Many Catholics formerly identified the liturgy with mere ceremony, or viewed it as a code of laws governing the external performance of sacred services.

Still others identified it with vestments, or Gregorian chant, or church music. But ali these views were superficial and failed to touch upon the substance, the reality of what the liturgy is.

Nature of the Liturgy.

The liturgy springs from what the church itself is, and since it is impossible to define the church adequately, it is equally inıpossible to define the liturgy. Like man himself the church resists or transcends definition. The church is simultaneously structured community ancl communion, event and activity; it not only is, it does.

Among its activities is the celebration of the liturgy, and this activity, as the Constitution on the Liturgy emphasizes, is the summation and synthesis of ali the other activities of the church. It is the expression of the church’s whole life, and that life is directed toward making Christ present in the world. From the very beginning, the church has recognized that the liturgy is the principal means of accomplishing this. The liturgy gives glory to God and brings peace, that is, salvation, to men. Neither one of these activities is isolated from the other: the church believes that the very act of saving men gives glory to God; the act of glorifying God brings salvation to men.

Thus liturgy is an act of worship, but it is distinguished from worship in the broad sense. Worship is the response that man makes to God for ali that God is and has done. Man gives recognition to God in the form of praise, thanksgiving, petition, sacrifice: these may be expressed publicly or privately, alone or in community, inwardly felt or outwardly expressed. Regardless of tiıe manner in which these prayers are offered, they are equally acts of worship. Liturgy, on the other hand, is public worship, not by any one man or group of men, but by the community that is the church.

Since the liturgy is the embodiment of the church’s attitude toward God—that specialized form of worship that involves the entire community—it is always outwardly expressed. A liturgy that is purely internal is, therefore, a contradiction. Similarly, a liturgy that is only external is an empty formality. Liturgy is an action, the action of Christ in the church, an action that employs signs and symbols but that is not imprisoned by them, an action that does what it signifies but does far more than the signs—the words and the actions— can adequately convey. It is an action that involves the whole man, his mind, heart, and will, body and emotions.

Just as liturgy is not simply worship, it is inadeqnate to define it as rite, although these terms are often used interchangeably. “Roman Liturgy” and “Roman Rite,” for example, are used to express the same thing. Strictly speaking, however, the Roman Rite is only one of the many ways of celebrating the liturgy. Since the liturgy basically celebrates the mystery of salvation, or the redemptive activity, in symbolic form, the form may vary from one rite to another, but the celebration is always the same. Thus there are many rites, but only one liturgy, one act of the church. The death of the Lord is proclaimed one way in Alexandria, another in Rome, and stili another way in Antioch: the words and the gestures are quite distinct, but the drama is unchanging.

In ali the rites the mystery of salvation is enacted principally through the Eucharist, or Mass, then through the other sacraments, and finally through the Divine Office, which is the public prayer of the church. Although this article is primarily concerned with the Roman Rite—that form of the liturgy which had its beginnings at Rome but spread throughout the world to become the most prevalent of ali the Christian rites—the theology outlined concerning the lit*urgy is equally applicable to ali the rites.

The Sacraments.

The Sacrament of the Eucharist, which is the Mass, is the principal sacrament. The other six sacraments are closely related to the Eucharist: Baptism and Confirmation equip a person to celebrate the Eucharist by making him a member of the church; Penance reconciles the Catholic to the church after he has fallen into sin; Matrimony is the sign of the union between Christ and His church; the Anointing of the Sick is the sacrament that restores the sick man to health so that he may again participate in the Eucharist with his brethren in the church; Holy Orders makes a man capable of performing the ministry of the Eucharist for his felİ0’W Christians.

Like the Eucharist these sacraments are acts of public worship, and together with the Eucharist form the most important part of the liturgy. St. Augustine calls the sacraments the “visible word,” because they are made up of words and actions: the words give meaning to the actions and, in a very real way, are actions in themselves.

The sacraments are effective signs of God’s action in Christ and man’s response to that action, also in Christ. Unlike the commentators of the recent past, modern theologians stress the personal aspect of the sacraments. They view the sacraments, not as the action of God alone but as the joint action of Christ in His church, of the priest who celebrates them, and of tiıe faithful Christian, the concelebrant, who takes part in them. Contemporary theologians point out that men do not just receive the sacraments, they participate in them.

The Principal Sacrament.

