Who was Ben Jonson? Explore the life and works of Ben Jonson, the influential English playwright and poet of the Renaissance era. Discover his captivating plays, satirical comedies, and timeless contributions to English literature.

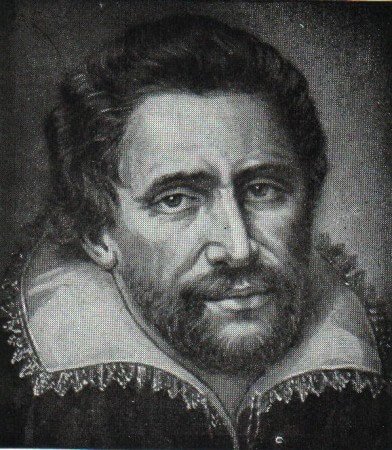

Ben Jonson; (in full Benjamin), English playwright and poet: b. in or near London, 1572, probably June 11; d. London, Aug. 6, 1637. Of Border descent, his father had lost his estate under Queen Mary, turned minister of the Gospel, and died a month before Ben’s birth; of his mother little is known except that she took as second husband a master bricklayer. The young Jonson lived in the neighborhood of Charing Cross and attended “a private school in St. Martin’s Church.”

He was then provided by an unidentified friend with means to attend Westminster where he studied under William Camden. About 1589 he was put into the craft of his stepfather, an occupation which he found far from his liking. Consequently he took arms as a volunteer in Flanders, challenged an enemy to single combat in the face of both camps, killed him, and stripped him of his arms. Returning to London, he threw in his lot with the theater, first as actor and later as prentice playwright. By 1595 he had married, and a year later the first of his three children, none of whom were to survive him, was born.

Jonson’s known literary career began when he finished a satiric comedy by Thomas Nash, The Isle of Dogs, presented in the summer of 1597. The play gave offense, and the actors including Jonson were arrested and imprisoned by order of the Privy Council; they were released in October, but this was not the last time Jonson brushed with authority. In the same year, Jonson was in the employ of Philip Henslowe. Plays for Henslowe, or others, included: perhaps the first version of A Tale of a Tub; The Case Is Altered, probably 1597-1598; and some unknown by name. In the fall of 1598, Francis Meres lists Jonson, surprisingly enough, among the writers best for tragedy.

The year 1598, indeed, was an important one for Jonson; it marked the real beginning of his success as a dramatist and almost brought it to an abrupt conclusion. In September his comedy, Every Man in His Humour, was performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Company; it was the first of his plays to receive signal applause and the first which he chose for preservation. A few days later he engaged in a duel with one of Henslowe’s actors, Gabriel Spencer, was wounded in the arm, but killed his opponent. Arrested and tried at the Old Bailey, he escaped with his life only by pleading benefit of clergy. Upon dismissal he was branded on the thumb as a felon, and his goods were confiscated. During his incarceration he became a Roman Catholic.

Despite his narrow escape, Jonson’s critical arrogance soon precipitated new quarrels. His Every Man Out of His Humour (1599), a “comical satire” for Shakespeare’s company, though not a success, made fun of the “fustian” diction of the poet-playwright, John Marston, who retorted in kind. Cynthia’s Revels (1600), Jonson’s mythological satire of court affectations for the Children of the Chapel, added Thomas Dekker to the comradeship of Marston, and Poetaster (1601), also for the Children, continued the assault.

Dekker’s hearty laughter, in his Satiromastix (1601), at a man who took himself too seriously, brought to a close the so-called “war of the theatres.” It is clear that the clash was temperamental and fanned by the rivalry between the various companies for which Jonson wrote. Jonson had collaborated with Dekker and others in 1599 on two tragedies now lost, for the Admiral’s Company. In 1602 he wrote a historical play and “additions,” also for Henslowe, to Thomas Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy, a play in which he had acted years before. Nevertheless, Poetaster offended many people who saw themselves or their professions ridiculed, and his Apologetical Dialogue was in itself offensive. In it Jonson announced that since his comedies had “proved so ominous,” he would try “If Tragoedie have a more kind aspect.”

Jonson’s vigorous contentiousness as well as his great artistic gifts brought him, however, staunch friends as well as enemies. Early in 1602 he was living with Sir Robert Townshend, and a bit later with Esme Stuart, lord of Aubigny and future duke of Lennox, whose hospitality he enjoyed for some years. Though his grave tragedy, Sejanus, produced by Shakespeare’s company in 1603, was rejected by audiences, the accession of James I brought new ones.

