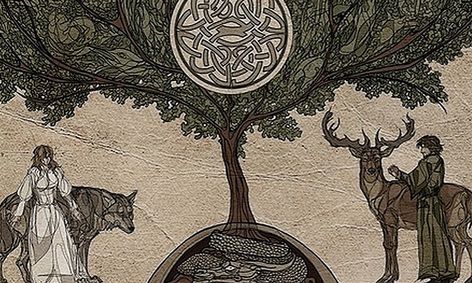

CELTIC MYTHOLOGY, The mythology of the Celts is perhaps best known in modern times because of its influence on Irish and Welsh folklore and literature.

However, the term “Celtic mythology” covers the mythology of peoples who once inhabited much of continental Europe as well as the British Isles. Celtic mythology is steeped in magic and the supernatural. Neither the Celts nor related barbarians possessed philosophical or ethical concepts of religion. Rather, their concern lay in the proper functioning of magic, exerted through ritual, to procure prosperity in the land, freedom from disease, and victory in war. Thus Celtic paganism may best reflect the nature of what ali European peoples must once have held sacred, and there are many links with Italic, German, and even Aryan mythology.

The Structure of Celtic Mythology.

Among the Celts, the Otherworld seems to have been conceived as a magical counterpart to the world of men, with a similar social structure and possibilities for overlordship. A signifîcant feature of the Celtic deities was their distinctly local character. Each tribe possessed its one allpowerful god, who was an eponymous ancestor (having the same name as the tribe), protector, and provider. Some deities obtained a more universal recognition, but in general uıe welfare of any one Celtic tribe was influenced by its particular local god. Many of these gods, often of immense size and appetites, had similar attributes. Thus Dağda, “the good god” in Ireland, may be compared with Esus, “master” in a beneficent sense, in Gaul.

Dağda, as the allcompetent father, protector, and benefactor of the tribe, represents the basic type of Celtic male deity. He is pictured with a neverempty cauldron, signifying eternal plenty and fertility. Magical cauldrons symbolizing abundance were attributed to other gods as well.

Each local god possessed allembracing powers, and there were no gods with powers limited to a single focus, such as war, wisdom, or beauty, as in Greek and Roman mythology. However, there is evidence, particularly in Ireland, of an association of gods similar to the Greek and Roman pantheons. This. association was known in Ireland aş the Tuatha De Danann, or “the peoples of the goddess Danu.” Dağda, Gobniu, and another Irish god, Lug, belonged to this group. According to legend, the Tuatha De Danann defeated older established deities, particularly through the prowess of these three gods. Overcome in turn by the Milesians, the forerunners of the presentday Irish, the Tuatha De Danann retreated to the hills and became associated with the fairy folk so noted in Irish folklore today.

Goddesses, while mates of tribal gods, also had special relationships with tribal kings, particularly in Ireland. At the beginning of a reign, the goddess appeared as a beautiful maiden who accepted the youtiıful king. But with the decline of the king’s physical powers, the goddess awaited his death in the guise of a dreadful has. The mythological stories around this theme imply the king’s ritual death by burning or stabbing. There are indications, also, that goddesses were identified more closely with natural topography or territory than with society. The same goddess might have several names in reference to her particular role. As deathforeboding hag, her names are always horrific compared with those appropriate for other functions. Thus there were Nemain (panic), Morrıgan (queen of demons), and Badb Catha (battle raven). On the other hand, the river goddess names Boann (Boyne) and Sequanna (Seine) imply fruitfulness. Dedications to Matronae, “the mothers,” show plaeid seenes of three seated women surrounded by baskets of fruit, small animals, and infants. The number “three” was regarded as sacred and having magical powers.

Sacred Festivals.

The major Celtic festivals, especially in Ireland, commemorated the change in seasons from warm to cold. Samain, celebrated on the day that is November 1 in the modern calendar, was the greatest festival in Ireland, marking the end of one year and the beginning of the next. Rituals were undertaken to ensure a prosperous year. Perhaps the most significant period of this festival took place the preceding night, corresponding to Halloween, when it was believed that the world of men was overrun by the forces of magic. At the festival of Samain the marriage of Dağda with Morrıgan or with Boann was celebrated.

The second major Irish festival was Beltine, celebrated on the first of May at the beginning of the warm season. Great fires were kindled at this festival, probably dedicated to the god Belenus, who was associated with the welfare of sheep and cattle. Other seasonal festivals were Imbolc, celebrated on February 1, and Lugnasad, on August 1. Imbolc, perhaps particularly connected with sheep tending, corresponds to the Christian feast of St. Brigid or Brigit. The Celtic Brigit, a daughter of Dağda, was a powerful fertility goddess. Lugnasad, founded by Lug in honor of a goddess, stili survives.

Sacrifices were prominent in Celtic ritual, and human and animal sacrifices took place at the sacred festivals. One Irish myth concerns the sacrifice of the son of a sinless couple to rnake amends to the gods for an unfortunate marriage between a king and a foreign woman. As the boy is about to be sacrificed, a woman appears leading a cow, which is offered up instead.

The practitioners of Celtic ritual and magical lore were most widely known as druids. The druids held a dominant position in Celtic soci|ty, for it was they who invoked the magical powers to ensure prosperity and success. Descriptions of hideclad druids undergoing trances in order to forecast events resemble accounts of shamans in other cultures—for example, the medicine men of the North American Indians.

After the inclusion of much Celtic territory in the Roman Empire, Celtic deities were often identified with Roman gods. As a result, Roman sculplure was adapted to the portrayal of largely native deities. Moreover, many Latin dedicatory inscriptions incorporating a great number of Celtic names have been found in the British Isles, the Iberian Peninsula, and the Rhineland.

Although the Celts once covered a large area of the European continent, much of the information about their mythology comes only from the British Isles, particularly Ireland and Wales. Nevertheless, it is clear that the elements of Celtic mythology relate to a common IndoEuropean heritage from which much of Western mythology derives.