Information on the history of Aztecs. The culture and social organization of Aztecs, how and where they have lived?

Aztecs; one of the Indian tribes that invaded the Valley of Mexico during the 13th century a.d. The name Azteca is derived from Aztlan (Place of the Herons), the original, perhaps mythical, home of the tribe. The chronicles locate this place vaguely somewhere to the northwest of the Valley of Mexico. Chicomoztoc (Seven Caves) is another name for the Aztecs’ place of origin. Before their arrival in the valley they discarded the name Azteca and substituted Mexica, supposedly at the inspiration of their tribal god, Huitzilopochtli. In the 16th century chronicles they are commonly referred to as Mexica, but in modern literature—especially in English—the term Aztecs is generally used.

Some archaeologists, however, prefer to call these people Mexica. When referring to Aztec culture, it is common to enlarge the frame of reference of the term to include closely related peoples of central Mexico at the time of the Spanish conquest. The speech of the Aztecs was Nahuatl, still spoken in central Mexico. It belongs to the Uto-Aztecan linguistic stock, which includes languages once spoken over large areas from Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming south to Nicaragua.

History:

At first, after their arrival in the valley, the Aztecs settled in its northwestern section, in the region of the lakes of Zumpango and Xaltocan. There, for the first time, they made chinampas, artificial islands often called “floating gardens,” built up in shallow water and intensively cultivated. It is probable that this horticultural technique, though new to the immigrant Mexica, was long known in the valley.

Later, the Aztecs moved to the Hill of Chapultepec, which they fortified with stone walls and where tradition records the establishment of a kingship, the first king being Huitzilihuitl, the elder. Then Culhuacan, at that time the leading city-state in the valley, and its allies attacked the Aztecs, inflicting a crushing defeat on them. Their king was taken as a prisoner to Culhuacan and sacrificed, and the tribe was confined to Tizapan, in the southern section of the valley.

Finally, they settled on an island in the western part of Lake Texcoco, where two sections of the tribe founded the twin towns of Mexico-Tenochtitlan and Mexico-Tlatelolco, from which are derived the tribal names Tenochca and Tlatelolca. The date traditionally accepted by most historians for the founding of Tenochtitlan is 1325, although various sources give dates ranging from 1194 (certainly much too early) to 1366. The dates for Tlatelolco range from 1325 to 1338. Research in the 1940’s on the correlation between the several Indian calendars and our own led to discoveries that corrected these dates and indicated that 1345, 1349, or sometime between 1368 and 1371 are the most probable dates for the founding of both Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco. Culhuacan gave Tenochtitlan its first king, Acamapichtli. The first king of Tlatelolco, Cuacuauhpitzahuac, was a son of the king of Azcapotzalco. The traditional date for the beginning of these reigns is 1375.

Until 1428 the Tenochca and Tlatelolca were vassals of Azcapotzalco, which from 1347 to 1428 held the political hegemony of the valley and was extending its dominion through wars of conquest in which the Mexica, as vassals, helped. In -1428, Chimalpopoca, king of Tenochtitlan, and Tlacateotl, king of Tlatelolco, were executed by order of the king of Azcapotzalco. Their killing was part of a series of executions of vassal lords suspected of disloyalty. However, a rebellion broke out in the same year. Its leaders were Itzcoatl, successor to Chimalpopoca, and Nezahualcoyotl, legitimate heir to the kingdom of Texcoco, whose father was one of the murdered vassal kings. The rebels had the help of the Tlaxcaltec. The war began with the storming of Azcapotzalco (1428) and ended with the enthroning of Nezahualcoyotl at Texcoco (1431).

To fill the political vacuum left by the destruction of the power of Azcapotzalco, a triple alliance of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan was established. The people of Tlacopan and Azcapotzalco belonged to the same tribe, the Tepanec, but Tlacopan was included in the confederacy, probably for reasons of maintaining the balance of power between the victors. At first, the alliance was an instrument for the political consolidation of the valley, later for imperial expansion. The Tenochca became the dominant power of the confederacy and were able to build an empire in central and southern Mexico that, by 1519, covered about 75,000 square miles (194,000 square kilometers) and had a population of 5 to 6 million people.

