Who is George Bernard Shaw? What did George Bernard Shaw do? Information on George Bernard Shaw biography, life story, works and plays.

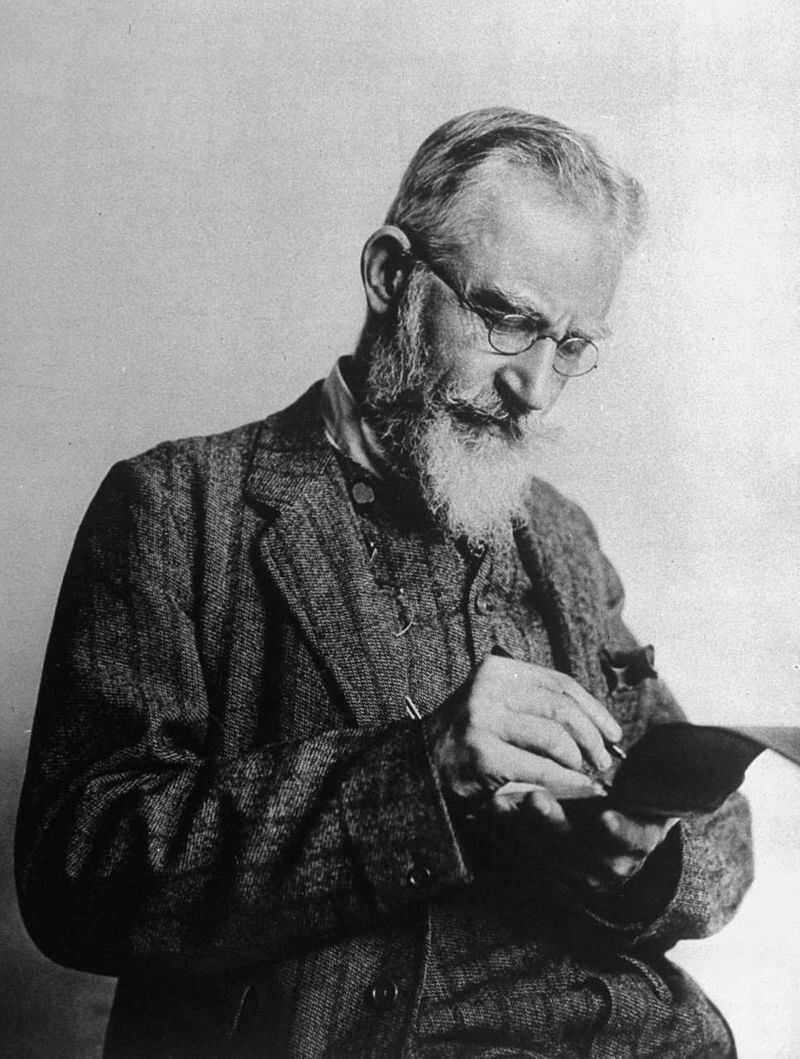

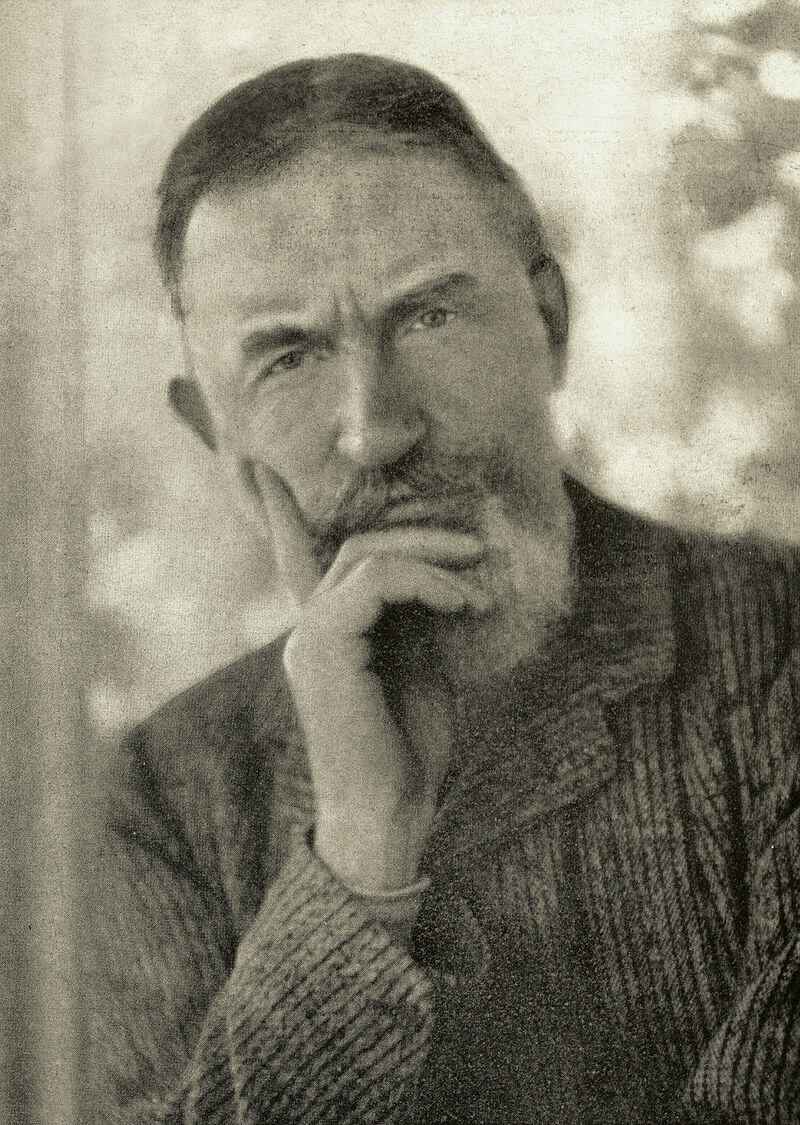

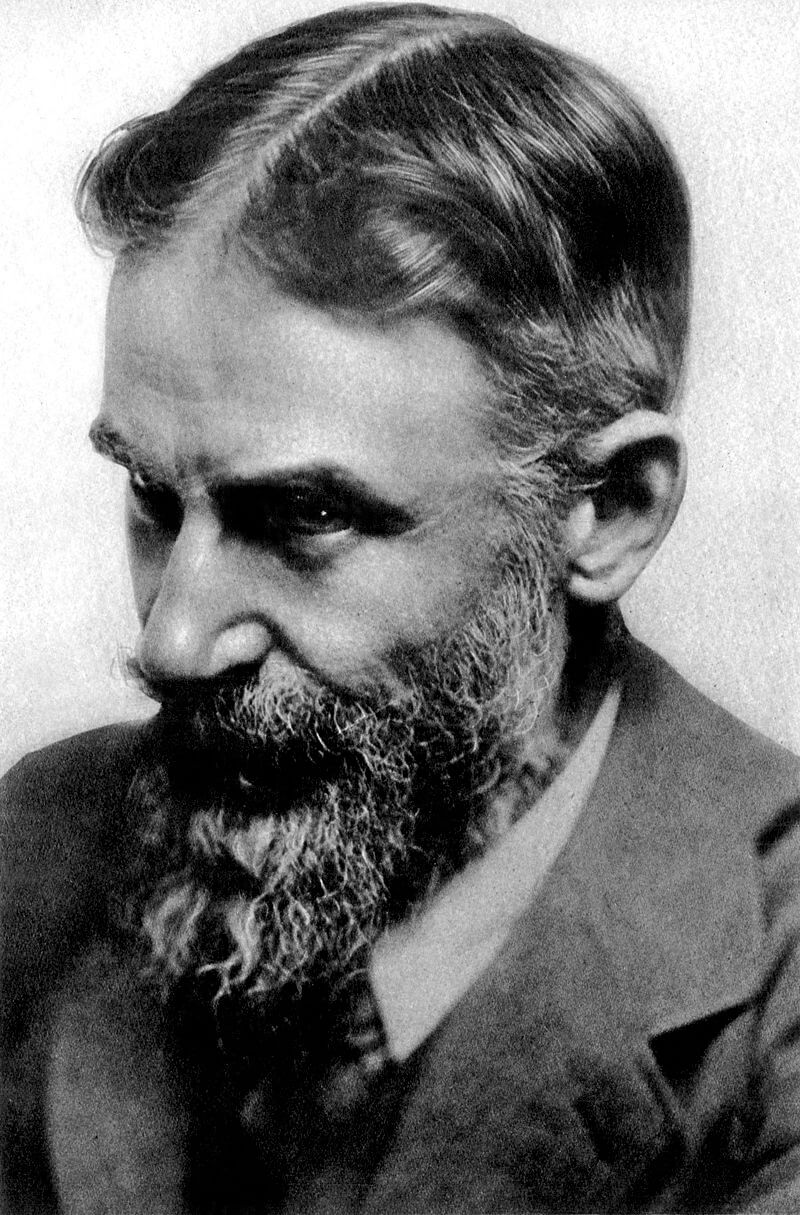

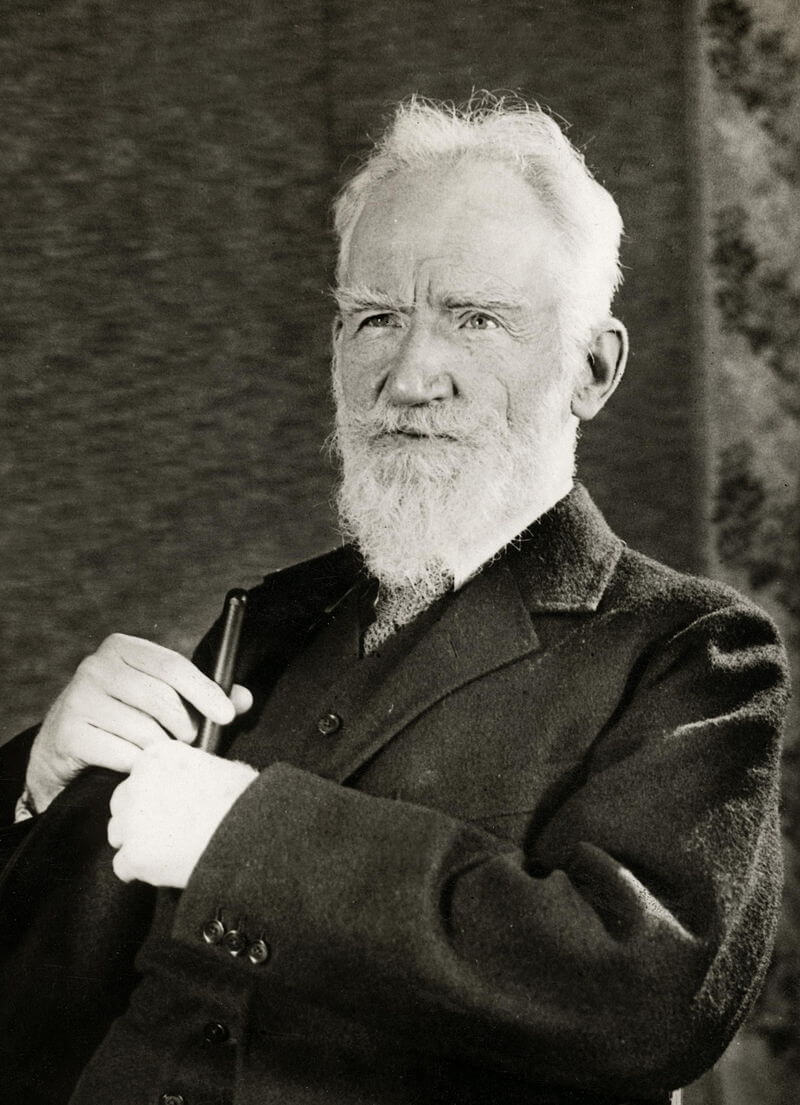

George Bernard Shaw; (1856-1950), British playwright, critic, man of letters, socialist pamphleteer, and lecturer, who was one of the most influential figures in modern literature. He was almost 40 before he began to taste success, but although his career began with painful and fumbling slowness it culminated with his receiving the Nobel Prize for literature in 1926. Shaw continued to write almost until his death at 94, producing about 50 plays, many of which are among the classics of Western theater.

Shaw’s attitude to the drama and the stage was sharply unconventional. He believed in the theater as a place not for mere entertainment but for serious thought about man and society— “a temple of the ascent of man,” he called it. The fact that his greatest successes were comedies in no way lessens the seriousness. For him, laughter was a means to clarity of thought, strength of purpose, and healthier feeling.

Source : wikipedia.org

Shaw’s medium was prose—pungently athletic, musical, resilient, witty. In analytical and argumentative force, it is unexcelled. His work is sometimes poetic, but his occasional attempts at verse make it clear that his decision to hold with prose was a wise one.

Early Life.

