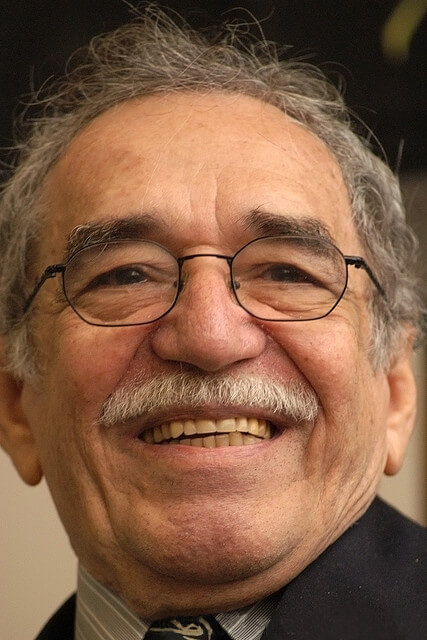

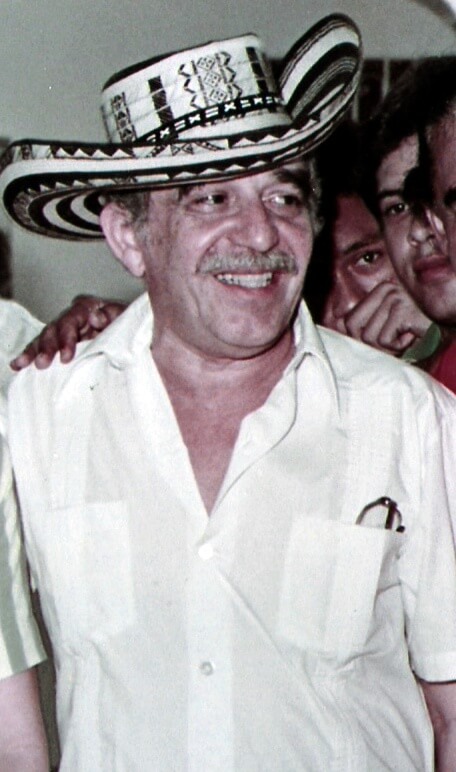

Gabriel García Márquez (March 6, 1927 – April 17, 2014) was a famous Colombian novelist, short story writer, screenwriter and journalist, affectionately known as Gabo or Gabito throughout Latin America.

Considered one of the most important authors of the 20th century and one of the best in the Spanish language, he was awarded the 1972 Neustadt International Literature Prize and the 1982 Nobel Literature Prize. He pursued a self-directed education that resulted in his departure from law school for a career in journalism. From the beginning, he showed no inhibitions in his criticism of Colombian and foreign politics. In 1958, he married Mercedes Barcha; They had two children, Rodrigo and Gonzalo.

García Márquez began as a journalist, and wrote many non-fiction acclaim works and short stories, but is best known for his novels, such as One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975) and Love in The Time of Cholera ( 1985). His works have achieved great critical acclaim and great commercial success, especially to popularize a literary style known as magical realism, which uses magical elements and events in normal and realistic situations. Some of his works are in the fictional town of Macondo (mainly inspired by his birthplace, Aracataca), and most of them explore the theme of loneliness.

After the death of García Márquez in April 2014, Juan Manuel Santos, the president of Colombia, called him “the greatest Colombian that has ever existed.”

Early life

Gabriel García Márquez was born on March 6, 1927 in Aracataca, Colombia, son of Gabriel Eligio García and Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán. Shortly after García Márquez was born, his father became a pharmacist and moved with his wife to Barranquilla, leaving the young Gabriel in Aracataca. He was raised by his maternal grandparents, Doña Tranquilina Iguarán and Colonel Nicolás Ricardo Márquez Mejía. In December 1936, his father took him and his brother to Sincé, while in March 1937, his grandfather died; the family then moved first (back) to Barranquilla and then to Sucre, where his father started a pharmacy.

Source : wikipedia.org

When their parents fell in love, their relationship met the resistance of Luisa Santiaga Márquez’s father, the Colonel. Gabriel Eligio Garcia was not the man the Colonel had imagined winning the heart of his daughter: he (Gabriel Eligio) was a conservative and had the reputation of being a womanizer. Gabriel Eligio courted Luisa with violin serenades, love poems, innumerable letters and even telephone messages after her father dismissed her with the intention of separating the young couple. His parents tried everything to get rid of the man, but he kept coming back, and it was obvious that his daughter was engaged to him. His family finally capitulated and gave him permission to marry him (the tragicomic story of their courtship would then be adapted and recast as Love in the Time of Cholera).

