Who was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow? What did Henry Wadsworth Longfellow write? Information on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow biography and works.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow; (1807-1882), American poet and scholar. While not so major a poet in absolute terms as either Whitman or Emily Dickinson, he had one ability beyond that of any other American poet of his own day, or ours—the power of mythmaking, the creation of figures that would become forever a part of the American Pantheon.

Before the publication of Paul Revere s Ride (1860), no one had ever heard of its hero, but the poem carried him to immortality. Priscilla and John Alden are, as we remember them from The Courtship of Miles Standish, Longfellow’s inventions. The Song of Hiaivatha is much more than a brave adaptation of the trochaic tetrameters of the Finnish epic Kalevala. Even The Village Blacksmith is a visual figure not to be forgotten, trite as may be the lines:

Thanks, thanks to thee, my worthy friend. For the lesson thou has taught!

The census of Longfellow’s memorable characters, his blacksmith included, is large enough to warrant that an artist’s skill created them.

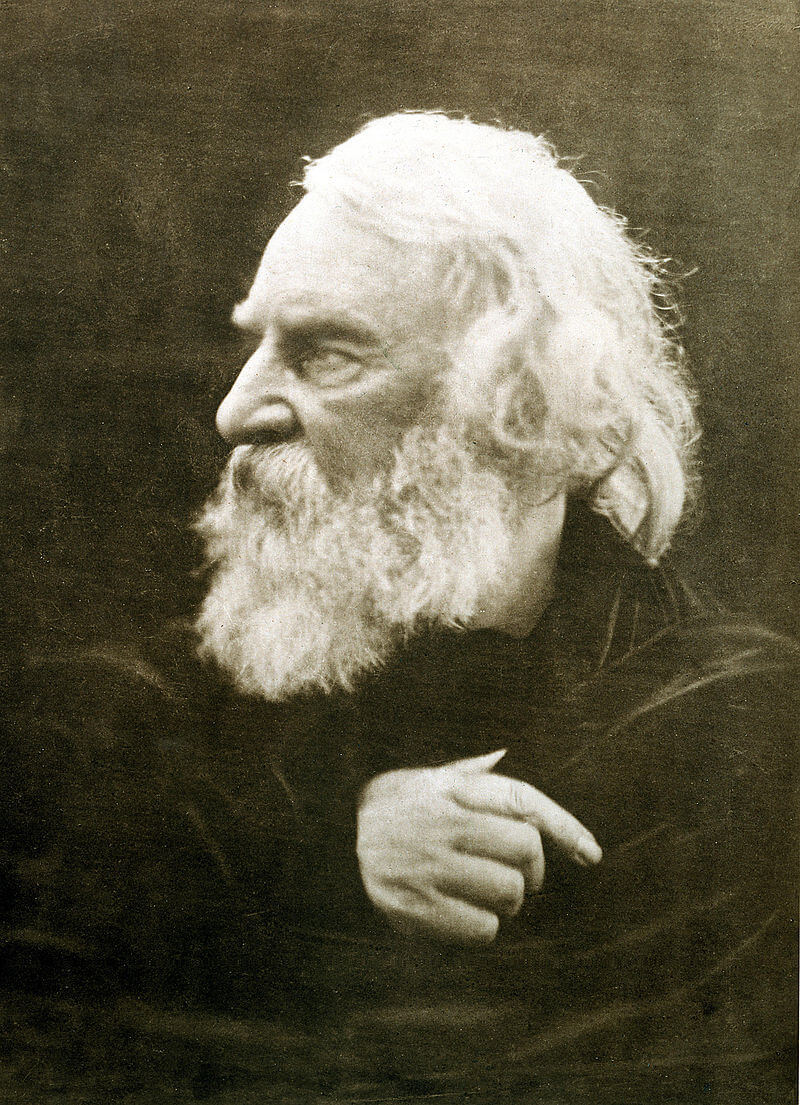

Source : pixabay.com

Early Years.

Longfellow was born in Portland, Me., on Feb. 27, 1807, the second son of Stephen Longfellow, a lawyer, congressman, and graduate of Harvard. His mother was Zilpah, the daughter of Gen. Peleg Wadsworth, a local Revolutionary War hero. Henry was brought up in Portland in the handsome Wadsworth-Longfellow mansion (now a museum) in an atmosphere of cultivated good breeding, where books provided a landscape that was even broader than the picturesque countryside of Maine.

