EPISCOPAL CHURCH, the Christian body centered in the United States that succeeded the Church of England in the American colonies after the Revolution.

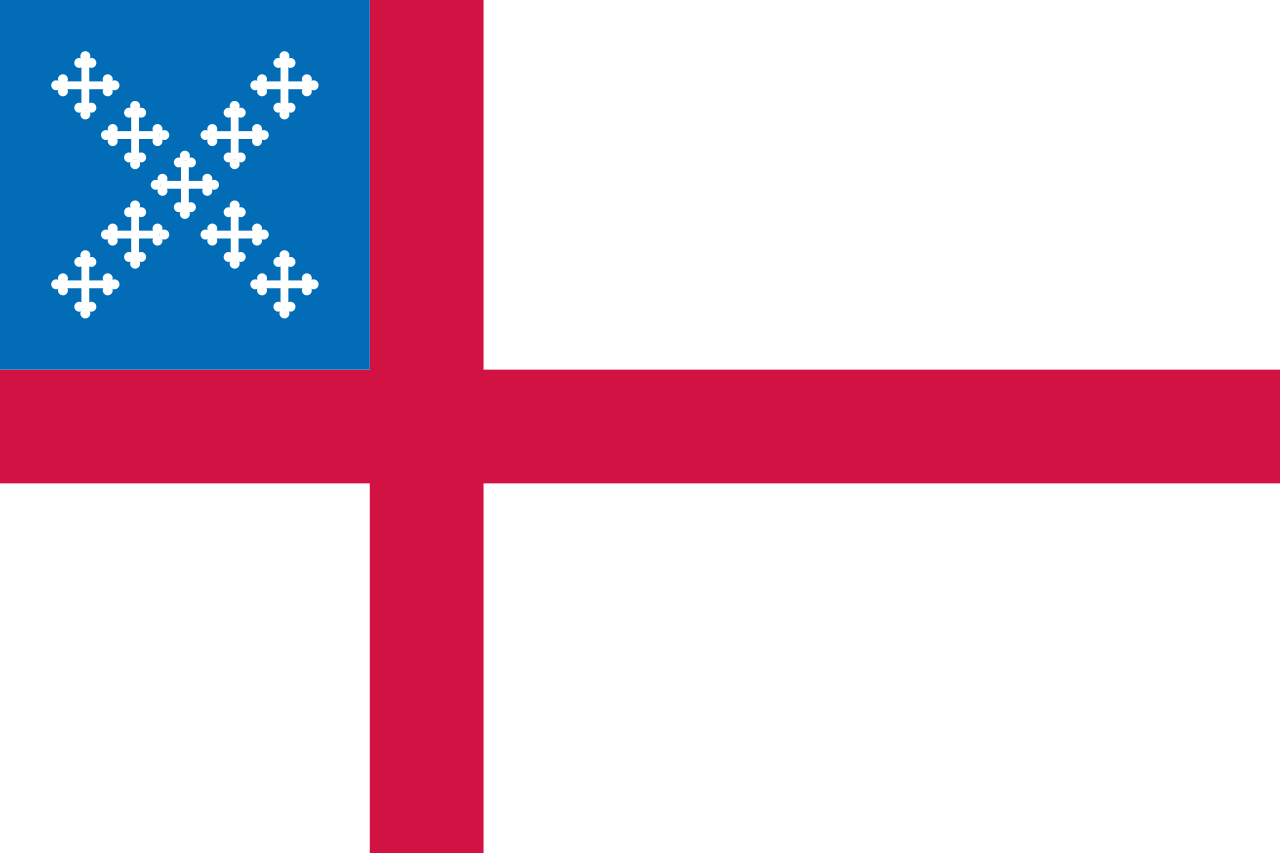

When the United States won political independence from Britain, the church in the new nation organized itself as the flrst independent Anglican body outside the British Isles. The church’s constitution calls it “The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, otherwise known as the Episcopal Church.” The name was chosen after the Revolution to describe the newly independent church: Protestant affirmed loyalty to the principles of the English Reformation; Episcopal affirmed the necessity of continuing the ancient Catholic ministry of bishops, whose authority is traced to the apostles. This rank of bishop had been abandoned by many other Protestant churches.

The constitution further declares the church to be a member of the Anglican Communion, a fellowship of Anglican churches around the world. all are linked to the Church of England in a common heritage of doctrine and worship, but the member churches are autonomous.

Source : wikipedia.org

ORGANIZATION AND GOVERNMENT

Parish and Diocese.