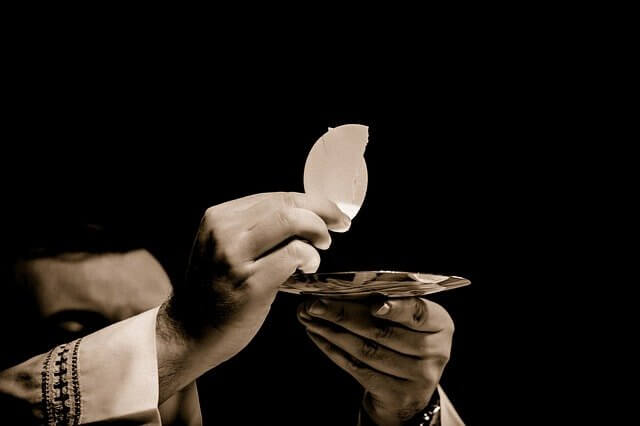

The Eucharist, or Mass, is the sacred rite that reenacts the Last Supper. Thus the Mass is a sacramental offering of sacrifîce to God. The Constitution on the Liturgy beautifully expresses the meaning of the Mass: “At the Last Supper, on the night when he was betrayed, our Saviour instituted the Eucharistic sacrifîce of his body and blood. He did this in order to perpetuate the sacrifîce of the cross throughout the centuries until he should come again, and so to entrust to his beloved spouse, the Church, a memorial of his death and resurrection: a sacrament of love, a sign of unity, a bond of charity, a paschal banquet in which Christ is received, the mind is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given us.”

Divine Office.

The Divine Office, or daily prayer of the church, is next in importance after the Eucharist and the other sacraments. It is not, however, a separate or isolated activity. The Office actually complements the sacraments and continues the work of the redemption because it shares in the prayer of Christ.

The Constitution on the Liturgy describes the prayer of Christ as: “Christ Jesus, high priest of tiıe new and eternal covenant, taking human nature, introduced into this earthly exile that hymn which is sung throughout ali ages in the halis of heaven.” This hymn of praise and thanksgiving goes on for ali eternity. Christ is its first and greatest celebrant. But He does not sing alone—He associates ali creation with Him in singing it, especially the rational, human part of creation. This hymn takes many forms: it resounds in tiıe Mass and the sacraments, but it finds more direct and ordered expression in the Divine Office. This is done by means of psalms, hymns, and canticles.

Originally the Office was the prayer of the layman. The clergy did not even attend it. It was divided into two parts, morning and evening prayer, or Lauds and Vespers. In the course of centuries, however, the Office, like the Mass, became a clerical specialty. Unlike the Mass it remains so even today. In theory it is “the prayer of the church,” but in practice it is not. A complete and radical reform of the Office has been called for by many in order that it keep pace with the reform of the Mass and the sacraments.

Liturgical Year.

The celebration of the Mass and the Office is set in a framework that is known as the liturgical year, or the year of tiıe church. This year does not correspond to the current calendar year, but rather turns about the feast of Easter, or, as it was called in ancient times, Pascha, tiıe paschal feast. The preparation for Easter and the celebration and the prolongation of the feast take up the greater part of the year.

The purpose of the liturgical year is to commemorate and celebrate the mystery of the redemption. Even the feasts of Christmas and Epiphany are regarded more as celebrations of the redemptive event than as commemorations of the temporal birth of Christ. The feasts of the Blessed Virgin and the saints, which round out the year, are in the main much later additions to the original nucleus. They too derive ali their meaning from the redeeming work of Christ.

Sunday, the day of the Lord, is the pivot on which the liturgical year turns, precisely because Sunday is the day on which the Lord rose from the dead and sent the Holy Spirit upon the church. In a most complete way it is the day of the resurrection, recalling not only tiıe event itself but ali its consequences.

Through the liturgical year the redemptive events, or mysteries, as they are called, are made present in such a way that the faithful may make contact with them and be filled with the graces these mysteries contain. The sacred mysteries of the life, deatiı, and resurrection of Christ reach the faithful through the symbolic commemoration of these events. By means of the readings, prayers, and ahants of the Mass and Office tiıe inward reality of these mysteries is made clear, and the faithful are stimulated to live by these mysteries, to reproduce them in their lives.