In August he provided an entertainment for the queen and the prince at Althorpe, and he and Dekker wrote the speeches for James’ formal entry into the city in March 1604; in May he assisted Sir William Cornwallis in entertaining royalty at Highgate; and The Masque of Blackness for the Christmas festivities of 1604-1605, on which he collaborated with Inigo Jones, was the first of a long series of court successes in the masque form, which he was to develop and dignify. About this time, too, he established himself at the Mermaid Tavern as the leading spirit of a convivial group of wits and writers which included Shakespeare and Francis Beaumont.

On the other hand, two events could well have proved disastrous. The earl of Northumberland had not taken well Jonson’s chastisement of one of his servants and summoned him before the Privy Council on the accusation of “poperie and treason.” Evidently Jonson’s friends interceded. In 1604 he was in trouble again. With Marston and George Chapman, Jonson collaborated on a comedy, Eastward Ho, which contained incidentally some satire on the Scots. It speaks well for Jonson that when his fellow authors were imprisoned, he voluntarily joined them. Despite the rumor that they should have “their ears cutt & noses,” Jonson and his collaborators, seconded again by powerful friends, escaped unscathed Indeed, in November of 1605, Jonson was even employed by the Privy Council in obtaining evidence about the Gunpowder Plot.

The next ten years were probably Jonson’s happiest and certainly the most fruitful and rewarding. His great comedy, Volpone, or The Fox, produced by the King’s Men in 1606, was so outstanding a success that it was presented also at Oxford and Cambridge. In the realm of courtly entertainment, Hymenaei (1605)was succeeded by Hue and Cry after Cupid

(1608), both for weddings; The Masque of Beauty (1608) and The Masque of Queens (1609). The last year saw too the laughable comedy, Epicoene, or the Silent Woman, for the Children at Whitefriars, and 1610, perhaps his greatest, The Alchemist, for the King’s Men. About this time Jonson returned to the Church of England.

Another attempt at tragedy for the King’s Men, Catiline (1611), proved a failure, but the vigorous comedy, Bartholomew Fair, produced by the Lady Elizabeth’s Company in 1614, was a brilliant success. Meanwhile the masques continued. In 1613, Jonson visited France, acting as tutor to the son of Sir Walter Raleigh. Already he had probably begun to plan the collection and publication of those writings which he thought worthy of posterity ; the Workes appeared in folio in 1616, a monument for which posterity is grateful, despite the contemporary laughter which greeted his self-assurance.

Jonson was now at the height of his fame, but except for the somewhat perfunctory The Devil Is an Ass (1616), he wrote nothing for the public stage for nine years. With many friends, noble and literary, with a pension from James and other incidental rewards, recognized by the two universities, Jonson was free to devote his time to various other pursuits, poetic, scholarly, and pleasurable. In 1618 he undertook a pedestrian expedition to Scotland, where he was entertained by many and notably by the poet, William Drummond of Hawthornden, who has preserved his conversation and many biographical details. Welcomed on his return by the king, holding high court in the Devil Tavern, formally inducted honorary master of arts by Oxford University as a man of distinguished learning in humane letters, he was widely recognized as the foremost literary figure in England.

The succeeding years, however, were not so bright. In 1623 his library was destroyed by fire and along with it much work projected or partially completed. Less than two years later King James was dead, and it became clear that Charles I preferred the type of court masque which put Inigo Jones’ spectacle over Jonson’s poetry. Jonson perforce returned to the stage, this time with another comedy, The Staple of Nezvs (1626), a success at Blackfriars and at court. It was at the same time the beginning of the decline of his powers.

For the first five winters of the new reign, Jonson was not invited to prepare masques for the court. His financial resources were embarrassed. In 1628 his huge bulk was stricken with paralysis, and his next play, The New Inn, written from a sickbed and performed early in 1629 by the King’s Company, was damned. Jonson’s pecuniary difficulties were somewhat relieved by his appointment as city chronologer, and later by gifts from Charles and an increase in his pension, but his call to join with Jones in masques at court in 1631 caused a quarrel with Jones which ended Jonson’s participation.