The local unit of the Episcopal Church is the parish. No longer a geographical entity, it is a community of Christians drawn together to worship, to help one another, and to offer the redemptive ministry to the secular community around them. The priest in charge of this congregation is the rector. He provides spiritual and sacramental ministrations and is the leader of the community in its worship and its programs of Christian education and evangelism. He may be assisted by ordained ministers, often known as curates, and by men and women who have been licensed as lay readers.

The parishes of a given area—once a whole state but now, with the growth in numbers, generally a portion of one state—are organized into a diocese. This area is under the supervision and authority of a bishop, whose duties and functions, though they sometimes appear to be largely administrative, are in fact primarily sacramental. The bishop ordains the clergy of tiıe diocese, flrst to the diaconate and then to the priesthood; administers confirmation; and generally fulfills a ministry as chief pastor and “father in God” to all his people. He may be aided in these responsibilities by assisting bishops, known as suffragans, or by a coadjutor bishop, an assistant already designated to succeed him in office.

The Episcopal Church has thus retained the basic parishdiocese organization found in Catholic Christendom throughout its history. It has, however, inevitably been modified, chiefly by adaptation to the circumstances of the American colonies and by the influence of distinctive American ways and principles. Democratic procedures, for example, have replaced older autocratic forms of parochial and diocesan government. In each parish an elective lay body of wardens and vestrymen exercises financial and administrative responsibility. They have the duty of choosing a rector, assisted by the bishop.

In the diocese, councils and committees of clergy and laity have a significant role in the church’s work. The legislative synod of each diocese is an annual diocesan convention, presided over by the bishop and consisting of all the clergy as well as representative lay delegates from each parish. Financing and carrying out an effective program of church work is the task of the convention. It also enacts canons, or regulations for the government of the diocese and its parishes, chooses deputies to the church’s national convention, and elects a bishop for the diocese in the event of a vacancy.

The National Church.

On the national level the supreme legislative body of the Episcopal Church is the triennial General Convention, meeting in a House of Bishops and a House of Clerical and Lay Deputies. Each diocese has equal representation in the latter—four priests and four lay persons. The convention’s canonical enactments are binding throughout all the dioceses. It alone has the power to alter the structure and constitution of the church, revise the Prayer Book or authorize alternative liturgical services for trial use, provide for missionary activity at home and abroad, authorize the Episcopal Church to participate in ecumenical ventures, and enlist the support of the whole church for programs of Christian education, evangelism, and social action.

The national executive officer of the Episcopal Church is the presiding bishop, elected by the General Convention from among the bishops, and responsible for leadership in developing the policy and strategy of the church. While he does not possess the ancient ecclesiastical jurisdictions of an archbishop, he is nevertheless the chief pastor of the Episcopal Church, and his personal influence is often stronger than that of a prelate with traditional archiepiscopal authority. The presiding bishop is ex officio president of the Executive Council, a body of bishops, priests, and lay persons elected to implement the programs of General Convention and to carry on the work of the national church between conventions.

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT

Colonial Beginnings.

Capt. John Smith told how services of the Church of England were begun in May 1607 at Jamestown, Va. For more than 20 years Anglican chaplains had accompanied English adventurers in their explorations and experimental settlements in North America, but it was here, in the flrst permanent settlement in Virginia, that the Episcopal Church began its long association with American life.

The colonists transplanted to Virginia much that was familiar at home, inelııding a church established by law and supported by grants of land and taxes on the principal crops. Similar establishments were attempted in the Carolinas and in Georgia, but Anglicanism was never as strong there as it was among the Virginians. In the middle colonies northward to New Jersey, Church of England congregations became numerous, though they possessed no special privileges. In New York, where a partial establishment was created in 1693 and financial support was given to ministers in several places, Anglicanism was vigorous and influential. Valuable land endowments granted to the famous Trinity parish, founded in 1697, made that church for many years a center of Anglican expansion.

In much of New England the Church of England encountered varying degrees of hostility. The ecclesiastical establishments in that area were those of English Puritans, men who had fled from the Anglican establishment at home.

The growth of Episcopal congregations, therefore, in Massachusetts and northern New England was very slow before the early years of the 18th century, and Anglicans were ahvays a small minority. Rlıode Island, however, founded on the principle of religious liberty, had a number of flourishing parishes. In Connecticut, where the principle of toleration was accepted in 1708, an Anglican church rivallng that of Virginia had appeared by the time of the American Revolution.