Ali the liturgy revolves around the Paschal Mystery, the mystery of the deathresurrection of Christ. Pope Pius XII’s encyclical Mediator Dei (On the Sacred Liturgy, Nov. 20, 1947) points out that “the liturgical year is Christ himself.” The liturgical year is a natural device that assures the remembrance of the great events of salvation. But these events cannot be separated from Christ, who accomplished them.

THE HISTORY OF THE LITURGY

The Institution of the Eucharist.

The Eucharist, or Mass, is always the reenactment of the Last Supper, or the Lord’s Supper. Whether or not the Last Supper was a Passover celebration is a question that engages scholars, but one that will probably never be resolved satisfactorily. It is clear, however, that the supper occurred during the time of year, and in the same week, that the Jews celebrated Passover, and it is probable that the meal was held in the atmosphere of the paschal feast.

In Christ’s time, just as today, the Jews commemorated the deliverance of their ajıcestors from Egypt at the Passover feast. By participating in this annual memorial of the Exodus the Jew could share in the experience of deliverance that his fathers had enjoyed; at the same time, he could look forward to a fuller deliverance, a more perfect Exodus to come. This spirit undoubtedlv permeated the thinking of the disciples at the Last Supper and, indeed, was carried över into the Eucharistic feast celebrated by the early Christians.

The events that occurred at the Last Supper are recorded in the New Testament in the writings of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Paul. None of these accounts teli exactly what Jesus said or did because the evangelists were preoccupied with the meaning the Eucharist had to the Christian community rather tiıan detailed history. In fact, since tiıe Eucharist was celebrated each week long before the evangelists wrote their accounts of tiıe Last Supper, many scholars believe that these accounts were transcriptions of the Eucharistic celebration of the period.

Although the accounts are not in complete harmony, ali four agree that during tiıe meal Christ took a piece of bread into his hands, pronounced the customary thanksgiving and blessing över it, broke it, and then, as he gave it to his disciples, said: “Take and eat, this is my body.” After the meal had been eaten, Christ took the “cup of blessing,” pronounced a longer blessing över that, and as he passed it around to his disciples, said: “Take and drink, this is the cup of my blood,” or “This is the new covenant in my blood.”

Through this series of actions and words Christ aeted out a prophecy or parable in the Hebraic style. He symbolically dramatized his coming sacrifice and, at the same time, gave it meaning by interpreting it through his words. Although Christ’s actions were those of any ordinary head of a house at such a gathering, his words imparted deeper meaning to his acts, and his disciples’ response—their taking and eating, their taking and drinking—completed the meaning of both his words and his actions.

The Eucharist as a Memorial.

The word “memorial” had much more meaning to the Jews of Christ’s time than it does to men of the 20th century. Today the word “memorial” has a purely subjective connotation: it implies someone or something no longer present that is recalled to mind through an effort of will. To the ancient Jew, on the contrary, the liturgical memorial was an objective representation that made the t>ast event present in some way. The New Testament clearly indicates that Christians of the apostolic age believed that they encountered the Risen Christ in the Eucharistic feast.

Neither Matthew nor Mark mentions Christ’s command “do this in commemoration of me,” but both Luke and Paul do. This discrepancy has led some scholars to deny that Jesus ever said these words. It is highly signifîcant, however, that they appear in St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians (11:25), which is the oldest account. In this Epistle, Paul reports that Christ said: “Do this … as a remembrance of me,” and adds “As often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the death of the Lord until he comes.” Paul goes on to say that he received this account “from the Lord.”

This statement shows that the early Christians believed that Christ had commanded His disciples to repeat His supper. Whether or not Christ actually pronounced these exact words, then, is purely an academic question. The disciples of Jesus Christ acted as though He had said them.

How exactly they obeyed His command is uncertain. It is known that the Eucharist was connected with the ordinary family meal for some time. On the first day of the week the early Christians gathered in the home of one of their members, usually a house with a room of sufficient size to accommodate such a gathering. Sunday was a day of great significance to the early Christians; not only had the Holy Spirit been sent to the Apostles on this day (that is, Pentecost), but more importantly it was the day of the Lord’s Resurrection. Thus the early Christians prayed in the synagogue on the Sabbath, the last day of the week, and on the first day of the week they commemorated the Risen Lord’s sacrifice at a fraternal meal at which the bishop officiated.