Shaw was born in Dublin, Ireland, on July 26, 1856, of Anglo-Irish stock. His parents were unhappily married, and his mother left his father during Shaw’s adolescence. Shaw later claimed that he had learned nothing creditable in the various schools he attended, but a great deal from visits to the National Gallery of Ireland and the theater, from the reading that he was allowed to pursue at will, and from the music in which the household was continuously involved. The two individuals who most influenced him as a boy were his mother, who was a singer and pianist, and George Vandeleur Lee, a conductor and music teacher, who was part of the Shaw ménage for many years. In 1876, after working for five years as a clerk in a real estate office, Shaw resigned and went to London, where his mother, sisters, and Lee had already gone.

For the next decade, Shaw’s life was irregular, restless, and obscure as the family circumstances steadily declined. He read omnivorously at the British Museum, attended countless meetings of literary and debating societies, and assisted in the musical activities of Lee. He also adopted his lifelong habits of vegetarianism and teetotalism. In 1879 he wrote Immaturity, a long and clumsy novel, which nevertheless has flashes of self-portraiture and glimpses of the future master of prose debate. Four more novels followed: The Irrational Knot, Love Among the Artists, Cashel Byron’s Profession, and An Unsocial Socialist. These were published in serial form in socialist magazines. The novels expressed their author’s unconventional and mainly rationalistic views on religion, marriage, the arts, and society.

In 1882, Shaw’s as yet unformed attitudes and ideas on socialism were suddenly given focus when he attended a lecture by the American economist Henry George, which led him to recognize that economics must be at the center of socialist thought. He set himself to master David Ricardo, Stanley Jevons, John Stuart Mill, and Karl Marx. In 1884 he joined the recently founded Fabian Society, of which he and Sidney and Beatrice Webb constituted the dynamic intellectual center for many years. He wrote tracts for the society, edited a volume of essays, and lectured and debated interminably. Although by the late 1890’s his energies were increasingly directed to the theater, he never lost his belief in socialism as the only way to fundamental social betterment.

Source : wikipedia.org

Shaw’s religious thought developed in the same period. He had abandoned Christianity in his teens and become a rationalist and agnostic. In the 1880’s he mingled in circles where evolutionary theory was much discussed, and in 1887 he read Samuel Butler’s Luck or Cunning?, in which the mechanistic implications of Darwinism were attacked. Butler argued that evolution was the expression of a purposeful force of will in the universe, not the effect of mere mechanical causation and chance. Shaw’s reading of Butler led to the formulation of his theory of a “Life Force” that, through biological change, continually seeks higher living forms through which to achieve its goal of perfect contemplation. This “religion,” which owed much to William Blake, as well as to Butler, provided the philosophical basis of virtually all Shaw’s writings after the mid-1890’s, especially his plays.

Musical and Dramatic Criticism.

In the mid-1880’s, thanks to the efforts of the drama critic William Archer, Shaw began to earn a living through journalism—writing book reviews and accounts of concerts, art exhibitions, and plays. From 1888 to 1894 he reviewed the musical life of London, first under the pseudonym “Como di Bassetto” and then under the initials G. B. S. Shaw’s knowledge of music was vast. More than 30 years after his criticisms appeared, Ernest Newman called them “the most brilliant things that musical journalism … is ever likely to produce.” Shaw felt that music, especially opera, was the noblest of the arts. His tastes were catholic, but his highest preference was for Mozart. He was an early Wagner enthusiast and wrote a long critical essay, The Perfect Wagnerite (1898). Shaw was also an early admirer of Sir Edward Elgar, and they shared a long friendship.

In 1895, Shaw became a dramatic critic for the Saturday Review, and for three and a half years he discussed the London theatrical scene. He mercilessly attacked the conventional plays of the period and challenged writers and producers to transform the theater into what he believed it ought to be: a place for the dramatic presentation and discussion of human problems. He scoffed at the universal unquestioning reverence for Shakespeare, which he called “Bardolatry,” and he attacked Henry Irving, the actor who especially embodied it. In Shaw’s view, drama had to find new and worthier courses, such as those that Ibsen was exploring. Ibsen had become a hero for Shaw, who wrote one of his major essays, The Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891) about him.

Early Plays and Marriage.

Shaw’s first three plays, Widowers’ Houses (1892; dates of completion throughout), The Philanderer (1893), and Mrs. Warren’s Profession (1893), deal with social questions such as slum landlordism and prostitution. His gift for satirical comedy appears fully in Arms and the Man (1894), a spoof on the romanticized view of war, and his first successful play. Its comic stripping away of illusions and pretensions pointed in the direction that his plays of the next 20 years would take. Its initial success was limited, however, as was that of Candida (1894), though this later became one of his most popular comedies.