The Colonial Anglican congregations struggled under some severe handicaps. As friction increased during the 18th century between the colonies and the mother country, Patriots in some areas—particularly New York and New England— identified the Anglican parishes with English interests and suspected their members of Tory, or Loyallst, sympathies. Lack of funds often restricted church activities. Outside of Virginia, where the official establishment provided the same kind of assistance that Massachusetts gave the Puritan Congregationallsts, financial aid came chiefly from an English missionary society, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

Finally, the provision of clergy was often difficult. Opportunities for higher education were rare in the colonies, and a man generally prepared himself for the priesthood by studying with a learned clergyman. Eventually he had to undertake the long and expensive journey across the Atlantic to be ordained by an English bishop. Surprising as it may seem, the Church of England sent no bishop to the colonies. For 175 years Anglicans in America were in the anomalous position of belonging to an episcopal church with no resident bishops. The American parishes were under the tenuous jurisdiction of the bishop of London, more than 3,000 miles away.

Independence and Reorganization.

The American Revolution left many Anglican congregations shattered. In some northern areas, particularly where Episcopallans were suspected of loyalty to the English king, church buildings were destroyed and ministers banished. Persecution at the hands of zealous Patriots drove thousands of Loyallsts to seek refuge in Canada, the West Indies, or England. The majority of them were » church members, and among them were many clergymen. Their loss seriously weakerıed the church, and at the same time the cessation of financial aid from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel depleted its resources.

In the middle colonies and southward, on the other hand, clergy and church members were closely identified with the Patriot cause. Nevertheless, that did not save the parishes of Virginia and the Carolinas from acute distress. all public support ceased when the Revolution abolished the old ecclesiastical establishments.

In these circunıstances the achievement of a group of leading clerics and laymen was the more notable. Within a few years they had drawn the scattered congregations together into dioceses and united these in a national Episcopal Church, had bishops consecrated to ensure the continuance of the church’s historic order, and adopted a Prayer Book in which the distinctive Anglican faith and practice were maintained.

The Connecticut clergy were the leaders in securing the episcopate, electing Samuel Seabury their bishop in 1783. They sent him to England for consecration, only to learn that the English bishops could not legally consecrate a bishop unless he took an oath of allegiance to the crown. Seabury, therefore, was consecrated on Nov. 14, 1784, by bishops of the independent Episcopal Church of Scotland. Three years later when England’s ecclesiastical laws had been altered, the Archbishop of Canterbury consecrated William White as bishop of Pennsylvania and Samuel Provoost as bishop of New York. James Madison was later consecrated in England for Virginia, and in 1790 all four American bishops marked their independence by consecrating Thomas Claggett as bishop of Maryland.

The task of recovery was completed at the convention in 1789. A constitution was adopted for the organization of the church, and a set of canons for its governance. The Book of Common Prayer, with a few changes to relate it to the American scene, was authorized for use by all congregations. The church asserted that it was “far from intending to depart from the Church of England in any essential point of doctrine, discipline or worship.” Thus a church was formed that retained the essentials of its ancient heritage yet was free, selfgoverning, and adapted to the demands of its mission in America.

GROWTH IN THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES

Reawakened evangelism stirred nearly all American churches in the early years of the 19th century. In the Episcopal Church this was notable in the work of John Henry Hobart and Alexander Viets Griswold. Bishop Griswold rapidly built up the New England congregations, while Bishop Hobart multiplied the parishes of New York state. Clergy for this advance were trained at the two new theological seminaries, the General Theological Seminary, established at New York City in 1817, and the seminary founded at Alexandria, Va., a few years later.

Missionary Advance.

As the frontier expanded westward, the Episcopal Church followed—more slowly than some, for it lacked the easy adaptability to frontier conditions that other denominations possessed. Ohio had its first bishop, Philander Chase, by 1819. Jackson Kemper was made a missionary bishop for the old Northwest in 1835, and a few years later Leonidas Polk brought episcopal leadership to the Southwest. From then on the march was steady to the Callfomia shores. Nor was the church’s expansion more than briefly impeded by the Civil War. Episcopallans had not separated into northern and southern factions over the slavery question, as had some other American churches. When the Confederacy was formed, the southern dioceses organized into the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States. But as the northern Episcopallans did not recognize separation any more than the federal government recognized secession, in 1865 the dioceses were reunited.

Overseas missionary work began in both China and Liberia in 1835. William Boone was made Bishop of China in 1844, and in 1850, John Payne was consecrated for the Liberian mission. In Japan the educational mission of 1859 was the harbinger of evangelistic work that was begun when Japanese law allowed. The last decades of the century saw work under way in Alaska, Haiti, Brazil, the Hawaiian Islands, and, after the SpanishAmerican War, in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines.