His Magnetic Lady (1632), presented by the King’s Men, was clearly not by the Jonson of old, and enemies sneered, Jones among them. Jonson retorted with a caricature of Jones in A Tale of a Tub (1633), a revision of a much earlier work, which was first censored and even then “not likte” at court.

Confined now to his bed in his house in Wesminster, Jonson was able to produce little more. He read prodigiously, made notes which were preserved in his Discoveries, devised a couple of masques for the duke of Newcastle, and wrote part of a pastoral play, The Sad Shepherd, never completed. His friends flocked around him, and there is evidence of a kind of restoration to the favor of the king. Nevertheless he was in debt when he died on Aug. 6, 1637. Three days later, attended by a great throng of admirers, he was buried in the Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey. A memorial volume, Jonsonus Viribus, appeared the following March, but the monument planned was doomed by the impending war. A square flagstone inscribed “O rare Ben Jonson,” at the request of a friend, has since disappeared.

The apparently paradoxical elements in Jonson’s character were united by the driving forces which determined his life and opinions. He was Latinist and duelist, Catholic and Protestant, a classicist of marked unrestraint, self-important but generous to those he loved and admired, serious in his convictions but free in jest and gullery. Yet in all he did there was a combinative vigor and honesty.

He did not suffer fools gladly, and he sometimes confused fools with those who disagreed with him or disliked his assertiveness. But there was nothing puny about Jonson. His reactions were as strong as his critical opinions, which he held to be valuable and demonstrable; if his pronouncements seemed Olympian, he had some reason to be confident. It is characteristic of him that though they disagreed and frequently clashed, he managed to work with Jones for years; that he could ridicule Marston and Dekker, and then shortly collaborate with them; that he could criticize Shakespeare, and yet

. . . confesse thy writings to be such,

As neither Man, nor Muse can praise too much.

The rounded character of Jonson’s genius made him scholar, critic, poet, masque writer, and dramatist—in short, a genuine man of letters. Some of his translations and studies burned with his library, but he left a translation of Horace’s Art of Poetry and an English Grammar. Thirty-six of his masques and entertainments remain to illustrate the nicety of his taste and the fertility of his invention; Jonson indeed brought the masque to its highest point of perfection. His nondramatic poetry, chiseled in its precision, now outspokenly direct, now lyrically graceful, is largely contained in The Epigrams, The Forest, and Underwoods.

But it was as critic and playwright that Jonson made his most distinguished contribution both to his own day and to the future. He was at once classicist, realist, and satirist. The Elizabethan drama which flowered in John Lyly and Robert Greene, in Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe, and in Shakespeare, had elements of all these tendencies, but remained essentially romantic in its exuberance, its variety, and its violation of the so-called classical rules. Jonson, critic before artist, was conscious of apparent formlessness and individual caprice, of incongruity both in aim and material. He insisted on the high dignity of literature, on the acceptance of classical precept and example, on standards and detailed workmanship. His textbooks were Aristotle and Horace; his method, the judicious adaptation of precedent to current needs.

In tragedy, Jonson strove for “truth of Argument, dignity of Persons, gravity and height of Elocution, fullness and frequency of Sentence.”

In comedy Jonson’s method was the development from the physiological theory of humours of a new satirical comedy. According to this theory, temperament and behavior were determined by the predominance of one or more of the bodily fluids. A proper mingling made a proper man; a disproportion determined his special bent or characteristics. A “humorous” man, then, is an unbalanced one and a subject for corrective satire. Jonson’s best comedies are all adaptations with various modifications of these ideas.

Not only do characters become types, at their best universal and allied to those of classical comedy though adapted to present observation, but supersede plot in importance; plot becomes the means for providing situations in which humours may be exhibited in action and dialogue. In Volpone, Epicoene, The Alchemist, and Bartholomezv Fair, Jonson shows man’s foibles with joyous comic resource, and these plays are among the finest achievements of English comedy.

Jonson’s masques have lost interest to any but professed specialists; his translations and scholarship have been superseded; only a few of his poems are preserved in anthologies, or read or sung today; his criticism is valuable, but has been absorbed into the great body of literary judgment and taste. Much of what he wrote was of his age and of a great age. But Jonson, the man of letters, remains in his comedies. They had enormous influence on the drama; they are studied in colleges and universities as examples of high comic art and brilliant dramaturgy; and they are frequently revived on both the amateur and the professional stage. They are the permanent heritage of the modern world from “rare Ben Jonson.”

mavi