In 1898, Shaw married Charlotte Payne-Townshend, an Irish heiress and fellow Fabian. They lived in London for a time and then moved to Ayot St. Lawrence, Hertfordshire, their home for the rest of their lives. Their marriage, which was childless, lasted 45 years. Shaw was by now a public figure, but the quiet of Hertfordshire enabled him to write with prodigious industry.

Source : wikipedia.org

Plays, 1895 to World War I.

After Candida, virtually all of Shaw’s plays dealt with social problems and problems of individual growth, seen in the light of his belief in the Life Force. Candida itself, with its mockery of conventional Victorian domesticity and its ending in which the young poet Marchbanks is liberated from illusion to carry out life’s nobler purposes, set a pattern for several plays of “conversion.” These plays, in which one or more of the protagonists is led to self-discovery and the possibility of self-ful-fillment, include The Devil’s Disciple (1897), Captain Brassbound’s Conversion (1899), The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet (1909), and An-drocles and The Lion (1912).

In other plays, he explored the nature of the “great man” through whom the Life Force reaches forward in evolution: Napoleon, in The Man of Destiny (1895); Julius Caesar, in Caesar and Cleopatra (1898); and the rich munitions-maker Sir Andrew Under-shaft, in Major Barbara (1905). In Man and Superman (1903), subtitled A Comedy and a Philosophy, Shaw affirmed his belief in the Life Force more fully and overtly than in any other play of this period. In all his plays, however, the theme of the Life Force provides only one of the major threads. His attacks on social ills were unceasing—on poverty, in Major Barbara; on questionable medical practices, in The Doctor’s Dilemma (1906); on England’s treatment of Ireland, in John Bull’s Other Island (1904); and on the British class structure, in Pygmalion (1912).

He also exposed some of the shams inherent in many social conventions and institutions, such as marriage, in Getting Married (1908) and in Misalliance (1910), and dealt with family relationships, the status of women, and other subjects in other plays.

The mood and action of these plays are those of high comedy, breaking occasionally into farce. The method is rather of discussion than of action, since Shaw’s interest was much more in the high-spirited clash of ideas than in the depiction of events or the conflicts of passion. In their published form, many of the plays are accompanied by “prefaces,” in which Shaw discussed the theater, himself, and a wide range of social and philosophical questions.

World War I and After.

In the early weeks of World War I, Shaw published a pamphlet, Common Sense about the War, in which he castigated the diplomacy and militarism of all those who had made the war possible. Because he condemned the British and French as well as the Germans, he experienced a period of intense unpopularity, which waned only as he turned to pamphleteering for the cause of the Allies. The sense of near despair that he experienced in this period found expression in Heartbreak House (1916), which was much influenced by Chekhov. The play, with its country house setting that resembles a ship, its eccentric characters, and its brooding atmosphere of aimlessness and futility broken by episodes of farce, is unlike any other by Shaw.

In the later years of the war, Shaw wrote several short pieces in his former vein of burlesque comedy. Then came Back to Methuselah (1920), actually five plays in one, in which he propounds fully and imaginatively the theory of the Life Force, beginning back with the Garden of Eden and ending with a time ahead “as far as thought can reach,” when the span of life has been extended to centuries and life itself has virtually become thought. It was followed by Saint Joan (1923), probably his most popular play. It is a study based on the life of Joan of Arc, exploring the forces in conflict around her by the Shavian devices of dramatic debate.

Source : wikipedia.org

Shaw’s continuing concern with economics and socialism was reflected in The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (1928) and in the later Everybody’s Political What’s What? (1944). It was also reflected in a lecture that he gave at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York in 1933, published later that year as The Political Madhouse in America and Nearer Home. In despair over the ineptitudes of parliamentary democracy, he praised communist Russia. For a time he became an admirer of such figures as Lenin, Stalin, and Mussolini. Some of the plays of his later years express these feelings, though the mood of high comedy continues to enliven them. They include The Apple Cart (1929), The Millionairess (1936), and Buoyant Billions (1947).

In his 95th year, Shaw fractured his thigh after falling from a tree that he was pruning in his garden. He died in Ayot St. Lawrence on Nov. 2, 1950. It is reported that on that night, theaters around the world were darkened in his honor.