As García Márquez’s parents were more or less foreign to him during the first years of his life, his grandparents strongly influenced his early development. His grandfather, whom he called “Papalelo”, was a veteran liberal of the War of a Thousand Days. The Colonel was considered a hero by the Colombian Liberals and was highly respected. He was known for his refusal to remain silent about the banana massacres that took place one year after the birth of García Márquez. The Colonel, whom García Márquez described as his “umbilical cord with history and reality,” was also an excellent narrator. He taught García Márquez the dictionary lessons, took him to the circus every year, and was the first to introduce his grandson to him, a “miracle” found in the United Fruit Company store. Occasionally he also told his young grandson “You can not imagine how much a dead person weighs”, reminding him that there was no greater burden than having killed a man, a lesson that García Márquez would later integrate into his novels.

García Márquez’s grandmother, Doña Tranquilina Iguarán Cotes, played an influential role in her education. He was inspired by the way he “treated the extraordinary as something perfectly natural.” The house was full of stories of ghosts and premonitions, omens and portents, all of which was carefully ignored by her husband. According to García Márquez, she was “the source of the magical, superstitious and supernatural vision of reality”. He enjoyed the unique way of telling stories of his grandmother. No matter how fantastic or improbable her statements are, she always delivered them as if they were the irrefutable truth. It was an expressionless style that, some thirty years later, strongly influenced the most popular novel of his grandson, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Education and adulthood

After arriving in Sucre, it was decided that García Márquez would begin his formal education and was sent to an internship in Barranquilla, a port at the mouth of the Magdalena River. There, he earned the reputation of being a shy child who wrote humorous poems and drew humorous comics. Serious and little interested in sports activities, his companions called him El Viejo.

García Márquez completed his first years of high school at the San José Jesuit College (now the San José Institute) since 1940, where he published his first poems in the school magazine Juventud. Later, thanks to a scholarship granted by the government, Gabriel was sent to study in Bogotá, where he was relocated to the Liceo Nacional de Zipaquirá, a city located one hour from the capital, where he would finish secondary school.

During his stay in the studio house of Bogotá, García Márquez excelled in several sports, becoming captain of the Liceo Nacional Zipaquirá team in three disciplines, soccer, baseball and athletics.

After graduation in 1947, García Márquez stayed in Bogotá to study law at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, where he had a special dedication to reading. The metamorphosis of Franz Kafka, particularly in the false translation of Jorge Luis Borges, was a work that inspired him especially. He was enthusiastic about the idea of writing, not traditional literature, but a style similar to his grandfather’s stories, in which “they inserted extraordinary events and anomalies as if they were simply an aspect of daily life.” His desire to be a writer grew. A little later, he published his first, The Third resignation, which appeared in the September 13, 1947 edition of the newspaper El Espectador.

Although his passion was writing, he continued with the law in 1948 to please his father. After the so-called “Bogotazo” in 1948, some bloody riots that took place on April 9, caused by the murder of popular leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, the university closed indefinitely and his pension suffered burns. García Márquez moved to the University of Cartagena and began working as a reporter for El Universal. In 1950, he finished his law studies to focus on journalism and moved back to Barranquilla to work as a columnist and journalist in the newspaper El Heraldo. Although García Márquez never finished high school, some universities, such as Columbia University, New York, awarded him an honorary doctorate in writing.

Source : wikipedia.org

Journalism

García Márquez began his career as a journalist while studying law at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. In 1948 and 1949 he wrote for El Universal in Cartagena. Later, from 1950 to 1952, he wrote a “capricious” column under the name “Septimus” for the local newspaper El Heraldo in Barranquilla. García Márquez noticed his time at El Heraldo, “I wrote a piece and they paid me three pesos for it, and maybe an editorial for three others”. During this time he became an active member of the informal group of writers and journalists known as Grupo Barranquilla, an association that provided great motivation and inspiration for his literary career. He worked with inspirational figures such as Ramón Vinyes, whom García Márquez described as an old Catalan who owns a bookstore in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

At this time, García Márquez also knew the works of writers such as Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner. Faulkner’s narrative techniques, historical themes and the use of rural locations influenced many Latin American authors. The surroundings of Barranquilla gave García Márquez a world-class literary education and gave him a unique perspective on Caribbean culture. From 1954 to 1955, García Márquez spent time in Bogotá and wrote regularly for El Espectador de Bogotá. He was a regular film critic who led his interest in the film.

In December 1957, García Márquez accepted a post in Caracas in the newspaper El Momento. He arrived in the Venezuelan capital on December 23, 1957 and began working immediately in El Moment. García Márquez also collaborated in the Venezuelan coup of 1958, which led to the exile of President Marcos Pérez Jiménez. After this event, García Márquez wrote an article, “The participation of the clergy in the struggle,” which describes the opposition of the Church of Venezuela against the Jiménez regime. In March of 1958 he made a trip to Colombia, where he married Mercedes Barcha and together they returned to Caracas. In May 1958, in disagreement with the owner of Momento, he resigned and soon became editor of the newspaper Venezuela Gráfica.