Relations between Tenochtitlán and Tlatelolco, which appear to have been strained from the start, came to a crisis in 1473. Axayacatl, king of Tenochtitlán, stormed the rival city and the Tlatelolcan king, Moquiuix, was killed or committed suicide. From this time on, Tlatelolco was administered through cuauhtlahtoque, governors under the control of Tenochtitlán.

In 1519, Hernán Cortés arrived. In 1521 the twin cities were stormed by the Spaniards and their Indian allies, the Aztecs making their last resistance in Tlatelolco. Subsequently, the conquistadores founded Mexico City on the debris of the twin cities.

Culture and Social Organization:

When the primitive Aztecs first appeared in history, they were already undergoing a process of acculturation— that is, adaptation to the ways of life of the civilized peoples of central Mexico. We know much of the subsequent development of that culture, after the establishment of their twin city-states, Tenochtitlán and Tlatelolco. By the time of the Spanish conquest, these had become large urban communities. The first as a political center and the second as a commercial center concentrated, through tribute and trade respectively, the surpluses produced in large areas of central and southern Mexico.

The size of the cities, their temples, palaces, and markets, and the causeways linking the island, on which the cities were situated, to the mainland excited the admiration of the Spaniards. Their joint urban population was probably between 50,000 and 75,000. Some estimates make it as high as 300,-000, certainly too high considering the extent of the urbanized area. A large part of the population were nobility and its retinue, the priesthood, merchants, and specialist craftsmen. It seems that the major part of the food supply for the urban population came from exterior sources, supplemented by the products of the garden plots and of the chinampas surrounding the island and by fishing.

Technologically, at the time of the conquest, the Aztecs, as all the other peoples in central Mexico, were in transition from the Neolithic to a metal stage, using mainly chipped and polished stone tools but also some metal (copper or bronze, and gold) for craftsmen’s tools and for ornaments. Society was stratified, with an upper class composed of nobility and merchants; the lower classes were plebeians, mayeques, and slaves. The nobility had privately owned estates. The plebeians had communal lands owned by the calpulli, or clan, and allotted to individual members of the clan. The mayeques worked the estates of the nobility and had a position similar to serfs, being transferred with the land. Kingship was, in theory, elective among the members of the royal family. In practice, it seems to have been hereditary, with the succession from brother to brother in a generation and then to the sons of the eldest brother in like manner.