A notable missionary achievement of the Episcopal Church was among the American Indians, particularly those of Nebraska and the Dakotas. Much of this was due to the labors of William Hobart Hare, a champion of the Indians and a constant advocate of justice for them, who was made missionary bishop of Niobrara in 1873—three years before Custer’s battle on the Little Bighorn. Ten thousand Sioux were baptized through the efforts of Hare and his fellow workers.

Evangelicals and Catholics.

Controversy in the Episcopal Chureh was frequent in the 19th century, much of it reflecting partisan struggles in the Chureh of England. The 18th century had seen a conflict between Low Churchmen, latitudinarian in their views and often holding little more than an undogmatic deistic creed, and High Churchmen. The latter maintained stoutly the divine nature of the church, the centrallty of the sacraments, the necessity of apostolic succession, and the authority of the ancient Church Fathers and tradition. By the early years of the 19th century the Low Churchmen had declined in numbers and influence. In their place were the vigorous Evangelicals, possessed of a Christcentered piety, moral earnestness, and devotion to the Bible as the source of spiritual illumination and a guide to conduct.

In the 1830’s at Oxford the old High Church principles were infused with new life by the dynamic teachings of John Henry Newman, John Keble, and others of the Oxford Movement. A decade later their influence was widely felt in the Episcopal Church. The movement recalled Anglicans to their negleeted heritage of Catholic doctrine and spirituallty, and did so with challenging implications for renewal in the life of the church. To many Evangelicals, the Oxford teachings seemed to threaten the priority of Scripture, raise the speeter of popery, and deny the gains of the Reformation. Particularly was this so when, as a result of the Catholic revival, the Prayer Book services were conducted with a new beauty and ceremonious order, the Holy Communion celebrated with unaccustomed frequency, the practice of individual, private confession revived, and a new emphasis laid upon the observances of the Christian year.

In the end the effect of the controversy was salutary. Both Evangelicals and High Church * men came to believe that when Anglicanism was faithful to the synthesis it sought to embody between Catholic and reformed elements, there was valldity in both positions. These controversies largely faded away in the 20th century Episcopal Church, partly as a result of liturgical renewal and partly as a result of wider appreciation of the nature of the Anglican tradition.

Statistics of the Membership.

In 1970 the Episcopal Church reported 3.5 million baptized members, of whom approximately 2.3 million were confirmed communicants. They belonged to some 7,500 parishes and missions located in more than 100 dioceses, including the missionary areas overseas. The strongest parishes are in the metropolitan areas of the United States, for Episcopallan strength is stili chiefly in urban centers. The elergy numbered about 12,00

DOCTRINE AND LITURGY

Doctrine.

The Episcopal Church shares the doctrinal heritage of the Church of England as do all the churches of the Anglican Communion. At the time of the Reformation no dogmatic confessional articles—such, for exanıple, as were characteristic of the Lutheran or Reformed churches—were adopted in England. The basis of doctrine was the scriptural faith, made explicit in the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds, reinforced by the theological statements of the general church councils of the 4th and 5th centuries, and set forth in the teachings of the ancient Fathers of the undivided church. The Thirtynine Articles of the reign of Elizabeth I did not constitute a full dogmatic confession but touched upon controversial matters. They were chiefly a defense against medieval Romanism or the views of such radical sects as the Anabaptists.

The principle of broad comprehension embodied in the Anglican Reformation has never been lost, and thus in the Episcopal Church considerable latitude of interpretation is tolerated in theology. This freedom has permitted a eloser understanding between Anglicans and both Roman Catholics on one hand and members of Protestant churches on the other. It has also made it easier to seek new insights into ways in which the scriptural faith may be proelaimed effectively in the changing human scene.

Liturgy and Worship.

The official services of the Episcopal Church are set forth in the Book of Common Prayer. It contains the Daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer, together with the Psalms to be used at each service; the Holy Communion, with appropriate collects, epistles, and gospels for the observances of the Christian year; Holy Baptism, rites for other sacraments, and the pastoral offices; the ordination services; and forms of prayer and thanksgiving for many needs and occasions. The liturgical antecedents of the Book of Common Prayer are found in the ancient and medieval forms of Christian worship, revised and translated in the English Prayer Books during the course of the Reformation.

Adopted in 1789, and containing slight revisions of the Church of England services as they had been used in the colonies, the American Prayer Book was subsequently revised in 1892 and 1928. On both occasions the changes were in the interests of spiritual enrichment and greater flexibility of use. By 1965 the Prayer Book was again in process of revision, and this time far more extensive changes than those of earlier years were being introduced.