Longfellow took every advantage of his reading, published several poems in a Portland paper, and was ready to enter Bowdoin College, in nearby Brunswick, at the age of 14. However, a year later, he entered as a sophomore and became a classmate of Nathaniel Hawthorne. But the paths of the two fledgling writers seldom crossed, and it was not until after 1837—when Longfellow helped Hawthorne by warmly reviewing his Twice-Told Tales—that the two became close friends.

As a student, Longfellow led a quieter life than Hawthorne, \yas increasingly drawn toward faculty friendships, and by his senior year had begun a precocious literary activity that resulted in the publication of numerous essays and poems in the American Monthly Magazine and the United States Literary Gazette. His idol was Washington Irving, and his model was Irving’s graceful sketches of a romanticized Europe.

Finding a Profession.

Upon graduating from Bowdoin in 1825, Longfellow wished to associate himself editorially with some magazine. “The fact is,” he wrote his father, “I most eagerly aspire after future eminence in literature. . . . Surely there never was a better opportunity offered for the exertion of literary talent in our own country than is now offered. To be sure, most of our literary men, thus far, have not been professedly so, until they have studied and entered the practise of Theology, Law, or Medicine. But this is evidently lost time.” His father, not untypically of the age, was unconvinced. “A literary life,” he replied, “to one who has the means of support, must be very pleasant. But there is not wealth and munificence enough in this country to afford sufficient encouragement and patronage to merely literary men.” The elder Longfellow wanted his son to study law, but when an offer of a professorship of modern languages came from Bowdoin, provided Henry would prepare himself for it by a period of study abroad, his father agreed.

Accepting the profession of teaching as a reasonable economic compromise, Longfellow spent the years 1826 to 1829 traveling in France, Spain, Italy, and Germany. This was the period that laid the foundation for his eventual mastery not only of the languages and literatures of those countries, but also of Swedish, Finnish, Dutch, and Portuguese as well as the classical languages and Old English and Provençal. More immediately significant to him, however, was the actual contact with a romantic past that contrasted appealingly for him, as for so many of his contemporaries, with the apparent barrenness of his own country—a difference that Longfellow later attempted to bridge.

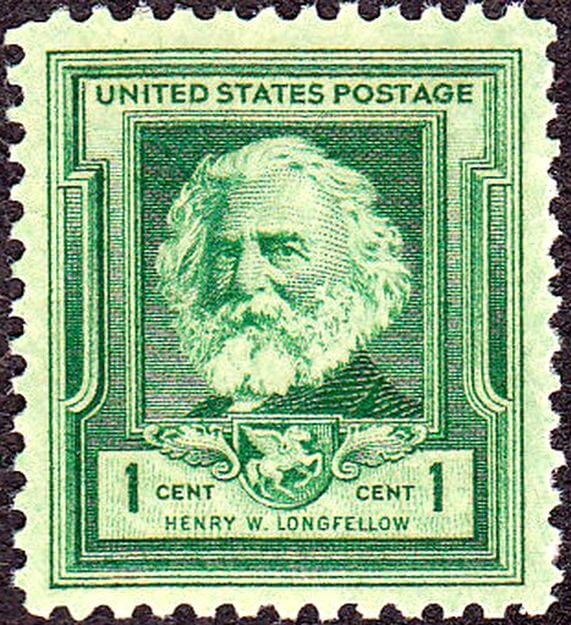

Source : pixabay.com

Bowdoin and Harvard.

Longfellow began to teach at Bowdoin in 1829 and held his professorship there until 1835. In the meantime, in 1831, he married the delicately beautiful and frail Mary Storer Potter of Portland.

His teaching schedule at Bowdoin was heavy and uninspiring, and Longfellow’s eye was therefore on a broader horizon. “I will be eminent in something,” he said. Publication was a means. He edited several textbooks in French and Spanish, continued to write essays for periodicals, and published Outre-Mer: a Pilgrimage Beyond the Sea (1835), parts of which had appeared separately in 1833 and 1834. In its essays, modeled on Irving’s Sketch Book (1820), he gave succulent impressions of Europe.