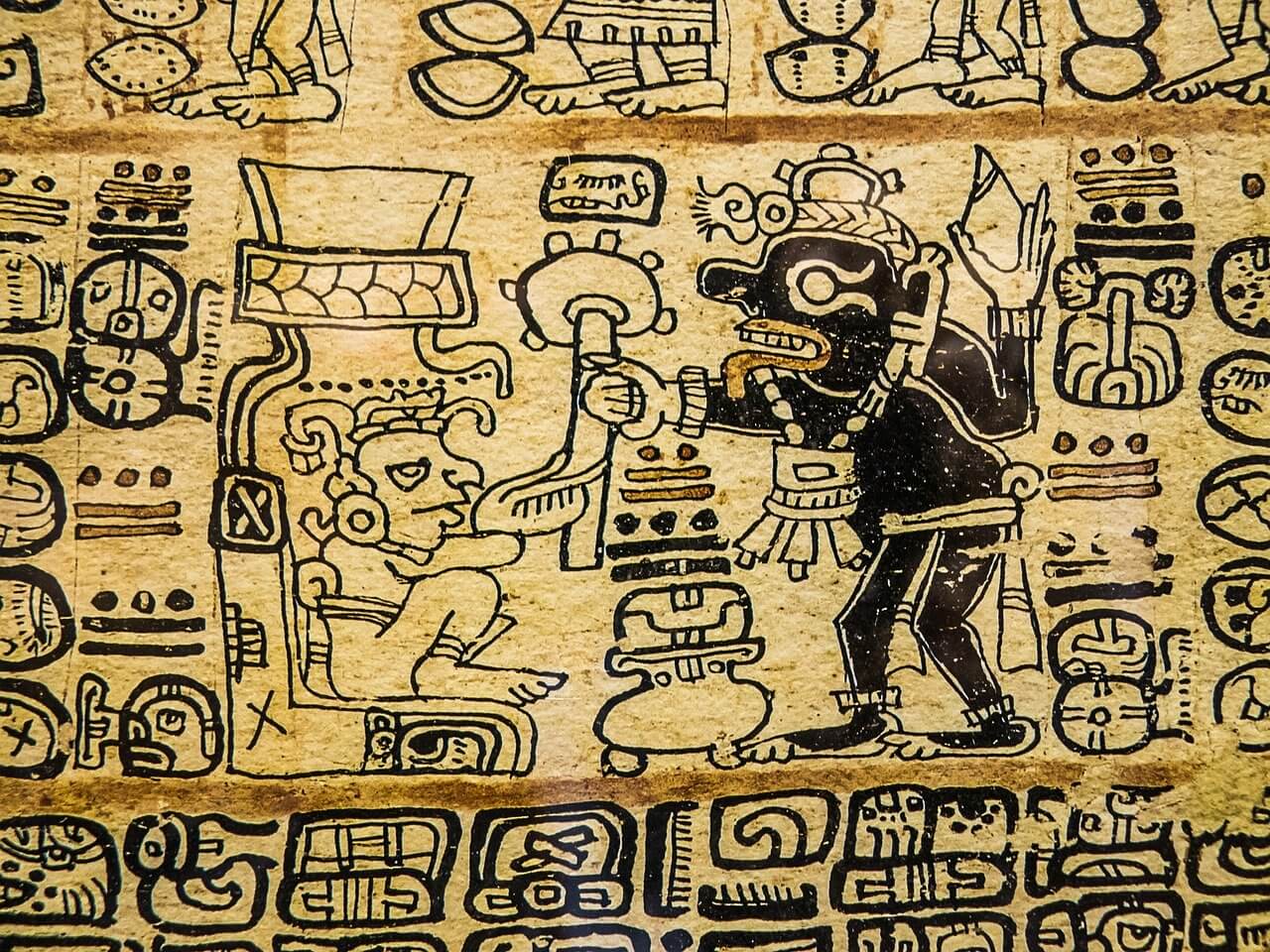

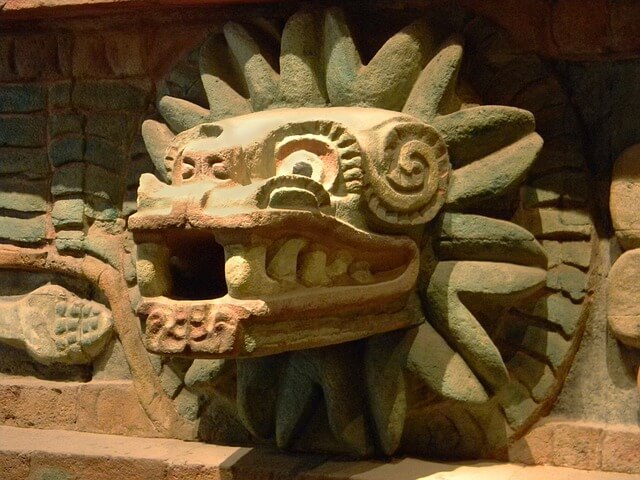

The major pyramids of Tenochtitlán and Tlatelolco had two sanctuaries each, one for Huitzilopochtli and the other for Tlaloc, the rain god. Human sacrifices were made to the gods, especially Huitzilopochtli, who besides being the tribal god was the war god and identified with the sun. In major ceremonies, thousands of war prisoners are said to have been sacrificed. The flesh of the sacrificed was eaten for religious motives, symbolizing form of communion with the deities.