St. Paul’s words, “In the same way, after the supper, he took the cup . . .,” indicate that at first the blessing of the bread was separated from the blessing of the cup by the actual meal. Before long, however, the two consecrations were joined together, and the prayer or blessing över the cup became the blessing for both. The actual meal, or agape, either preceded or followed the Eucharist. At one time it was believed that the first part of the Eucharistic service that is now called the Liturgy of the Word, was derived directly from the synagogue service. Modern scholars, however, are more cautious about this assertion, and suggest that, at most, the synagogue service only influenced the form of the Liturgy of the Word.

The Eucharist as a Formal Liturgical Service.

By the end of the İst century the fratemal meal, or agape, became totally separated from the Eucharistic service. The increase in the number of Christians with the resulting problems and abuses contributed to this development of the Eucharist as a formal liturgical service. Another factor was the inability of the nonJewish, or Gentile, converts to relate the Eucharist to an ordinary meal. Unlike the Jews, their traditions did not include a, family meal of religious significance.

In spite of this, the Eucharist continued to be regarded as a meal—a very speeial, stylized meal at which the Lord is the host, inviting men to sit down with him at table. The altar on which Christ’s sacrifice on the cross is reenacted is not an altar in the pagan sense: it is the table of the Lord on which is offered, not a bloody victim, but something that is primarily lifegiving food. Like other food, the bread and wine of the Eucharist are blessed and eaten. The Eucharist is a sacrifîce in the form of a meal. Eating the food is an essential part of the total sacrificial action; without the taking and eating, the memorial does not exist. Communion is not an optional appendage to the sacrifîce; it is an integral part of it. The meal is the sacrifîce; the sacrifîce is the meal.

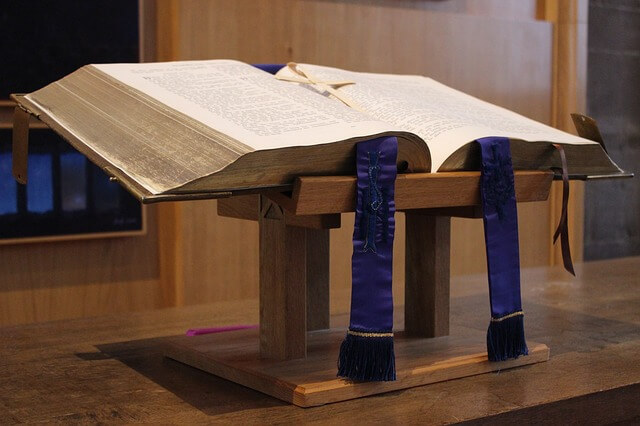

The oldest fairly complete description of the Mass as a formal liturgical service is that of the 2d century apologist St. Justin. Although Justin lived in Rome, the service he recorded is not simply a local liturgy, because this phenomenon had not yet evolved, but the form of the Eucharist used throughout the Roman Empire, both East and West. The ordinary Sunday Eucharist consisted of two parts: the Liturgy of the Word, as it is now called, and the Eucharistic Liturgy.

The Liturgy of the Word began with readings from both the Old and New Testament. Justin fails to mention the number of passages read, as well as whether psalmody was used. Most scholars agree, however, that there were three scriptural readings, the first two of which were ended by Psalms. Indeed, the use of Psalms probably predates Justin’s time. The “President of the Brethren” then delivered a homily based on the readings. A prayer in common, which corresponded to the modern “Prayer of the Faithful,” completed the first part of the service.

The Eucharistic Liturgy commenced with the kiss of peace. Since the kiss, which was actually an embrace, could be exchanged only by baptized Christians, the catechumens, or those not yet formally received into the church, had already left. Thus the kiss of peace symbolized the fellowship in Christ of the Christians who were about to reenact his sacrifîce. The bread and wine needed for the Eucharistic meal had been brought by the people and deposited with the deacons at the door of the housechurch.

The bread used then, and for many centuries following, was leavened bread baked in the form of small loaves by the women of the congregation. At this point in the service, the bread and wine were carried to the altar table where the bishop would reenact the words and actions of Christ at the Last Supper. When the offering was över, the president of the brethren said the Eucharistic Prayer, a prayer of praise, blessing, and thanksgiving, which was completely extempore. This prayer continued to be composed according to the president’s ability until the 4th century, when the traditional prayers were recorded and then became fixed. The Eucharistic Prayer ended with a doxology, and the people responded with “Amen.”