Politics

García Márquez was a “committed leftist” throughout his life, adhering to socialist beliefs. In 1991, García Márquez published “Changing the History of Africa”, an admirable study of Cuban activities in the Angolan Civil War and the great South African border war. García Márquez maintained a close but “nuanced” friendship with Fidel Castro, praising the achievements of the Cuban Revolution, but criticizing aspects of governance and working to “soften (the) tougher edges” of the country.

The political and ideological views of García Márquez were shaped by the stories of his grandfather. In an interview, García Márquez told his friend Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, “My grandfather the colonel was liberal, my political ideas probably came from him to begin with, because instead of telling me fairy tales when I was young, he gave me stories horrifying of the last civil war waged by the freethinkers and anticlerical against the conservative government. “This influenced his political views and his literary technique so that” in the same way that his writing career was initially formed in conscious opposition to the The Colombian literary status quo, the socialist and anti-imperialist views of García Márquez are opposed in principle to the global status quo dominated by the United States. “

Marriage and family

Garcia had Marquez meet Mercedes Barcha while she was at school; They decided to wait until it was over before they got married. When he was sent to Europe as a foreign correspondent, Mercedes waited for him to return to Barranquilla. Finally they married in 1958. The following year, their first son, Rodrigo García, was born, now a film and television director. In 1961, the family traveled by Greyhound bus throughout the southern United States and finally settled in Mexico City. García Márquez had always wanted to see the south of the United States because it inspired the writings of William Faulkner. Three years later, the couple’s second son, Gonzalo, was born in Mexico. Gonzalo is currently a graphic designer in Mexico City.

Later life and death

Decreasing health

In 1999, García Márquez was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. Chemotherapy provided by a hospital in Los Angeles proved to be successful and the disease went into remission. This fact led García Márquez to start writing his memoirs: “I minimized relations with my friends, disconnected the telephone, canceled trips and all kinds of current and future plans,” he told El Tiempo, the Colombian newspaper, ” … and I locked myself to write every day without interruption. ” In 2002, three years later, he published Living to Tell the Tale, the first volume of a projected trilogy of memories.

In 2000, his imminent death was incorrectly reported by the Peruvian newspaper La República. The next day, other newspapers re-published his supposed farewell poem, “La Marioneta,” but shortly after García Márquez denied being the author of the poem, which was determined to be the work of a Mexican ventriloquist.

He said that 2005 “was the first year of my life when I did not write a sentence, and with my experience, I could write a new novel without any problem, but people realized that my heart was not in it”.

In May 2008, it was announced that García Márquez was finishing a new “love novel” that had not yet received a title, which will be published by the end of the year. However, in April 2009, his agent, Carmen Balcells, told the Chilean newspaper La Tercera that it was unlikely that García Márquez would write again. This was questioned by the editor of Random House Mondadori Cristóbal Pera, who stated that García Márquez was completing a new novel entitled We will meet in August (In August we will see each other).

In December 2008, García Márquez told fans at the Guadalajara book fair that the writing had exhausted him. In 2009, responding to the claims of both his literary agent and his biographer that his writing career was over, he told the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo: “Not only is it not true, but all I do is write.”

In 2012, his brother Jaime announced that García Márquez suffered from dementia.

In April 2014, García Márquez was hospitalized in Mexico. He had infections in his lungs and urinary tract, and suffered from dehydration. He responded well to antibiotics. Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto wrote on Twitter: “I wish you a speedy recovery.” Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos said his country was thinking about the author and said in a tweet “All Colombia wants a quick recovery from the greatest of all time: Gabriel García Márquez.”

Death and funeral

García Márquez died of pneumonia at the age of 87 on April 17, 2014 in Mexico City. His death was confirmed by his relative Fernanda Familiar on Twitter, and by his former editor Cristóbal Pera.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos said: “One hundred years of loneliness and sadness for the death of the greatest Colombian of all time.” Former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe Vélez said: “Maestro García Márquez, thank you for all the time, millions of people on the planet fell in love with our nation fascinated by its lines.” At the time of his death, he had a wife and two children.

García Márquez was cremated at a private family ceremony in Mexico City. On April 22, the presidents of Colombia and Mexico attended a formal ceremony in Mexico City, where García Márquez had lived for more than three decades. A funeral procession carried the urn that contained its ashes from its house to the Palace of Fine Arts, where the commemorative ceremony was carried out. Previously, residents in their hometown of Aracataca in the Caribbean region of Colombia held a symbolic funeral.

Nobel Prize

García Márquez received the Nobel Prize for Literature on December 8, 1982 “for his novels and stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic combine in a world of richly composed imagination, reflecting the life and conflicts of a continent” . His acceptance speech was entitled “The Loneliness of Latin America.” García Márquez was the first Colombian and the fourth Latin American to win a Nobel Prize in Literature. After being a Nobel Prize winner, García Márquez declared to a correspondent: “I have the impression that when giving me the prize, they have taken into account the literature of the subcontinent and they have granted me as a way of granting all this literature.”