere patterns of lines, such as concentric circles or ovals to suggest thighs or breasts. In proportion the figures tend to be more elongated than in earlier mosaics and frescoes. The colors were almost as rigidly dictated as the subjects, and a plain gold background denies any sense of space in most of the decorations.

Few buildings anywhere have a more richly colored interior than St. Mark’s with its polychromed marble floors, columns, and lower walls, and its mosaics that completely cover the upper walls and vaults, not only within the church itself but in the narthex, or vestibule. In the three domes of the nave and their supporting arches are mosaics from the 11th century; the narthex mosaics are mostly 13th century.

The major devotional panels in St. Mark’s, such as the one representing the Madonna flanked by two saints, are as hieratic and dignified as contemporary mosaics, manuscripts, and ivories from Constantinople. The Virgin and Christ Child are impersonal, distant creations, whose slender, curved fingers have become a linear formula. Below them are highly stylized allegorical figures of the virtues, with draperies that express the human body less than they resemble contour maps of hilly country. The inscriptions here are in Latin; in the churches of Constantinople they are in Greek.

Scenes from the life of Christ adorn the arches supporting the domes of the nave in St. Mark’s. These narrative panels are more animated though no more realistic in most respects than the other mosaics. One of the most lively panels illustrates the Resurrection; the risen Christ, trampling underfoot a grotesque figure of Satan, holds the cross in his left hand, while with his right hand he raises the kneeling Adam from hell.

Another panel illustrates Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. Christ’s steed walks over garments strewn in his path. Lines suggest the ground, while a palm tree and a conventionalized towerlike form symbolizing a city reveal the setting despite the customary gold background. St. Peter and two other apostles are seen behind Christ; the presence of the other nine apostles is indicated simply by fragments of their halos. Indeed, it was quite common in Byzantine mosaics to suggest a crowd by showing several full-length figures with only bits of other figures appearing above or behind them.

The 13th century mosaics in the narthex of St. Mark’s illustrate the building of the Tower of Babel, Noah and the Ark, and other Old Testament scenes that had been more common themes in earlier Byzantine art.

Most of the mosaics of Hagia Sophia were covered by whitewash, plaster, or screens after the Turkish conquest of Constantinople. In 1931 the American archaeologist Thomas Whittemore, with the aid of the Turkish government, began to uncover these mosaics. Some of those in the narthex, jeweled crosses and other designs on a gold ground, date from the 6th century, but most are later in style. The central lunette of the narthex shows Emperor Leo VI (reigned 886-912) kneeling before an enthroned Christ. A 10th century mosaic in the southern vestibule presents the Virgin and Child, with Justinian at the left holding a model of the church and Con-stantine on the right with a model of the city. The south gallery has two important mosaics. The first shows Christ in the attitude of blessing, flanked by Emperor Constantine IX Monomachus and Empress Zoe, who ruled jointly from 1042 until 1050. The second mosaic depicts the Virgin with Emperor John II Comnenus (reigned 1118— 1143) and his mother, Empress Irene. Here also is the important, though fragmentary, 12th century panel of Christ, the Virgin, and St. John the Baptist. In these mosaics the jeweled costumes, stylized folds of drapery, and gold backgrounds are characteristic of the 12th century. The imperial portraits, though far from being realistic, are by no means stereotyped.

Manuscripts.

Some manuscripts of the 10th century, such as the Paris Psalter (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris), suggest a classical Renaissance harking back to figure types of late antique origin. But most of the later Byzantine manuscripts are as similar in style to the mosaics of the time as the differences of technique would permit. The principles and the types of Byzantine manuscripts tend to be fixed from the end of the 9th century, and in the 10th and 11th centuries the art reached its apex, with a progressive decline following this period. The figures, which have a majestic hieratic effect, are anti-realistic in their rigidity, their static poses, and their formal linear outlines of body and drapery. Such stately figures as the portraits of Emperor Basil I and Empress Eudocia with her sons in the Sermons of St. Gregory Nazianzen (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris) are reminiscent in their stiffness and their sumptuous jeweled costumes of imperial portraits in the later mosaics of Hagia Sophia.