Communion followed immediately after the Prayer was completed. Although Justin does not describe the manner in which communion was received, later writers indicate that the people received the consecrated bread in their hands and communicated themselves; they then sipped the consecrated wine from the chalice held by one of the deacons.

The Development of Regional Rites.

In St. Justin’s time each church was allowed to arrange the details of the Mass in any manner it preferred, as long as the main elements were present: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. But the universal, fluid rite gradually gave place to standardized regional rites. This evolution occurred mainly because of the rapid growth of the church. Until the 4th century the bishop was the only chief celebrant of the Eucharist. The presbyters had been his concelebrants.

As Christianity spread, the bishops found it necessary to establish more churches. This multiplication of parishes required the bishops to delegate priests as the celebrants of the Eucharist on the local level. Unlike the bishop, however, the local priests did not compose the prayers of the Eucharistic service; rather they copied the prayers used in the cathedral church and recited these at their own services. The books into which the prayers were collected were called sacramentaries, the forerunners of the later missal and the modern sacramentary.

The changed conditions brought about by the Peace of the Church under Emperor Constantine also had farreaching effects upon the liturgy. The church buildings became larger, finer, and more elaborately decorated. The services naturally tended to keep pace with the architecture, and as the 4th century drew to a close the austere primitive service yielded to a more highly developed liturgy.

The great centers of Christian influence at Rome, Antioch, and Alexandria, as well as in southern France, developed certain elaborate liturgical practices that ali the churches in the surrounding regions imitated. By the end of the 4th century there were four majör rites, or liturgical families. Ali the liturgies of Christendom, whether Catholic, Orthodox, or Protestant, stem from these four parent rites: Antiochene, Alexandrian, Roman, or Gallican.

The Mass of the Roman Rite. The Roman Rite, the most widespread of ali, began as the local liturgy of the church of Rome. Originally austere, with little external ritual, it slowly absorbed something of the ceremonial color and pageantry of the imperial court. Although it stili remained less complex than the other rites, as the churchhouses were everywhere replaced by splendid basilicas, the services became longer and more involved. And whereas formerly there were no proper vestments as such, or speeial tableware, church vessels and vestments began to assume a distinctive ecclestiastical character.

Other changes of farreaching consequence occurred in the last part of the patristic period. Çeremonial developed, that is, entrance processıons, offertory processions, communion processions, and speeial chants to accompany the processions. The sehola, or speeial choir required to sing this complex music, soon began to sing the responses that once belonged exclusively to the people. A little later the loaves of leavened bread were replaced by small unleavened wafers, which effectively destroyed the symbolism of the shared loaf. Instead of placing the consecrated bread in the communicant’s hand so that he could communicate himself, the celebrant now placed the small wafer on the person’s tongue.

The position of the altar was also changed. It was pushed back until it was placed against the rear wall of the sanetuary. The celebrant no longer faced the people, but stood in front of the altar with his back toward them. There are several explanations for this change: the Roman Rite borrowed the custom of facing east, and therefore away from the people, from the Gallican Rites, which, in turn, had borrowed it from the East. Another explanation is that the custom of placing large shrines behind the altar made it impossible for the priest to stand there. Whatever the reason, this custom removed the people stili further from the altar and the sanetuary, heightened the air of mystery that surrounded the altar, and, inevitably, made the liturgy more remote and inaccessible. The distance between altar and nave represented the progressively widening gap between clergy and laity.

Although the Mass of the Roman Rite had originally been confîned to the city of Rome and its environs, it began to spread to the rest of Europe in the 6th and 7th centuries. St. Augustine of Canterbury brought the Roman Rite to the AngloSaxon missions of southem England in 596. A century later it infiltrated the churches of France. Early in the 9th century, by a decree of Charlemagne, the Roman Rite as modified by Alcuin was adopted in ali the churches of the realm.

Despite the fact that the Roman Rite had replaced the Gallican Rite almost universally, customs of the Gallican rites were transferred to the Roman liturgy. Many of its ceremonials and prayers are stili used in the Roman Rite. The procession on Palm Sunday and the use of incense, for example, are of Gallican origin. The Roman service books that were sent beyond the Alps returned greatly transformed. The Gallicanized books rapidly became the norm and Standard of worship in Rome itself, and by the end of the Middle Ages prevailed throughout western Europe.

The Decline of the Liturgy.