Tactful efforts to secure a better academic position, coupled with his very real success as a teacher at Bowdoin, finally won Longfellow appointment as Smith professor of modern languages at Harvard in 1835, and again he left for a period of further study abroad. This time, so that he could have more freedom for study, he and his wife took with them her friend Clara Crowninshield, whose diary of the trip was published in 1956. Longfellow concentrated on German and the Scandinavian languages. His trip was saddened after a few months, however, by the death of his wife, who had been stricken by puerperal fever in Rotterdam. Despite his loss, he stayed on in Europe, and his winter in Heidelberg brought him into contact with the sentimentality of romantic German literature. Its mood appealed both to his nature and to his bereavement, and it had a strong influence on him.

In the fall of 1836, Longfellow began teaching at Harvard, and in 1837 he took lodgings in the stately and historic Craigie House (now a museum) in Cambridge, known both for its architectural beauty and because George Washington had made it his headquarters for a time while commander in chief of the Continental Army. Longfellow’s gay European waistcoats caused him to stand out, and his easy manner made him a favorite both in society and with his students. His own writings and his sound knowledge of foreign literatures brought him the friendship of those who were then making Cambridge and Boston so remarkable. Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Sumner, Louis Agassiz, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and James Russell Lowell were among the many who gathered at Craigie House, with good wine for refreshment and a growing Jibrary as a background and reference point.

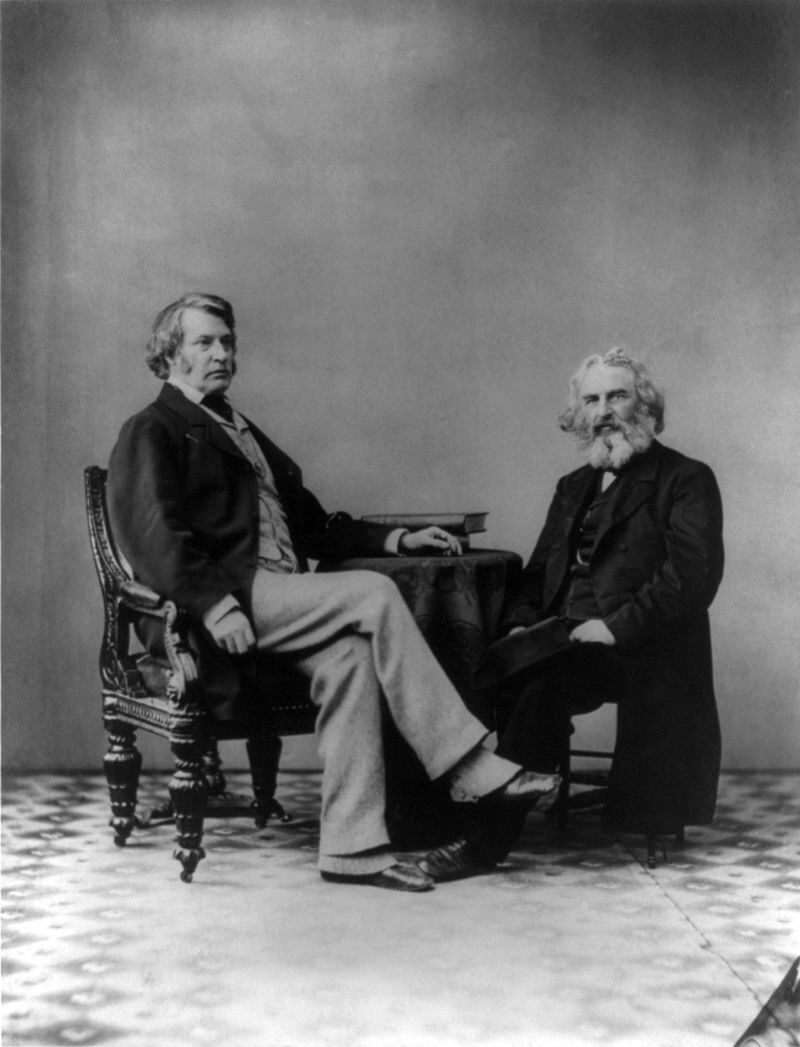

Source : pixabay.com

Longfellow’s books were indeed more than a background. As a professor at Harvard, he lectured brilliantly on the various literatures of which he became increasingly a master, drawing upon his books not only for basic data but also for the many poems that he translated as illustrations. The practice of translation perfected his technical versatility beyond that of any American contemporary. By this means also he gave Americans a knowledge of foreign verse forms to add to their knowledge of English poetry. His editing of The Poets and Poetry of Europe (1845), an anthology that included many of his own translations, was an important milestone in American literary cosmopolitanism.