The modern revision of the Prayer Book is one aspect of the demand for church renewal that has swept the Episcopal Church, in common with most of Christendom, during the second half of the 20th century. Drastic changes in the old ways of Christian worship are ardently advocated as essential to the total reinvigoration of the church in its mission and unity, and in its relevance to the contemporary social and cultural environment. Liturgical experiment, therefore, has become common, not only in the Protestant churches, but also within Roman Catholic Christendom.

Revolutionary changes in customs of worship long familiar to Episcopallans inelude greater participation of the laity, new ceremonies to symbolize the total offering of men’s life and work in a secular world, updated language that refleets the vocabulary of the 20th century, a new informallty of prayer, music, and action, and the use of biblical material that speaks more plainly to a generation almost illiterate in the Scriptures.

In 1964 a change was made in the constitution of the Episcopal Church, allowing the General Convention to set forth experimental services for trial use as alternatives to those of the Book of Common Prayer. By 1967 the first of these, a Liturgy of the Lord’s Supper, was ready, and by 1970 a complete book of “Services for Trial Use” had been authorized. This contained revisions of all the rites of the Prayer Book, and, in some cases, offered optional forms for further experimental use

ECUMENISM, SOCIAL ACTION, AND REFORM

Ecumenism.

The Episcopal Church, like other Anglican churches, has been involved in the movement for church unity ever since its House of Bishops in 1886 appealed to Christians to seek reunion by a return to “the principles of unity exemplified by the undivided Catholic Church during the first ages of its existence.” The bishops declared that four elements of Christian faith and order were essential to the restoration of unity: the Scriptures, the Nicene Creed, the sacraments of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, and the historic episcopate. These formed the points of the famous “Lambeth Quadrilateral,” affirmed by all the Anglican bishops at one of their periodic Lambeth Conferences, held at the residence of the archbishop of Canterbury.

These points are generally regarded as the necessary basis of unity in any ecumenical negotiations involving Anglican churches. Common possession of these elements, for example, has made possible the establishment of full communion between the Episcopal Church and the Old Catholic Churches of Europe, the Polish National Catholic Church in America, the Lusitanian Church of Portugal, the Spanish Reformed Church, and the Iglesia Filipina Independiente in the Philippine Islands. The Episcopal Church has formally recognized the ministry of those episcopally consecrated and ordained within the Church of South India, and a limited measure of intercommunion is authorized.

Ecumenical conversations with a number of American Protestant churches have occupied Episcopallans for many years. In 1962 the Episcopal Church joined the Presbyterian Church, the Methodist Church, and the United Church of Christ in forming the Consultation for Cfyırch Union. The purpose of this joint efîort was to explore the ways in which their respective heritages might be united in a church “truly Catholic, truly Reformed, and truly Evangelical.” Subsequent to 1962 a number of other churches entered the consultation. A half dozen years of study and conference produced the first tentative plans for eventual union, and an experimental liturgy of the Holy Communion for use, where authorized, in the participating churches. The Episcopal Church has also inaugurated conferences with the Roman Catholic Church.

Social Action.

After World War II, concern mounted in the Episcopal Church about the evils of poverty, racial segregation, and discrimination of all sorts. The church’s program of urban work was strengthened, presenting the Gospel in terms of social action that witnesses to a profound Christian concern with the conditions under which thousands suffer in the cities.

A revolutionary commitment to social action was made at the General Convention of 1967: a program to assist the national black community in selfdetermination and development was adopted. The sum of $3 million was allotted annually during the triennium for this and other efforts to assist disadvantaged minority groups. Despite controversy over some aspects of the program, the Episcopal Church as a whole accepted its responsibilities, and the venture was reaffirmed at a special convention in 1969.

Reform.

The revolutionary spirit in the contemporary world has attacked the entrenched institutions of what is called “the Establishment” —whether political, military, academic, or ecclesiastical. Demands for sweeping reforms in the life of the church have been insistent, and the Episcopal Church has felt the force of this challenge as keenly as have other historic bodies.

In addition to those aspects of liturgical renewal and social action that embody the spirit of reform among Episcopallans, successful attempts have been made to introduce greater simplicity and flexibility into the canonical and administrative structures of the church. A new emphasis upon the church as community rather than institution has become widespread.

To meet the challenges of the secular world, concepts of the priestly vocation and its exercise have been broadened, and the character of theological education in the seminaries has been affected by the new patterns of ministry. Nonparochial clergy have increased in numbers. These are priests who are not involved in parochial responsibilities but seek new forms of ministry in education, social action, welfare services, and other areas of human concern.

Some observers have predicted that these and other innovations in the worship and work of the church are signs of a 20th century reformation that might eventually be as farreaching as that of the 16th century.