What had once been the corporate communal worship of the whole people of God had, by 1517, become an elaborate, formal ritual performed by specialists. The people no longer took a direct part in the rites; they assisted at them. While the clergy performed the official liturgy, the people filled in the time with the rosary and other private and individual devotions.

These things, good in themselves, were inadequate substitutes for the liturgy itself. Furthermore, the practice of communion, which is the heart and soul of liturgical participation, had so declined that the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 made it compulsory for the faithful to communicate at least once a year. Communion was the only real participation left to the average layman: he could not understand the service because it was recited in Latin; even if books had existed containing translations of the Latin, few laymen were able to read, supposing that they could afford to buy them» and the peoples’ participation in the chants had long ago ceased.

By the end of the Middle Ages the liturgy, as such, had ceased to be an effective force in the lives of the people. Although the Council of Trent was convoked in 1545 to effect reform in the church, it did not actually reform the liturgy. It suppressed some abuses and provided an editio typica, or standard for the liturgical books, but far more was needed. Because of the lack of knowledge of the liturgy at that time, it could hardly be restored. The Roman Rite was frozen into a rigid mold: ali the essential elements remained, but there was no savor, no warmth, and no vitality evident.

Liturgical Reform and Renewal.

Interest İn the nature of the liturgy was rekindled in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the 19th century, liturgical studies, along with a renewed appreciation of the Scriptures, were sparked by the fresh inquiry into the nature of the church itself. Thus the liturgy was again viewed as the act of the priestly church. Once this line of reasoning was established, it moved toward a natural conclusion: if the liturgy is the act of the church, then it is the act of the whole church, the people as well as the clergy, because the church is precisely “God’s holy people.” If it is the act of the people, the people should participate directly in the liturgy.

The decades before the 1960’s were, therefore, marked by extensive study of the whole idea of the liturgy, its general structure, and its component elements. Books, periodicals, and articles appeared, and conferences and lectures were given, in ali the modern European languages, as well as in Latin, examining the liturgy from every possible point of view—historical, pastoral, doctrinal, spiritual. From a study of what the liturgy was, the scholars progressed to a study of what the liturgy should be. Without this vast literary efîort the restoration of the liturgy would never have been seriously considered, let alone actually begun.

By his decree on frequent and daily communion in 1905, as well as by his encouragement of the people’s participation in the Mass, Pius X gave a great impetus to the liturgical renewal. But the credit for launching the modern liturgical movement belongs to a Belgian Benedictine, Dom Lambert Beauduin (18731960). The object of this liturgical movement was to make the faithful more conscious of the liturgy and especially of the Mass. The first step in this educational program was to make the vernacular missal available to the laity in small, inexpensive editions equipped with a detailed commentary on the liturgy. These missals, which were left in the churches, were probably the most effective means of making the faithful aware of the liturgy, and awakening in them a love for it.

As time progressed the faithful clearly realized that this was not enough; even with missal in hand the layman was stili not participating actively. The desire for greater participation found expression in the dialogue, or recited, Mass, which gained acceptance in some parts of Europe. By 1958 it was not only accepted but was highly recommended by the Instruction on Sacred Music and the Liturgy. The main obstacle, however, stili remained—the Latin language. More and more the leaders of the reform movement realized that the Mass could not become the genuine prayer of the people until at least the people’s parts were in their own language. This was not to be realized until Vatican II promulgated the Constitution on the Liturgy.

The Constitution on the Liturgy is the culmination of decades of scholarly inquiry. its purpose is to renew the liturgy. The liturgy, however, cannot be renewed if those who celebrate it are not themselves renewed. The real purpose of the Constitution, then, is to renew the church through a renewal of the liturgy. Thus the entire concern of the Constitution is pastoral: it is concerned with the life of the church and the spiritual growth of its members.

The Constitution goes to the root of the problem by providing for complete reform of the rites themselves. The guiding principle of liturgical celebration is no longer conformity to liturgical books, but intelligibility to the people: “in the revision of the liturgy the rites should be distinguished by a noble simplicity; they should be short, clear, and unencumbered by useless repetitions. They should be within the people’s powers of comprehension and normally should not require much explanation.”

The chief importance of the Constitution on the Liturgy is that it establishes the principle that the liturgy is the activity of the whole church, not just of a part of the church. It stresses the communal nature of the liturgy. Never again will the people be silent spectators of someone else’s activity. Instead they will be active participants in an activity that belongs to them.