What are the causes, preparations of Franco-Prussian War? The Franco-Prussian War summary, effects and results. Information on Franco-Prussian War.

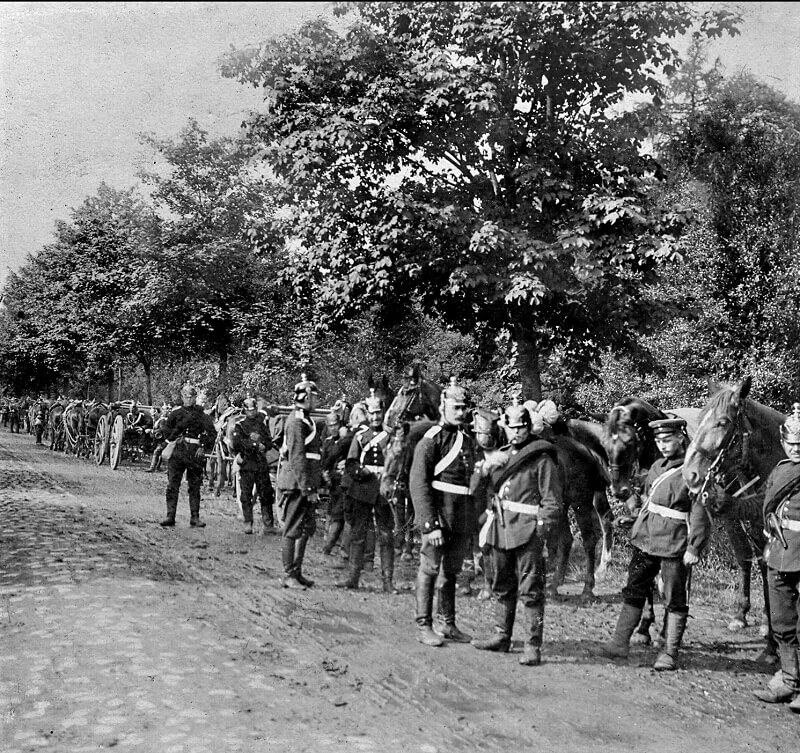

Franco-Prussian War; a conflict in 1870-1871 in which a coalition of German states decisively defeated France.

Causes.

The rapid, spectacular victory of Prussia over Austria in the Seven Weeks’ War of 1866 disturbed the European balance of power. Earlier, the France of Napoleon III had dominated Europe. French military successes in the Crimea and Italy had combined to offset the internal weaknesses of Napoleon’s Second Empire. Prussia, however, was emerging as the senior partner in the Germanic Confederation. Prussia’s victory in 1866 confirmed its leadership of Germany and posed a serious threat to French supremacy in Europe.

Source : wikipedia.org

The French recognized that the rise of Prussia posed a threat to their position, and a vigorous foreign policy appealed to the imperialists in parliament, who saw such a policy as a recompense for liberal domestic concessions. In Prussia, too, elements of both political extremes welcomed the Franco-German clash. Conservatives hoped to avenge Prussia’s defeat by Napoleon I in 1806 at Jena, while many liberals feared French encroachments on the Rhine.

Many Prussians, among them Chief of the General Staff Helmuth von Moltke, had considered war with France inevitable ever since the Rhineland crisis of 1831. Nor had French foreign policy in the 1850’s and 1860’s allayed Prussian uneasiness. French intervention in Italy in 1859 seemed bellicose and opportunistic. The unsuccessful attempt by Napoleon III in 1867 to obtain Luxembourg appeared directly hostile.

The immediate cause of war in 1870 was in the tangled threads of Spanish politics. The expulsion, in 1868, of the promiscuous Queen Isabella II had left the Spanish throne empty. The Spanish council of ministers sought a suitable successor, and Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern, a distant relative of the Prussian King, seemed a likely candidate. Prussia’s Chancellor Otto von Bismarck saw that a German prince on the throne of Spain would greatly strengthen Prussia’s position in any future conflict with France. After some indirect pressure from Bismarck, Leopold agreed to accept the throne.

The news leaked out toward the end of June and produced a frenzied response from the French foreign minister, Antoine de Gramont, who accused Prussia of deliberately attempting to upset the balance of power. Gramont refused to accept Leopold’s resignation as sufficient, and demanded from King William I of Prussia, who was at Ems, a declaration that no Hohenzollem candidacy would be renewed. William declined. Although he had never been particularly in favor of Leopold’s candidature, he would not be humiliated by the French. A telegram giving details of William’s interview with the French ambassador was sent to Bismarck, who edited it to make the ambassador appear importunate and his dismissal curt.

Source : wikipedia.org

Preparations.

The publication of the Ems telegram produced the reaction Bismarck wanted. On July 18, 1870, the French formally declared war, mobilization having begun late the previous day. The war was greeted with enthusiasm by many Frenchmen. The French Army, containing a high proportion of professional, experienced veterans, was generally supposed to be invincible.