A very typical 12th century manuscript is the Melisende Psalter (British Museum), its binding adorned with ivory carvings and studded with turquoises and rubies. Its 24 full-page scenes from the life of Christ were drawn and signed by a Greek craftsman, Basileus. The colors are unusually rich but somewhat discordant. The malproportioned figures with their linear draperies are set against a plain gold background with no more details of setting than is absolutely required by the subject.

Ivories.

One of the best examples of late Byzantine ivory carving is a fine plaque in the Stroganoff Collection, Rome, probably from the 10th century. It depicts the Virgin enthroned with the Christ Child in her lap and half-length figures of angels in the upper corners. For all the flat linearism of the draperies, the carver has endowed the Virgin with a majestic dignity, austere but impressive.

Another masterpiece is the 10th century panel of Christ crowning Emperor Roman IV and Empress Eudoxia (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris). The composition is rigidly symmetrical- Christ stands on a pedestal in the center and places his hands on the crowns of the two rulers, whose poses are nearly mirror images of each other. The drapery of Christ is linear but has substantial breadth, while the drapery of the royal figures are of the jeweled richness familiar from similar subjects in mosaics and manuscripts.

Source : wikipedia.org

Diffusion of Byzantine Art and Architecture.

The influence of Byzantine art and architecture spread even farther than Venice. The plan of St. Front (about 1120), in Périgueux, in western France, was almost identical with St. Mark’s, although the French did not at the the color decoration. Many buildings in this part of France adopted the Byzantine dome on pendentives.

In the Sicilian Romanesque, too, the Byzantine influence was obvious, less in the plan or structure than in the mosaics and colored marbles of the floors and walls. Fine cycles of mosaics may be seen in the Cathedral of Monreale and in the Church of La Martorana and the Cappella Palatina, both in Palermo.

Byzantine influence also extended to the east of the empire, even before the Macedonian dynasty. The dating of Armenian churches is often uncertain. St. Hripsimeh, in Echmiadzin, may have been built as early as 618, but it has been so much restored that it now appears considerably later in style. The Church of Achtamar ( 10th century ) on Lake Van and the Cathedral of Ani ( 1001 ) are typical Armenian Churches of Byzantine style. In the former, tall, V-shaped niches in the outer walls define the limits of the chancel, while flat, pancake like figures are cut into the volcanic stone facing of the walls. A tall drum topped by a pyramidal roof encloses the dome over the center.

When the Venetians, in 1204, diverted the Fourth Crusade to attack Constantinople, a Latin empire was set up there, destined to last only until 1261. The assault from the west, coupled with the Muslim pressure from the east, permanently weakened the Byzantine Empire, and, although it lingered on for two centuries more, Constantinople never regained its former brilliance. Many of the later buildings were small and were erected in the provinces. No single type of plan was dominant; some churches, like St. Basil in Arta, Greece, were simple wooden-roofed basilicas; others perpetuated the characteristic plan of the Macedonian dynasty, as in the Church of the Holy Apostles, Salonika (early 14th century). The drums beneath the domes were so heightened and the domes themselves so small in some cases that they give the effect of towers. An example is the Grachanitsa Monastery in Pristina, (about 1320). This emphasis on the vertical, perhaps the effect of Gothic influence from western Europe, is also apparent in the monastery (after 1407) at Manasija in , which has moldings on the vertical angles of the building.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by the Ottoman Turks, the Byzantine style continued in modified form in Russia. The plans had their basis in earlier precedent, as did the color, but the onion-shaped domes of the Cathedral of the Annunciation ( 1482-1490 ) in Moscow and the adjacent Cathedral of the Archangel Michael (1505-1509) are peculiar to Russia and the Islamic countries. These later buildings became, in a sense, baroque versions of the great Byzantine style of earlier days.

mavi