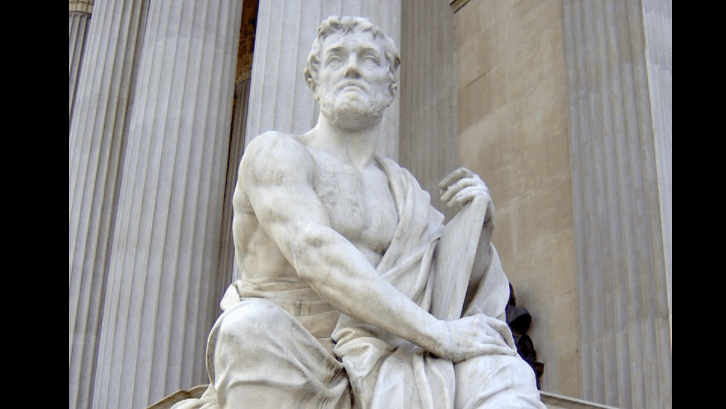

Who is Cornelius Tacitus? Information on one of the greatest Roman historians Cornelius Tacitus biography, life story, works and thoughts.

Cornelius Tacitus;(c.55-c.118 a. d.), one of the greatest Roman historians. Little is known of his life. Roughly accurate guesses can be made about the years of his birth and death, but his parents are unknown. He was a Roman senator who began his official career under Emperor Vespasian (reigned 69-79 a. d.). He reached the consulship under Emperor Nerva in 97 and was proconsul of Asia, probably in 112-113, under Emperor Trajan.

Although Tacitus’ political career was relatively distinguished and his reputation as an orator and a lawyer was very high in his day, it is as a writer and particularly as a historian that he is famous today. Five of his literary works survive, two of them—the Annals and the Histories—only in part.

Source : wikipedia.org

Works:

Tacitus’ earliest work was the Dialogue on Oratory, probably written about the year 80, in which he discusses the decline of oratory in Rome after the days of Cicero. His next work, published in 98, was a biography of his father-in-law, The Life of Gnaeus Julius Agricola. Agri-cola, a Roman senator and general, had been instrumental in the conquest of Britain. In the same year Tacitus published a book on the tribes of Germany, De origine et situ Gerrnanorum, also known as the Germania. It is one of the major sources of information about the German tribes before the barbarian invasions of Rome. All three of these early works are short—fewer than 50 pages each in most editions.

Tacitus’ greatest works are two long histories covering the 1st century a. d., the period of the Julio-Claudian and Flavian emperors from Tiberius through Domitian (14-96). The first to be written, the Histories, covered the last third of the century, the period of the Flavian emperors from 69 to 96. Unfortunately most of the Histories is lost. All that survive are the first four books and a few chapters of the fifth dealing with the years 69 and 70. The Histories must have been very long because the fragments that exist today total more than 200 pages in most editions.

Tacitus’ last and most impressive work was the Annals, covering the history of the Julio-Claudian Rome (14—68) year by year. Only part of the Annals has survived, but the existing books amount to about 400 pages in most editions. The Annals is particularly famous for the opening books on the reign of Emperor Tiberius, in which Tacitus sets forth in powerful, cryptic Latin prose his personal view of Tiberius and his general view of the Roman emperorship.

Tacitus’ Views and Approach:

Tacitus believed that the Roman emperors of the 1st century were evil and capricious men who stifled republican freedoms, practiced arbitrary despotism while hypocritically claiming to champion free institutions, and indulged themselves in moral degeneracy. Under such emperors, according to Tacitus, the Roman Senate was transformed into a body of sycophants who “rushed into slavery.” Tacitus blamed the first Roman emperor, Augustus, for creating the despotism, but directed most of his venom at Augustus’ successor Tiberius, an emperor who “plunged into every wickedness and disgrace.”

Tacitus’ extremely critical view of most of the emperors of the 1st century and his rancorous, virulent prose style have combined to make him the most controversial of all the major Roman historians. In other respects he is very much like his contemporaries. He made no significant methodological contribution to ancient historiography. He was a didactic annalist who saw the gods occasionally at work in the course -of human affairs, although he was usually content with secular rather than divine explanations of causation.

In general, Tacitus was a careful researcher, and even his severest critics ordinarily concede that his facts are accurate. There are mistakes in his works, but no more than in the works of other major historians of antiquity.

He differs from other ancient historians only in his unrelieved pessimism. He was even gloomier than Thucydides. In a famous aside in the Annals he wrote: “So now, after a revolution, when Rome is nothing but the realm of a single despot, there must be good in carefully noting and recording this period. . . . Still, though this is instructive, it gives very little pleasure. … I have to present in succession the merciless biddings of a tyrant, incessant persecutions, faithless friendships, and the ruin of innocence, the same causes issuing in the same results, and I am everywhere confronted by a wearisome monotony in my subject matter. ‘

Evaluations of Tacitus:

Modern scholars have generally been rather critical of Tacitus. Tacitus began his Annah by saying that he was going to write the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty “without either bitterness or partiality,” a claim that seems unjustified by the acrimonious account that follows. Tacitus obviously had a partisan, senatorial bias against the emperors, and some modern historians have argued that Tacitus’ bias was so strong that he deliberately misinterpreted the facts. At several points in his narrative Tacitus relates apparently decent and responsible actions or statements by Emperor Tiberius and then through skillful use of innuendo imputes mean and petty motives. Tacitus also accused Tiberius and other emperors of conducting reigns of terror by arbitrary use of the treason laws against senators. Modern historians have argued that many senators were actually guilty of conspiring against the emperors, as Tacitus’ own facts show.

After World War II, however, Tacitus’ reputation as a historian improved. Modern scholars more readily admit the arbitrary and absolute nature of the Julio-Claudian and Flavian dynasties. Many senators were executed or exiled in the 1st century a. d. Although these senators were frequently guilty of treason, having conspired against the emperors, some historians now argue, in general agreement with Tacitus, that the conspiracies were justified by the repressive nature of the imperial regimes. There are enough documented cases of innocent victims to lend some credence to Tacitus’ sense of outrage.

Tacitus, nevertheless, remains a controversial historian, and he probably always will be. No one who reads him can fail to be impressed by the power of his narration. But some readers, in sympathy with Tacitus, will react strongly against the emperors, and others will cast his historical works aside as embittered, partisan diatribes.