Second Marriage.

Another milestone, personally more significant to Longfellow, was the publication in 1839 of his first volume of original poems, Voices of the Night (which included the popular and often parodied Excelsior), and his prose romance Hyperion, which wove together the strands of his life up to that point. Based on his second journey abroad, Hyperion was a highly sentimental mixture of foreign landscapes and professorial lectures on German romantic poets and a thinly veiled account of his continued and unsuccessful courtship of dark-eyed Fanny Appleton, the daughter of a wealthy merchant of Boston, whom he had first met in Switzerland after his wife’s death.

At the end of Longfellow’s romance, the hero sadly leaves his love forever, but no author ever actually wished less to be believed. The book sold well enough to give him confidence in a literary income, but its detailed emotional frankness made it disastrous as a valentine to be delivered on Beacon Hill.

In 1843, Miss Appleton at last relented and bestowed both her hand and a helpful income upon him. His new father-in-law completed his happiness by presenting Craigie House as a wedding gift. Longfellow was able to maintain it so adequately by his pen that by 1854 the necessity for any professional compromise was over. By this time he had already published many of his most popular works, including The Village Blacksmith (1840); Ballads and Other Poems (1841), containing the ballad The Wreck of the Hesperus; Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie (1847); and The Golden Legend (1851). He resigned from Harvard to become simply and solely an author and published several works in the next few years, notably The Song of Hiawatha (1855) and The Courtship of Miles Standish, and Other Poems (1858).

Longfellow’s six children were born in Craigie House, and he shared with his readers his love for them in the charming domestic conceit of The Children’s Hour (1860). He had an ideal life at Craigie House until 1861, when his wife died from burns after her dress caught fire. He commemorated her in the touching sonnet The Cross of Snow (written 1879; published 1886).

Later Years.

At the time of his wife’s death, Longfellow was at work on Tales of a Wayside Inn (1863), his popular collection of stories in verse, and he managed to finish it after the tragedy. Thereafter he channeled his grief into the prolonged translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1865-1867) and the composition of a series of six sonnets, one to precede and one to follow each division of Dante’s epic. The translation helped to introduce Dante to American readers, not only in the academies but to the public at large, which read it because it had been made by Longfellow. He was their poet.

The closing years of Longfellow’s life were satisfying ones, despite the loss of his second wife. His steady output of verse continued, and translations of his works appeared in so many languages that he became at least a part of those literatures he had once taught. Distinguished visitors to the United States never failed to sit at his table in Craigie House, and lesser travelers looked at it from outside or wrote him countless letters to which he cheerfully replied. During a tour of Europe that he made in 1868-1869, Oxford and Cambridge universities conferred honorary doctorates upon him. Longfellow died in Cambridge on March 24, 1882. Two years later a bust of him was unveiled in Westminster Abbey. He was the first American to be so honored.

Source : pixabay.com

Evaluation.

Few writers of quality have understood the people better than Longfellow did or have given them so much of what they could take to their hearts. Poem after poem gained wide popularity, were read and reread, not only in the United States but on the Continent and in England, where he was the poet most widely read by all classes. Longfellow divided his work into two categories, that for the “court” and that for the “people,” and the latter rewarded him most.

Of Longfellow’s eventual refutation of his father’s early fears of authorship as a means of livelihood, the American scholar and critic William Charvat—in a 1944 article on Longfellow’s income from writing—said, “It is no small matter that he was the first American writer to make a living from poetry—that by shrewd, aggressive, and intelligent management of the business of writing, he raised the commercial value of verse and helped other American poets to get out of the garret.”

Much, however, that was once popular in Longfellow’s poetry has become tawdry. A poem like A Psalm of Life (1838), which swept the country with

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

is now remembered chiefly in parody. But it is too easy to dismiss Longfellow as the “poet laureate of the commonplace.” One has only to iplace against what is humdrum the exquisite modulation of such a line as this from Evangeline,

Water-lilies in myriads rocked on the slight undulations,

to recognize the ear of a true poet. Even if much of what Longfellow wrote were discarded, there would still be enough left to support a significant reputation.

mavi