This confidence was tragically misplaced. Military reforms undertaken after the shock of 1866 had, it is true, created the garde mobile as an army reserve. There had also been technical innovations, notably the introduction of the breech-loading chassepot rifle and the mitrailleuse machine gun. The usefulness of these reforms and innovations was, however, limited. The garde mobile, in the few areas where it did in fact exist, was so badly trained as to be worthless. The chassepot and the mitrailleuse, while excellent weapons, would suffer from faulty tactical employment in the war, and were of limited value due to lack of artillery support.

The most crucial flaw in the French war machine lay, however, in its controls. French involvement in colonial campaigns had led to neglect of the detailed planning essential for mobilization against a European enemy. The main task of the French general staff was to gather intelligence; it did not formulate war plans.

But the Prussian general staff, like the rest of the army, had profited from the experience of 1866. Concise and accurate mobilization plans aimed at a swift, largely railway-borne, concentration between the Rhine and the Moselle. Moltke initially envisaged a double enveloping movement, for which the Prussian Army was divided into two wings. The right wing, commanded by Prince Friedrich Karl, comprised the Prince’s own Second Army and Gen. Karl von Steinmetz’ First Army. This force formed up northeast of Saarbrücken. The left wing, comprising Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia’s Third Army, which included most of the allied German contingents, concentrated in the Bavarian Palatinate.

The War.

Faced with this double threat, the seven corps that initially constituted the French Army formed a screen covering the frontier. A brisk French offensive by part of this force reached the high ground west of Saarbrücken, but accomplished nothing. The French Army then regrouped into two main bodies; Marshal Bazaine commanded the left wing, and Marshal MacMahon the right. Each wing comprised three corps. The imperial guard, forming a corps of its own, was kept by Napoleon III in reserve.

Source : wikipedia.org

On August 6 Bazaine was dislodged from his position west of Saarbrücken, but fell back toward Metz in relatively good order. On the same day MacMahon was severely mauled some 40 miles (64 km) to the southeast, at Worth, losing 20,000 men, and he retreated through Saverne toward Chalons-sur-Marne. Bazaine, meanwhile, withdrew into the fortress of Metz. On August 12, shortly before Napoleon’s departure for Chalons, Bazaine was given command of the Army of the Rhine, but his courage was no substitute for good staff work or strategic ability.

To prevent the encirclement that appeared to him imminent, Bazaine, on August 15, ordered a withdrawal across the Moselle to the west. His army was scarcely clear of Metz when two German corps, under the mistaken belief that they were engaging the French rear guard, crashed into Bazaine’s flank from the south. There ensued a swirling 2-day action on the bare uplands around Gravelotte and St.-Privat, in which the Army of the Rhine successfully beat off Prussian attacks but failed to clear the Verdun road. On August 19, Bazaine retired once more to Metz.

MacMahon, in the relative security of Chalons, reassembled his army. Having been reinforced, he set out northeast on August 23, hoping to join Bazaine, who, he assumed, would try to break out of Metz toward Sedan or Ste.-Menehould. To deal with MacMahon, Moltke formed the Army of the Meuse from three corps of the Second Army. While the remainder of the Second Army, together with the First Army, covered Metz, the Third Army and the Army of the Meuse swung north in pursuit of the Army of Chalons. MacMahon, urged on by an anxious government, was encircled at Sedan, where, on September 1, his army was all but annihilated. Napoleon himself, after a desperate effort to find death in battle, surrendered. With him, the bulk of MacMahon’s army, 104,000 men and over 400 guns, passed into Prussian captivity.

The disaster at Sedan had a shattering effect upon Paris. The Second Empire was replaced by a government of national defense, headed by Gen. Louis Jules Trochu. The capital came under siege on September 20. While eight German corps besieged Paris, the First and Second Armies contained the Army of the Rhine within Metz. An attempted breakout on September 1 proved a costly failure. Rations within the fortress ran low, and morale ebbed. In October the weather broke, and the army languished in the mud. On October 29, Bazaine capitulated with 172,000 men and over 1,400 guns.

The government of national defense still had at its disposal considerable manpower, as well as some commanders of talent. The newly formed Army of the Loire and forces in the north and southeast fought on with some success and many defeats. Francs-tireurs harried the enemy.

Paris remained besieged; food was scarce, sorties proved ineffective, and the defense was hampered by political unrest. Paris was bombarded for three weeks. On January 28 an armistice was signed. The forts around Paris surrendered, and the city paid an indemnity of 200 million francs. By the Treaty of Frankfurt, France lost most of Alsace-Lorraine and had to pay an indemnity of 5 billion francs.

Source : wikipedia.org

Results.

The effects of the Franco-Prussian War were far-reaching. In military terms, the war demonstrated the invalidity of the purely professional army. The nation in arms, tightly controlled by a careful general staff, was the only viable military organization for the future. Politically, the war set the seal on German unity, and the creation, on Jan. 18, 1871, of the German Empire, with William I at its head, assured Prussia of hegemony within Germany.

The Third Republic, which emerged from the postwar maelstrom within France, reflected all the stresses that had plagued the Second Empire. The lost provinces of Alsace-Lorraine made lasting peace with Germany unlikely. The events of 1870-1871 ensured that France and Germany would enter the 20th century in an atmosphere of mutual animosity, with military machines largely geared to the renewal of conflict across the Rhine.